International Sanctions and the Survival of Authoritarian Rulers1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mckee, Alan (1996) Making Race Mean : the Limits of Interpretation in the Case of Australian Aboriginality in Films and Television Programs

McKee, Alan (1996) Making race mean : the limits of interpretation in the case of Australian Aboriginality in films and television programs. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4783/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Making Race Mean The limits of interpretation in the case of Australian Aboriginality in films and television programs by Alan McKee (M.A.Hons.) Dissertation presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Glasgow in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Glasgow March 1996 Page 2 Abstract Academic work on Aboriginality in popular media has, understandably, been largely written in defensive registers. Aware of horrendous histories of Aboriginal murder, dispossession and pitying understanding at the hands of settlers, writers are worried about the effects of raced representation; and are always concerned to identify those texts which might be labelled racist. In order to make such a search meaningful, though, it is necessary to take as axiomatic certain propositions about the functioning of films: that they 'mean' in particular and stable ways, for example; and that sophisticated reading strategies can fully account for the possible ways a film interacts with audiences. -

No. 22731 ••••••••••••••••••••• 1 Oktober 2 No

Vol. 436 Pretoria, 12 October 2001 No. 22731 ••••••••••••••••••••• 1 Oktober 2 No. 22731 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 12 OCTOBER 2001 For purposes 01 reference, all Proclamations, Govemment Aile Proldamasies, Goewermenlskennisgewings, Aigemene Notices, General Notices and Board Notices pubUshed s,. Kennlsgewlngs en Raadskennlsgewlngs gepubllseer, word vir Included In the following table of contanla which thus fonna a verwyBlngsdoelelndes In die volgende InhoudsopgBwe Inge- weekly Index. Let yourself bs gUided by the G_numbs.. In alult wat dus 'n weekllkse Indeks voorstel. Laat uself deur die the rlghthand column: Koerantnommers In die regterhandse kolom lei: CONTENTS INHOUD and weekly Index en weeklikse Indeks psga Gazalfa Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. GOVERNMENT AND GENERAL NOTICES GOEWERMENTS- EN ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS Arbeld, Departement van Agriculture, Department of Goewermentskennisgewings GovernmentNotice 962 Compensation for Occupational Injuries R. 964 Fertilizers, Farm Feeds, Agricultural and Diseases Act (130/1993): Increase Remedies and Stock Remedies Act in monthly pensions: Amendment . 3 22721 (36/1947): Regulations: Registration of fertilizers, farm feeds, agricultural reme 963 do.: Amendment of Schedule 4 . 5 22721 dies, stock remedies, sterilising plants AlgemeneKennisgewing and pest control operators, appeals and imports:Amendment . 3 22714 2114 Labour Relations Act (66/1995): Com mission for Conciliation Mediation and General Notices Arbitration: Notice in terms of section 2118 Agricultural Product Standards Act 62 (7)................. .. 3 22730 (119/1990): Standards and requir.m.nts regarding control of the export01 melons Behulslng, Departement van and watermelons: Amendment . 70 22731 AigemeneKennisgewing 2127 Marketing of Agricultural Products Act (47/1996): Request for statutory 2112 Explanatory summary of Disestablish measures on potatoes . 74 22731 ment of South African Housing Trust Limited Bill, 2001 . -

35692 21-9 Legalap1 Layout 1

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA Vol. 567 Pretoria, 21 September 2012 No. 35692 PART 1 OF 2 LEGAL NOTICES A WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure G12-094626—A 35692—1 2 No. 35692 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 21 SEPTEMBER 2012 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. TABLE OF CONTENTS LEGAL NOTICES Page BUSINESS NOTICES.............................................................................................................................................. 11 Gauteng..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Eastern Cape............................................................................................................................................ -

The Parliament Lock, Stock and Barrel Tons of Carbon Dioxide, the Equivalent of on the Eurosceptic Side of the Party Than to Strasbourg One Week a Month

