Journal of Bilingual Education Research & Instruction 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modeling Language Variation and Universals: a Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing

Modeling Language Variation and Universals: A Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing Edoardo Ponti, Helen O ’Horan, Yevgeni Berzak, Ivan Vulic, Roi Reichart, Thierry Poibeau, Ekaterina Shutova, Anna Korhonen To cite this version: Edoardo Ponti, Helen O ’Horan, Yevgeni Berzak, Ivan Vulic, Roi Reichart, et al.. Modeling Language Variation and Universals: A Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing. 2018. hal-01856176 HAL Id: hal-01856176 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01856176 Preprint submitted on 9 Aug 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Modeling Language Variation and Universals: A Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing Edoardo Maria Ponti∗ Helen O’Horan∗∗ LTL, University of Cambridge LTL, University of Cambridge Yevgeni Berzaky Ivan Vuli´cz Department of Brain and Cognitive LTL, University of Cambridge Sciences, MIT Roi Reichart§ Thierry Poibeau# Faculty of Industrial Engineering and LATTICE Lab, CNRS and ENS/PSL and Management, Technion - IIT Univ. Sorbonne nouvelle/USPC Ekaterina Shutova** Anna Korhonenyy ILLC, University of Amsterdam LTL, University of Cambridge Understanding cross-lingual variation is essential for the development of effective multilingual natural language processing (NLP) applications. -

Essentials of Language Typology

Lívia Körtvélyessy Essentials of Language Typology KOŠICE 2017 © Lívia Körtvélyessy, Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky, Filozofická fakulta UPJŠ v Košiciach Recenzenti: Doc. PhDr. Edita Kominarecová, PhD. Doc. Slávka Tomaščíková, PhD. Elektronický vysokoškolský učebný text pre Filozofickú fakultu UPJŠ v Košiciach. Všetky práva vyhradené. Toto dielo ani jeho žiadnu časť nemožno reprodukovať,ukladať do informačných systémov alebo inak rozširovať bez súhlasu majiteľov práv. Za odbornú a jazykovú stánku tejto publikácie zodpovedá autor. Rukopis prešiel redakčnou a jazykovou úpravou. Jazyková úprava: Steve Pepper Vydavateľ: Univerzita Pavla Jozefa Šafárika v Košiciach Umiestnenie: http://unibook.upjs.sk Dostupné od: február 2017 ISBN: 978-80-8152-480-6 Table of Contents Table of Contents i List of Figures iv List of Tables v List of Abbreviations vi Preface vii CHAPTER 1 What is language typology? 1 Tasks 10 Summary 13 CHAPTER 2 The forerunners of language typology 14 Rasmus Rask (1787 - 1832) 14 Franz Bopp (1791 – 1867) 15 Jacob Grimm (1785 - 1863) 15 A.W. Schlegel (1767 - 1845) and F. W. Schlegel (1772 - 1829) 17 Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767 – 1835) 17 August Schleicher 18 Neogrammarians (Junggrammatiker) 19 The name for a new linguistic field 20 Tasks 21 Summary 22 CHAPTER 3 Genealogical classification of languages 23 Tasks 28 Summary 32 CHAPTER 4 Phonological typology 33 Consonants and vowels 34 Syllables 36 Prosodic features 36 Tasks 38 Summary 40 CHAPTER 5 Morphological typology 41 Morphological classification of languages (holistic -

Languages of New York State Is Designed As a Resource for All Education Professionals, but with Particular Consideration to Those Who Work with Bilingual1 Students

TTHE LLANGUAGES OF NNEW YYORK SSTATE:: A CUNY-NYSIEB GUIDE FOR EDUCATORS LUISANGELYN MOLINA, GRADE 9 ALEXANDER FFUNK This guide was developed by CUNY-NYSIEB, a collaborative project of the Research Institute for the Study of Language in Urban Society (RISLUS) and the Ph.D. Program in Urban Education at the Graduate Center, The City University of New York, and funded by the New York State Education Department. The guide was written under the direction of CUNY-NYSIEB's Project Director, Nelson Flores, and the Principal Investigators of the project: Ricardo Otheguy, Ofelia García and Kate Menken. For more information about CUNY-NYSIEB, visit www.cuny-nysieb.org. Published in 2012 by CUNY-NYSIEB, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, NY, NY 10016. [email protected]. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Alexander Funk has a Bachelor of Arts in music and English from Yale University, and is a doctoral student in linguistics at the CUNY Graduate Center, where his theoretical research focuses on the semantics and syntax of a phenomenon known as ‘non-intersective modification.’ He has taught for several years in the Department of English at Hunter College and the Department of Linguistics and Communications Disorders at Queens College, and has served on the research staff for the Long-Term English Language Learner Project headed by Kate Menken, as well as on the development team for CUNY’s nascent Institute for Language Education in Transcultural Context. Prior to his graduate studies, Mr. Funk worked for nearly a decade in education: as an ESL instructor and teacher trainer in New York City, and as a gym, math and English teacher in Barcelona. -

