Historical Overview of Leprosy Control in Cuba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluación De Las Condiciones Ambientales De La Ciudad De Nuevitas Y Sus Alrededores* **Josefa PRIMELLES F.• ***Elsa RODR{GUEZ Y ****Luis RAMOS G

Evaluación de las condiciones ambientales de la ciudad de Nuevitas y sus alrededores* **Josefa PRIMELLES F.• ***Elsa RODR{GUEZ y ****Luis RAMOS G. RESUMEN. El impetuoso desarrollo industrial y demográfico expe rimentado por el territorio de Nuevitas, unido al inadecuado manejo de que fueron objeto muchos de sus recursos en la etapa colonial y seudorrepublicana, ha empezado a manifestarse negativamente en el met'io ambiente de la región. Los objetivos fundamentales del trabajo son hacer una evaluación preliminar de la calidad ambiental dentro de la ciudad de Nuevitas y del estado de conservac.ión del medio geográfico que la circunda, así como evaluar la situación perspectiva de la ciudad una vez instalados los electrofiltros de la fábrica de cewento "26 de Julio". Como expresión gráfica del trab�jo se obtu viemn: un mapa inventario de la problemática existente, un mapa donde aparecen categorizadas las distintas áreas del territorio según el grado de afectación y un mapa pronóstico de la calidad ambiental de la ciudad luego de la instalación de los electrofiltros antes men cionados. INTRODUCCIÓN El área de estudio comprende la península orillas .de la balúa del mismo nombre, una do11de se asienta ,la ciudad de Nuevitas y de las mayores bahías de boLsa del País. sus aguas adyacentes. Esta ciudad se encuentra ubicada en la costa nor.te de la Provincia de Camagüey, *Manuscrito aprobado en noviembre de 1987, a ¿os 21° 33' de latitud N y los 77°16' de **Grupo de Geografía de Camagüey, Academia longitud W, oon una población de 37 437 de Ciencias de Cuba. -

A History of Leprosy and Coercion in Hawai’I

THE PURSE SEINE AND EURYDICE: A HISTORY OF LEPROSY AND COERCION IN HAWAI’I A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ANTHROPOLOGY DECEMBER 2012 By David James Ritter Thesis Committee: Chairperson Eirik Saethre Geoffrey White Noelani Arista Keywords: Leprosy, Capitalism, Hansen’s Disease, Hawaiʻi, Molokaʻi, Kalaupapa, Political Economy, Medical Anthropology Acknowledgements I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to a number of individuals without whom this research would not have been possible. First, I would like to thank each of my committee members- Eirik Saethre, Geoff White, and Noelani Arista- for consistently finding time and energy to commit to my project. I would like to thank the staff and curators of the Asia Pacific collection at the Hamilton Library for their expertise University of Hawai`i at Mānoa. I would also like to thank my friend and office mate Aashish Hemrajani for consistently providing thought provoking conversation and excellent reading suggestions, both of which have in no small way influenced this thesis. Finally, I would like to extend my greatest gratitude to my parents, whose investment in me over the course this thesis project is nothing short of extraordinary. ii Abstract In 1865, the Hawai`i Board of Health adopted quarantine as the primary means to arrest the spread of leprosy in the Kingdom of Hawai`i. In Practice, preventing infection entailed the dramatic expansion of medical authority during the 19th century and included the establishment of state surveillance networks, the condemnation by physicians of a number of Hawaiian practices thought to spread disease, and the forced internment of mainly culturally Hawaiian individuals. -

Evidence for Mycobacterium Leprae Drug Resistance in a Large Cohort of Leprous Neuropathy Patients from India

Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 102(3), 2020, pp. 547–552 doi:10.4269/ajtmh.19-0390 Copyright © 2020 by The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Evidence for Mycobacterium leprae Drug Resistance in a Large Cohort of Leprous Neuropathy Patients from India Niranjan Prakash Mahajan,1 Mallika Lavania,2 Itu Singh,2 Saraswati Nashi,1 Veeramani Preethish-Kumar,1 Seena Vengalil,1 Kiran Polavarapu,1 Chevula Pradeep-Chandra-Reddy,1 Muddasu Keerthipriya,1 Anita Mahadevan,3 Tagaduru Chickabasaviah Yasha,3 Bevinahalli Nanjegowda Nandeesh,3 Krishnamurthy Gnanakumar,3 Gareth J. Parry,4 Utpal Sengupta,2 and Atchayaram Nalini1* 1Department of Neurology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India; 2Stanley Browne Research Laboratory, TLM Community Hospital, New Delhi, India; 3Department of Neuropathology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India; 4Department of Neurology, St John’s Medical College, Bangalore, India Abstract. Resistance to anti-leprosy drugs is on the rise. Several studies have documented resistance to rifampicin, dapsone, and ofloxacin in patients with leprosy. We looked for point mutations within the folP1, rpoB, and gyrA gene regions of the Mycobacterium leprae genome predominantly in the neural form of leprosy. DNA samples from 77 nerve tissue samples were polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified for MlepraeDNA and sequenced for drug resistance–determining regions of genes rpoB, folP1, and gyrA. The mean age at presentation and onset was 38.2 ±13.4 (range 14–71) years and 34.9 ± 12.6 years (range 10–63) years, respectively. The majority had borderline tuberculoid leprosy (53 [68.8%]). Mutations associated with resistance were identified in 6/77 (7.8%) specimens. -

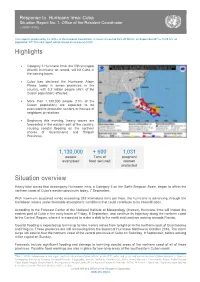

Highlights Situation Overview

Response to Hurricane Irma: Cuba Situation Report No. 1. Office of the Resident Coordinator ( 07/09/ 20176) This report is produced by the Office of the Resident Coordinator. It covers the period from 20:00 hrs. on September 06th to 14:00 hrs. on September 07th.The next report will be issued on or around 08/09. Highlights Category 5 Hurricane Irma, the fifth strongest Atlantic hurricane on record, will hit Cuba in the coming hours. Cuba has declared the Hurricane Alarm Phase today in seven provinces in the country, with 5.2 million people (46% of the Cuban population) affected. More than 1,130,000 people (10% of the Cuban population) are expected to be evacuated to protection centers or houses of neighbors or relatives. Beginning this evening, heavy waves are forecasted in the eastern part of the country, causing coastal flooding on the northern shores of Guantánamo and Holguín Provinces. 1,130,000 + 600 1,031 people Tons of pregnant evacuated food secured women protected Situation overview Heavy tidal waves that accompany Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, began to affect the northern coast of Cuba’s eastern provinces today, 7 September. With maximum sustained winds exceeding 252 kilometers (km) per hour, the hurricane is advancing through the Caribbean waters under favorable atmospheric conditions that could contribute to its intensification. According to the Forecast Center of the National Institute of Meteorology (Insmet), Hurricane Irma will impact the eastern part of Cuba in the early hours of Friday, 8 September, and continue its trajectory along the northern coast to the Central Region, where it is expected to make a shift to the north and continue moving towards Florida. -

Elisabeth Catherine Mentha Hill

The Roots of Persecution: a comparison of leprosy and madness in late medieval thought and society by Elisabeth Catherine Mentha Hill A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Department of History and Classics University of Alberta © Elisabeth Catherine Mentha Hill, 2016 Abstract This thesis compares madness and leprosy in the late Middle Ages. The first two chapters explore the conceptualization of madness and leprosy, finding that both were similarly moralized and associated with sin and spiritual degeneration. The third chapter examines the leper and the mad person as social identities and finds that, although leprosy and madness, as concepts, were treated very similarly, lepers and the mad received nearly opposite social treatment. Lepers were collectively excluded and institutionalized, while the mad were assessed and treated individually, and remained within their family and community networks. The exclusionary and marginalizing treatment of lepers culminated, in 1321, in two outbreaks of persecutory violence in France and Aragon, and in lesser but more frequent expulsions through the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The mad were not subject to comparable, collective violence. In light of the similar moral and spiritual content of leprosy and madness as concepts, this comparison indicates that a morally condemned or stigmatized condition was not sufficient to generate persecution, or to produce a persecuted social identity. It was the structure of the concept leprosy that produced a collective social identity available to the persecuting apparatus of late medieval society, while the fluid concept of madness produced the more individual identity of the mad person, which was less susceptible to the collective actions of persecution. -

