Vedantic Outreach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May I Answer That?

MAY I ANSWER THAT? By SRI SWAMI SIVANANDA SERVE, LOVE, GIVE, PURIFY, MEDITATE, REALIZE Sri Swami Sivananda So Says Founder of Sri Swami Sivananda The Divine Life Society A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION First Edition: 1992 Second Edition: 1994 (4,000 copies) World Wide Web (WWW) Reprint : 1997 WWW site: http://www.rsl.ukans.edu/~pkanagar/divine/ This WWW reprint is for free distribution © The Divine Life Trust Society ISBN 81-7502-104-1 Published By THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttar Pradesh, Himalayas, India. Publishers’ Note This book is a compilation from the various published works of the holy Master Sri Swami Sivananda, including some of his earliest works extending as far back as the late thirties. The questions and answers in the pages that follow deal with some of the commonest, but most vital, doubts raised by practising spiritual aspirants. What invests these answers and explanations with great value is the authority, not only of the sage’s intuition, but also of his personal experience. Swami Sivananda was a sage whose first concern, even first love, shall we say, was the spiritual seeker, the Yoga student. Sivananda lived to serve them; and this priceless volume is the outcome of that Seva Bhav of the great Master. We do hope that the aspirant world will benefit considerably from a careful perusal of the pages that follow and derive rare guidance and inspiration in their struggle for spiritual perfection. May the holy Master’s divine blessings be upon all. SHIVANANDANAGAR, JANUARY 1, 1993. -

Bareilly Dealers Of

Dealers of Bareilly Sl.No TIN NO. UPTTNO FIRM - NAME FIRM-ADDRESS 1 09107300009 BE0001281 RAJ CROCKERY CENTER HOSPITAL ROAD BAREILLY 2 09107300014 BE0008385 SUPER PROVISION STORE PANJABI MARKET, BAREILLY. 3 09107300028 BE0006987 BHATIA AGEMCIES 89 CIVIL LINES, BAREILLY. 4 09107300033 BE0010659 VIJAY KIRANA STORE SUBHAS NAGAR BY 5 09107300047 BE0001030 MUKUT MURARI LAL WOOD VIKRATA CHOUPLA ROAD BY 6 09107300052 BE0008979 GARG BROTHERS TOWN HALL BAREILLY. 7 09107300066 BE0001244 RAJ BOOK DEPOT SUBHAS MKT BY 8 09107300071 BE0000318 MONICA MEDICAL STORE 179, CIVIL LINES, BAREILLY. 9 09107300085 BE0001762 RAM KUMAR SUBASH CHAND AONLA ,BAREILLY. 10 09107300090 BE0009124 GARU NANA FILLING STN KARGANA BAREILLY. 11 09107300099 BE0005657 KHANDUJA ENTERPRISES GANJ AONLA,BAREILLY. 12 09107300108 BE0004857 ADARSH RTRADING CO. CHOPUPLA ROAD BY 13 09107300113 BE0007245 SWETI ENTERPRISES CHOUPLA ROAD BY 14 09107300127 BE0011496 GREEN MEDICAL STORE GHER ANNU KHAN AONLA BAREILLY 15 09107300132 BE0002007 RAMESHER DAYAL SURENDRA BHAV AONLA BAREILLY 16 09107300146 BE0062544 INDIAN FARMERS FERTILISERS CORP AONLA, BAREILLY. LTD 17 09107300151 BE0007079 BHARAT MECH STORE BALIA AONLA, BAREILLY. 18 09107300165 BE0011395 SUCHETA PRAKASHAN MANDIR BAZAR GANJ AONLA BAREILLY 19 09107300170 BE0003628 KICHEN CENTER & RAPAIRS JILA PARISAD BY 20 09107300179 BE0006421 BAREILLY GUN SERVICE 179/10 CIVIL LINES,BAREILLY 21 09107300184 BE0004554 AHUJA GAS & FAMILY APPLIANCES 179 CIVIL LINES, BAREILLY. 22 09107300198 BE0002360 IJAAT KHA CONTRACTOR SIROLY AONLA BAREILLY. 23 09107300207 BE0003604 KRISHAN AUTAUR CONTRACTOR BAMANPURI BAREILLY. 24 09107300212 BE0009945 PUSTAK MANDIR SUBASH MKT BY 25 09107300226 BE0005758 NITIN FANCY JEWELERS CANAAT PLACE MKT BY 26 09107300231 BE0005520 DEHLI AUTO CENTER CAROLAAN CHOUPLA ROAD BY 27 09107300245 BE0003248 KHANN A PLYWOOD EMPORIUM CIVIL LINES, BAREILLY. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Seventh Goswami."

