What Cheap Speech Has Done: (Greater) Equality and Its Discontents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOCAL NEWS IS a PUBLIC GOOD Public Pathways for Supporting Coloradans’ Civic News and Information Needs in the 21St Century

LOCAL NEWS IS A PUBLIC GOOD Public Pathways for Supporting Coloradans’ Civic News and Information Needs in the 21st Century INTRODUCTION A free and independent press was so fundamental to the founding vision of “Congress shall make no law democratic engagement and government accountability in the United States that it is called out in the First Amendment to the Constitution alongside individual respecting an establishment of freedoms of speech, religion, and assembly. Yet today, local newsrooms and religion, or prohibiting the free their ability to fulfill that lofty responsibility have never been more imperiled. At exercise thereof; or abridging the very moment when most Americans feel overwhelmed and polarized by a the freedom of speech, or of the barrage of national news, sensationalism, and social media, Colorado’s local news outlets – which are still overwhelmingly trusted and respected by local residents – press; or the right of the people are losing the battle for the public’s attention, time, and discretionary dollars.1 peaceably to assemble, and to What do Colorado communities lose when independent local newsrooms shutter, petition the Government for a cut staff, merge, or sell to national chains or investors? Why should concerned redress of grievances.” citizens and residents, as well as state and local officials, care about what’s happening in Colorado’s local journalism industry? What new models might First Amendment, U.S. Constitution transform and sustain the most vital functions of a free and independent Fourth Estate: to inform, equip, and engage communities in making democratic decisions? 1 81% of Denver-area adults say the local news media do very well to fairly well at keeping them informed of the important news stories of the day, 74% say local media report the news accurately, and 65% say local media cover stories thoroughly and provide news they use daily. -

Join Us for Wna's Annual Convention

Convention Better Know In the Line 2 Highlights a Newsie of Fire 0 Distinguished speakers, Pamela Henson, new Two murdered Wisconsin- solid programming and publisher at The Post- educated freelancers were a lot of journo fun are in Crescent, shares in riskier situations due to 1 Convention & Trade Show store at the 2015 WNA-AP some good news for a host of modern-day 5 Convention. newspapers. wartime conditions. Feb. 26-27 • Milwaukee Marriott West • #WNAAP15 See Page2. See Page 3. See Page 3. THE News and information for the Wisconsin newspaper industry JANUARY 2015 Bulletin ... among the world’s oldest press associations WNA/AP Convention Join Us for WNA’s Annual Convention Carol O’Leary, WNA President and publisher of The Star News in paper executives like you and me, has Medford, invites members to invest two days in quality programming designed a robust schedule. Each day’s “ The opportunity to share ideas and and networking at the annual WNA/AP Convention and Trade Show. education and networking opportunities experiences with your peers during the sessions are packed with vibrant possibilities to and social times can bring a fresh approach to Dear WNA Members, ready you and your employees for the year ahead. the way we serve our communities.” I’d like to personally invite you to join your newspaper col- leagues at the annual WNA Convention and Trade Show on Feb. Thursday’s program will help you set more. WNA Better Newspaper Contest winners will be displayed 26-27, 2015, at the Milwaukee Marriott West. This year’s event up your organization for success while for viewing in the Trade Show area. -

A Brave New World (PDF)

Dear Reader: In Spring 2005, as part of Cochise College’s 40th anniversary celebration, we published the first installment of Cochise College: A Brave Beginning by retired faculty member Jack Ziegler. Our reason for doing so was to capture for a new generation the founding of Cochise College and to acknowledge the contributions of those who established the College’s foundation of teaching and learning. A second, major watershed event in the life of the College was the establishment of the Sierra Vista Campus. Dr. Ziegler has once again conducted interviews and researched archived news paper accounts to create a history of the Sierra Vista Campus. As with the first edition of A Brave Beginning, what follows is intended to be informative and entertaining, capturing not only the recorded events but also the memories of those who were part of expanding Cochise College. Dr. Karen Nicodemus As the community of Sierra Vista celebrates its 50th anniversary, the College takes great pleas ure in sharing the establishment of the Cochise College Sierra Vista Campus. Most importantly, as we celebrate the success of our 2006 graduates, we affirm our commitment to providing accessible and affordable higher education throughout Cochise County. For those currently at the College, we look forward to building on the work of those who pio neered the Douglas and Sierra Vista campuses through the College’s emerging districtwide master facilities plan. We remain committed to being your “community” college – a place where teaching and learning is the highest priority and where we are creating opportunities and changing lives. Karen A. -

