Cello Evolutions II: Laurence Lesser, Cello

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: a Study of Traditions and Influences

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2012 Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences Sara Gardner Birnbaum University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Birnbaum, Sara Gardner, "Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences" (2012). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 7. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/7 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

Guest Artist Cello Concert Bryan Hayslett

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Guest Artist Cello Concert Bryan Hayslett Tuesday, October 28, 2014 • 7:30 p.m. Belhaven University Center for the Arts • Concert Hall There will be a reception after the program. Please come and greet the performer. Please refrain from the use of all flash and still photography during the concert. Please turn off all pagers and cell phones. PROGRAM Please hold applause until intermission. Cello Suite No. 6 in D Major, BWV 1012 Johann Sebastian Bach • 1685 - 1750 I. Prelude Unlocked, 1. Make Me a Garment Judith Weir • b. 1954 Unlocked, 2. No Justice A Portrait in Greys Marissa Deitz Wall • b. 1990 Suite No. 6, 2. Allemande J.S. Bach Suite No. 6, 3. Courante Age of the Deceased (Six Months in Chicago) Drew Baker • b. 1978 INTERMISSION Suite No. 6, 4. Sarabande J.S. Bach Suite No. 6, 5. Gavotte A Portrait in Greys Keith Kusterer • b. 1981 Unlocked, 5. Trouble, trouble Judith Weir Suite No. 6, 6. Gigue J.S. Bach A Portrait in Greys by William Carlos Williams Will it never be possible to separate you from your greyness? Must you be always sinking backward into your grey-brown landscapes— And trees always in the distance, always against a grey sky? Must I be always moving counter to you? Is there no place where we can be at peace together and the motion of our drawing apart be altogether taken up? I see myself standing upon your shoulders touching a grey, broken sky— but you, weighted down with me, yet gripping my ankles,—move laboriously on, where it is level and undisturbed by colors. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

Proquest Dissertations

Benjamin Britten's Nocturnal, Op. 70 for guitar: A novel approach to program music and variation structure Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alcaraz, Roberto Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 13:06:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/279989 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be f^ any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitlsd. Brolcen or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author dkl not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectk)ning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additkxial charge. -

Download Booklet

Charming Cello BEST LOVED GABRIEL SCHWABE © HNH International Ltd 8.578173 classical cello music Charming Cello the 20th century. His Sérénade espagnole decisive influence on Stravinsky, starting a Best loved classical cello music uses a harp and plucked strings in its substantial neo-Classical period in his writing. A timeless collection of cello music by some of the world’s greatest composers – orchestration, evoking Spain in what might including Beethoven, Haydn, Schubert, Vivaldi and others. have been a recollection of Glazunov’s visit 16 Goodall: And the Bridge is Love (excerpt) to that country in 1884. ‘And the Bridge is Love’ is a quotation from Thornton Wilder’s novel The Bridge of 1 6 Johann Sebastian BACH (1685–1750) Franz Joseph HAYDN (1732–1809) 14 Ravel: Pièce en forme de habanera San Luis Rey which won the Pulitzer Prize Bach: Cello Suite No. 1 in G major, 2:29 Cello Concerto in C major, 9:03 (arr. P. Bazelaire) in 1928. It tells the story of the collapse BWV 1007 – I. Prelude Hob.VIIb:1 – I. Moderato Swiss by paternal ancestry and Basque in 1714 of ‘the finest bridge in all Peru’, Csaba Onczay (8.550677) Maria Kliegel • Cologne Chamber Orchestra through his mother, Maurice Ravel combined killing five people, and is a parable of the Helmut Müller-Brühl (8.555041) 2 Camille SAINT-SAËNS (1835–1921) his two lineages in a synthesis that became struggle to find meaning in chance and in Le Carnaval des animaux – 3:07 7 Robert SCHUMANN (1810–1856) quintessentially French. His Habanera, inexplicable tragedy. -