Issue 258 10 December 2007 FREE INSIDE: Treaty talk with parliament’s group SLOVENIAN EU PRESIDENCY leaders: PULL-OUT GUIDE Joseph Daul Martin Schulz Graham Watson Monica Frassoni Playing its part HANS-GERT PÖTTERING ON THE NEW LISBON TREATY “THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT CAN FINALLY TAKE ITS PLACE AS THE GENUINE JOINT LEGISLATURE OF A DEMOCRATIC EU” GOING GREEN PLUS Andris Piebalgs EU-Africa summit Alejo Vidal-Quadras Consumer safety Gabriele Albertini CAP reform Jacqueline McGlade MEP profile: Jens Hügel Jorgo Chatzimarkakis ������ ���������������������������������� Microsoft® gives Tablet PCs, teacher� and student training, and software� to schools. By providing state of the art educational tools, it helps teachers teach and children gain the skills they’ll need to reach their potential. Find out more at www.microsoft.com/potential © 2006 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved. Microsoft and “Your potential. Our passion.” are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. 1403_M_kid_EN_270x210.indd 1 9/18/07 6:09:25 PM Issue 258 10 December 2007 Editor’s comment the world politicians and Knowledge is power and the EU is not the only governments are pondering country recognising the need to educate and Globalisation never disappears from how to help those who skill its workforce. China has now introduced the political agenda although the word have lost out in this rapid a policy of free school education not just means different things to different time of change. In Europe for nine years but for twelve years. China’s people. It is hard to come up with losers include unskilled universities are charging tuition fees and China a definition that truly encapsulates workers, and in China and is set to produce more engineering graduates its meaning. -

Descriptions of New Species of the Diverse and Endemic Land Snail

© The Author, 2011. Journal compilation © Australian Museum, Sydney, 2011 Records of the Australian Museum (2011) Vol. 63: 167–202. ISSN 0067-1975 doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.63.2011.1581 Descriptions of New Species of the Diverse and Endemic Land Snail Amplirhagada Iredale, 1933 from Rainforest Patches across the Kimberley, Western Australia (Pulmonata: Camaenidae) Frank köhler Department of Environment and Conservation of Western Australia, Science Division, Wildlife Place, Woodvale WA 6026, Australia and Australian Museum, 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia [email protected] abstract. Fifteen species of the camaenid land snail Amplirhagada, which are endemic to the Kimberley region in Western Australia, are newly described in the present work based on material collected in 1987 during the Kimberley Rainforest Survey of the then Dept. Conservation and Land Management, Western Australia. These species were listed previously as new discoveries under preliminary species identifications but have never been validly described. All of them were collected in rainforest and vine thicket patches across the Kimberley, where they generally occur as narrow-range endemics. The species are most typically characterized by a peculiar penial anatomy while other morphological structures, such as the shell or radula, provide characters less or not suitable for unambiguous species identification. Three manuscript taxa listed as potentially new are here preliminarily subsumed under an already described taxon, A. carinata Solem, 1981. By contrast to all other species treated herein, A. carinata has a fairly large distribution around the Walcott Inlet in the Southwest Kimberley. This taxon also reveals a comparatively large amount of morphological variation not only with respect to the shell but also to its genital anatomy. -

Making the Right Moves a Practical Guide to Scientifıc Management for Postdocs and New Faculty

Making the Right Moves A Practical Guide to Scientifıc Management for Postdocs and New Faculty Burroughs Wellcome Fund Howard Hughes Medical Institute Second Edition Making the Right Moves A Practical Guide to Scientifıc Management for Postdocs and New Faculty Second Edition Based on the BWF-HHMI Course in Scientifıc Management for the Beginning Academic Investigator Burroughs Wellcome Fund Howard Hughes Medical Institute Research Triangle Park, North Carolina Chevy Chase, Maryland © 2006 by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Burroughs Wellcome Fund All rights reserved. 09 08 07 06 1 2 3 4 5 Permission to use, copy, and distribute this manual or excerpts from this manual is granted provided that (1) the copyright notice above appears in all reproductions; (2) use is for noncommercial educational purposes only; (3) the manual or excerpts are not modified in any way; and (4) no figures or graphic images are used, copied, or distrib- uted separate from accompanying text. Requests beyond that scope should be directed to [email protected]. The views expressed in this publication are those of its contributors and do not neces- sarily reflect the views of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute or the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. This manual is also available online at http://www.hhmi.org/labmanagement. Project Developers: Maryrose Franko, Ph.D., and Martin Ionescu-Pioggia, Ph.D. Editor: Laura Bonetta, Ph.D. Managing Editor: Patricia Davenport Production Manager: Dean Trackman Designer: Raw Sienna Digital Writers: Joan Guberman, Judith Saks, Barbara Shapiro, and Marion Torchia Copyeditors: Cay Butler and Kathleen Savory Indexer: Mary E. Coe Burroughs Wellcome Fund Howard Hughes Medical Institute 21 T.W.Alexander Drive 4000 Jones Bridge Road P.O. -