550 Leprosy in China: a History. by Angela Ki-Che Leung. New York

550 Book Reviews / T’oung Pao 96 (2011) 543-585 Leprosy in China: A History. By Angela Ki-che Leung. New York: Columbia Uni- versity Press, 2009. 373 pp. Index, bibliography, ill. Angela Leung’s new book adds a very important case study that historicizes the recent “modernist” works on the history of public health in China by Ruth Rogaski,1 Carol Benedict,2 and Kerrie Macpherson.3 Unlike the above three works, which all focus on “modernity” and have rightly been well-received, Leung presents a highly original, postcolonial history of leprosy in China, which was known in antiquity as li/lai, wind-induced skin ailments, or mafeng, “numb skin.” ese symptoms were subsequently combined during the Song dynasty into a single etiology of skin ailments , i.e., dafeng/lai. Leung’s pioneering account successfully provincializes the European narrative of leprosy and public health by presenting: 1) the longer historical memory of “leprosy” in China since antiquity; 2) the important public health changes that occurred during the Song dynasty (960-1280); and 3) how the skin illnesses we call leprosy were reconceptualized during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Leung then concludes her manuscript with two fi nal chapters that successfully parallel but revise the accounts in Rogaski, Benedict, and Macpherson. Leung describes Chinese political eff orts since the nineteenth century to develop not simply a “modern” and “Western” medical regime but a “hybrid,” Sino-Western public health system to deal with the disease. e book reveals overall the centrality of China in the history of the leprosy, and it shows how leprosy played out as a global threat, which provides lessons for dealing with AIDS, SARS, and bird viruses today. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 188/Monday, September 28, 2020

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 188 / Monday, September 28, 2020 / Notices 60855 comment letters on the Proposed Rule Proposed Rule Change and to take that the Secretary of State has identified Change.4 action on the Proposed Rule Change. as a property that is owned or controlled On May 21, 2020, pursuant to Section Accordingly, pursuant to Section by the Cuban government, a prohibited 19(b)(2) of the Act,5 the Commission 19(b)(2)(B)(ii)(II) of the Act,12 the official of the Government of Cuba as designated a longer period within which Commission designates November 26, defined in § 515.337, a prohibited to approve, disapprove, or institute 2020, as the date by which the member of the Cuban Communist Party proceedings to determine whether to Commission should either approve or as defined in § 515.338, a close relative, approve or disapprove the Proposed disapprove the Proposed Rule Change as defined in § 515.339, of a prohibited Rule Change.6 On June 24, 2020, the SR–NSCC–2020–003. official of the Government of Cuba, or a Commission instituted proceedings For the Commission, by the Division of close relative of a prohibited member of pursuant to Section 19(b)(2)(B) of the Trading and Markets, pursuant to delegated the Cuban Communist Party when the 7 Act, to determine whether to approve authority.13 terms of the general or specific license or disapprove the Proposed Rule J. Matthew DeLesDernier, expressly exclude such a transaction. 8 Change. The Commission received Assistant Secretary. Such properties are identified on the additional comment letters on the State Department’s Cuba Prohibited [FR Doc. -

