The University of Chicago the Ethical Views of Michel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critical Inquiry As Virtuous Truth-Telling: Implications of Phronesis and Parrhesia ______

______________________________________________________________________________ Critical Inquiry as Virtuous Truth-Telling: Implications of Phronesis and Parrhesia ______________________________________________________________________________ Austin Pickup, Aurora University Abstract This article examines critical inquiry and truth-telling from the perspective of two comple- mentary theoretical frameworks. First, Aristotelian phronesis, or practical wisdom, offers a framework for truth that is oriented toward ethical deliberation while recognizing the contingency of practical application. Second, Foucauldian parrhesia calls for an engaged sense of truth-telling that requires risk from the inquirer while grounding truth in the com- plexity of human discourse. Taken together, phronesis and parrhesia orient inquirers to- ward intentional truth-telling practices that resist simplistic renderings of criticality and overly technical understandings of research. This article argues that truly critical inquiry must spring from the perspectives of phronesis and parrhesia, providing research projects that aim at virtuous truth-telling over technical veracity with the hope of contributing to ethical discourse and social praxis. Keywords: phronesis, praxis, parrhesia, critical inquiry, truth-telling Introduction The theme of this special issue considers the nature of critical inquiry, specifically methodological work that remains committed to explicit goals of social justice and the good. One of the central concerns of this issue is that critical studies have lost much of their meaning due to a proliferation of the term critical in educational scholarship. As noted in the introduction to this issue, much contemporary work in education research that claims to be critical may be so in name only, offering but methodological techniques to engage in critical work; techniques that are incapable of inter- vening in both the epistemological and ontological formations of normative practices in education. -

Digital Parrhesia 2.0: Moving Beyond Deceptive Communications Strategies in the Digital World François Allard-Huver, Nicholas Gilewicz

Digital Parrhesia 2.0: Moving beyond deceptive communications strategies in the digital world François Allard-Huver, Nicholas Gilewicz To cite this version: François Allard-Huver, Nicholas Gilewicz. Digital Parrhesia 2.0: Moving beyond deceptive communi- cations strategies in the digital world. Handbook of Research on Digital Media and Creative Tech- nologies, pp.404-416, 2015, 978-1-4666-8205-4. 10.4018/978-1-4666-8205-4.ch017. hal-02092103 HAL Id: hal-02092103 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02092103 Submitted on 7 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Digital Parrhesia 2.0: Moving beyond Deceptive Communications Strategies in the Digital World François Allard-Huver Sorbonne University, France Nicholas Gilewicz University of Pennsylvania, USA ABSTRACT Deceptive communications strategies are further problematized in digital space. Because digitally mediated communication easily accommodates pseudonymous and anonymous speech, digital ethos depends upon finding the proper balance between the ability to create pseudonymous and anonymous online presences and the public need for transparency in public speech. Analyzing such content requires analyzing media forms and the honesty of speakers themselves. This chapter applies Michel Foucault’s articulation of parrhesia—the ability to speak freely and the concomitant public duties it requires of speakers—to digital communication. -

A Case of Parrhesia: Courage in Discourse and Its Effects

Original Article A CASE OF PARRHESIA: COURAGE IN DISCOURSE AND ITS EFFECTS Thiago Barbosa SOARES* ▪ ABSTRACT: This article aims to analyze the meanings of parrhesia and its effects in a statement by a Brazilian federal representative, that breaks with hegemonic discourse. More precisely, we describe and interpret how the production and emergence of parrhesia functions to configure meanings in a statement constituted and developed within the vote regarding the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff’s mandate in 2016, delivered by Jean Wyllys. In this way, considering the postulate of Discourse Analysis, developed by Pêcheux, in which subject and meaning are constructed simultaneously in the historical movement, we hold that parrhesia, as Foucault observes it in his final works, produces, simultaneously, certain meanings and subjects circulating in the social space. Given this conceptual framework, we employ the theoretical and methodological tools of Discourse Analysis to investigate how truth-telling is constructed and what its effects are on the treadmill of resistance against discursive hegemony. ▪ KEYWORDS: discourse analysis; parrhesia; Jean Wyllys. Introduction A ‘discourse’ is not an infrastructure; nor is it another word for ‘ideology’. In fact, it is, rather, the opposite, despite what is often claimed either in writing or by word of mouth. (VEYNE, 2008, p.28) Paul Veyne is right in saying what discourse is not, in order to dispel certain existing interpretations about discourse. Likewise, eschewing generic readings of discourse is desirable and even necessary in the scope of our object of investigation, since the exercise of parrhesia - which “implies speech equality, the right to speak”, that is, isegory -, as understood by Michel Foucault, it is more than truth-telling, it is an ethical act whose implication is the conjuration of the effects of the discourse. -