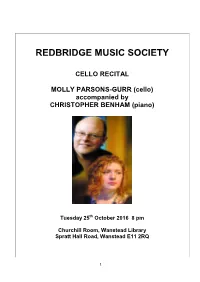

Molly Parson-Gurr Recital Programme 25 Oct 2016

REDBRIDGE MUSIC SOCIETY CELLO RECITAL MOLLY PARSONS-GURR (cello) accompanied by CHRISTOPHER BENHAM (piano) Tuesday 25th October 2016 8 pm Churchill Room, Wanstead Library Spratt Hall Road, Wanstead E11 2RQ 1 PROGRAMME ‘Arioso’ for cello and piano J S Bach (1685 – 1750) Suite No. 1 in G major for solo cello BWV 1007 J S Bach (1685 – 1750) i Prelude ii Allemande iii Courante iv Sarabande v Minuets 1 & 2 vi Gigue Drei Fantasiestücke for cello and piano Op. 73 Robert Schumann (1810 - 1856) i Zart und mit Ausdruck (Tender and with expression) ii Lebhaft, leicht (Lively, light) iii Rasch und mit Feuer (Quick and with fire) INTERVAL Sonata in G minor for Cello and Piano Op 19 Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873 – 1943) i Lento – Allegro moderato ii Allegro scherzando iii Andante iv Allegro mosso PROGRAMME NOTES J S Bach: Arioso for cello and piano & Suite No. 1 in G major for solo cello BWV 1007 The ‘arioso’ you will hear at this evening’s recital is an arrangement for cello and piano of the sinfonia which opens Bach’s church Cantata "Ich steh`mit einem Fuss im Grabe" (“I am standing with one foot in the grave”) BWV 156 first performed in Leipzig in 1729. The original sinfonia was scored for oboe, strings and continuo and was most likely derived from an early F major oboe concerto of Bach’s; it appears also as the middle movement (largo) of Bach’s Harpsichord Concerto No.5 in F minor BWV 1056. There have been many arrangements of the ‘arioso’ including those for trumpet and piano, violin and piano, solo guitar and also for full orchestra (the latter arr. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

Bach Unbuttoned

Bach Unbuttoned ANA DE LA VEGA ALEXANDER SITKOVETSKY · RAMÓN ORTEGA QUERO CYRUS ALLYAR · JOHANNES BERGER WÜRTTEMBERGISCHES KAMMERORCHESTER HEILBRONN Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Suite No. 2 in B Minor (For Flute, Strings & Basso Continuo), BWV 1067 13 VII. Badinerie 1. 24 Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D Major (for Flute, Violin & Harpsichord), BWV 1050 Total playing time: 62. 26 1 I. Allegro 9. 22 2 II. Affetuoso 5. 54 3 III. Allegro 5. 11 Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 in G Major (for Violin, Flute & Oboe), BWV 1049 4 I. Allegro 6. 38 5 II. Andante 3. 43 6 III. Presto 4. 28 Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major (For Trumpet, Flute, Oboe & Violin), BWV 1047 7 I. [Allegro] 4. 35 8 II. Andante 3. 46 9 III. Allegro assai 2. 41 Ana de la Vega, flute Ramón Ortega Quero, oboe Concerto for Two Violins (Flute & Oboe) in D Minor, BWV 1043 Alexander Sitkovetsky, violin 10 I. Vivace 3. 34 Johannes Berger, harpsichord 11 II. Largo ma non tanto 6. 15 Cyrus Allyar, trumpet 12 III. Allegro 4. 38 Württembergisches Kammerorchester Heilbronn The magnificent statue of J.S. Bach outside Yet when you come closer to the statue, one of his solos (likely from a draft version St. Thomas’s Church in Leipzig is, from you see that this man’s buttons are done of Cantata BWV 150). afar, everything we expect: arresting, up incorrectly. austere, and commanding. The godfather Let’s take the case of the Brandenburg of Western classical music tradition, the Standing under the great Carl Seffner Concertos: he wrote several of them master of perfection, precision and balance, statue in Leipzig, I felt I understood for starting c. -

Light & Matter

THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO fUND fOR nEW mUSIC LIGHT & MATTER JENNIFER KOH, vIOLIN ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cELLO IEVA JOKUBAVICIUTE, pIANO Friday, May 22, 2015 ~ 8 pm Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC Endowed by the late composer and pianist Dina Koston (1929-2009) and her husband, prominent Washington psychiatrist Roger L. Shapiro (1927-2002), the DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC supports commissions, contemporary music and its performers. Presented in association with the European Month of Culture Part of National Chamber Music Month Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. • Please take note: Unauthorized use of photographic and sound recording equipment is strictly prohibited. Patrons are requested to turn off their cellular phones, alarm watches, and any other noise-making devices that would disrupt the performance. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. The Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium Friday, May 22, 2015 — 8 pm THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO fUND fOR nEW mUSIC LIGHT & MATTER JENNIFER KOH, vIOLIN ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cELLO IEVA JOKUBAVICIUTE, pIANO • Program CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862–1918) Sonate pour Violoncelle et Piano (1915) Prologue: Lent, Sostenuto e molto risoluto–(Agitato)–au Mouvt (largement déclamé)–Rubato–au Mouvt (poco animando)–Lento Sérénade: Modérément animé–Fuoco–Mouvt–Vivace–Meno mosso poco– Rubato–Presque lent–1er Mouvt–au Mouvt– Finale: Animé, Léger et nerveux–Rubato–1er Mouvt–Con fuoco ed appassionato–Lento. -

