Status and Conservation of Manatees in Cuba: Historical Observations and Recent Insights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluación De Las Condiciones Ambientales De La Ciudad De Nuevitas Y Sus Alrededores* **Josefa PRIMELLES F.• ***Elsa RODR{GUEZ Y ****Luis RAMOS G

Evaluación de las condiciones ambientales de la ciudad de Nuevitas y sus alrededores* **Josefa PRIMELLES F.• ***Elsa RODR{GUEZ y ****Luis RAMOS G. RESUMEN. El impetuoso desarrollo industrial y demográfico expe rimentado por el territorio de Nuevitas, unido al inadecuado manejo de que fueron objeto muchos de sus recursos en la etapa colonial y seudorrepublicana, ha empezado a manifestarse negativamente en el met'io ambiente de la región. Los objetivos fundamentales del trabajo son hacer una evaluación preliminar de la calidad ambiental dentro de la ciudad de Nuevitas y del estado de conservac.ión del medio geográfico que la circunda, así como evaluar la situación perspectiva de la ciudad una vez instalados los electrofiltros de la fábrica de cewento "26 de Julio". Como expresión gráfica del trab�jo se obtu viemn: un mapa inventario de la problemática existente, un mapa donde aparecen categorizadas las distintas áreas del territorio según el grado de afectación y un mapa pronóstico de la calidad ambiental de la ciudad luego de la instalación de los electrofiltros antes men cionados. INTRODUCCIÓN El área de estudio comprende la península orillas .de la balúa del mismo nombre, una do11de se asienta ,la ciudad de Nuevitas y de las mayores bahías de boLsa del País. sus aguas adyacentes. Esta ciudad se encuentra ubicada en la costa nor.te de la Provincia de Camagüey, *Manuscrito aprobado en noviembre de 1987, a ¿os 21° 33' de latitud N y los 77°16' de **Grupo de Geografía de Camagüey, Academia longitud W, oon una población de 37 437 de Ciencias de Cuba. -

Belize—A Last Stronghold for Manatees in the Caribbean

Belize—a last stronghold for manatees in the Caribbean Thomas J. O'Shea and Charles A. 'Lex' Salisbury Belize is a small country but it offers a safe haven for the largest number of manatees in the Caribbean. The authors' survey in 1989 revealed that there has been no apparent decline since the last study in 1977. However, there is no evidence for population growth either and as the Belize economy develops threats from fisheries, human pressure and declining habitat quality will increase. Recommendations are made to ensure that Belize safeguards its manatee populations. Introduction extensive (Figure 1): straight-line distance from the Rio Hondo at the northern border The West Indian manatee Trichechus manatus with Mexico to the Rio Sarstoon at the is listed as endangered by the US Fish and Guatemala boundary is about 290 km. Wildlife Service and as vulnerable to extinc- However, studies reported 10-20 years ago tion by the International Union for suggested that manatee populations may have Conservation of Nature and Natural been high in Belize relative to other Resources (IUCN) (Thornback and Jenkins, Caribbean-bordering countries (Charnock- 1982). A long-lived, slowly reproducing, her- Wilson, 1968, 1970; Charnock-Wilson et al, bivorous marine mammal, the West Indian 1974; Bengtson and Magor, 1979). Despite manatee inhabits coastal waters and slow- Belize's possible importance for manatees, moving rivers of the tropical and subtropical additional status surveys have not been western Atlantic. This species first became attempted there since 1977 (Bengtson and known in Europe from records made in the Magor, 1979). We made aerial counts of mana- Caribbean on the voyages of Christopher tees over selected areas in May 1989, and dis- Columbus (Baughman, 1946). -

West Indian Manatee (Trichechus Manatus) Habitat Characterization Using Side-Scan Sonar

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Master's Theses Graduate Research 2017 West Indian Manatee (Trichechus Manatus) Habitat Characterization Using Side-Scan Sonar Mindy J. McLarty Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation McLarty, Mindy J., "West Indian Manatee (Trichechus Manatus) Habitat Characterization Using Side-Scan Sonar" (2017). Master's Theses. 98. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses/98 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT WEST INDIAN MANATEE (TRICHECHUS MANATUS) HABITAT CHARACTERIZATION USING SIDE-SCAN SONAR by Mindy J. McLarty Chair: Daniel Gonzalez-Socoloske ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Thesis Andrews University School of Arts and Sciences Title: WEST INDIAN MANATEE (TRICHECHUS MANATUS) HABITAT CHARACTERIZATION USING SIDE-SCAN SONAR Name of researcher: Mindy J. McLarty Name and degree of faculty chair: Daniel Gonzalez-Socoloske, Ph.D. Date completed: April 2017 In this study, the reliability of low cost side-scan sonar to accurately identify soft substrates such as grass and mud was tested. Benthic substrates can be hard to classify from the surface, necessitating an alternative survey approach. A total area of 11.5 km2 was surveyed with the sonar in a large, brackish mangrove lagoon system. Individual points were ground-truthed for comparison with the sonar recordings to provide a measure of accuracy. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article Journal's Webpage in Redalyc.Org Scientific Information System Re

