Doll Paper: Reinvigorating the Post-Traumatic Female Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

[FIR 15.1–2 (2020) 204–205] Fieldwork in Religion (print) ISSN 1743–0615 https://doi.org/10.1558/firn.18365 Fieldwork in Religion (online) ISSN 1743–0623 BOOK REVIEW Calhoun, Scott (ed.) 2018. U2 and the Religious Impulse. London: Bloomsbury. xvi + 236 pp. ISBN: 9781501332395 £90.00 (hbk); ISBN: 9780567690210 £28.99 (pbk); ISBN: 9781350032552 £26.09 (e-book). Reviewed by: Barbara Pemberton, Ouachita Baptist University, AR, USA [email protected] Keywords: Irish rock; Christianity; U2; popular music; religion and media; popular cul- ture; musicology. U2 and the Religious Impulse, edited by Scott Calhoun, Professor of English at Cedarville Uni- versity, USA, is a collection of multidisciplinary essays considering the Irish rock band U2 and the enduring spiritual influence it has on fans. The aim of this book is to address new questions: “why the religious impulse in fans is so satisfyingly met by U2 … and why a broader group of religiously inclined fans are interested in U2” (p. 6). Calhoun has gath- ered an impressive group of scholars from a variety of fields including literature, theol- ogy, music, ethics, history, and political science, all providing excellent, thought-provoking essays. While all of the contributors share an interest in popular culture, several profess life- long U2 fandom. Since its formation by four musicians in 1976, U2 has been writing and giving landmark performances around the world, including the highest grossing concert ever—the 360° Tour. These critically acclaimed and immensely popular artists are unapologetically guided by their Christian faith, and their lyrics display a spiritual depth far beyond what may usu- ally be expected from rock music. -

A Study of Surrender in the Process of Transformation for Recovering Alcoholics

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1988 A study of surrender in the process of transformation for recovering alcoholics. Jane Marie Hart University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Hart, Jane Marie, "A study of surrender in the process of transformation for recovering alcoholics." (1988). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4648. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4648 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 3iEDbb DE^a osDa a FIVE COLLEGE DEPOSITORY A STUDY OF SURRENDER IN THE PROCESS OF TRANSFORMATION FOR RECOVERING ALCOHOLICS A Dissertation Presented by JANE MARIE HART Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION September 1988 School of Education A STUDY OF SURRENDER IN THE PROCESS OF TRANSFORMATION FOR RECOVERING ALCOHOLICS A Dissertation Presented by JANE MARIE HART Approved as to style and content by: UA/ OA djahn W. Wideman, Chairman of Committee Moma. Maurianne Adams, Member ren Schumacher Marilyn H^ring-Hidore, School of Education 0 Copyright by Jane Marie Hart 1988 All Rights Reserved This dissertation is dedicated to the higher power within the hearts of all those who suffer with addictive attachments. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Jack Wideman continually generated the fuel which propelled this study and so many of the insights gained. -

Surrender: an Alchemical Act in Personal Transformation Moze, Mary Beth G

Journal of Conscious Evolution Volume 3 Article 10 Issue 3 Issue 03/2007 May 2018 Surrender: An Alchemical Act in Personal Transformation Moze, Mary Beth G. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, Cognition and Perception Commons, Cognitive Psychology Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons, Social Psychology Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Sociology of Religion Commons, and the Transpersonal Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Moze, Mary Beth G. (2018) "Surrender: An Alchemical Act in Personal Transformation," Journal of Conscious Evolution: Vol. 3 : Iss. 3 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal/vol3/iss3/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Conscious Evolution by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : Surrender: An Alchemical Act in Personal Transformation Surrender: An Alchemical Act in Personal Transformation Mary Beth G. Moze1 Abstract This article is the result of inquiring about human resistance to change. Specifically, it focuses on the act of surrender which engages, rather than avoids, the process of transformation. Due to the relatively sparse amount of literature on the subject of surrender, additional literature which parallels and compliments the subject is creatively woven in. The author comfortably injects criticism and interpretation of the literature and intermittently offers suggestions for further research efforts. -

Surrendering to Jesus”