Understaffed, Overutilized

SPORTS BUSINESS Valley hoops coaches All I Saw, set to exit reflect on experience Wasilla on April 30 after at McDonald’s 39 years in business. All-American games. Page 10 Page 9 FrontierMat-Su Valley sm a n VOLUME 70, NUMBER 85 WEDNESDAY, APRIL 4, 2018 • WWW.FRONTIERSMAN.COM 75 CENTS Understaffed, overutilized UAA study shows Troopers are stretched too thin in the Valley Story on page 7 MORE THAN BANDAIDS: VALLEY GROWN: BLUFF: INDEX Obituaries . 8 Business . 15 Wasilla Middle School Nurse Former Colony Does the RCA Opinion . .14 awarded for her ‘Brain Train’ standout leads college have any teeth? Calendar . 2 team in home runs. Classifieds . 16 Sports . 10 program. Comics . 5 Page 3 Page 11 Page 12 Just for fun . 5 Weather . 2 Turn in your unused or expired Got Drugs? medication for safe disposal For more information Matanuska-Susitna Borough Saturday, April 28, 2018 10am–2pm (907) 861-8557 [email protected] XNLV377690 Palmer Fred Meyer Wasilla Fred Meyer Talkeetna Sunshine Community Health Center WEDNESDAY, APRIL 4, 2018 Serving the Mat-Su Valley since 1947 Frontiersman MAT-SU VALLEY 6-DAY FORECAST © Frontiersman 2018 WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY The Frontiersman is a division HIGH: 35 HIGH: 41 HIGH: 42 HIGH: 45 HIGH: 46 HIGH: 44 of Wick Communications Co. LOW: 26 LOW: 20 LOW: 21 LOW: 22 LOW: 30 LOW: 31 Visit us on the Web at www.frontiersman.com On tap PM Snow Showers Partly Cloudy Partly Cloudy Sunny Sunny Partly Cloudy PHYSICAL ADDRESS 5751 E. Mayflower Ct. Wasilla, AK 99654 MAILING ADDRESS UPCOMING APRIL 5751 E. -

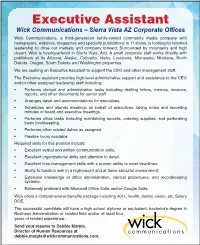

Executive Assistant

Executive Assistant Wick Communications – Sierra Vista AZ Corporate Offices Wick Communications, a third-generation family-owned community media company with newspapers, websites, magazines and specialty publications in 11 states, is looking for talented leadership to drive our markets and company forward. Surrounded by mountains and high desert, Wick is headquartered in Sierra Vista, Ariz. A small corporate staff works directly with publishers at its Arizona, Alaska, Colorado, Idaho, Louisiana, Minnesota, Montana, North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota and Washington properties. We are seeking an Executive Assistant to support the CEO and other management staff. The Executive assistant provides high-level administrative support and assistance to the CEO and/or other assigned leadership staff including: • Performs clerical and administrative tasks including drafting letters, memos, invoices, reports, and other documents for senior staff. • Arranges travel and accommodations for executives. • Schedules and attends meetings on behalf of executives, taking notes and recording minutes of board and executive meetings. • Performs office tasks including maintaining records, ordering supplies, and performing basic bookkeeping. • Performs other related duties as assigned. • Flexible hours available. Required skills for this position include: • Excellent verbal and written communication skills. • Excellent organizational skills and attention to detail. • Excellent time management skills with a proven ability to meet deadlines. • Ability to function well in a high-paced and at times stressful environment. • Extensive knowledge of office administration, clerical procedures, and recordkeeping systems. • Extremely proficient with Microsoft Office Suite and/or Google Suite. Wick offers a comprehensive benefits package including 401k, health, dental, vision, etc. Salary DOE. The successful candidate will have a high school diploma or equivalent, bachelor’s degree in Business Administration or related field and/or at least four years of related experience. -