The Meaning of Hermeneutics and Symbolism

PARRHESIA WWW.PARRHESIAJOURNAL.ORG ISSUE 1 201 INTRODUCTION The meaning of hermeneutics is not something exclusive to hermeneutics; it is not something the hermeneutical enterprise dominates, masters, or even manages. Rather, hermeneutics must understand itself as an activity at the behest of meaning, which it is incapable to exhaust or contain. The meaning of hermeneutics therefore does not belong to hermeneutics, but, on the contrary, hermeneutics belongs to meaning. Its meaning is that which, in one way or another, always pursues and persecutes human beings, who, as interpreting or symbolic animals, is thus limited to a realization of what humans already do—whether explicitly or implicitly; actively or passively—in their individual and collective lives: a search for meaning.1 Now, philo-sophers love and pursue a forever-elusive wisdom, even though, according to Plato, just by the fact of pursuing it, we are guided by it, at least with Socrates and Nicolas of Cusa, to the point of docta ignorantia. In parallel with this and likewise in the search for meaning, be it existential or hermeneutical, meaning. Rather, its evident result is meaninglessness, since, without the felt disquietude of the latter there would not have been any search whatsoever. This search may even lead us to the understanding that human meaning consists in assuming and accepting ontico-literal, effective, patent meaninglessness, so as to thrust it open to ontologico-symbolic, affective, latent meaning. Resignation appears here as the possibility of re- signation [re-signación] (Vattimo) and of as-signment [a-signación], given that the resigned acceptance of the absence of absolute, powerful, and explicit meaning makes possible the acknowledgement of the humanness of our interpretations as such and the assignment to life and the universe of a plurality of linguistic, symbolic, relative or relational, meanings. -

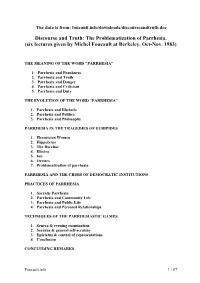

Discourse and Truth: the Problematization of Parrhesia. (Six Lectures Given by Michel Foucault at Berkeley, Oct-Nov

The data is from: foucault.info/downloads/discourseandtruth.doc Discourse and Truth: The Problematization of Parrhesia. (six lectures given by Michel Foucault at Berkeley, Oct-Nov. 1983) THE MEANING OF THE WORD "PARRHESIA" 1. Parrhesia and Frankness 2. Parrhesia and Truth 3. Parrhesia and Danger 4. Parrhesia and Criticism 5. Parrhesia and Duty THE EVOLUTION OF THE WORD “PARRHESIA” 1. Parrhesia and Rhetoric 2. Parrhesia and Politics 3. Parrhesia and Philosophy PARRHESIA IN THE TRAGEDIES OF EURIPIDES 1. Phoenician Women 2. Hippolytus 3. The Bacchae 4. Electra 5. Ion 6. Orestes 7. Problematization of parrhesia PARRHESIA AND THE CRISIS OF DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS PRACTICES OF PARRHESIA 1. Socratic Parrhesia 2. Parrhesia and Community Life 3. Parrhesia and Public Life 4. Parrhesia and Personal Relationships TECHNIQUES OF THE PARRHESIASTIC GAMES 1. Seneca & evening examination 2. Serenus & general self-scrutiny 3. Epictetus & control of representations 4. Conclusion CONCLUDING REMARKS Foucault.info 1 / 67 The Meaning of the Word " Parrhesia " The word "parrhesia" [παρρησία] appears for the first time in Greek literature in Euripides [c.484-407 BC], and occurs throughout the ancient Greek world of letters from the end of the Fifth Century BC. But it can also still be found in the patristic texts written at the end of the Fourth and during the Fifth Century AD -dozens of times, for instance, in Jean Chrisostome [AD 345-407] . There are three forms of the word : the nominal form " parrhesia " ; the verb form "parrhesiazomai" [παρρησιάζοµαι]; and there is also the word "parrhesiastes"[παρρησιαστής] --which is not very frequent and cannot be found in the Classical texts. -

