A Study of Surrender in the Process of Transformation for Recovering Alcoholics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ramsey Scott, Which Was Published in 2016

This digital proof is provided for free by UDP. It documents the existence of the book The Narco- Imaginary: Essays Under The Influence by Ramsey Scott, which was published in 2016. If you like what you see in this proof, we encourage you to purchase the book directly from UDP, or from our distributors and partner bookstores, or from any independent bookseller. If you find our Digital Proofs program useful for your research or as a resource for teaching, please consider making a donation to UDP. If you make copies of this proof for your students or any other reason, we ask you to include this page. Please support nonprofit & independent publishing by making donations to the presses that serve you and by purchasing books through ethical channels. UGLY DUCKLING PRESSE uglyducklingpresse.org THE NARCO IMAGINARY UGLY DUCKLING PRESSE The Narco-Imaginary: Essays Under The Influence by Ramsey Scott (2016) - Digital Proof THE NARCO- IMAGINARY Essays Under the Influence RAMSEY SCOTT UDP :: DOSSIER 2016 UGLY DUCKLING PRESSE The Narco-Imaginary: Essays Under The Influence by Ramsey Scott (2016) - Digital Proof THE Copyright © 2016 by Ramsey Scott isbn: 978-1-937027-44-5 NARCO- DESIGN AnD TYPEsETTING: emdash and goodutopian CoVEr PRINTING: Ugly Duckling Presse IMAGINARY Distributed to the trade by SPD / Small Press Distribution: 1341 Seventh Street, Berkeley, CA 94710, spdbooks.org Funding for this book was provided by generous grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts, and the Department of Cultural Affairs -

Family Practice Grand Rounds Early Diagnosis and Treatment

Family Practice Grand Rounds Early Diagnosis and Treatment of Alcoholism Antonnette V. Graham, RN, MSW, David Sedlacek, PhD, Kenneth G. Reeb, MD, and Jay S. Thompson, MD Cleveland, Ohio ANTONNETTE V. GRAHAM, RN, MSW This patient is a very attractive, 34-year-old, single (Assistant Professor, Department of Family Med woman. She is currently employed as a school icine): Today we are going to discuss what many psychologist and is finishing her dissertation for people believe is the number-one health problem her doctorate in psychology. She lives alone in a in the United States—alcoholism.1 It is often felt middle-class suburb of a large northeastern city. that alcoholism affects the lives of more patients, She is the eldest of four children. Her father is a either because of their own drinking or because retired college administrator, and her mother is of the drinking of a family member, than any other currently employed as an executive secretary. disease. There is no family history of alcoholism. Miss Current prevalency estimates of alcoholism and Carr’s parents and siblings drink socially. On Miss alcohol-related problems indicate that in many pa Carr’s initial visit to the Family Practice Center, tients these problems go undetected by physicians her physical examination and laboratory values until they become manifested by severe physical were normal. sequelae. Current thinking among experts is that MRS. GRAHAM: Thank you, Miss Carr, for early intervention leads to better prognosis. No attending our Grand Rounds today. I’d like to longer is it felt that alcoholics must “ bottom out” focus today’s discussion on how alcohol has af before help can be effective. -

Recovery As Penance

MOJ Addiction Medicine & Therapy Literature Review Open Access Recovery as penance Review Volume 5 Issue 6 - 2018 The core of democracy is free choice. Drug users & abusers do not have a free choice. Their choice of rehabilitation has been decided Richard Willnot for them by custodians of the puritan ethos. It is total abstinence to University of California at San Diego, USA prevent the sin of intoxication. Drug recovery today is penance. It is based on the values of cultural Puritanism. Puritanism, the first Correspondence: Richard Willnot, University of California at American religion, is what makes drug recovery about religion. San Diego, USA, Email Anything else would be sin. Received: October 30, 2018 | Published: November 21, 2018 If a person displays some behaviour which warrants closer scrutiny or arrest, our justice system (embedded in our puritan culture) will allow for the forgiveness of sin if the person converts to the semi- secular religion known as AA (Alcoholics Anonymous) & other Twelve Step ‘pogroms’: Narcotics Anonymous, Cocaine Anonymous, AA literature: the dry drunk Marijuana Anonymous & even Sex Addict Anonymous. Now that you’re in recovery, ‘dry drunk’ is a term you will hear The Recovery Book (Mooney and Eisenberg, 1992) is a general fairly often… a person who acts intoxicated—giggly, hysterical, orientation to Alcoholics Anonymous and other Twelve Step Recovery uncontrollable without having used a drug or had a drop to drink. Groups. On page 253 of this 600 page book, those addicts who are on The second type of dry drunk is the person who behaves like an their deathbed are encouraged not to take any “mood altering” drugs active addict—resentful, inconsiderate, not attending AA meetings, which may compromise their sobriety and lead to relapse. -