Dedication Preface 1. Prologue 2. Family Lineage 3. Birth and Infancy 4. Schooling 5. Marriage & Studies in Calcutta 6. College 7. Orissa 8. Deputy Magistrate 9. Preaching Days Begin 10. The Öhäkura in Puré 11. The Chastisemant of Bisakisen 12. Vaiñëava Studies and Two Mahätmäs 13. Royal Conspiracy 14. Kåñëa-saàhitä and Other Works 15. Initiation and Çréla Jagannätha Däsa Bäbäjé 16. Bhakti Bhavan 17. Bankim Chandra and a Flow of Books 18. Discovery of Lord Çré Caitanya's Birthsite 19. Preaching the Holy Name 20. A Mighty Pen 21. Retirement and Expansion of Preaching 22. His Preaching Reaches the Western World 23. Preaching and Publishing Until the Last 24. Bhakti Kuti and Svänanda-sukhada-kuïja 25. Acceptance of Bäbäjé-veña 26. Last Days 27. Summary of Life and Qualities 28. His Daily Schedule 29. His Character 30. His Writing 31. His Predictions 32. Appendices 33. Glossary A Biography of His Divine Grace Çréla Saccidänanda Bhaktivinoda Öhäkura (1838-1914) by Rüpa-viläsa däsa Adhikäré Edited by Karëämrta däsa Adhikäré "I have not yet seen the Six Goswamis of Vrindavan, but I consider you to be the Seventh Goswami." Shishir Kumar Ghosh (1840-1911) Amrita Bazar Patrika, Editor and founder, in a letter to glorify Çréla Bhaktivinoda Öhäkura Dedication To His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupäda, my eternal spiritual master, who delivered the merciful teachings of the Vaiñëava äcäryas to the suffering world. I pray that he may be a little 2 pleased with this attempt to glorify Çréla Sac-cid-änanda Bhaktivinoda Öhäkura. namo bhaktivinodäya sac-cid-änanda-nämine gaura-çakti-svarüpäya rüpänuga-varäya te namaù-obeisances; bhaktivinodäya-unto Çréla Bhaktivinoda Öhäkura; sat-cit-änanda-nämine-known as Saccidänanda; gaura-(of) Lord Caitanya; çakti-energy; svarüpäya-unto the personified; rüpa-anuga- varäya-who is a revered follower of Çréla Rüpa Gosvämé; te-unto you. -

BOARD of SCHOOL EDUCATION HARYANA BHIWANI Page: 1 SIP Fee Received List for Exam July - 2018 DIST NAME : 01 : AMBALA INST

BOARD OF SCHOOL EDUCATION HARYANA BHIWANI Page: 1 SIP Fee Received List for Exam July - 2018 DIST NAME : 01 : AMBALA INST. NAME : 501001 : LALA AMI CHAND MONGA MEMORIAL COLLEGE OF EDUCATION , ABDULLAH GARH Srl. Roll No. Candidate's Name / Father's Name Srl. Roll No. Candidate's Name / Father's Name Year : 1st Year 30 5216010033 BIRENDRA KUMAR / PRATAP SAW 1 5117010001 ANJALI RATHORE / JAY SINGH 31 5216010034 GAUTAM KUMAR / UMESH SAW 2 5117010002 HIMANSHU KUMAR SINGH / ARUN 32 5216010037 SANTOSH KUMAR / RADHE SHAW 3 5117010003 SEEMA DEVI / SUBE SINGH 4 5117010004 TARUN KUMAR / MOOL RAJ 5 5117010008 MANDEEP KAUR / SOAM SINGH 6 5117010012 SAHIL / RAKESH 7 5117010023 JITENDRA KUMAR / RUPNARAYAN 8 5117010024 LAKSHMI KUMARI / CHANDRIKA 9 5117010025 CHHOTU KUMAR / BIRENDRA 10 5117010026 VICKY / GURCHARAN SINGH 11 5117010028 KULDEEP KAUR / SURJEET SINGH 12 5117010033 ARCHANA KUMARI / RAJ KUMAR 13 5117010034 SANJAY KUMAR / VISHWANATH 14 5117010035 ANITA KUMARI / RAMPUKAR RAY 15 5117010036 VANDANA KUMARI / BRAHM DEV 16 5117010037 SANJEEV KUMAR / KAILASH DAS 17 5117010038 PRERNA KUMARI / VIJAY KUMAR 18 5117010039 DEEPENDRA PRAKASH / 19 5117010041 BHAGWAN PRAKASH / RAM SAGAR 20 5117010042 KAJAL KUMARI / CHANDESHWAR 21 5117010044 SARITA KUMARI / CHANDESHWAR 22 5117010045 RAMNIVAS SINGH / RAGHUNATH Year : 2nd Year 23 5216010002 DHARMENDRA KUMAR / PRATAP 24 5216010004 MD MIRZA GALIB / MD HAIDAR ALI 25 5216010005 RANJAN KUMAR PANDAY / 26 5216010013 RICHA SHARMA / KRISHAN KANT 27 5216010016 NEHA / RANDHIR SINGH 28 5216010023 PUSHPAM KUMARI / DILEEP SINGH 29 5216010032 PRSHANT KUMAR / CHITRANJAN BOARD OF SCHOOL EDUCATION HARYANA BHIWANI Page: 2 SIP Fee Received List for Exam July - 2018 DIST NAME : 01 : AMBALA INST. NAME : 501002 : LORD KRISHNA COLLEGE OF EDUCATION , ADHOYA Srl. -