September 2009 Special Edition Language, Culture and Identity in Asia

The Linguistics Journal – September 2009 The Linguistics Journal September 2009 Special Edition Language, Culture and Identity in Asia Editors: Francesco Cavallaro, Andrea Milde, & Peter Sercombe The Linguistics Journal – Special Edition Page 1 The Linguistics Journal – September 2009 The Linguistics Journal September 2009 Special Edition Language, Culture and Identity in Asia Editors: Francesco Cavallaro, Andrea Milde, & Peter Sercombe The Linguistics Journal: Special Edition Published by the Linguistics Journal Press Linguistics Journal Press A Division of Time Taylor International Ltd Trustnet Chambers P.O. Box 3444 Road Town, Tortola British Virgin Islands http://www.linguistics-journal.com © Linguistics Journal Press 2009 This E-book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of the Linguistics Journal Press. No unauthorized photocopying All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of The Linguistics Journal. [email protected] Editors: Francesco Cavallaro, Andrea Milde, & Peter Sercombe Senior Associate Editor: Katalin Egri Ku-Mesu Journal Production Editor: Benjamin Schmeiser ISSN 1738-1460 The Linguistics Journal – Special Edition Page 2 The Linguistics Journal – September 2009 Table of Contents Foreword by Francesco Cavallaro, Andrea Milde, & Peter Sercombe………………………...... 4 - 7 1. Will Baker……………………………………………………………………………………… 8 - 35 -Language, Culture and Identity through English as a Lingua Franca in Asia: Notes from the Field 2. Ruth M.H. Wong …………………………………………………………………………….. 36 - 62 -Identity Change: Overseas Students Returning to Hong Kong 3. Jules Winchester……………………………………..………………………………………… 63 - 81 -The Self Concept, Culture and Cultural Identity: An Examination of the Verbal Expression of the Self Concept in an Intercultural Context 4. -

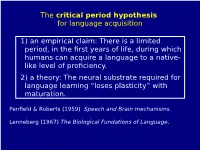

The Critical Period Hypothesis for Language Acquisition 1) an Empirical Claim: There Is a Limited Period, in the First Years Of

The critical period hypothesis for language acquisition 1) an empirical claim: There is a limited period, in the first years of life, during which humans can acquire a language to a native- like level of proficiency. 2) a theory: The neural substrate required for language learning “loses plasticity” with maturation. Penfield & Roberts (1959) Speech and Brain mechanisms. Lenneberg (1967) The Biological Fundations of Language. “Language acquisition circuitry is not needed once it has been used. It should be dismantled if keeping it around incurs any cost [...] Greedy neural tissue lying around beyond its point of usefulness is a good candidate for the recycling bin.” Pinker, 1994, The Language Instinct. Note that there several possible explanations: - maturationnal constraints (“loss of plasiticity”) - “use it then lose it” - “use it or lose it” (Tom Bever) Critical Periodes in Animals ● Effect of visual deprivation on ocular dominance – Hubel & Wiesel (1965) Comparison of the effects of unilateral and bilateral eye closure on cortical unit responses in kittens. J Neurophysiology. ● Song learning in sparrows – Marler & Peters (2010) A Sensitive Period for Song Acquisition in the Song Sparrow, Melospiza melodia: A Case of Age- limited Learning. Ethology ● Plasticity of auditory space map: – Knudsen EI, Knudsen PF (1990) Sensitive and critical periods for visual calibration of sound localization by barn owls. J Neurosci. Knudsen and Knudsen, 1990 ● Owls equipped with prismatic spectacles within the first month of life exhibited large adaptive shifts in auditory orienting behavior, whereas owls equipped with prisms as adults did not. ● The capacity of abnormal vision to alter sound localization declined to adult levels by 70–100 d of age. -