Political Rhetoric: the Modern Parrhesia

The Catalyst Volume 4 | Issue 1 Article 5 2017 Political Rhetoric: The oM dern Parrhesia Jessica Townsend University of Southern Mississippi, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://aquila.usm.edu/southernmisscatalyst Part of the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Townsend, Jessica (2017) "Political Rhetoric: The odeM rn Parrhesia," The Catalyst: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. DOI: 10.18785/cat.0401.05 Available at: http://aquila.usm.edu/southernmisscatalyst/vol4/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC talyst by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Catalyst Volume 4 | Issue 1 | Article 5 2017 Political Rhetoric: The Modern Parrhesia Jessica Townsend The French philosopher Michel Foucault is substantial manner by speaking this truth, use best known among academics as a theorizer this truth to criticize the audience, and feel a of human nature and social relationships. sense of duty to speak this criticism (Foucault Although his areas of expertise did not 1983). The risk that goes along with parrhesia encompass politics, which he attempted typically includes risk of life, punishment, or to avoid altogether in his writings, many significant loss of social standing. Because of of his philosophical ideas have been re- this, the truth-teller must be subordinate to examined inside a political context. One of the audience. However, the one speaking with his major theories, the idea of free speech parrhesia, the parrhesiastes, also must be free known as parrhesia, has made its way to the to speak the truth freely of his own accord; foreground of scrutiny by political theorists meaning that he must also not be a slave or as well as an internationally-acclaimed non-citizen, in the case of ancient Greece expert in rhetoric and professor by the name (Foucault 1983). -

Examined Lives Excerpt Intro

introduction Of all those who start out on philosophyÐ not those who take it up for the sake of getting educated when they are young and then drop it, but those who linger in it for a longer timeÐ most become quite queer, not to say completely vicious; while the ones who seem perfectly decent . become useless. —, Republic (487c± d) Q Excerpted from EXAMINED LIVES: From Socrates to Nietzsche by James Miller. Published in January 2011 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Copyright © 2011 by James Miller. All rights reserved. 042-44795_ch01_5P.indd 3 10/29/10 11:17 PM Excerpted from EXAMINED LIVES: From Socrates to Nietzsche by James Miller. Published in January 2011 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Copyright © 2011 by James Miller. All rights reserved. 042-44795_ch01_5P.indd 4 10/29/10 11:17 PM nce upon a time, phi los o phers were ! gures of wonder. " ey o were sometimes objects of derision and the butt of jokes, but they were more o# en a source of shared inspiration, o$ ering, through words and deeds, models of wisdom, patterns of conduct, and, for those who took them seriously, examples to be emulated. Stories about the great phi los o phers long played a formative role in the culture of the W est. For Roman writers such as C icero, Seneca, and M arcus A urelius, one way to mea sure spiritual progress was to compare one's conduct with that of Socrates, whom they all considered a paragon of perfect virtue. Sixteen hundred years later, John Stuart M ill (1806± 1873) simi- larly learned classical G reek at a tender age in order to read the Socratic ªM emorabiliaº of X enophon (fourth century %.&.) and selected Lives of the Em inent Phi los o phers, as retold by D iogenes Laertius, a G reek fol- lower of Epicurus who is thought to have lived in the third century .*. -

