Download Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guest Artist Cello Concert Bryan Hayslett

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Guest Artist Cello Concert Bryan Hayslett Tuesday, October 28, 2014 • 7:30 p.m. Belhaven University Center for the Arts • Concert Hall There will be a reception after the program. Please come and greet the performer. Please refrain from the use of all flash and still photography during the concert. Please turn off all pagers and cell phones. PROGRAM Please hold applause until intermission. Cello Suite No. 6 in D Major, BWV 1012 Johann Sebastian Bach • 1685 - 1750 I. Prelude Unlocked, 1. Make Me a Garment Judith Weir • b. 1954 Unlocked, 2. No Justice A Portrait in Greys Marissa Deitz Wall • b. 1990 Suite No. 6, 2. Allemande J.S. Bach Suite No. 6, 3. Courante Age of the Deceased (Six Months in Chicago) Drew Baker • b. 1978 INTERMISSION Suite No. 6, 4. Sarabande J.S. Bach Suite No. 6, 5. Gavotte A Portrait in Greys Keith Kusterer • b. 1981 Unlocked, 5. Trouble, trouble Judith Weir Suite No. 6, 6. Gigue J.S. Bach A Portrait in Greys by William Carlos Williams Will it never be possible to separate you from your greyness? Must you be always sinking backward into your grey-brown landscapes— And trees always in the distance, always against a grey sky? Must I be always moving counter to you? Is there no place where we can be at peace together and the motion of our drawing apart be altogether taken up? I see myself standing upon your shoulders touching a grey, broken sky— but you, weighted down with me, yet gripping my ankles,—move laboriously on, where it is level and undisturbed by colors. -

Bach Unbuttoned

Bach Unbuttoned ANA DE LA VEGA ALEXANDER SITKOVETSKY · RAMÓN ORTEGA QUERO CYRUS ALLYAR · JOHANNES BERGER WÜRTTEMBERGISCHES KAMMERORCHESTER HEILBRONN Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Suite No. 2 in B Minor (For Flute, Strings & Basso Continuo), BWV 1067 13 VII. Badinerie 1. 24 Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D Major (for Flute, Violin & Harpsichord), BWV 1050 Total playing time: 62. 26 1 I. Allegro 9. 22 2 II. Affetuoso 5. 54 3 III. Allegro 5. 11 Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 in G Major (for Violin, Flute & Oboe), BWV 1049 4 I. Allegro 6. 38 5 II. Andante 3. 43 6 III. Presto 4. 28 Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major (For Trumpet, Flute, Oboe & Violin), BWV 1047 7 I. [Allegro] 4. 35 8 II. Andante 3. 46 9 III. Allegro assai 2. 41 Ana de la Vega, flute Ramón Ortega Quero, oboe Concerto for Two Violins (Flute & Oboe) in D Minor, BWV 1043 Alexander Sitkovetsky, violin 10 I. Vivace 3. 34 Johannes Berger, harpsichord 11 II. Largo ma non tanto 6. 15 Cyrus Allyar, trumpet 12 III. Allegro 4. 38 Württembergisches Kammerorchester Heilbronn The magnificent statue of J.S. Bach outside Yet when you come closer to the statue, one of his solos (likely from a draft version St. Thomas’s Church in Leipzig is, from you see that this man’s buttons are done of Cantata BWV 150). afar, everything we expect: arresting, up incorrectly. austere, and commanding. The godfather Let’s take the case of the Brandenburg of Western classical music tradition, the Standing under the great Carl Seffner Concertos: he wrote several of them master of perfection, precision and balance, statue in Leipzig, I felt I understood for starting c. -

