Outsourcing Law in Post-Soviet Russia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information on IRC – R.O.S.T., the Registrar of the Company and the Acting Ballot Committee of MMC Norilsk Nickel

Information on IRC – R.O.S.T., the registrar of the Company and the acting Ballot Committee of MMC Norilsk Nickel IRC – R.O.S.T. (former R.O.S.T. Registrar merged with Independent Registrar Company in February 2019) was established in 1996. In 2003–2015, Independent Registrar Company was a member of Computershare Group, a global leader in registrar and transfer agency services. In July 2015, IRC changed its ownership to pass into the control of a group of independent Russian investors. In December 2016, R.O.S.T. Registrar and Independent Registrar Company, both owned by the same group of independent investors, formed IRC – R.O.S.T. Group of Companies. In 2018, Saint Petersburg Central Registrar joined the Group. In February 2019, Independent Registrar Company merged with IRC – R.O.S.T. Ultimate beneficiaries of IRC – R.O.S.T. Group are individuals with a strong background in business management and stock markets. No beneficiary holds a blocking stake in the Group. In accordance with indefinite License No. 045-13976-000001, IRC – R.O.S.T. keeps records of holders of registered securities. Services offered by IRC – R.O.S.T. to its clients include: › Records of shareholders, interestholders, bondholders, holders of mortgage participation certificates, lenders, and joint property owners › Meetings of shareholders, joint owners, lenders, company members, etc. › Electronic voting › Postal and electronic mailing › Corporate consulting › Buyback of securities, including payments for securities repurchased › Proxy solicitation › Call centre services › Depositary and brokerage, including escrow agent services IRC – R.O.S.T. Group invests a lot in development of proprietary high-tech solutions, e.g. -

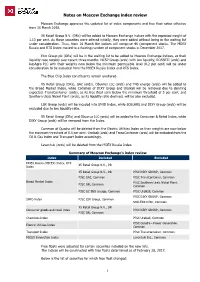

Notes on Moscow Exchange Index Review

Notes on Moscow Exchange index review Moscow Exchange approves the updated list of index components and free float ratios effective from 16 March 2018. X5 Retail Group N.V. (DRs) will be added to Moscow Exchange indices with the expected weight of 1.13 per cent. As these securities were offered initially, they were added without being in the waiting list under consideration. Thus, from 16 March the indices will comprise 46 (component stocks. The MOEX Russia and RTS Index moved to a floating number of component stocks in December 2017. En+ Group plc (DRs) will be in the waiting list to be added to Moscow Exchange indices, as their liquidity rose notably over recent three months. NCSP Group (ords) with low liquidity, ROSSETI (ords) and RosAgro PLC with their weights now below the minimum permissible level (0.2 per cent) will be under consideration to be excluded from the MOEX Russia Index and RTS Index. The Blue Chip Index constituents remain unaltered. X5 Retail Group (DRs), GAZ (ords), Obuvrus LLC (ords) and TNS energo (ords) will be added to the Broad Market Index, while Common of DIXY Group and Uralkali will be removed due to delisting expected. TransContainer (ords), as its free float sank below the minimum threshold of 5 per cent, and Southern Urals Nickel Plant (ords), as its liquidity ratio declined, will be also excluded. LSR Group (ords) will be incuded into SMID Index, while SOLLERS and DIXY Group (ords) will be excluded due to low liquidity ratio. X5 Retail Group (DRs) and Obuvrus LLC (ords) will be added to the Consumer & Retail Index, while DIXY Group (ords) will be removed from the Index. -

Overlap Issues Consent Order

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE CHANCERY DIVISION The Honourable Mrs Justice Gloster DBE 12 October 2012 BETWEEN:- HCO8C03549 BORIS BEREZOVSICY Claimant - and - INNA GUDAVADZE & OTHERS Defendants HCO9C00494 BORIS BEREZOVSKY Claimant - and - VASILY ANISIMOV & OTHERS Defendants HCO9C00711 BORIS BEREZOVSICY Claimant - and - SALFORD CAPITAL PARTNERS INC & OTHERS Defendants 1),D 1147 (f) MEEK ORDER UPON the Order of Mr Justice Mann and Mrs Justice Gloster DBE dated 16 August 2010, ordering the trial of the issues set out in paragraph 1 of that Order (the Overlap Issues) as preliminary issues in proceedings number HC08C03549 (the Main Action), HC09C00494 (the Metalloinvest Action) and HCO9C00711 (the Salford Action); AND UPON the trial of the Overlap Issues (as amended by subsequent Orders) together with the trial of the Claimant's claims in Commercial Court proceedings number 2007 Folio 942 (the Joint Trial); AND UPON the Court having heard oral evidence and having read the written evidence filed; AND UPON hearing Leading Counsel for the Claimant, Counsel for the Second to Fifth Defendants in the Main Action (the Family Defendants), Leading Counsel for the Third to Fifth and Tenth Defendants in the Metalloinvest Action (the Anisimov Defendants), and Counsel for the Fourth to Ninth and Eleventh Defendants in the Salford Action (the Salford Defendants); AND UPON the Court having given judgment on the Overlap Issues on 31 August 2012; AND UPON the parties having agreed the orders as to costs set out in paragraphs 2 to 5 of this Order below; IT IS ORDERED THAT:- Determination of the Overlap Issues 1. The Overlap Issues are determined as follows:- (1) The Claimant did not acquire any interest in any Russian aluminium industry assets prior to the alleged meeting at the Dorchester Hotel in March 2000 (other than as a result of the alleged overarching joint venture agreement alleged by the Claimant in the Main Action, in relation to which no findings are made). -