![European Journal of American Studies, 10-3 | 2015, « Special Double Issue: the City » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 31 Décembre 2015, Consulté Le 08 Juillet 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8943/european-journal-of-american-studies-10-3-2015-%C2%AB-special-double-issue-the-city-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-31-d%C3%A9cembre-2015-consult%C3%A9-le-08-juillet-2021-2608943.webp)

European Journal of American Studies, 10-3 | 2015, « Special Double Issue: the City » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 31 Décembre 2015, Consulté Le 08 Juillet 2021

European journal of American studies 10-3 | 2015 Special Double Issue: The City Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/11186 DOI : 10.4000/ejas.11186 ISSN : 1991-9336 Éditeur European Association for American Studies Référence électronique European journal of American studies, 10-3 | 2015, « Special Double Issue: The City » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 31 décembre 2015, consulté le 08 juillet 2021. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/ 11186 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.11186 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 8 juillet 2021. Creative Commons License 1 SOMMAIRE PART ONE Spatial Justice and the Right to the City: Conflicts around Access to Public Urban Space Introduction Aneta Dybska et Sandrine Baudry Urban Discourses in the Making: American and European Contexts Where the War on Poverty and Black Power Meet: A Right to the City Perspective on American Urban Politics in the 1960s Aneta Dybska Who Has the Right to the Post-Socialist City? Writing Poland as the Other of Marxist Geographical Materialism Kamil Rusiłowicz Segregation or Assimilation: Dutch Government Research on Ethnic Minorities in Dutch Cities and its American Frames of Reference Ruud Janssens Public Art: Transnational Connections “The cornerstone is laid”: Italian American Memorial Building in New York City and Immigrants’ Right to the City at the Turn of the Twentieth Century Bénédicte Deschamps Performing the Return of the Repressed: Krzysztof Wodiczko’s Artistic Interventions in New York City's Public Space Justyna Wierzchowska -

Sergei Prozorov Foucault's Affirmative Biopolitics: Cynic Parrhesia and The

Sergei Prozorov Foucault’s Affirmative Biopolitics: Cynic Parrhesia and the Biopower of the Powerless Introduction In History of Sexuality I and Foucault’s other works of the period, the theme of affirmative biopolitics was never addressed in an explicit manner, aside from a brief and still somewhat enigmatic reference to ‘bodies and pleasures’ that presumably pose an alternative to the biopolitics defined in terms of desire and sexuality.1 Of course, Foucault was notoriously evasive when it came to elucidating alternatives to the apparatuses of power and knowledge that he reconstituted, unwilling to subject them to a normative critique but content with showing how they historically emerged and how they can always be undone, if one so prefers.2 We should also recall that the theme of biopolitics was only Foucault’s explicit concern during a relatively brief period of 1975-1977, after which his research shifted to the problematics of, respectively, governmentality, liberalism, confession and the techniques of the self.3 Yet, despite the brevity of Foucault’s explicit concern with biopolitics, rethinking biopower in the affirmative key remained an important concern of his final work. In this article we shall argue that Foucault’s work on parrhesia, particularly the lectures on Cynicism in his final course at the Collège de France, elucidates a version of biopolitics that does not negate ‘mere life’ in the name of a privileged form of ‘true life’ but rather relocates truth to the domain of life itself. Moreover, for Foucault Cynic practices of truth-telling were not an antiquated curiosity of 1 little relevance to our contemporary experience. -