BCAS 11803 Mar 2020 Program Rev3 28 Pages.Indd

ANTHONY BLAKE CLARK Music Director SUNDAY, MARCH 1, 2020 Baltimore Choral Arts Society Anthony Blake Clark 54th Season: 2019-20 Sunday, March 1, 2020 at 3 pm Shriver Hall Auditorium, The Johns Hopkins University, Homewood Campus Monteverdi Vespers Anthony Blake Clark, conductor Leo Wanenchak, associate conductor Baltimore Baroque Band, Peabody’s Baroque Orchestra, Dr. John Moran and Risa Browder, co-directors Peabody Renaissance Ensemble, Mark Cudek, director; Adam Pearl, choral coach Washington Cornett and Sackbutt Ensemble, Michael Holmes, director The Baltimore Choral Arts Chorus James Rouvelle and Lili Maya, artists Vespro della Beata Vergine Claudio Monteverdi I. Domine ad adiuvandum II. Dixit dominus III. Nigra sum IV. Laudate pueri V. Pulchra es VI. Laetatus sum VII. Duo seraphim VIII. Nisi dominus Intermission IX. Audi coelum X. Lauda Ierusalem XI. Sonata sopra Sancta Maria ora pro nobis XII. Ave maris stella XIII. Magnificat 2 Monteverdi Vespers is generously sponsored by the William G. Baker, Jr. Memorial Fund, creator of the Baker Artists Portfolios, www.BakerArtists.org. This performance is supported in part by the Maryland State Arts Council (msac.org). Our concerts are also made possible in part by the Citizens of Baltimore County and Mayor Jack Young and the Baltimore Offi ce of Promotion and the Arts. Our media sponsor for this performance is Please turn the pages quietly, and please turn off all electronic devices during the concert. The use of cameras and recording equipment is not allowed. Thanks for your cooperation. Please visit our web site: www.BaltimoreChoralArts.org e-mail: [email protected] 1316 Park Avenue | Baltimore, MD 21217 410-523-7070 Copyright © 2020 by the Baltimore Choral Arts Society Notice: Baltimore Choral Arts Society, Inc. -

March 2019 2 •

2018/19 Season January - March 2019 2 • This spring, two of today's greatest Lieder interpreters, the German baritone Christian Gerhaher and his regular pianist Gerold Huber, return to survey one of the summits of the repertoire, Schubert’s psychologically intense Winterreise. Harry Christophers and The Sixteen join us with a programme of odes, written to welcome Charles II back Director’s to London from his visits to Newmarket, alongside excerpts from Purcell's incidental music to Theodosius, Nathaniel Lee's 1680 tragedy. Introduction Leading Schubert interpreter Christian Zacharias delves into the composer’s unique melodic, harmonic and thematic flourishes in his lecture-recital. Through close examination of these musical hallmarks and idiosyncrasies, he takes us on a journey to the very essence of Schubert’s style. With her virtuosic ability to sing anything from new works to Baroque opera and Romantic Lieder with exceptional quality, Marlis Petersen is one of the most enterprising singers today. Her residency continues with two concerts, sharing the stage with fellow singers and accompanists of international acclaim. This year’s Wigmore Hall Learning festival, Sense of Home, celebrates the diversity and multicultural melting pot that is London and the borough of Westminster, reflects on Wigmore Hall as a place many call home, and invites you to explore what ‘home’ means to you. One of the most admired singers of the present day, Elīna Garanča, will open the 2018/19 season at the Metropolitan Opera as Dalila in Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila. Her programme in February – comprising four major cycles – includes Wagner's Wesendonck Lieder, two of which were identified by the composer himself as studies for Tristan und Isolde. -