Season 1, Episode 2: “Surrendering to Jesus” Hey there, friends! We are going to continue something we started last week and that is the whole theme of telling our stories… today, with a little bit of an emphasis on surrender. I'm going to continue telling you part of my story in hopes that you can see how surrender was a big part of how I came to meet my husband and marry my husband and come into the ministry that I have today. So if you didn't listen to last week's episode, go back and do that and it'll kinda catch you up to speed. But I'm going to start out by sharing with you some of what I was going through before I met my husband, John, but after I had that big turning point in my life where I really started to fall in love with Jesus. I told you last week that I was involved in Bible study and I was really, really loving studying God's word and knowing him through his word and that's where I fell in love with him– it was just in his word. And as I was studying with this group across town at another church, I just kept thinking, Wow, we need to do this at my church! The women in my church need Bible study. (We did not have a formal Bible study in my church at that time.) So I went to talk to my friend, Happy, that I mentioned to you last week. -

Bernard Grindrod the SINGAPORE DEBACLE

Bernard Grindrod THE SINGAPORE DEBACLE – by Bernard Grindrod The moment of surrender was tense in the humid climate and low clouds over Singapore on that afternoon of Sunday, the fifteenth. It was February 1942. Lieutenant General Sir Arthur E. Percival, together with a few carefully selected senior staff officers, dismounted on Bukit Timah Road near the Ford Factory and walked across no man’s land to a hastily erected table on which a single document lay. There were British Officers carrying the Union Jack and the white flag. They reached the table and waited ---- a humiliating wait before Yamashita appeared and spoke. Cyril Wild translated as best he could with his limited knowledge of Japanese. They were already over an hour late for the appointment set up the previous day for four thirty and the Japanese General was angry. He spoke directly to Percival ignoring his own translator: Yamashita: “I wish your replies to be brief and to the point. I will listen only to unconditional surrender. Have you captured any Japanese soldiers?” Percival: “None”. Yamashita: “What about Japanese prisoners?” Percival: “All who have been interned have been sent to India. Their lives are fully protected.” Yamashita: “I want to hear whether you wish to surrender.” Percival: “Will you give me until tomorrow?” Yamashita: “I cannot wait.” Percival: “Give me five hours.” Yamashita: “Then we will continue to attack meanwhile.” General Percival remained silent but General Yamashita insisted on an answer and Percival finally replied, “Yes!” In this single word, his lateness, his inability to negotiate with strength knowing full well from current intelligence the Japanese were short of ammunition and outnumbered three to one, and his inability to make decisions painted the true picture of why Singapore surrendered. -

Persuasions of the Wild Writing the Moment a Phenomenology

PERSUASIONS OF THE WILD WRITING THE MOMENT A PHENOMENOLOGY Jana Milloy Bachelor of Fine Arts, Simon Fraser University, 1994 Master of Arts, Simon Fraser University, 2004 DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Faculty of Education O Jana Milloy 2007 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY 2007 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Jana Milloy Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Research Project: Persuasions of the Wild Writing the Moment A Phenomenology Examining Committee: Chair: Lynn Fels, Assistant Professor Stephen Smith, Associate Professor Senior Supervisor Celeste Snowber, Associate Professor Charles Bingham, Assistant Professor Dr. Stuart Richmond, Professor, Faculty of Education InternalIExternal Examiner Dr. Carl Leggo, Professor, Faculty of Education, UBC External Examiner Date: September 27,2007 SIMON FIIASEII UNIVERSITY Ll BRARY Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the "Institutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/l892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

MTO 17.3: Endrinal, Defining the Interverse

Volume 17, Number 3, October 2011 Copyright © 2011 Society for Music Theory Burning Bridges: Defining the Interverse in the Music of U2 Christopher Endrinal NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.11.17.3/mto.11.17.3.endrinal.php KEYWORDS: interverse, bridge, popular music, form, U2, Bono, The Edge, Adam Clayton, Larry Mullen Jr., introduction, verse, chorus, refrain, interlude, transition, conclusion ABSTRACT: Popular music analysis, particularly pop-rock analysis, presents several challenges. Despite the repetition and seeming simplicity of the harmonic progressions in many pop-rock songs, analyzing their form can be difficult. One of these difficulties lies in the terminology used to describe the sections within a song. Specifically, the term “bridge” is troublesome because frequently it does not adequately describe the function of the section it represents. Using the music of Irish group U2, this paper defines and illustrates the “interverse,” a new term for the section traditionally called a “bridge” in pop-rock music, one that more accurately describes how the section relates to immediately preceding and succeeding material, as well as how it functions within the song as a whole. In addition to introducing new terminology, this paper also defines, illustrates, and distinguishes among the traditional sections of a pop-rock song, namely the introduction, verse, chorus, refrain, interlude, transition, and conclusion. Received February 2011 [1] The word “bridge” suggests connecting or transitional function, as in the statement “bridging the gap between point A and point B.” A physical bridge links two otherwise separate entities. -