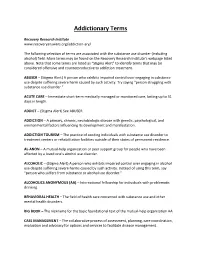

Addictionary Terms

Addictionary Terms Recovery Research Institute www.recoveryanswers.org/addiction-ary/ The following selection of terms are associated with the substance use disorder (including alcohol) field. More terms may be found on the Recovery Research Institute’s webpage listed above. Note that some terms are listed as “Stigma Alert” to identify terms that may be considered offensive and counterproductive to addiction treatment. ABUSER – (Stigma Alert) A person who exhibits impaired control over engaging in substance use despite suffering severe harm caused by such activity. Try saying “person struggling with substance use disorder.” ACUTE CARE – Immediate short-term medically managed or monitored care, lasting up to 31 days in length. ADDICT – (Stigma Alert) See ABUSER ADDICTION – A primary, chronic, neurobiologic disease with genetic, psychological, and environmental factors influencing its development and manifestation. ADDICTION TOURISM – The practice of sending individuals with substance use disorder to treatment centers or rehabilitation facilities outside of their states of permanent residence. AL-ANON – A mutual-help organization or peer support group for people who have been affected by a loved one’s alcohol use disorder. ALCOHOLIC – (Stigma Alert) A person who exhibits impaired control over engaging in alcohol use despite suffering severe harms caused by such activity. Instead of using this term, say “person who suffers from substance or alcohol use disorder.” ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS (AA) – International fellowship for individuals with problematic drinking. BEHAVIORAL HEALTH – The field of health care concerned with substance use and other mental health disorders. BIG BOOK – The nickname for the basic foundational text of the mutual-help organization AA. CASE MANAGEMENT – The collaborative process of assessment, planning, care coordination, evaluation and advocacy for options and services to facilitate disease management. -

AUTHOR Alcohol Abuse Curriculum Guide for Nurse Practitioner Faculty. Health Professions Education Curriculum National Inst. On

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 251 763 CG 017 892 AUTHOR Hasselblad, Judith TITLE Alcohol Abuse Curriculum Guide for Nurse Practitioner Faculty. Health Professions Education Curriculum Resources Series. Nursing 3, INSTITUTION Informatics, Inc., Rockville, Md.; National Clearinghouse for Alcohol Information (DHHS), Rockville, Md. SPONS AGENCY National Inst. on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (DHHS), Rockville, Md. REPORT NO DHHS(ADM)-84-1313 PUB DATE 84 CONTRACT ADM-281-79-0001 NOTE 176p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Alcohol Education; *Alcoholism; Curriculum Guides; Family Problems; *Identification; Individual Needs; *Nurse Practitioners; Physical Health; Psychological Needs; *Rehabilitation; Teachers ABSTRACT The format for this curriculum guide, written for nurse practitioner faculty, consists of learningobjectives, content outline, teaching methodology suggestions, references and recommended readings. Part 1 of the guide, Recognition of Early and Chronic Alcoholism, deals with features of alcoholism such as epidemiological data and theories, definitions, attitudes, and approaches to alcoholism; special populations and their needs; and biophysical and psychosocial consequences of alcoholism. Part 2, Diagnosis of Early and Chronic Alcoholism, addresses the assessment and diagnosis of alcoholism in a primary care setting, with emphasis on the assessment interview. Part 3, Management of Early and Chronic Alcoholism, deals with strategies used in the recovery process, e.g., -

The Rhetoric of Substance Use Disorder Morgan Carter Kennesaw State University, [email protected]