Orientación Familiar Para Educar En La Conservación De La Biodiversidad

Monteverdia, RNPS: 2189, ISSN: 2077-2890, 10(2), pp. 55-72, julio-diciembre 2017 Centro de Estudios de Gestión Ambiental. Universidad de Camagüey “Ignacio Agramonte Loynaz”. Camagüey. Cuba Las palmas en la provincia Camagüey-I: inventario preliminar1 The palms in the province Camagüey-I: preliminary inventory Rafael Risco Villalobos1, Celio Moya López2, Raúl Marcelino Verdecia Pérez3, Duanny Suárez Oropesa2 y Milián Rodríguez Lima2. 1 Estación Experimental Agroforestal Camagüey, Camagüey. Cuba. 2 Sociedad Cubana de Botánica. Cuba. 3 Jardín Botánico Cupainicú, Granma. Cuba. e-mail: [email protected] ______________________ Recibido: 19 de enero de 2017. Aceptado: 23 de febrero de 2017. Resumen El objetivo del artículo es actualizar el listado y la nomenclatura de las palmas de la provincia Camagüey, con la cuantificación del endemismo del grupo en el territorio. La información se obtuvo a partir del estudio de materiales de herbario, la revisión bibliográfica y observaciones de campo. Ello permitió verificar la presencia de 33 taxones infragenéricos, pertenecientes a 9 géneros de la familia Arecaceae. Se reportan además dos especies pendientes de verificación. Los géneros mejor representados son: Copernicia con 15 taxones y Coccothrinax con 9. El 76 % del total son endémicas, de ellas 7 estrictas del territorio. Para cada taxón se informa: la nomenclatura científica y los sinónimos usados en Cuba, su distribución general y por municipios, así como las evidencias que la respaldan. Palabras clave: Arecaceae, checklist, flora, palmas de Camagüey. Summary The objective of the article is to update the list and the nomenclature of the palms of the province of Camagüey, with the quantification of the endemism of the group in the 1 En la elaboración del inventario que se presenta, posee un papel fundamental la experiencia en el trabajo de campo de sus autores y su grado de especialización en los estudios sobre palmas. -

Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba Subject

United Nations Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba From: Office of the Resident Coordinator in Cuba Subject: Situation Report No. 6 “Hurricane IKE”- September 16, 2008- 18:00 hrs. Situation: A report published today, September 16, by the official newspaper Granma with preliminary data on the damages caused by hurricanes GUSTAV and IKE asserts that they are estimated at 5 billion USD. The data provided below is a summary of official data. Pinar del Río Cienfuegos 25. Ciego de Ávila 38. Jesús Menéndez 1. Viñales 14. Aguada de Pasajeros 26. Baraguá Holguín 2. La palma 15. Cumanayagua Camagüey 39. Gibara 3. Consolación Villa Clara 27. Florida 40. Holguín 4. Bahía Honda 16. Santo Domingo 28. Camagüey 41. Rafael Freyre 5. Los palacios 17. Sagüa la grande 29. Minas 42. Banes 6. San Cristobal 18. Encrucijada 30. Nuevitas 43. Antilla 7. Candelaria 19. Manigaragua 31. Sibanicú 44. Mayarí 8. Isla de la Juventud Sancti Spíritus 32. Najasa 45. Moa Matanzas 20. Trinidad 33. Santa Cruz Guantánamo 9. Matanzas 21. Sancti Spíritus 34. Guáimaro 46. Baracoa 10. Unión de Reyes 22. La Sierpe Las Tunas 47. Maisí 11. Perico Ciego de Ávila 35. Manatí 12. Jagüey Grande 23. Managua 36. Las Tunas 13. Calimete 24. Venezuela 37. Puerto Padre Calle 18 No. 110, Miramar, La Habana, Cuba, Apdo 4138, Tel: (537) 204 1513, Fax (537) 204 1516, [email protected], www.onu.org.cu 1 Cash donations in support of the recovery efforts, can be made through the following bank account opened by the Government of Cuba: Account Number: 033473 Bank: Banco Financiero Internacional (BFI) Account Title: MINVEC Huracanes restauración de daños Measures adopted by the Government of Cuba: The High Command of Cuba’s Civil Defense announced that it will activate its centers in all of Cuba to direct the rehabilitation of vital services that have been disrupted by the impact of Hurricanes GUSTAV and IKE. -