Foucault.Info 1 / 66 Discourse and Truth

Discourse and Truth: The Problematization of Parrhesia. (six lectures given by Michel Foucault at Berkeley, Oct-Nov. 1983) THE MEANING OF THE WORD "PARRHESIA" 1. Parrhesia and Frankness 2. Parrhesia and Truth 3. Parrhesia and Danger 4. Parrhesia and Criticism 5. Parrhesia and Duty THE EVOLUTION OF THE WORD “PARRHESIA” 1. Parrhesia and Rhetoric 2. Parrhesia and Politics 3. Parrhesia and Philosophy PARRHESIA IN THE TRAGEDIES OF EURIPIDES 1. Phoenician Women 2. Hippolytus 3. The Bacchae 4. Electra 5. Ion 6. Orestes 7. Problematization of parrhesia PARRHESIA AND THE CRISIS OF DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS PRACTICES OF PARRHESIA 1. Socratic Parrhesia 2. Parrhesia and Community Life 3. Parrhesia and Public Life 4. Parrhesia and Personal Relationships TECHNIQUES OF THE PARRHESIASTIC GAMES 1. Seneca & evening examination 2. Serenus & general self-scrutiny 3. Epictetus & control of representations 4. Conclusion CONCLUDING REMARKS Foucault.info 1 / 66 The Meaning of the Word " Parrhesia " The word "parrhesia" [παρρησία] appears for the first time in Greek literature in Euripides [c.484-407 BC], and occurs throughout the ancient Greek world of letters from the end of the Fifth Century BC. But it can also still be found in the patristic texts written at the end of the Fourth and during the Fifth Century AD -dozens of times, for instance, in Jean Chrisostome [AD 345-407] . There are three forms of the word : the nominal form " parrhesia " ; the verb form "parrhesiazomai" [παρρησιάζοµαι]; and there is also the word "parrhesiastes"[παρρησιαστής] --which is not very frequent and cannot be found in the Classical texts. Rather, you find it only in the Greco-Roman period -in Plutarch and Lucian, for example. -

A Question of Two Truths? Remarks on Parrhesia and the 'Political

PARRHESIA NUMBER 2 • 2007 • 89–108 A QUESTION OF TWO TRUTHS? REMARKS ON PARRHESIA AND THE ‘POLITICAL-PHILOSOPHICAL’ DIFFERENCE Matthew Sharpe Where a community has embarked upon organized lying on principle, and not only with respect to particulars, can truthfulness as such, unsupported by the distorting forces of power and opinion, become a political factor of the first order. Where everybody lies about everything of importance the truthteller, whether he knows it or not, has begun to act. Hannah Arendt, ‘Truth and Politics’ In what were to be the final two lecture series of his life, French philosopher Michel Foucault1 turned his attention to the classical Greeks’ notion[s] of parrhesia: literally, ‘all-telling’, but as we shall see momentarily, something much closer to ‘truthfulness’ or even ‘probity’.2 Mu ch of Foucault’s career can be read as a series of inquiries into that most dizzying of Nietzschean questions: namely, ‘what really is it in us that wants ‘the truth’ … why not rather untruth?’3 Yet Foucault’s last lectures represent a significant development, and arguably a reflective ‘re-visioning’ of, his famous earlier inquiries into the politics of truth. Foucault’s genealogical inquiries of the early 1970s had traced the emergence (Enstellung)4 of the ‘true discourses’ of the modern human sciences from the ignoble milieus of the early modern prisons, barracks, schools and hospitals.5 The inquiries that make up the second two volumes of History of Sexuality analyze classical, Roman, and Christian conceptions of ethical self-formation: -

Eugene Debs and the Politics of Parrhesia James P

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2015 Eugene Debs and the Politics of Parrhesia James P. Flynn University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Flynn, J. P.(2015). Eugene Debs and the Politics of Parrhesia. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/ 3113 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EUGENE DEBS AND THE POLITICS OF PARRHESIA by James Patrick Flynn Bachelor of Arts Coker College, 2011 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: Pat Gehrke, Director of Thesis Gina Ercolini, Reader Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by James Patrick Flynn, 2015 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION For Kyria iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I first became acquainted with the concept of parrhesia while reading for Pat Gehrke‟s Classical Rhetoric graduate seminar. It appealed to me, and I wrote on parrhesia twice before this thesis. So, first, I am deeply indebted to Prof. Gehrke for introducing me to the concept, providing feedback on my previous seminar papers on parrhesia, and for lending his time to direct this thesis. I am also very grateful to Gina Ercolini for donating her time and energy to be a reader of this thesis.