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Master of Arts in Professional Writing Capstones Professional Writing Spring 4-24-2019 The Rhetoric of Substance Use Disorder Morgan Carter Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/mapw_etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Carter, Morgan, "The Rhetoric of Substance Use Disorder" (2019). Master of Arts in Professional Writing Capstones. 48. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/mapw_etd/48 This Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Professional Writing at DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in Professional Writing Capstones by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rhetoric of Substance Use Disorder By Morgan Carter A capstone project submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Professional Writing in the Department of English In the College of Humanities and Social Sciences of Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia 2019 Contents Introduction 1 Literature Review 4 Chapter One: Narrative 15 Chapter Two: Critique 30 Chapter Three: Conclusion 45 Works Cited 49 iii For those who are still sick and suffering and for the kids caught in the cross-fire Introduction The addict and alcoholic are members of society who are continuously marginalized by the language used to describe them, both by media coverage and everyday language. The nature of their disease creates a space of self-identification that is outside the norm of normal illness. -

Download Download

[FIR 15.1–2 (2020) 204–205] Fieldwork in Religion (print) ISSN 1743–0615 https://doi.org/10.1558/firn.18365 Fieldwork in Religion (online) ISSN 1743–0623 BOOK REVIEW Calhoun, Scott (ed.) 2018. U2 and the Religious Impulse. London: Bloomsbury. xvi + 236 pp. ISBN: 9781501332395 £90.00 (hbk); ISBN: 9780567690210 £28.99 (pbk); ISBN: 9781350032552 £26.09 (e-book). Reviewed by: Barbara Pemberton, Ouachita Baptist University, AR, USA [email protected] Keywords: Irish rock; Christianity; U2; popular music; religion and media; popular cul- ture; musicology. U2 and the Religious Impulse, edited by Scott Calhoun, Professor of English at Cedarville Uni- versity, USA, is a collection of multidisciplinary essays considering the Irish rock band U2 and the enduring spiritual influence it has on fans. The aim of this book is to address new questions: “why the religious impulse in fans is so satisfyingly met by U2 … and why a broader group of religiously inclined fans are interested in U2” (p. 6). Calhoun has gath- ered an impressive group of scholars from a variety of fields including literature, theol- ogy, music, ethics, history, and political science, all providing excellent, thought-provoking essays. While all of the contributors share an interest in popular culture, several profess life- long U2 fandom. Since its formation by four musicians in 1976, U2 has been writing and giving landmark performances around the world, including the highest grossing concert ever—the 360° Tour. These critically acclaimed and immensely popular artists are unapologetically guided by their Christian faith, and their lyrics display a spiritual depth far beyond what may usu- ally be expected from rock music. -

Surrender: an Alchemical Act in Personal Transformation Moze, Mary Beth G

Journal of Conscious Evolution Volume 3 Article 10 Issue 3 Issue 03/2007 May 2018 Surrender: An Alchemical Act in Personal Transformation Moze, Mary Beth G. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, Cognition and Perception Commons, Cognitive Psychology Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons, Social Psychology Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Sociology of Religion Commons, and the Transpersonal Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Moze, Mary Beth G. (2018) "Surrender: An Alchemical Act in Personal Transformation," Journal of Conscious Evolution: Vol. 3 : Iss. 3 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal/vol3/iss3/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Conscious Evolution by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : Surrender: An Alchemical Act in Personal Transformation Surrender: An Alchemical Act in Personal Transformation Mary Beth G. Moze1 Abstract This article is the result of inquiring about human resistance to change. Specifically, it focuses on the act of surrender which engages, rather than avoids, the process of transformation. Due to the relatively sparse amount of literature on the subject of surrender, additional literature which parallels and compliments the subject is creatively woven in. The author comfortably injects criticism and interpretation of the literature and intermittently offers suggestions for further research efforts. -

Surrendering to Jesus”

Season 1, Episode 2: “Surrendering to Jesus” Hey there, friends! We are going to continue something we started last week and that is the whole theme of telling our stories… today, with a little bit of an emphasis on surrender. I'm going to continue telling you part of my story in hopes that you can see how surrender was a big part of how I came to meet my husband and marry my husband and come into the ministry that I have today. So if you didn't listen to last week's episode, go back and do that and it'll kinda catch you up to speed. But I'm going to start out by sharing with you some of what I was going through before I met my husband, John, but after I had that big turning point in my life where I really started to fall in love with Jesus. I told you last week that I was involved in Bible study and I was really, really loving studying God's word and knowing him through his word and that's where I fell in love with him– it was just in his word. And as I was studying with this group across town at another church, I just kept thinking, Wow, we need to do this at my church! The women in my church need Bible study. (We did not have a formal Bible study in my church at that time.) So I went to talk to my friend, Happy, that I mentioned to you last week. -