November 1-30, 2020

UZBEKISATN– NOVEMBER 1-30, 2020 UZBEKISATN– NOVEMBER 1-30, 2020 ....................................................................................................................................... 1 TOP NEWS OF THE PERIOD ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Government intends to increase excise tax rates on petrol and diesel 2 Leading trade partners of Uzbekistan 2 POLITICS AND LAW ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Namangan plans to build an international business center: Alisher Usmanov to contribute to the implementation of the project 3 Uzbekistan rises in the Legatum Prosperity Index 3 Worldwide Cost of Living 2020 report: Tashkent among cheapest cities to live in 4 International Organization of Migration to open its office in Uzbekistan 4 Central Asia, EU reaffirm their commitment to build strong relations 5 Facilitating Uzbekistan's Accession to the WTO 7 Economy AND FINANCE ...................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Uzbekistan takes first place in the world in terms of gold sold in the third quarter 8 The National Venture Fund UzVC is being created 8 Diesel fuel production of Euro-4 and Euro-5 standards starts in Ferghana region 9 Food -

Preventing Deglobalization: an Economic and Security Argument for Free Trade and Investment in ICT Sponsors

Preventing Deglobalization: An Economic and Security Argument for Free Trade and Investment in ICT Sponsors U.S. CHAMBER OF COMMERCE FOUNDATION U.S. CHAMBER OF COMMERCE CENTER FOR ADVANCED TECHNOLOGY & INNOVATION Contributing Authors The U.S. Chamber of Commerce is the world’s largest business federation representing the interests of more than 3 million businesses of all sizes, sectors, and regions, as well as state and local chambers and industry associations. Copyright © 2016 by the United States Chamber of Commerce. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form—print, electronic, or otherwise—without the express written permission of the publisher. Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 6 Part I: Risks of Balkanizing the ICT Industry Through Law and Regulation ........................................................................................ 11 A. Introduction ................................................................................................. 11 B. China ........................................................................................................... 14 1. Chinese Industrial Policy and the ICT Sector .................................. 14 a) “Informatizing” China’s Economy and Society: Early Efforts ...... 15 b) Bolstering Domestic ICT Capabilities in the 12th Five-Year Period and Beyond ................................................. 16 (1) 12th Five-Year -

Telenor Mobile Communications AS V. Storm LLC

07-4974-cv(L); 08-6184-cv(CON); 08-6188-cv(CON) Telenor Mobile Communications AS v. Storm LLC Lynch, J. S.D.N.Y. 07-cv-6929 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT SUMMARY ORDER RULINGS BY SUMMARY ORDER DO NOT HAVE PRECEDENTIAL EFFECT. CITATION TO SUMMARY ORDERS FILED AFTER JANUARY 1, 2007, IS PERMITTED AND IS GOVERNED BY THIS COURT’S LOCAL RULE 32.1 AND FEDERAL RULE OF APPELLATE PROCEDURE 32.1. IN A BRIEF OR OTHER PAPER IN WHICH A LITIGANT CITES A SUMMARY ORDER, IN EACH PARAGRAPH IN WHICH A CITATION APPEARS, AT LEAST ONE CITATION MUST EITHER BE TO THE FEDERAL APPENDIX OR BE ACCOMPANIED BY THE NOTATION: (SUMMARY ORDER). A PARTY CITING A SUMMARY ORDER MUST SERVE A COPY OF THAT SUMMARY ORDER TOGETHER WITH THE PAPER IN WHICH THE SUMMARY ORDER IS CITED ON ANY PARTY NOT REPRESENTED BY COUNSEL UNLESS THE SUMMARY ORDER IS AVAILABLE IN AN ELECTRONIC DATABASE WHICH IS PUBLICLY ACCESSIBLE WITHOUT PAYMENT OF FEE (SUCH AS THE DATABASE AVAILABLE AT HTTP://WWW.CA2.USCOURTS.GOV/). IF NO COPY IS SERVED BY REASON OF THE AVAILABILITY OF THE ORDER ON SUCH A DATABASE, THE CITATION MUST INCLUDE REFERENCE TO THAT DATABASE AND THE DOCKET NUMBER OF THE CASE IN WHICH THE ORDER WAS ENTERED. 1 At a stated term of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, held at the 2 Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse, 500 Pearl Street, in the City of New York, on 3 the 8th day of October, two thousand nine, 4 5 PRESENT: 6 ROBERT D. -