Bach: the Master and His Milieu June 23-30, 2019

39th Annual Season Bach: The Master and His Milieu June 23-30, 2019 39th Annual Festival Bach: The Master and His Milieu Elizabeth Blumenstock, Artistic Director elcome to the 2019 edition of the Baroque Music Festival, Corona del WMar! Once again, we continue the tradition established by our founder, Burton Karson, of presenting five concerts over eight days. Violinist Elizabeth Blumenstock, now in her ninth year as artistic director, programmed her first “Bach-Fest” back in 2015, and this year she felt the time was right to revisit the concept: a week of glorious Bach, explored from many angles. Our Festival Finale has always been devoted to vocal masterpieces; this year the Wednesday program is too. And the “Milieu” of this season’s title will be explored through music by Bach’s influencers and contemporaries, creating a fascinating historical and musical journey. Thank you for being an integral part of this year’s Festival. We are grateful to you — our donors, foundation contributors, corporate partners, advertisers and concertgoers — for your ongoing and generous support. Festival Board of Directors Patricia Bril, President The Concerts Sunday, June 23 ..................Back to Bach Concertos ..........................8 Monday, June 24 ................Glories of the Guitar .............................14 Wednesday, June 26 ..........Passionate Voices ...................................18 Friday, June 28 ...................Bach’s Sons, Friends and Rivals ...........28 Sunday, June 30 ..................Bach the Magnificent ............................36 All concerts are preceded by brass music performed al fresco (see page 55) and followed by a complimentary wine & waters reception to which you are cordially invited to mingle with the performers. 3 M. & R. Weisshaar & Son Violin Shop, Inc. -

Sunday Playlist

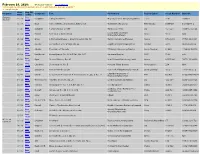

February 16, 2020: (Full-page version) Close Window “There was no one near to confuse me, so I was forced to become original.” — Joseph Haydn Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Buy 00:01 Corigliano Lullaby for Natalie Meyers/London Symphony/Slatkin e one 7791 099923 Awake! Now! Buy 00:07 Bach Cello Suite No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1008 Mstislav Rostropovich EMI Classics 55364/5 D 273269-1 Now! Buy 00:30 Schubert 4 Impromptus, D. 899 Maria Joao Pires DG 457 550 028945755021 Now! Buy Los Angeles Chamber 01:01 Handel Suite in G ~ Water Music Delos 3010 N/A Now! Orchestra/Schwarz Buy 01:12 Grieg 3 Orchestral Pieces ~ Sigurd Jorsalfar, Op. 56 Malmö Symphony/Engeset Naxos 8.508015 747313801534 Now! Buy 01:30 Dvorak Serenade in E for Strings, Op.22 English String Orch/Boughton Nimbus 5016 08360350162 Now! Buy 02:00 Sibelius The Swan of Tuonela Pittsburgh Symphony/Maazel Sony Classical 61963 074646196328 Now! Buy 02:13 Beethoven String Quartet No. 12 in E flat, Op. 127 Smetana Quartet PCM 7063 n/a Now! Buy 02:50 Elgar Dream Children, Op. 43 New Zealand Symphony/Judd Naxos 8.557166 747313216628 Now! Buy 03:00 Chadwick String Quartet No. 5 Portland String Quartet Northeastern 234 N/A Now! Buy 03:34 Strauss Jr. Roses from the South New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Sony Classical 46710 07464467102 Now! Buy Chamber Orchestra of 03:47 Vivaldi Concerto in B minor for 4 Violins and Cello, Op. 3 No. 10 EMI 69143 5099976914324 Now! Toulouse/Auriacombe Buy 04:01 Mendelssohn Hebrides Overture, Op. -

Download the 2016-2019 Strings Syllabus

Strings Syllabus Bowed Strings & Harp Grade exams 2016–2019 Trinity College London www.trinitycollege.com Charity number 1014792 Patron HRH The Duke of Kent KG Copyright © 2015 Trinity College London Published by Trinity College London Online edition, 12 March 2018 Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 3 Why take a Trinity grade exam? ........................................................................... 4 Range of qualifications ............................................................................................... 5 About this syllabus ....................................................................................................... 6 About the exam ............................................................................................................... 7 Exam structure and mark scheme.................................................................................... 7 Pieces......................................................................................................................................... 9 Own composition ................................................................................................................... 11 Mark scheme for pieces ......................................................................................................12 Technical work .......................................................................................................................13 Supporting -

PDF (Final Accepted Dissertation for MA by Thesis)