Bernard Grindrod the SINGAPORE DEBACLE

Bernard Grindrod THE SINGAPORE DEBACLE – by Bernard Grindrod The moment of surrender was tense in the humid climate and low clouds over Singapore on that afternoon of Sunday, the fifteenth. It was February 1942. Lieutenant General Sir Arthur E. Percival, together with a few carefully selected senior staff officers, dismounted on Bukit Timah Road near the Ford Factory and walked across no man’s land to a hastily erected table on which a single document lay. There were British Officers carrying the Union Jack and the white flag. They reached the table and waited ---- a humiliating wait before Yamashita appeared and spoke. Cyril Wild translated as best he could with his limited knowledge of Japanese. They were already over an hour late for the appointment set up the previous day for four thirty and the Japanese General was angry. He spoke directly to Percival ignoring his own translator: Yamashita: “I wish your replies to be brief and to the point. I will listen only to unconditional surrender. Have you captured any Japanese soldiers?” Percival: “None”. Yamashita: “What about Japanese prisoners?” Percival: “All who have been interned have been sent to India. Their lives are fully protected.” Yamashita: “I want to hear whether you wish to surrender.” Percival: “Will you give me until tomorrow?” Yamashita: “I cannot wait.” Percival: “Give me five hours.” Yamashita: “Then we will continue to attack meanwhile.” General Percival remained silent but General Yamashita insisted on an answer and Percival finally replied, “Yes!” In this single word, his lateness, his inability to negotiate with strength knowing full well from current intelligence the Japanese were short of ammunition and outnumbered three to one, and his inability to make decisions painted the true picture of why Singapore surrendered. -

Editorial • Utrecht Conference • News • an Elisad Member: SIIS, Madrid • a New Member: Drugtext Foundation • Publications • Onlinedocs Editorial • Agenda

n° 31 - Nov. 2010 - 1 • Editorial • Utrecht conference • News • An Elisad member: SIIS, Madrid • A new member: Drugtext Foundation • Publications • OnlineDocs Editorial • Agenda HE AUTUMN has really come to my part of Europe with dark and misty nights. I still remember the nice and warm last day in Utrecht, when some of us took the wal- Tking tour in the beautiful ancient parts of the city. The guide was very enthusiastic Our next of her hometown and described lively all the monuments in the city centre. She specially annual conference is pointed out one of the local coffee shops and described little about their existence in planned 6-8 October 2011 society. at the French Monitoring Centre on Drugs & Drug Anyway I am glad that I bought myself a generous piece of well ripened Reypenaer Addiction (OFDT) cheese to bring home. Even though there is a Dutch cheese shop in my part of the city cen- Paris tre of Stockholm. Quite international so far up in the north of Europe, is n't it? This is my first editorial text as the new Chair of Elisad. First of all I want to make some reflections on our languages. I feel pleased to use English as the lingua franca among us in Elisad, some of you may have heard me mention “broken English”. That is what we all have in common and I want to emphasize that no one should excuse for their bad English. It is a charming bit of Elisad networking that we do understand each other so well! And please forgive me if my English is not so perfect at all times (English prepositions - damned!). -

Persuasions of the Wild Writing the Moment a Phenomenology

PERSUASIONS OF THE WILD WRITING THE MOMENT A PHENOMENOLOGY Jana Milloy Bachelor of Fine Arts, Simon Fraser University, 1994 Master of Arts, Simon Fraser University, 2004 DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Faculty of Education O Jana Milloy 2007 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY 2007 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Jana Milloy Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Research Project: Persuasions of the Wild Writing the Moment A Phenomenology Examining Committee: Chair: Lynn Fels, Assistant Professor Stephen Smith, Associate Professor Senior Supervisor Celeste Snowber, Associate Professor Charles Bingham, Assistant Professor Dr. Stuart Richmond, Professor, Faculty of Education InternalIExternal Examiner Dr. Carl Leggo, Professor, Faculty of Education, UBC External Examiner Date: September 27,2007 SIMON FIIASEII UNIVERSITY Ll BRARY Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the "Institutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/l892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work.