Treisman Silovarchs 9 10 06

Putin’s Silovarchs Daniel Treisman October 2006, Forthcoming in Orbis, Winter 2007 In the late 1990s, many Russians believed their government had been captured by a small group of business magnates known as “the oligarchs”. The most flamboyant, Boris Berezovsky, claimed in 1996 that seven bankers controlled fifty percent of the Russian economy. Having acquired massive oil and metals enterprises in rigged privatizations, these tycoons exploited Yeltsin’s ill-health to meddle in politics and lobby their interests. Two served briefly in government. Another, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, summed up the conventional wisdom of the time in a 1997 interview: “Politics is the most lucrative field of business in Russia. And it will be that way forever.”1 A decade later, most of the original oligarchs have been tripping over each other in their haste to leave the political stage, jettisoning properties as they go. From exile in London, Berezovsky announced in February he was liquidating his last Russian assets. A 1 Quoted in Andrei Piontkovsky, “Modern-Day Rasputin,” The Moscow Times, 12 November, 1997. fellow media magnate, Vladimir Gusinsky, long ago surrendered his television station to the state-controlled gas company Gazprom and now divides his time between Israel and the US. Khodorkovsky is in a Siberian jail, serving an eight-year sentence for fraud and tax evasion. Roman Abramovich, Berezovsky’s former partner, spends much of his time in London, where he bought the Chelsea soccer club in 2003. Rather than exile him to Siberia, the Kremlin merely insists he serve as governor of the depressed Arctic outpost of Chukotka—a sign Russia’s leaders have a sense of humor, albeit of a dark kind. -

RUSSIA INTELLIGENCE Politics & Government

N°66 - November 22 2007 Published every two weeks / International Edition CONTENTS KREMLIN P. 1-4 Politics & Government c KREMLIN The highly-orchestrated launching into orbit cThe highly-orchestrated launching into orbit of of the «national leader» the «national leader» Only a few days away from the legislative elections, the political climate in Russia grew particu- STORCHAK AFFAIR larly heavy with the announcement of the arrest of the assistant to the Finance minister Alexey Ku- c Kudrin in the line of fire of drin (read page 2). Sergey Storchak is accused of attempting to divert several dozen million dol- the Patrushev-Sechin clan lars in connection with the settlement of the Algerian debt to Russia. The clan wars in the close DUMA guard of Vladimir Putin which confront the Igor Sechin/Nikolay Patrushev duo against a compet- cUnited Russia, electoral ing «Petersburg» group based around Viktor Cherkesov, overflows the limits of the «power struc- home for Russia’s big ture» where it was contained up until now to affect the entire Russian political power complex. business WAR OF THE SERVICES The electoral campaign itself is unfolding without too much tension, involving men, parties, fac- cThe KGB old guard appeals for calm tions that support President Putin. They are no longer legislative elections but a sort of plebicite campaign, to which the Russian president lends himself without excessive good humour. The objec- PROFILE cValentina Matvienko, the tive is not even to know if the presidential party United Russia will be victorious, but if the final score “czarina” of Saint Petersburg passes the 60% threshhold. -

Russian Games Market Report.Pdf

Foreword Following Newzoo’s free 42-page report on China and its games market, this report focuses on Russia. This report aims to provide understanding of the Russian market by putting it in a broader perspective. Russia is a dynamic and rapidly growing games We hope this helps to familiarize our clients and friends market, currently number 12 in the world in terms of around the globe with the intricacies of the Russian revenues generated. It is quickly becoming one of market. the most important players in the industry and its complexity warrants further attention and This report begins with some basic information on examination. The Russian market differs from its demographics, politics and cultural context, as well as European counterparts in many ways and this can be brief descriptions of the media, entertainment, telecoms traced to cultural and economic traditions, which in and internet sectors. It also contains short profiles of the some cases are comparable to their Asian key local players in these sectors, including the leading neighbours. local app stores, Search Engines and Social Networks. Russia has been a part of the Newzoo portfolio since In the second part of the report we move onto describe 2011, allowing us to witness first-hand the the games market in more detail, incorporating data unprecedented growth and potential within this from our own primary consumer research findings as market. We have accumulated a vast array of insights well as data from third party sources. on both the Russian consumers and the companies that are feeding this growth, allowing us to assist our clients with access to, and interpretation of, data on We also provide brief profiles of the top games in Russia, the Russia games market. -