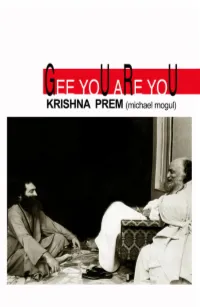

Chapter-1 Gee As You

Gee You Are You Gee You Are You Krishna Prem (Michael Mogul) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Copyright © 2011 by Michael Mogul (Krishna Prem) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the author. The only exception is by a reviewer, who may quote short excerpts in a review. Printed in the United States of America First Printing: July, 2011 ISBN-978-1-61364-318-1 About the Author Gee You Are You is a book about a life’s journey from here to here. On the front cover is a picture of me at thirty-three years of age, sitting on a cold marble floor in front of my teacher and friend, Osho, in Pune, India. On the back cover I am the ripe old age of sixty-six. As Bob Dylan once sang, “Oh, but I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now.” Yes, my body is now twice as old and yet I feel half my age… the magic of meditation. Through my years of peeling the layers of my own onion, I have turned my life from maditation in the outer world to meditation in my inner world. While reading this book, you will be constantly challenged to witness that you are not so much your conditioning in the marketplace of your hometown, but more that the world is appearing in you… that you are not the mind. -

Śrī Vyāsa-Pūjā A

Śrī v yāsa-pūjā Śrī vyāsa-pūjā 13 August 202013 A. The Appearanceof HisDay Divine Grace C. Bhaktivedanta Prabhupāda Swami THE MOST BLESSED EVENT The Appearance Day of Our Beloved Spiritual Master His Divine Grace Oṁ Viṣṇupāda Paramahaṁsa Parivrājakācārya Aṣṭottara-śata Śrī Śrīmad A. C. BHAKTIVEDANTA SWAMI PRABHUPĀDA Founder-Ācārya of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness Śrī vyāsa-pūjā Śrī vyāsa-pūjā THE MOST BLESSED EVENT The Appearance Day of Our Beloved Spiritual Master 13 August 2020 His Divine Grace Oṁ Viṣṇupāda Paramahaṁsa Parivrājakācārya Aṣṭottara-śata Śrī Śrīmad A. C. BHAKTIVEDANTA SWAMI PRABHUPĀDA Founder-Ācārya of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness 3 Set in The Brill and Futura Round Condensed display at The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust Africa © 2020 The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust Africa The copyrights for the offerings presented in this book remain with their respective authors. Quotes from books, lectures, letters and conversations by His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupāda © 2020 Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, Inc. Cover and artwork courtesy of The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, Inc. www.bbtafrica.co.za y www.bbt.org y www.krishna.com All Rights Reserved 3 CONTENTS Preface vii Acknowledgements ix THE MEANING OF VYĀSA-PŪJĀ 1 ŚRĪ GURVĀṢṬAKAM 5 Offerings by 4 SANNYĀSĪS 23 INITIATED DISCIPLES 39 GRANDDISCIPLES, GREAT-GRANDDISCIPLES & OTHER DEVOTEES 47 ISKCON CENTRES 277 THE BHAKTIVEDANTA BOOK TRUST 291 OTHER SOURCES 295 3 PREFACE 4 HEMANT BHAGA z THIS YEAR’S EDITION of Śrīla Prabhupāda’s reflect on one’s own life to understand the profound pan-African Vyāsa-pūjā book published effect of this mercy. -