The Nine Principles Commitment

THE NINE PRINCIPLES COMMITMENT LESSON #6 – COMMITMENT – A RIGHT to some INPUT but NO QUESTION about the FINAL RESULT. (As a RESULT of practicing FELLOWSHIP, developing a BOND, expressing LOVE, relating in TRUTH and creating a level of TRUST – We HAVE A RIGHT to some INPUT in EACH OTHERS lives but NO QUESTION about the FINAL RESULT . However, after I MAKE that INPUT you DO NOT HAVE TO ACCEPT that INPUT and you WILL NOT be THROUGH with ME because I MAKE AN INPUT and NEITHER WILL I be THROUGH with YOU for NOT ACCEPTING the input. There is NO QUESTION about the FINAL RESULT . We will STILL be BROTHER and SISTER. SCRIPTURAL FOUNDATIONS: ACTS 17:28 MATTHEW 5:6 II CORINTHIANS 5:17-19 JOHN 21:15-17 MATTHEW 4:4 MATTHEW 18:15-17 PSALMS 119:105 ROMANS 8:37-38 THE MEANING OF COMMITMENT The experience of REAL COMMITMENT INVOLVES GOING BEYOND the extension of ONE’S LIMITS to a SOURCE OUTSIDE of ourselves that GIVES LIFE . A simple dramatic ILLUSTRATION is found IN NATURE that I have often cited. It ILLUSTRATES the DOGGED DETERMINATION and IRREPRESSIBLE URGE and DRIVE of COMMITMENT characteristic of ALL LIFE . When UNION TEMPLE owned APARTMENTS called WAYNE TERRACE we had a persistent PLUMBING PROBLEM in all 51 units where SEWAGE/WATER would BACK UP in apartments. To NO AVAIL many “CERTIFIED” professional PLUMBERS were CALLED IN at great expense to SOLVE the problem, but COULD NOT . Finally a “JACKLEG” PLUMBER came out and DIAGNOSED the problem in a very SHORT TIME . -

The Semi (03-30-2009)

Fuller Theological Seminary Digital Commons @ Fuller The SEMI (2001-2010) Fuller Seminary Publications 3-30-2009 The Semi (03-30-2009) Fuller Theological Seminary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fuller.edu/fts-semi-6 Recommended Citation Fuller Theological Seminary, "The Semi (03-30-2009)" (2009). The SEMI (2001-2010). 278. https://digitalcommons.fuller.edu/fts-semi-6/278 This Periodical is brought to you for free and open access by the Fuller Seminary Publications at Digital Commons @ Fuller. It has been accepted for inclusion in The SEMI (2001-2010) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Fuller. For more information, please contact [email protected]. the »PRING 1 • MARCH 30,2009 CONNECTING THE CAMPUS • CREATING DIALOGUE P e r s o n a l R e f l e c t io n b y D a n n ie l l e E. C a r r Or, worse, has that thought ever given rise to an action This man and I were going to the same floor, and that left you feeling rotten inside? Yes? Welcome to my within 30 seconds of sitting down, I realized we were des club! No? I would love the opportunity to sit at your feet, tined for the same room as well. He got there after me because I did something terrible the other day. because the elevator is a slow one. I watched as he walked Upon approaching an elevator, I scrutinized the line by, ignorant (I hope) of what just transpired, and I felt so up of people waiting. -