Selecting Import Products and Suppliers 409

Chapter 17 SelectingSelecting Import Import Products andProducts Suppliers and Suppliers TYPES OF PRODUCTS FOR IMPORTATION One of the most important import decisions is the selection of the proper product that serves the market need. In the absence of the latter, one is left with a warehouse full of merchandise with no one interested in buying it. Nevertheless, importing can become a successful and profitable venture so long as sufficient effort and time is invested in selecting the right product for the target market. How does one find the right product to import? The following are differ- ent types of products to consider. Unique Products Products that are unique and different can be appealing to customers be- cause they are a welcome change from the standardized and identical prod- ucts sold in the domestic market. The fact that a product is imported and different is in itself sufficient for many people to purchase the item. However, some studies indicate product uniqueness in terms of cultural appeal to be a relatively less important variable in the purchasing decision of import man- agers (Ghymn, 1983). Less Expensive Products It is quite common to find imports that perform identically to the competi- tor’s product but can be sold at a much lower price. As customers quickly switch allegiance to buy the imported item, it is quite possible to capture a substantial share of the domestic market. Export-Import Theory, Practices, and Procedures, Second Edition 407 408 EXPORT-IMPORT THEORY, PRACTICES, AND PROCEDURES For firms selling in mature markets where there is little or no product dif- ferentiation, cost reduction provides a competitive advantage (Shippen, 1999). -

William R. Spiegelberger the Foreign Policy Research Institute Thanks the Carnegie Corporation for Its Support of the Russia Political Economy Project

Russia Political Economy Project William R. Spiegelberger The Foreign Policy Research Institute thanks the Carnegie Corporation for its support of the Russia Political Economy Project. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Author: William R. Spiegelberger Eurasia Program Leadership Director: Chris Miller Deputy Director: Maia Otarashvili Edited by: Thomas J. Shattuck Designed by: Natalia Kopytnik © 2019 by the Foreign Policy Research Institute April 2019 COVER: Designed by Natalia Kopytnik. Photography: Oleg Deripaska (World Economic Forum); St. Basil’s Cathedral (Adob Stock); Ruble (Adobe Stock); Vladimir Putin (kremlin.ru); Rusal logo (rusal.ru); United States Capitol (Adobe Stock; Viktor Vekselberg (Aleshru/Wikimedia Commons); Alumnium rolls (Adobe Stock); Trade War (Adobe Stock). Our Mission The Foreign Policy Research Institute is dedicated to bringing the insights of scholarship to bear on the foreign policy and national security challenges facing the United States. It seeks to educate the public, teach teachers, train students, and offer ideas to advance U.S. national interests based on a nonpartisan, geopolitical perspective that illuminates contemporary international affairs through the lens of history, geography, and culture. Offering Ideas In an increasingly polarized world, we pride ourselves on our tradition of nonpartisan scholarship. We count among our ranks over 100 affiliated scholars located throughout the nation and the world who appear regularly in national and international media, testify on Capitol Hill, and are consulted by U.S. -

Deal Drivers Russia

February 2010 Deal Drivers Russia A survey and review of Russian corporate finance activity Contents Introduction 1 01 M&A Review 2 Overall deal trends 3 Domestic M&A trends 6 Cross-border M&A trends 8 Private equity 11 Acquisition finance 13 Valuations 14 02 Industries 15 Automotive 16 Energy 18 Financial Services 20 Consumer & Retail 22 Industrial Markets 24 Life Sciences 26 Mining 28 Technology, Media & Telecommunications 30 03 Survey Analysis 32 Introduction Prediction may be fast going out of fashion. At the end of 2008, CMS commissioned mergermarket to interview 100 Russian M&A and corporate decision makers to find out what they thought about the situation at the time and what their views on the future were. Falling commodity prices were viewed as the biggest threat, the Financial Services sector was expected to deliver the greatest growth for M&A activity and the bulk of inward investment was expected from Asia. The research revealed that two thirds of the respondents expected the overall level of M&A activity to increase over the course of 2009, with only one third predicting a fall. That third of respondents was right and, in general, the majority got it wrong or very wrong. The survey did get some things right – the predominance of Who knows? What’s the point? We consider the point to be the domestic players, the increase of non-money deals, the in the detail. Our survey looks at the market in 2009 sector number of transactions against a restructuring background, by sector – what was ‘in’ and what was ‘out’.