Infografía De La Ruta Camagüeyana De Fidel

, yy y q FidelVariada es insustituible”. CAMAGÜEY,CAMAGÜEY, SÁBADO 19 DE 13 SEPTIEMBRE DE AGOSTO DE DEL 2015 2016 CAMAGÜEY, SÁBADO 13 DE AGOSTO DEL 2016 está pasando al doblar de la esquina. 5 4 General de Ejército Raúl Castro Ruz Raúl Roa García (Intelectual y político (Presidente de la República de Cuba) cubano) Ruta camagüeyana de Fidel Enero 4: Entrada de la Caravana de la Libertad a la ciudad de Camagüey. Esa noche Abril 5: En el corte de caña en Vertientes. el Comandante en Jefe pronuncia su primer discurso ante miles de agramontinos Enero 13: Recorrido en compañía concentrados en la Plaza de la Libertad. Hace su intervención, de contenido pro- Septiembre 9: Por varios días recorre la entonces provincia del presidente de Panamá Omar gramático, desde el balcón de la actual escuela secundaria básica Noel Fernández. de Camagüey: Isla de Turiguanó, Loma de Cunagua, y Torrijos, por la ciudad cabece- granja del pueblo Manuel Sanguily, de la actual Ciego Febrero 6: Encuentro con los estudiantes del Instituto de Segunda Enseñanza en el ra y el central Panamá, en Noviembre 27 Y 28: Inaugura la Planta Mecá- de Ávila; en el hoy municipio de Sierra de Cubitas aeropuerto Ignacio Agramonte. Vertientes. nica Mayor General Ignacio Agramonte y ade- estuvo en Pozo de Vilató, durmió en la escuela Con- Mayo 24 y 25: Recorre más visita la comunidad del EJT Combate de Marzo 19: Preside en la ciudad de Camagüey un acto de impulso a la aplicación de rado Benítez y Paso de Lesca.También en los alre- la circunvalación norte, La Sacra. -

State of Ambiguity: Civic Life and Culture in Cuba's First Republic

STATE OF AMBIGUITY STATE OF AMBIGUITY CiviC Life and CuLture in Cuba’s first repubLiC STEVEN PALMER, JOSÉ ANTONIO PIQUERAS, and AMPARO SÁNCHEZ COBOS, editors Duke university press 2014 © 2014 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-f ree paper ♾ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data State of ambiguity : civic life and culture in Cuba’s first republic / Steven Palmer, José Antonio Piqueras, and Amparo Sánchez Cobos, editors. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5630-1 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5638-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Cuba—History—19th century. 2. Cuba—History—20th century. 3. Cuba—Politics and government—19th century. 4. Cuba—Politics and government—20th century. 5. Cuba— Civilization—19th century. 6. Cuba—Civilization—20th century. i. Palmer, Steven Paul. ii. Piqueras Arenas, José A. (José Antonio). iii. Sánchez Cobos, Amparo. f1784.s73 2014 972.91′05—dc23 2013048700 CONTENTS Introduction: Revisiting Cuba’s First Republic | 1 Steven Palmer, José Antonio Piqueras, and Amparo Sánchez Cobos 1. A Sunken Ship, a Bronze Eagle, and the Politics of Memory: The “Social Life” of the USS Maine in Cuba (1898–1961) | 22 Marial Iglesias Utset 2. Shifting Sands of Cuban Science, 1875–1933 | 54 Steven Palmer 3. Race, Labor, and Citizenship in Cuba: A View from the Sugar District of Cienfuegos, 1886–1909 | 82 Rebecca J. Scott 4. Slaughterhouses and Milk Consumption in the “Sick Republic”: Socio- Environmental Change and Sanitary Technology in Havana, 1890–1925 | 121 Reinaldo Funes Monzote 5. -

I LEPROSY in ANCIENT INDIAN MEDICINE by Leprosy Is Known To

i LEPROSY IN ANCIENT INDIAN MEDICINE by DHARMENDRA, M.B.B.S., D.B. L eprosy Depa;rtment, Sc}wol of Tropical Med'icine, Calcutta INTRODUCTION Leprosy is known to have been prevalent since ancient times in India, China, and Africa, and it was prevalent in the middle ages in Europe. Statements have often been made to the effect that references to leprosy are found in the ancient literatures of these countries. In India, the term "Kushtha" occurring in the Vedas has been believed by some workers to relate to leprosy. In China there is no definite reference to the existence of leprosy in the ancient literature of the country, but there is a tradition that a disciple of Confucius died of leprosy about 600 B.C. A reference to leprosy is believed to have been made in an Egyptian record of 1350 B.C. describing the occurrence of leprosy among the Negro slaves from Sudan and it has often been stated that leprosy has been described under the term "Uchedu" in the "Ebers Papyrus" writ ten about 1550 B.C. Several workers have stated th~t a reference to leprosy is found in the Bible; the term "Zaraath" of the Old Tes tament and "Lepra" of the New Testament have been considered to refer to leprosy. The difficulty in accepting most of these statements lies in the fact that the references in question either do not contain any clin ical description or the description does not correspond to leprosy as we know it today. There is no mention of numbness or of loss of skin sensation, or of manifestations of the nodular type of lep rosy.