Press Pass January 2017

PAGE 1 PRESSPASS January 27, 2017 Best Lifestyle Photo Division 3 2016 Better Newspaper Contest By Matt Baldwin, Whitefish Pilot Titled: Skaters Judge’s Comments: This image is clean and graphic. The wide shot from farther away gives a good sense of place. January 27, 2017 PAGE 2 MNACalendar February 1 Begin accepting nominations for the 2017 Montana Newspaper Hall of Fame and Master Editor/Publisher Awards 14 2017 Better Newspaper Contest is closed to entries at 10:00 pm 17 Deadline to submit articles for the February Press Pass March 10 Job and Internship Fair - U of M School of Journalism. For more info, email journalism.umt.edu 12 Sunshine Week 17 Sunshine Week Event sponsored by the MNA, MT FOI Hotline and MBA - Montana Capitol, Helena 17 Deadline to submit articles for the March Press Pass 30 High School Journalism Day - U of M School of Journalism 31 Deadline to submit nominations for the 2017 Montana Newspaper Hall of Fame and Master Editor/Publisher Awards April 15 Montana Corporation Annual Report filing deadline with the Montana Secretary of State 20 Dean Stone Lecture - U of M UC Ballroom at 7:00 pm 21 MNA and MNAS Board of the Directors’ meeting - Don Anderson Hall U of M School of Journalism 21 Dean Stone Banquet - Holiday Inn, Missoula 21 Deadline to submit articles for the April Press Pass May 19 Deadline to submit articles for the May Press Pass 29 MNA office will be closed for the Memorial Day holiday June 8 MNA and MNAS Board of Directors’ Meeting - Pine Meadow Golf Course, Lewistown 8, 9 MNA office will be closed for -

Robert Wick Living Bronze Sculpture

Praying Plantis, 2011, bronze, yucca, agave, mescal and cholla, 7’6” tall on base. Praying Plantis unites plants and sculpture in a state of prayer and meditation. “Until you can grow a tree from your own heart you’ll never understand the oneness of all things,” says Bob Wick, creator of bronze The evolution of the earth is the pulsating heart of mankind. sculptures that carry living plants Both earth and humankind grow new forms, new life, new and trees. Wick explains the par- states of being. Both are always in change. We and the earth allels of earth and humanity: are shaped by the energy and forces put upon and within. “We humans are structured We are only a recent manifestation of the earth’s evolutionary like the earth we come from. The force ... and the part we play is the conscious earth.” earth has strata of rocks and dirt. Wick concludes: “I am hopeful that my work will allow others Our strata are genetics and per- to see a synthesis of earth, life and man, so that each of us can sonal environment. grow a tree from our own heart. Maybe then will we make the The earth has earthquakes. right decisions for a better earth and life.” We have love, birth and death. The earth has volcanos. We have pain, violence and creation. It all comes from beneath. robertwick.com Arroyo Rising (above) 2013, bronze, yucca, prickly pear, mesquite, ocotillo and cholla, 15’ tall. Arroyo Rising defines a section of earth that rises out of the landscape carrying the plant life of a desert wash with it. -