Linguistics 001 Final Exam

Linguisti cs 001 Final Exam This exam has three parts: a section of multiple choice questions, a section of short ll-in questions, and an essay. Each section counts the same towards the overall exam grade. Your SSN Your Name Part one Multiple choice question. Select only ONE answer for each question. 1. Two languages are considered to b e related memb ers of a \language family" (a) if the ma jority of memb ers of the sp eech communities involved are of the same biological sto ck. (b) if they develop ed by normal pro cesses of language change from a common ancestor. (c) if they share at least 50% of the words in their basic vo cabulary. (d) if their sound systems, word order and in ectional categories are essentially the same. 2. Language-related sex di erences in human biology concern (a) the larynx and the lips. (b) the striate cortex and the mobility of the tongue tip. (c) the corpus cal losum and the larynx. (d) the velum and the resonant cavities of the chest. 3. The typical numb er of displays in an animal's rep ertoire is said to b e (a) ab out 3 (b) ab out 30 (c) ab out 300 (d) ab out 3,000 (e) ab out 30,000 4. In a logographic writing system, the basic written units generally corresp ond to (a) phonemes (b) morphemes (c) concepts (d) sp eech acts 5. Metered verse primarily involves restrictions on which asp ects of language structure? (a) phonology (b) morphology (c) syntax (d) semantics (e) pragmatics 1 6. -

An Introduction to Linguistic Typology

An Introduction to Linguistic Typology An Introduction to Linguistic Typology Viveka Velupillai University of Giessen John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 the American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data An introduction to linguistic typology / Viveka Velupillai. â. p cm. â Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Typology (Linguistics) 2. Linguistic universals. I. Title. P204.V45 â 2012 415--dc23 2012020909 isbn 978 90 272 1198 9 (Hb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 1199 6 (Pb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 7350 5 (Eb) © 2012 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Company • P.O. Box 36224 • 1020 me Amsterdam • The Netherlands John Benjamins North America • P.O. Box 27519 • Philadelphia PA 19118-0519 • USA V. Velupillai: Introduction to Typology NON-PUBLIC VERSION: PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR DISSEMINATE!! ForFor AlTô VelaVela anchoranchor and and inspiration inspiration 2 Table of contents Acknowledgements xv Abbreviations xvii Abbreviations for sign language names xx Database acronyms xxi Languages cited in chapter 1 xxii 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Fast forward from the past to the present 1 1.2 The purpose of this book 3 1.3 Conventions 5 1.3.1 Some remarks on the languages cited in this book 5 1.3.2 Some remarks on the examples in this book 8 1.4 The structure of this book 10 1.5 Keywords 12 1.6 Exercises 12 Languages cited in chapter 2 14 2. -

Malebicta INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL of VERBAL AGGRESSION

MAlebicTA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF VERBAL AGGRESSION III . Number 2 Winter 1979 REINHOLD AMAN ," EDITOR -a· .,.'.""",t!. 1'''' ...... ".......... __... CD MALEDICTA PRESS WAUKESHA 196· - MALEDICTA III Animal metaphors: Shit linked with animal names means "I don't believe a word of it," as in pig, buzzard, hen, owl, whale, turtle, rat, cat, and bat shit, as well as the ever-popular horseshit. But bullshit remains the most favored, probably because of the prodigious quantity of functional droppings associated with the beast. On payday the eagle shits. Ill. Insults Shit on YDU!, eat shit!, go shit in your hat!, full ofshit, tough shit, shit-head (recall Lieutenant Scheisskopf in Catch-22), ELEMENTARY RUSSIAN OBSCENITY You shit, little shit, stupid shit, dumb shit, simple shit, shit heel; he don't know shit from Shinola, shit or get offthe pot, ·Boris Sukitch Razvratnikov chickenshit, that shit don't fetch, to be shit on, not worth diddly (or doodly) shit, don't know whether to shit orgo blind, he thinks his shit don't stink, he thinks he's King Shit, shit This article wiII concern itself with the pedagogical problems eating grin. encountered in attempting to introduce the basic concepts of IV: Fear Russian obscenity (mat) to English-speaking first-year students Scared shitless, scare the shit out of, shit green (or blue), shit at the college level. The essential problem is the fact that Rus .v,''' bricks, shit bullets, shit little blue cookies, shit out of luck, sian obscenity is primarily derivational while English (i.e., in 'r" almost shit in his pants (or britches), on someone's shit-list, this context, American) obscenity is analytic. -

FIRST LANGUAGE and SOCIOLINGUISTIC INFLUENCES on the SOUND PATTERNS of INDIAN ENGLISH by HEMA SIRSA a DISSERTATION Presented To