BCAS 11803 Mar 2020 Program Rev3 28 Pages.Indd

ANTHONY BLAKE CLARK Music Director SUNDAY, MARCH 1, 2020 Baltimore Choral Arts Society Anthony Blake Clark 54th Season: 2019-20 Sunday, March 1, 2020 at 3 pm Shriver Hall Auditorium, The Johns Hopkins University, Homewood Campus Monteverdi Vespers Anthony Blake Clark, conductor Leo Wanenchak, associate conductor Baltimore Baroque Band, Peabody’s Baroque Orchestra, Dr. John Moran and Risa Browder, co-directors Peabody Renaissance Ensemble, Mark Cudek, director; Adam Pearl, choral coach Washington Cornett and Sackbutt Ensemble, Michael Holmes, director The Baltimore Choral Arts Chorus James Rouvelle and Lili Maya, artists Vespro della Beata Vergine Claudio Monteverdi I. Domine ad adiuvandum II. Dixit dominus III. Nigra sum IV. Laudate pueri V. Pulchra es VI. Laetatus sum VII. Duo seraphim VIII. Nisi dominus Intermission IX. Audi coelum X. Lauda Ierusalem XI. Sonata sopra Sancta Maria ora pro nobis XII. Ave maris stella XIII. Magnificat 2 Monteverdi Vespers is generously sponsored by the William G. Baker, Jr. Memorial Fund, creator of the Baker Artists Portfolios, www.BakerArtists.org. This performance is supported in part by the Maryland State Arts Council (msac.org). Our concerts are also made possible in part by the Citizens of Baltimore County and Mayor Jack Young and the Baltimore Offi ce of Promotion and the Arts. Our media sponsor for this performance is Please turn the pages quietly, and please turn off all electronic devices during the concert. The use of cameras and recording equipment is not allowed. Thanks for your cooperation. Please visit our web site: www.BaltimoreChoralArts.org e-mail: [email protected] 1316 Park Avenue | Baltimore, MD 21217 410-523-7070 Copyright © 2020 by the Baltimore Choral Arts Society Notice: Baltimore Choral Arts Society, Inc. -

Zi-Yun Luo, Cello

Presents Artist Diploma Recital Zi-Yun Luo, Cello March 29th, 2021 05:30PM Taipei, Taiwan Program Solo Cello Suite in D minor No.2, Op. 131c Max Reger (1873-1916) Prelude, Largo Gavotte, Allegretto Largo Gigue, Vivace Solo Cello Suite No.1, Op.72 Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) Canto primo (sostenuto e largamente) Fuga, Andante moderato Lamento, Lento rubato Canto secondo (sostenuto) Serenata, Allegretto pizzicato Marcia, Alla marcia moderato Canto terzo (sostenuto) Bordone, Moderato quasi recitativo Moto perpetuo e canto quarto, presto This recital is given in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Artist Diploma in Cello Performance Zi-Yun Luo is a student of Dr. Jesús Castro-Balbi Program Note Solo Cello Suite in D minor No.2, Op. 131c Max Reger (1873-1916) Suite No 2 in D minor (dedicated, like the Cello Sonata No 2, to Hugo Becker) begins with one of Reger’s finest cello inspirations, a Präludium of impassioned sorrow whose Bachian models are transcended in a remarkable display of empathy with the inmost soul of the instrument. Elegiac meditation is the tone throughout, even in the somewhat more virtuosic central section. Reger’s command of a beautiful and flexible ‘speaking’ single line is nowhere better demonstrated. After its eloquent final climax the music subsides swiftly and sadly to a hushed ppp ending. In strong contrast, the succeeding movement is a cheerful Gavotte in F major, very formal in its layout and proportions. The central section makes both witty and poetic use of the alternation of arco and pizzicato playing. The Largo third movement is a deeply expressive and rather melancholic soliloquy in B flat major, its chaste single line progressively reinforced by plangent double-stopping and more rapid scalic passages. -

David Finckel, Cello Wu Han, Piano

Sunday, November 24, 2019, 3pm Hertz Hall David Finckel, cello Wu Han, piano PROGRAM Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770–1827) Cello Sonata No. 3 in A major, Op. 69 Allegro ma non tanto Scherzo: Allegro molto Adagio cantabile – Allegro vivace Johannes BRAHMS (1833–1897) Cello Sonata No. 2 in F major, Op. 99 Allegro vivace Adagio affettuoso Allegro passionato – Trio Allegro molto INTERMISSION Claude DEBUSSY (1862–1918) Nocturne and Scherzo for Cello and Piano César FRANCK (1822–1890) Violin Sonata in A Major (trans. cello) Allegro ben moderato Allegro Recitativo-fantasia (Ben moderato – Molto lento) Allegretto poco mosso David Finckel and Wu Han appear by arrangement with David Rowe Artists (www.davidroweartists.com). Public Relations and Press Representative: Milina Barry PR (www.milinabarrypr.com) David Finckel and Wu Han recordings are available exclusively through ArtistLed (www.artistled.com). Artist website: www.davidfinckelandwuhan.com Wu Han performs on the Steinway Piano. This performance is made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsors Will and Linda Schieber. Cal Performances’ 2019–20 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 21 PROGRAM NOTES Ludwig van Beethoven The cello and piano continue trading motifs, Cello Sonata No. 3 in A major, Op. 69 each repeating what the other has just played. Beethoven composed the Sonata in A major— A heroic closing theme is the culmination of one of the greatest works in the cello litera- the section and a brief, contemplative recollec- ture—between 1807 and 1808, in the midst of tion of the opening motif leads to the repeat one of his most phenomenally prolific periods of the exposition.