Industry Letter Is Here

2020/2021 NNA OFFICERS April 13, 2021 Chair The Honorable Xavier Becerra Brett Wesner Wesner Publications Secretary of Health and Human Services Cordell, OK Hubert H Humphrey Building 200 Independence Ave SW Vice Chair John Galer Washington DC 20201 The Hillsboro Journal-New Hillsboro, IL Dear Secretary Becerra: Treasurer Jeff Mayo We write as publishers, editors and journalists at the nation’s community newspapers to urge your Cookson Hills Publishing attention to our important role in addressing small, rural, ethnic and minority communities in the new “We Sallisaw, OK Can Do This Campaign.” BOARD OF DIRECTORS Our newspapers are reaching the audiences you are looking for. We publish weekly and daily in print and Martha Diaz-Aszkenazy hourly on digital platforms to people seeking local news. Our readers are old, young, Republicans, San Fernando Valley Sun San Fernando, CA Democrats and Independents, who are highly motivated to vote, engage in civic leadership and develop their small communities. These are the audiences who can help to get shots into arms. Beth Bennett Wisconsin Newspaper Association Madison, WI To date, despite guidance from Congress in the Department’s 2021 appropriations legislation to make better use of local media, our newspapers have not been contacted for the $10 billion advertising J. Louis Mullen Blackbird LLC campaign. Newport, WA The HHS advertising should appear in April and May on our print pages, on our website and on our William Jacobs Jacobs Properties Facebook posts. Your message in our publications will be highly-focussed in a medium that is best Brookhaven, MS designed to handle powerful, complex and urgent messages. -

Industry News Next Week's Digital Ad Webinar: Executing Digital 1St-Time Client Meetings

August 13, 2021 To submit an item for the next newsletter, email [email protected] Industry news Painted (and sponsored) newspaper boxes recently unveiled in Newnan, Ga. Local artists have painted beautiful designs on a selection of The Newnan (Georgia) Times-Herald boxes that are displayed around Newnan. The boxes are fully operable and will contain free copies of the paper, provided through sponsorships that also will benefit the Children Connect Museum, in partnership with the Newnan- Coweta Art Association. READ MORE 5 strategies to uncover bias in data A poll, survey or other dataset may look like an example of objective truth. But human choices shape the creation of a data product — and its interpretation. So how can journalists fairly report on this data? READ MORE Next Week's Digital Ad Webinar: Executing Digital 1st-Time Client Meetings FREE for members of America's Newspapers Wednesday, August 18 3 p.m. EDT / 2 p.m. CDT / 1 p.m. MDT / Noon PDT Part 3 in our Digital Ad Sales series is about engaging with the prospect. Trey Morris, vice president/senior consultant with The Center for Sales Strategy, will share techniques that will help you lead the conversation. Gain insights to help you make the connection and discover the desired business results that your prospect wants to achieve. You will learn the questions to ask during your appointment and the next steps to keep the sales process moving forward. This will give you the skills you need to prepare for and provide a successful first-time REGISTER meeting. Take your entire team through our five-part digital sales training program and pump up your digital sales! FREE for members; $150 for nonmembers This webinar series is designed for newspaper sales If you took part in the first sessions in executives and managers. -

Total Audience 191 2018

471,000 Total Audience 191 2018 in Southern Arizona San Carlos Graham County Greenlee 70 County Bylas Clifton Fort Thomas Morenci Eden 78 MEDIA Pima A rizona Regi ona l M e d i a Central Sa ord 191 73 A D i vis i o n o f W i ck C o m m u n ica tion s Thatcher Solomon 191 70 Duncan KIT ARIZONA REGIONAL MEDIA (ARM) 191 Pima County I-10 Bowie Wilcox San Simon Tucson I-10 186 Cochise I-10 Dragoon 191 Cochise Sahuarita Vail Pomerene Benson I-10 County I-19 80 St. Da Pearce Green Valley 83 181 90 El Frida 82 Tombstone Amado Elgin 80 Tubac 83 191 Huachuca City 80 Arivaca Tumacacori Sonoita Ft. Huachuca McNeal Santa Cruz 82 Patagonia 90 County Sierra Vista Rio Rico Bisbee Hereford 80 92 Pirtleville Nogales Naco Douglas ARIZONA NEWSPAPER GROUP (ARM) Wick Communications CINDY HEFLEY INESE KALNINS ALESSIA ALAIMO RENEE HAUSER A rizona Regi ona l M e d i a A D i vis i o n o f W i ck C o m m u n ica tion s DIRECTOR OF ADVERTISING REGIONAL ARIZONA EXECUTIVE DIGITAL MEDIA MANAGER (520)515.5981 (520)743.2976 (520)310.9901 (520)295.4240 (520)844.8969 fax cindy.hefl [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] www.wickcommunications.com YOUR LOCAL NEWS. YOUR COMMUNITY. YOUR VOICE. www.willcoxrangenews.com www.eacourier.com/copper_era www.douglasdispatch.com www.eacourier.com ARIZONA RANGE NEWS THE COPPER ERA DOUGLAS DISPATCH EASTERN ARIZONA COURIER PUBLISHED WEDNESDAYS PUBLISHED WEDNESDAYS PUBLISHED WEDNESDAYS PUBLISHED WED & SAT AUDIENCE AUDIENCE AUDIENCE AUDIENCE Nogales -