Ichthys Project Gas Export Pipeline (Operation) Environment Plan Summary

ICHTHYS PROJECT GAS EXPORT PIPELINE (OPERATION) ENVIRONMENT PLAN SUMMARY EP Summary Document No.: F075-AH-PLN-10004 Security Classification: Public Ichthys Project Gas Export Pipeline (Operation) Environment Plan Summary Document distribution Copy Name Hard Electronic no. copy copy 00 Document control 01 NOPSEMA Notice All information contained with this document has been classified by INPEX as Public and must only be used in accordance with that classification. Any use contrary to this document's classification may expose the recipient and subsequent user(s) to legal action. If you are unsure of restrictions on use imposed by the classification of this document you must refer to the INPEX Sensitive Information Protection Standard or seek clarification from INPEX. Uncontrolled when printed. Document no.: F075-AH-PLN-10004 Security Classification: Public Revision: 0 Date: 30 January 2017 Ichthys Project Gas Export Pipeline (Operation) Environment Plan Summary Table of contents 1 INTRODUCTION 11 1.1 Background 11 1.2 Activity overview 12 1.3 Titleholder’s details and nominated liaison person 14 2 DESCRIPTION OF ACTIVITY 15 2.1 Commencement 15 2.1.1 Start-up stage 15 2.1.2 Operations stage 15 2.2 Activities 15 2.2.1 Transfer of GEP gas through the GEP 15 2.2.2 Inspection, maintenance and repair (IMR) activities 17 2.2.3 Vessel activities 20 3 EXISTING ENVIRONMENT 21 3.1 Physical environment 21 3.2 Biological environment 24 3.2.1 Benthic habitats and communities 24 3.2.2 Shoreline habitats 29 3.2.3 Marine fauna 29 3.3 Socioeconomic and cultural -

Woody's Women Erotic Iction from FARROW to FOSTER

Game for a lay? AR! UM' LOOS MOWN SIXCESS? COMMIE MUM FAO 17 Incorporating magazine Britain's biggest weekly student newspaper May 3, 1996 Woody's women erotic iction FROM FARROW TO FOSTER. KEATON TO SORVINO - 1' IS IT ART OR AN OLD MAN'S FANTASY? The Juicy guide la the hottest juice: Pages 2.3 titles oa the literary top shell BODY FOUND BY SECURITY OUTSIDE LECTURE THEATRES Death on campus shocks university B CATRIONA DAVIES eNt. TIM GALLAGHER THE discovery of a dead finalist on campus has stunned students and staff at ALL ACTION BRINGS ALL SMILES Leeds University. The body of Alan Jackson. a third year Genetics student. was found behind the Roger Stevens building shortly before 7am on WednesdaN morning, 1-k is thought to have jumped from the window of a walkway 60 rect above the lecture theatre courtyard. The corridor. on level 10. connects the Genetics and Biochemistry departments. A window was later found open on the corridor. Security guards immediately called an ambulance. but on its arrival. Jackson. 21_ was found to be dead. Coroners have not yet confirmed the cha se of death, but police are not looking for anyone else in connection with the incident. A member of university staff. who was there before the police arrived. described the scene: "There was quite a lot of blood around the hotly. Some of the paving stones were smashed where he had fallen." Students on their way to lectures looked on as police removed the body in a bag at around 9am. A spokesman for the university said: "Alan was a hard working and well liked student who was doing well on his course and was expected to go on to postgraduate study The university extends ils deepest sympathies to his family." Counselling staff at Leeds University are providing a special session for distressed students from ..trim toda ■in Clarendon Road ilffiee_ SCENE OF THE INCIDENT: The spot outside the Roger Stevens building where the body was HAPPY HOLIDAY: Kids from Leeds enjoy the high life during a recent holiday in found Pic: Paul Shelley Durham, overseen by volunteers from Student Community Action. -