The Last English Saint an Obituary of Sri Madhava Ashish by Donald

The Last English Saint An Obituary of Sri Madhava Ashish by Donald Eichert that appeared in an Indian news magazine The death of Sri Madhava Ashish in April 1997 after a long illness rounded off a remarkable chapter in the long story of Indian mysticism. In a convergence of fulfilled aspiration that almost defies credence the tiny hamlet of Mirtola in Almora district in northern India became the focus of no fewer than four lives of spiritual attainment. Madhava Ashish was the last in a line of gurus which can stand comparison with the Naropa-Marpa-Milarepa parampara of the Tibetan tradition. His commanding presence belied a gentle nature almost feminine in nuance. When, as rishis must at times, Madhava Ashish displayed anger it was shadowed by a kind of sadness, as though the higher consciousness watched compassionately. Born in Edinburgh in 1920, the great-grandson of a Scottish laird, he was christened Alexander Phipps. His mother, a Campbell, had been born in Sri Lanka, then Ceylon, and had married a colonel in the Indian Army. The Phippses also had West Indian connections. Young Phipps attended Sherborne School in Taunton, Somersetshire, acquiring the public school manner which he never quite lost in fifty years as a Vaishnav monk. When he moved on to Chelsea Polytechnic to study aeronautical engineering his accent was mocked by his fellow students. The outbreak of World War II found Phipps a qualified engineer in a reserved occupation. He was set to supervising the construction of invasion gliders, and when it was decided to build them in India he came out to take up the work at Dumdum, Calcutta. -

Bibliography on Yoga

Bibliography on Yoga Kalanidhi Reference Library Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts Ministry of Culture 1, C.V. Mess, Janpath, New Delhi-110001 www.ignca.nic.in 1 Patanjali Yoga-sutra. 181.452 PAT. 45104 Patanjali Aphorisms of yoga. 181.452 PAT. LD20632 Patanjali Yoga sutras of Patanjali: effortless being. 181.452 PAT. 25174 Patanjali Die Wurzeln des yoga. 181.452 PAT. G2001 Patanjali Samga Yogadarsana or Yogadarsana of Patanjali. 181.45 PAT. JD482 Patanjali Yoga-sutras. 181.452 PAT. 5524 Patanjali Samga yogadarsana: with the commentary of Vyasa. PAT. R2365 Patanjali La voie du yoga darishana : Les aphorismes de Patanjali, Patanjalayogadarshanam 181.452 PAT. G1786 Patanjli Science of yoga. 181.452 PAT. 17371 2 Patanjali Yoga philosophy of Patanjali. 181.45 PAT. 26419 Patanjali Aphorisms of Yoga. 181.45 PAT. 63217 Patanjali Aphorisms of Yoga. 181.452 PAT. VS431 Sankaracarya Sankara on the Yoga-sutra-vivarana sub-commentary to Vyasabhasya on the Yoga-sutras of Patanjali: Samadhi- pada. 181.452 SAN. 25581 Sankaracharya Complete commentary by Sankara on the Yog sutras: a full translation of the newly discovered text. 181.452 SAN. 25559 Sivananda Raja yoga. 181.45 SIV. 48266 Yardi, M.R. Yoga of Patanjali. 181.452 YAR. 10533 Rama Prasada, tr. Patanjali's yoga sutras. 181.452 PAT. 11472 Koelman, Gaspar M. Patanjala Yoga : from related ego to absolute self. 181.452 KOE. JD553 3 Slater, V. W. Raja-Yoga. 181.45 SLA. G2014 Taimni, I. K. Die wissenschaft des Yoga : Die Yoga-Sutren des Patanjali in Sanskrit. 181.452 TAI. G2018 Yesudian, Selvarajan Raja-Yoga : Yoga in den zwei welten. -

International Journal of English and Education "I Am Become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds." (Gita, 11.32)