Now Hiring 1

Williston Herald 14 W. 4th St. CLASSIFIED Williston ND 58801 A7 701-572-2165 Wednesday, MARKETPLACE April 28, 2021 CALL Legal Legal Sarah Wilson-Boda (701) 572-2165 Public Notice Public Notice IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF IN THE STATE OF NORTH DAKOTA, WILLIAMS COUNTY, COUNTY OF WILLIAMS STATE OF NORTH DAKOTA Toll-free IN THE DISTRICT COURT, NORTHWEST JUDICIAL DISTRICT In the Matter of the Estate of (800) 950-2165 LOLA MAE HUWE, deceased Guild Mortgage Company LLC f/k/a Guild Mortgage Company, Probate No. 53-2021-PR-00089 Plaintiff, E-MAIL v. NOTICE OF HEARING PETITION FOR Daniel J. Berthe; any person in possessi APPLICATION FOR FORMAL [email protected] on, and all persons unknown, claiming PROBATE OF WILL AND any estate or interest in, or lien or encum- APPOINTMENT OF PERSONAL brance upon, the real estate described in REPRESENTATIVE [email protected] the complaint, Defendants. NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that Julie Gay Huwe has filed herein an Application FAX NOTICE OF REAL ESTATE SALE for Formal Probate of Will and Appoint- CIVIL NUMBER: 53-2020-CV-01519 ment of Personal Representative. (701) 572-9563 Hearing has been set upon said petition NOW HIRING 1. Judgment in the amount of on the 18th day of May, 2021, at 4:30 o'- $200,405.15, having been entered in fa- clock P.M., Central Time at the Court- vor of Plaintiff and against Defendants, room of the above named Court in the which Judgment was filed with the Clerk City of Williston, County of Williams, State of Courts of Williams County, North Dako- of North Dakota. -

The Latest News Sales Compensation Study "We Cannot Protect Our

June 16, 2020 The Latest News Sales Compensation Study Participate free by July 17 Newspaper Sales Compensation Study to give publishers and advertising directors the tools needed to better compete for sales talent A Newspaper Sales Compensation Study sponsored by America's Newspapers, Editor & Publisher and Media Staffing Network will help owners and operators better gauge how to compensate both entry-level and experienced sellers. READ MORE and PARTICIPATE FREE "We cannot protect our democracy, if we do not protect our press." Senator Markey, colleagues introduce press freedom resolution Senator Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.) has announced introduction of a Senate resolution condemning attacks against members of the media and reaffirming the centrality of a free and independent press and peaceful assembly to the health of democracy in the United States. America's Newspapers applauds this resolution, which comes in the wake of the arrest on May 29 of CNN reporters covering protests in Minnesota. READ MORE We're in E&P Magazine! Read the America's Newspapers section in this month's Editor & Publisher magazine Be sure to flip to pages 43-46 in this month's printed edition of Editor & Publisher magazine to read the new America's Newspapers section. This issue features a look at: Our legislative priorities. A column from CEO Dean Ridings. Our latest marketing campaign produced for members. Our leadership. Three areas newspapers should be addressing, that might have been overlooked during the pandemic. VIEW OUR PAGES in E&P READ MORE from E&P Add Your Paper to List of Participating Members Thank you for supporting America's Newspapers through Donated Ad Program Special thanks to the growing list of America's Newspapers members who are participating in our Donated Ad Program.