Durham E-Theses Neoclassicism in the Music of William Alwyn: Selected Works 1938-45 SWEET, ELIZABETH How to cite: SWEET, ELIZABETH (2016) Neoclassicism in the Music of William Alwyn: Selected Works 1938-45, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11796/ Use policy This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication 1.0 (CC0) Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Neoclassicism in the Music of William Alwyn Selected Works 1938-45 Elizabeth Sweet Neoclassicism in the Music of William Alwyn Elizabeth Sweet Material Abstract In 1938 William Alwyn made the radical decision to abandon his previous composition methods and based future works upon the neoclassical compositional aesthetic. The second work to emerge was the Divertimento for Solo Flute, a composition on a single stave with substantial implicit contrapuntal writing. This thesis will examine both the Continental European and British musical context in the period leading up to Alwyn’s 1938 compositional crisis in order to provide a model for neoclassicism. This model will be used to assess Alwyn’s neoclassical compositions to evaluate Alwyn as a composer in the light of his stated wish to become a Bach or Beethoven. It will also include a brief musical biography in order to contextualise Alwyn’s neoclassical compositions within the wider body of his work. i Neoclassicism in the Music of William Alwyn Selected Works 1938-45 Elizabeth Sweet Submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts by Research Department of Music University of Durham 2016 ii Contents INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................. -

Swingle Singers – Wikipedia Page 1 of 4

Swingle Singers – Wikipedia Page 1 of 4 Swingle Singers aus Wikipedia, der freien Enzyklopädie Die Swingle Singers sind ein professionelles A-cappella-Oktett, das in den 1960er-Jahren von dem US- Amerikaner Ward Swingle in Paris gegründet wurde. Der Name Swingle leitet sich ursprünglich vom deutschen Familiennamen Schwingel ab. Inhaltsverzeichnis ■ 1 Die Gruppe ■ 2 Geschichte ■ 2.1 Die Anfänge ■ 2.2 Die mittleren Jahre ■ 2.3 Bis heute ■ 3 Diskographie ■ 3.1 LPs ■ 3.2 CDs ■ 4 Literatur ■ 5 Weblinks Die Gruppe Das Ensemble aus sängerisch ausgebildeten Vollprofis gliedert sich in vier Frauen- und vier Männerstimmen, die mit leicht variierender Besetzung meist zwei Oberstimmen und eine Unterstimme bei den Frauen (Sopran I, Sopran II, und Alt) singen, und das analoge bei den Männerstimmen (Tenor I, Tenor II, und Bass). Die Swingle Singers singen praktisch immer mit Verstärkungstechnik, um die leise intonierten, schnellen und hochpräzisen Stimmen für das Publikum gut hörbar zu machen. Die Swingle Singers zeichnen sich aus durch eine enorm leichte, flexible, schnelle und präzise Intonation und Stimmführung. Sie wurden weltberühmt, als sie sich mit klassischer Musik befassten und Stücke von Komponisten wie Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart und Johann Sebastian Bach, unterlegt mit Silben des Scat-Gesanges, ohne begleitende Instrumente darboten. Sie zählen zusammen mit den englischen King’s Singers zu den weltbesten professionellen A-cappella-Ensembles. Bis heute traten die Swingle Singers weltweit in über 3000 Konzerten auf und veröffentlichten über 40 Tonträger. Geschichte http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swingle_Singers 16.09.2009 Swingle Singers – Wikipedia Page 2 of 4 Die Anfänge Vorläufer der Gruppe waren die französischen Vokalensembles Blue Stars unter der Leitung von Blossom Dearie und Les Double Six unter Leitung von Mimi Perrin, die auch mit Quincy Jones zusammengearbeitet hatten. -

Yuan Sheng Piano JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750)