Via Positiva 2021: Dancing with the Divine

Via Positiva – Summer 2021 Dancing with the Divine Albert Einstein said, “The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and all science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead: his eyes are closed.” I would add it is the source of all true faith. The awe we feel in the face of mystery is the beginning of faith and this awe is at the heart of the Via Positiva. On our website, we say about this Via: “During these months, we discover beauty and awe in each other, in ourselves, and in the fascinating world around us.” Sometimes discovering the beautiful in ourselves or the people whose paths we cross or the world around us is easy: the moment of kindness, the perfect sunset. Other times, not so much: the brutal storm, the pointed blame, the dark regret. The call of the Positiva is to dance with it all. To find God at the center of it all. To play in the mystery and beauty and awe. Friedrich Nietzsche said, “Those who were seen dancing were thought to be insane by those who could not hear the music.” Let the insanity begin! June 20 – Dancing with the Light (Summer Solstice) Then God said, “Let there be light”; and there was light. ~ Gen. 1:1-4 I am happy even before I have a reason. I am full of Light even before the sky can greet the sun or the moon. -

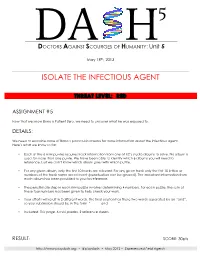

Isolate the Infectious Agent

! DOCTORS AGAINST SCOURGES OF HUMANITY: Unit 5 May 18th, 2013 ISOLATE THE INFECTIOUS AGENT ! ! ASSIGNMENT #5 ! Now that we know Bono is Patient Zero, we need to uncover what he was exposed to. ! DETAILS: ! We need to examine some of Bono’s past musical works for more information about the infectious agent. Here’s what we know so far: • Each of the 6 mini puzzles requires track information from one of U2’s studio albums to solve. No album is used for more than one puzzle. We have been able to identify which 6 albums you will need to reference, but we don’t know which album goes with which puzzle. ! • For any given album, only the first 10 tracks are relevant. For any given track only the first 10 letters or numbers of the track name are relevant (punctuation can be ignored). The important information from each album has been provided to you for reference. ! • The penultimate step in each mini puzzle involves determining 4 numbers. For each puzzle, the sum of these four numbers has been given to help check your work. • Your efforts will result in 2 different words. The final solution has these two words separated by an “and”, so your submission should be in the form “______ and ______” ! • Included: This page. 6 mini puzzles. 2 reference sheets. ! ! RESULT:!! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!SCORE: 30pts http://www.playdash.org • @playdash • May 2013 • Experienced Field Agents DASH5 — 5. ISOLATE INFECTIOUS AGENT ! VO1C1A1L C2O2MA2S ! ! ! Track! + ) ! ! Index! ) + ! ! Track!+ ! ! Index! )! ! Expected(Sum:(25( ! Tip:(Indexing(means(counting(in(a(certain(number(of( characters(from(the(start(of(a(word(or(phrase.( http://www.playdash.org • @playdash • May 2013 • Experienced Field Agents DASH5 — 5. -

Liturgical Offerings for High Holy Day Services Rosh Hashanah Morning 2020 – 5781

Liturgical Offerings for High Holy Day Services Rosh Hashanah Morning 2020 – 5781 Creative Offerings for High Holy Day Services 2020 – 5781 Rosh Hashana: A Morning Service These offerings are designed to provide a unique experience for our High Holy Day worship during this uniquely challenging moment. Intended for use for remote services using Zoom or another platform, they are limited to 90 minutes in length. We have not included sermons, divrei Torah, or any scriptural readings, assuming that different communities will want to add those at different points and to different degrees. Though these services are designed to be used as a whole and are inclusive of the liturgy we recommend, we are also providing them in a format that will allow borrowing, excerpting and use alongside a Mahzor or within services you are designing for your community. Recordings and music for many of the song options are available on Reconstructing Judaism’s website here With prayers of gratitude to the Source of Creativity and with the sincere desire that these be of use at this challenging moment. Crafted by a committee of Reconstructionist Rabbis Rabbi Michael Strassfeld, Chair, Rabbi Tamara Cohen, Rabbi Rachel Hersh, Rabbi Joshua Lesser, Rabbi Katie Mizrachi, Rabbi Ora Nitkin-Kanner, and Rabbi Jeremy Schwartz Executive Editor Rabbi Elyse Wechterman Produced by the Reconstructionist Rabbinical Association All Hebrew prayers, transliteration and translation (unless otherwise noted) are used, with permission, from Kol Haneshemah: Mahzor Leyamim Nora’im: Prayerbook for the Days of Awe Copyright The Reconstructionist Press, Wyncote, PA 2014 Works from external sources are used with the permission of the author or copyright holder for this purpose.