International Journal of English and Education 333 ISSN: 2278-4012, Volume:3, Issue:4, October 2014 The Bhagavad Gita – The Politics of Interpretation and its Interpretation in Politics Ms. Mohua Dutta, Research Scholar Department of Modern Indian Languages and Literary Studies, University of Delhi Abstract: The Bhagavad Gita is one of the major sacred texts of Hindu mythology, and is one of the perennial sources of spiritual knowledge. However, during the time of Indian national struggle for freedom, this sacred text was interpreted and re-interpreted numerous times by each prominent nationalist leader, sometimes to justify violence, sometimes to ensure mass participation in the Satyagraha movement. In his interpretation, Tilak found that The Gita teaches the philosophy of activism and energism (Karma yoga). Karma yoga means purging the soul of desires, so that the action performed is free from any materialistic attachments and desireless of its outcome. Gandhi on the other hand, interpreted it as an allegorical representation of the spiritual war going on between the forces of Good and the forces of Evil. Gandhi thus converted the greatest Indian war epic into an elaborate set-up to preach the importance of truth and non-violence. However, to Ambedkar, it was neither a sacred text nor a treatise on philosophy, but a politically motivated “counter-revolution” by the Brahmins to establish their supremacy by defending Chaturvarna, and securing its observance in practice. In my paper, I propose to underline such politics of interpretation of The Gita and understand how each stand has sought justification from the text. Keywords: The Bhagavad Gita, Karma yoga, Tilak, Gandhi, Ambedkar "I am become death, the destroyer of worlds." (Gita, 11.32) These words from The BhagavadGita is what J. -

Experiences of a Pilgrim Soul

EXPERIENCES OF A PILGRIM SOUL Experiences Of A Pilgrim Soul Kavi Yogi Mahrshi Dr Shuddhananda Bharathi (Auto Biography) Published BY Shuddhananda Library, Thiruvanmiyur, Chennai 600 041. Ph: 97911 77741 Copy Right : @Shuddhananda Yoga Samaj(Regd), Shuddhananda Nagar, Sivaganga - 630 551 EXPERIENCES OF A PILGRIM SOUL EXPERIENCES OF A PILGRIM SOUL PART I 1. TO FELLOW PILGRIMS We are all Pilgrims of Eternity coming from an unknown past, living in a multicol- oured universe and passing into a mystic future. Whence we come and where we go, we know not: but we come and go playing our role in this evolutionary drama of Existence! Who exists, why, how and who started this cosmic play and what is its goal? – every intelligent man and woman must find out an answer to these age–long inquiries. Through the dark inferno, burning purgatory and pleasing paradise of this mounting Divina Commedia, a rhythmic heartbeat keeps time to a mystic song whose refrain is, “I am Aum”. Who is this ‘I’—that is the first person in us, and the baffling personality in the second and the third persons? That universal ‘I’ in the individual, is the Pilgrim Soul here. Fellow Pilgrims, pray walk with him as he talks with you. These are random footprints left on the sands of Time by the patient Pilgrim whose plodding steps met with grim trials in the ups and downs of human destiny. Hard was his lonely journey, long his search in the tangled woodlands of cosmic life and high was the aim of his inner aspiration guided and fulfilled by a Pure Almighty Grace–Light. -

I MET SRI MADHAVA ASHISH (1920–1997), the Third Mirtola Guru, in September 1978

Mirtola I MET SRI MADHAVA ASHISH (1920–1997), the third Mirtola guru, in September 1978. This was just a few months after joining the Theosophical Society. In an effort to understand H.P. Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine and the Stanzas of Dzyan on which it is based, I came across Ashish’s books of commentary on those stanzas. These books, Man, The Measure of All Things (coauthored with his guru, Sri Krishna Prem) and Man, Son of Man, opened up an inner world for me that I did not know existed. This caused me to go to India and to meet him. Our first meeting at Mirtola led to annual visits with Ashish and a rich correspondence for nineteen years until his passing in 1997. Mirtola is a farm of sixty acres with a Hindu temple at its center, about eighteen kilometers from Almora, a well-known Indian town in the foothills of the Himalayas northeast of New Delhi and near the borders of Tibet and Nepal. But Mirtola is more than that. Its rich history, with deep Theosophical roots, has been a source of wisdom since its founding in 1929. At the passing of Sri Krishna Prem in 1965, Sri Madhava Ashish became head of the Mirtola ashram and remained so until his passing in 1997. From that time, the Mirtola ashram has been maintained by Sri Madhava Ashish’s stepson and follower, Sri Dev Ashish. In addition to his several published books and articles, Madhava Ashish collected anecdotes and reminiscences about the history of Mirtola, about the two gurus who preceded him, Sri Yashoda Mai and Sri Krishna Prem, and about associated figures prominent in Theosophical history.