FIRST LANGUAGE AND SOCIOLINGUISTIC INFLUENCES ON THE SOUND PATTERNS OF INDIAN ENGLISH by HEMA SIRSA A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Linguistics and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Hema Sirsa Title: First Language and Sociolinguistic Influences on the Sound Patterns of Indian English This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Linguistics by: Melissa A. Redford Chairperson Vsevolod Kapatsinski Core Member Tyler Kendall Core Member Kaori Idemaru Institutional Representative and J. Andrew Berglund Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2014 ii © 2014 Hema Sirsa iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Hema Sirsa Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics December 2014 Title: First Language and Sociolinguistic Influences on the Sound Patterns of Indian English The current dissertation is a systematic study of variation in the English spoken in multilingual and multicultural India. Three experiments were conducted to investigate the influence of two native languages (Hindi and Telugu) on English, which is spoken by almost all Indians as a second language. The first experiment indicated that Indian English (IE) is accented by the first language of its speakers, but high English proficiency and the degree of divergence between the sound patterns of the speaker’s native language and his or her IE suggested that other factors might influence the preservation of a native language accent in IE. -

Investigating Learning English Strategies and English Needs of Undergraduate Students at the National University of Laos

English Language Teaching; Vol. 6, No. 10; 2013 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Investigating Learning English Strategies and English Needs of Undergraduate Students at the National University of Laos Thongma Souriyavongsa1, Mohamad Jafre Zainol Abidin1, Rany Sam1, Leong Lai Mei1 & Ithayaraj Britto Aloysius1 1 School of Educational Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia Correspondence: Thongma Souriyavongsa, PhD student at School of Educational Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800, Penang, Malaysia. Tel: 601-6690-9027. E-mail: [email protected] Received: June 16, 2013 Accepted: July 9, 2013 Online Published: September 4, 2013 doi:10.5539/elt.v6n10p57 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v6n10p57 Abstract This paper aims to investigate learning English strategies and the requirement of English needs of the undergraduate students at the National University of Laos (NUOL). The study employed a survey design which involved in administering questionnaires of rating scales, and adapting the items from (Barakat, 2010; Chengbin, 2008; Kathleen A, 2010; Patama, 2001; Richards, 2001), to measure learning English strategies and the needs of English skills from 160 Lao undergraduate students of NUOL. The findings of this study revealed that speaking skill was the most important skills that students needed to improve in their undergraduate program. All participants reported a medium frequency use of strategy on learning English. The most frequently used strategies involved in using -

English and Identity in Asia 1

ASIATIC, VOLUME 2, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2008 English and Identity in Asia 1 Richard F. Young 2 University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA Abstract A common assumption is that one’s mother tongue is essentially one’s ethnocultural identity. Contact by speakers of local languages with a hegemonic language such as English is therefore seen as endangering not only the local language but also threatening the identity that speakers deem closest to them. I will argue in this paper that identifying language with identity is an oversimplification. I present societal attitudes toward English in a number of East and Southeast Asian nations and discuss the roots of those attitudes. Macro-societal attitudes towards language are, however, only one factor in the construction of ethnocultural identity in face-to-face interaction. I borrow Bucholtz and Hall’s tactics of intersubjectivity to frame my case that personal identity is constructed and negotiated by language performance in oral and literate practices and it is neither determined nor fixed by the attitudes of a society toward languages. Keywords World Englishes, social identity, intersubjectivity, ethnicity, multilingualism, language planning Introduction A common assumption is that one’s mother tongue is essentially one’s ethnocultural identity. Contact by speakers of local languages with a hegemonic language such as English is therefore seen as endangering not only the local language but also 1 Plenary address to English and Asia: First International Conference on Language and Linguistics , International Islamic University Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, November 24-28, 2008. 2 Richard F. Young is Professor of English Linguistics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he teaches courses in Sociolinguistics, English Syntax, Language Acquisition, and Research Methods. -

Somali Dialects in the United States: How Intelligible Is Af-Maay to Speakers of Af-Maxaa? Deqa Hassan Minnesota State University - Mankato

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects 2011 Somali Dialects in the United States: How Intelligible is Af-Maay to Speakers of Af-Maxaa? Deqa Hassan Minnesota State University - Mankato Follow this and additional works at: http://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons Recommended Citation Hassan, Deqa, "Somali Dialects in the United States: How Intelligible is Af-Maay to Speakers of Af-Maxaa?" (2011). Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects. Paper 276. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Somali Dialects in the United States: How Intelligible is Af-Maay to Speakers of Af- Maxaa? By Deqa M. Hassan A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts In English: Teaching English as a Second Language Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota July 2011 ii Somali Dialects in the United States: How Intelligible is Af-Maay to Speakers of Af- Maxaa? Deqa M. Hassan This thesis has been examined and approved by the following members of the thesis committee. Dr. Karen Lybeck, Advisor Dr. Harry Solo iii ABSTRACT Somali Dialects in the United States: How Intelligible is Af-Maay to Speakers of Af-Maxaa? By Deqa M.