Kimberley Joseph

KIMBERLEY JOSEPH TRAINING Jessica Drake (Voice), Larry Moss (Accent & Voice), Atlantic Theatre Company 1999 FILM & TELEVISION FICKLE BICKLE (Short) Role: Jenny Bickle Dir: Stephen Ward, 2016 LOST (Series 6) Role: Cindy Chandler (Regular Cast) Dir: Various, ABC 2010 FROST/NIXON Role: Evonne Goolagong Dir: Ron Howard, Universal 2007 LOST (Series 3) Role: Cindy Chandler (Regular Cast) Dir: Various, ABC 2007 LOST (Series 1) Role: Cindy Chandler (Regular Cast) Dir: Various, ABC 2004 GO BIG (Telemovie) Role: Sophie Duvet (Leading Role) Dir: Tony Tilse, RB Films/ Network Ten 2004 ALL SAINTS Role: Grace Connolly (Semi-Regular) Dir: Various, Seven Network 2004 COLD FEET (Series 5) Role: Jo Ellison (Lead) Dir: Various, Granada TV UK 2003 COLD FEET (Series 4) Role: Jo Ellison (Lead) Dir: Various, Granada TV UK 2001 MURDER CALL Role: Andrea Thatcher (Guest) Dir: Steve Mann, Nine Network 2000 TALES OF THE SOUTH SEAS Role: Clare Devon (Lead) Dir: Various, Village Roadshow 2000 HERCULES: The Legendary Journeys (Series 6) Role: Nemesis Dir: Bruce Campbell, Pacific Renaissance Ltd 1999 WATER RATS Role: Mary Worth Dir: Mark Piper, Nine Network 1999 HERCULES: The Legendary Journeys (Series 4) Role: Nemesis Dir: Chris Graves, Pacific Renaissance Ltd 1997 FLIPPER Role: Vicki Village Roadshow Productions TV HOME & AWAY Role: Jo Brennan Dir: Various, Amalgamated TV 1995/1996 PARADISE BEACH (Series 2) Role: Cassie Barsby (Lead) Dir: Various, Village Roadshow 1994 PARADISE BEACH (Series 1) Role: Cassie Barsby (Lead) Dir: Various, Village Roadshow 1993 PRESENTING RESTORED Guest Designer DIY Network E NEWS! Hollywood Reporter Network Ten Australia THE BEST OF GLADIATORS – series one Co-Host Seven Network Australia GLADIATORS Co-Host Seven Network Australia HEY HEY IT’S SATURDAY Roving Reporter Nine Network Australia SALE OF THE CENTURY Co-Host Grundy Organisation / Nine Network Australia AXN TV EXTREME SPORTS Host Network Ten Australia . -

“For Governor Schwarzenegger Joining

Issue 257 26 November 2007 California’sCalifornia’s Linda Adams and Mary Nichols on how the Golden State is set to tackle climate change both at home and abroad California INSIDE dreaming The road to Bali: “FOR GOVERNORGOVERNOR SCHWARZENEGGERSCHWARZENEGGER JOININGJOINING Guido Sacconi Karl-Heinz Florenz ICAP IS AN IMPORTANT STEP FORWARD IN THE Katerina Batzeli STATE’S EFFORTS TO FIGHT GLOBAL WARMING” Roger Helmer World Aids Day ALCOHOL: EU-India László Kovács Eurostar Alessandro Foglietta Joaquín Almunia Richard Corbett on the global Alexander Stubb credit squeeze Catherine Stihler Issue 257 26 November 2007 Editor’s comment organisation which would (UNAIDS), almost half of all adults living associate itself with such with HIV in the world today are women. The fight against HIV/Aids is one a topic, yet it is this very WAGGGS has introduced practical that affects people across the world. organisation that is taking programmes that encourage young people to On world Aids day it is important to the lead in the fight against take part in projects and activities to prevent reflect on the challenges and solutions. HIV/Aids in 144 countries the spread of HIV/Aids through change in Even the European commission admits across the world. behaviour; to provide care and support for people that not enough is being done to The aim is “not only to who are living with HIV and Aids; and to fight promote prevention. speak out on behalf of fear, shame and injustice showing innovation, A recent lunch time seminar held in girls and young women vision, perseverance and leadership in the face of the European parliament had representatives everywhere, but also to empower young this challenge. -