Bach J.S.BACH Complete Partitas KEYBOARD WORKS VOLUME 2 Yuan Sheng piano JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750) Partita No. 1 in B-Flat Major, Partita No.3 in A Minor, BWV 827 Bach at 40 BWV 825 20. Fantasia 2’08 In 1725 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) was a middle-aged man with 1. Praeludium 1’46 21. Allemande 2’46 an important position since 1723 as Cantor of the legendary choir school of 2. Allemande 3’51 22. Corrente 3’25 St. Thomas Church in Leipzig. He had a formidable reputation as a brilliant 3. Corrente 2’57 23. Sarabande 4’38 keyboardist and an impressive body of compositions, sacred and secular, 4. Sarabande 5’35 24. Burlesca 2’17 for keyboard, chamber ensembles, and orchestra as well as voices. Yet, 5. Menuet I&II 3’09 25. Scherzo 1’10 unlike his most eminent contemporaries with international reputations 6. Giga 2’02 26. Gigue 3’15 (such Handel and Telemann, François Couperin and Rameau, and Corelli, Torelli, and Vivaldi, to name some whose work was known to Bach), Partita No.2 in C Minor, BWV 826 Partita No.5 in G Major, BWV 829 Bach’s music—because it was not published--was essentially unknown 7. Sinfonia 4’16 27. Praeambulum 2’38 beyond the immediate circle of his family, students, and colleagues, or the 8. Allemande 4’37 28. Allemande 4’20 congregations who heard his church music. By 1725, this included not only 9. Courante 2’21 29. Corrente 1’50 most of the keyboard music familiar today—the English and French Suites, 10. -

Mendelssohn's Reformation Symphony

TAMPA BAY TIMES MASTERWORKS Mendelssohn’s Reformation Symphony Jan 9 & 10, 2021 JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750) FUGA (No. 2 “RICERCATA”) from the MUSICAL OFFERING, BWV 1079 In one of the more intriguing Masterworks programs of the season, TFO devotes the weekend to a musical offering of rarities, including a symphony based on a theme going back to the early 1500s and a baroque keyboard tune dressed in modern clothing. The tune – a six-part fugue by Johann Sebastian Bach – comes from a collection of pieces he composed in 1747 known as the Musical Offering. This “offering’’ is based on Bach’s improvisation on a theme presented to him by Frederick the Great, an amateur musician whom Bach visited toward the end of his life. He ad- libbed a three-part fugue on the spot, then later set to work on a more complex variation that the musicol- ogist Charles Rosen called “Bach’s greatest fugue.’’ Not stopping there, Bach fleshed out a number of other pieces to accompany Frederick’s “royal’’ theme, bound the score in leather and sent it to the Prussian king as a gift. The fugue is known as a ricercar, an ancient musical term that means “to search out.’’ Intricate and serious in mood, it unfolds in six separate but related lines, which together are nearly impossible to play with two hands on a keyboard – whether organ, harpsichord or piano. Historians for two centuries have pondered why Bach composed something so problematic; maybe he just wanted a good brain teaser. The music features prominently in Douglas Hofstadter’s 1979 Pulitzer Prize-winning book Gödel, Escher, Bach, and made an impression on Anton Webern, who in 1935 arranged it for small orchestra. -

Download Booklet

J.S. Bach CIACCONACIACCONA Bin Hu guitar To my father 01. Prelude, from the Partita BWV 1006 ............................... 04:21 Sonata BWV 1001 02. I. Adagio ................................................................................ 03:45 03. II. Fuga. Allegro .................................................................... 05:24 04. III. Siciliana .......................................................................... 02:40 05. IV. Presto ............................................................................... 04:37 Sonata BWV 1003 06. I. Grave ................................................................................. 04:07 07. II. Fuga .................................................................................. 07:22 08. III. Andante .......................................................................... 05:09 09. IV. Allegro ............................................................................. 06:18 10. Chaconne, from the Partita BWV 1004 ............................. 14:31 total time 11. Sinfonia BWV 156 ............................................................. 04:03 62:24 Ciaccona Kathy Acosta Zavala & Bin Hu Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) ince the rediscovery of Johann Sebastian Bach’s works in the first half of the 19th century, Sa musical phenomenon known as the «Bach Revival,»1 musicians of all instruments have 04 05 included Bach’s works in their repertoires as technical, musical and artistic proving tools to showcase their instruments’ capabilities. The guitar has been no