St Hilda's Marks New Era in Tennis

Spirit ST HILDA’S SCHOOL, GOLD COAST ST HILDA’S SCHOOL OLD GIRLS’ ASSOCIATION September 2014 Volume 17 Issue 2 St Hilda’s marks new era in tennis Sylvia Alexander (nee Gibson 1980), Margaret (Margot) Lockhart Gibson (nee Dulhunty 1945), Head of School Mr Peter Crawley, Julia Crombie (1963) and Margaret Brown (nee Crombie 1963) at the official opening of the Turbayne Centre. David and Mary Turbayne. St Hilda’s School is set to host an Australian ranking tennis tournament tennis development strategy. The centre was fast-tracked through in November following substantial investment in excess of $750,000 in two generous bequests made to the school by Queensland family, facilities and coaching programs by the school and tennis management Mary (nee Dulhunty 1940) and David Turbayne. partner, Pure Tennis Academy. Mary Turbayne’s family has a long history with the school dating back to “Hosting the Tennis Australia junior event is a significant milestone for 1908 when former student and Mary Turbayne’s mother, Sylvia Dulhunty the St Hilda’s Pure Tennis Academy,” said Head of School Peter Crawley. (nee Dixon 1908), attended Goyte-Lea, a girls’ boarding school owned by “The academy was established in 2013 with the aim of attracting many Miss Helena Davenport. Goyte-Lea was re-named St Hilda’s School in 1912. of Queensland’s up and coming, as well as elite players.” Four past students who attended St Hilda’s between 1942 and 1980, The St Hilda’s Pure Tennis Junior Championships will see more than 200 with direct family connections to Sylvia Dulhunty and Mary Turbayne, elite players in the 12 to 16 years age divisions compete on the newly- attended the sports centre opening. -

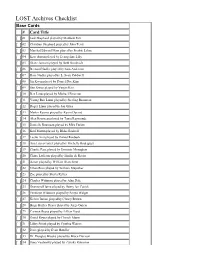

LOST Archives Checklist

LOST Archives Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 Jack Shephard played by Matthew Fox [ ] 02 Christian Shephard played by John Terry [ ] 03 Marshal Edward Mars played by Fredric Lehne [ ] 04 Kate Austin played by Evangeline Lilly [ ] 05 Diane Janssen played by Beth Broderick [ ] 06 Bernard Nadler played by Sam Anderson [ ] 07 Rose Nadler played by L. Scott Caldwell [ ] 08 Jin Kwon played by Daniel Dae Kim [ ] 09 Sun Kwon played by Yunjin Kim [ ] 10 Ben Linus played by Michael Emerson [ ] 11 Young Ben Linus played by Sterling Beaumon [ ] 12 Roger Linus played by Jon Gries [ ] 13 Martin Keamy played by Kevin Durand [ ] 14 Alex Rousseau played by Tania Raymonde [ ] 15 Danielle Rousseau played by Mira Furlan [ ] 16 Karl Martin played by Blake Bashoff [ ] 17 Leslie Arzt played by Daniel Roebuck [ ] 18 Ana Lucia Cortez played by Michelle Rodriguez [ ] 19 Charlie Pace played by Dominic Monaghan [ ] 20 Claire Littleton played by Emilie de Ravin [ ] 21 Aaron played by William Blanchette [ ] 22 Ethan Rom played by William Mapother [ ] 23 Zoe played by Sheila Kelley [ ] 24 Charles Widmore played by Alan Dale [ ] 25 Desmond Hume played by Henry Ian Cusick [ ] 26 Penelope Widmore played by Sonya Walger [ ] 27 Kelvin Inman played by Clancy Brown [ ] 28 Hugo Hurley Reyes played by Jorge Garcia [ ] 29 Carmen Reyes played by Lillian Hurst [ ] 30 David Reyes played by Cheech Marin [ ] 31 Libby Smith played by Cynthia Watros [ ] 32 Dave played by Evan Handler [ ] 33 Dr. Douglas Brooks played by Bruce Davison [ ] 34 Ilana Verdansky played by Zuleika