Cultivos Tropicales ISSN: 1819-4087 Ediciones INCA Benítez-Fernández, Bárbara; Crespo-Morales, Anaisa; Casanova, Caridad; Méndez-Bordón, Aliek; Hernández-Beltrán, Yaima; Ortiz- Pérez, Rodobaldo; Acosta-Roca, Rosa; Romero-Sarduy, María Isabel Impactos de la estrategia de género en el sector agropecuario, a través del Proyecto de Innovación Agropecuaria Local (PIAL) Cultivos Tropicales, vol. 42, no. 1, e04, 2021, January-March Ediciones INCA DOI: https://doi.org/10.1234/ct.v42i1.1578 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=193266707004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Cultivos Tropicales, 2021, vol. 42, no. 1, e04 enero-marzo ISSN impreso: 0258-5936 Ministerio de Educación Superior. Cuba ISSN digital: 1819-4087 Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Agrícolas http://ediciones.inca.edu.cu Original article Impacts of the gender strategy in the agricultural sector, through the Local Agricultural Innovation Project (PIAL) Bárbara Benítez-Fernández1* Anaisa Crespo-Morales2 Caridad Casanova3 Aliek Méndez-Bordón4 Yaima Hernández-Beltrán5 Rodobaldo Ortiz-Pérez1 Rosa Acosta-Roca1 María Isabel Romero-Sarduy6 1Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Agrícolas (INCA), carretera San José-Tapaste, km 3½, Gaveta Postal 1, San José de las Lajas, Mayabeque, Cuba. CP 32 700 2Policlínico Docente “Pedro Borrás Astorga”, Calle Comandante Cruz # 70, La Palma, Pinar del Río, Cuba 3Universidad de Cienfuegos “Carlos Rafael Rodríguez”, carretera a Rodas, km 3 ½, Cuatro Caminos, Cienfuegos, Cuba 4Universidad Las Tunas, Centro Universitario Municipal “Jesús Menéndez”, calle 28 # 33, El Cenicero, El batey, Jesús Menéndez, Las Tunas, Cuba 5Universidad de Sancti Spíritus “José Martí Pérez”. -

Artemisa & Mayabeque Provinces

File10-artemisa-mayabequ-loc-cub6.dwg Book Initial Mapping Date Road Cuba 6 AndrewS May 2011 Scale All key roads labelled?Hierarchy Hydro ChapterArtemisa-Mayabequ Editor Cxns Date Title Spot colours removed?Hierarchy Symbols Author MC Cxns Date Nthpt Masking in Illustrator done? ? Book Off map Inset/enlargement correct?dest'ns BorderLocator A1 Key none Author Cxns Date Notes Basefile Final Ed Cxns Date KEY FORMAT SETTINGS New References Number of Rows (Lines) Editor Check Date MC Check Date Column Widths and Margins MC/CC Signoff Date ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd a rtemisa & Mayabeque p%047 r / poovincesp 883,838 Why Go? Artemisa Province. 144 Glancing from your window as you leave Havana, you will San Antonio de los see a flat, fertile plain stretching away from the capital. As Baños ..............144 far as the eye can see – west to the mountainous Sierra Artemisa ...........145 de Rosario and east to Matanzas province’s wildlife-rich Soroa ..............146 swamps – spreads a patchwork of dusty farmland and cheerful one-horse towns and hamlets. Travel-wise this has Las Terrazas ........148 been bypassed by tourists, and has instead long been the Bahía Honda ........ 151 bastion of weekending habaneros (Havana folk). Mayabeque Province 151 This could – possibly – be changing. Formerly Havana Playa Jibacoa .......152 province, this region was has been redefined in 2011 as the Jaruco .............155 all-new dual provinces of Artemisa and Mayabeque. Artemisa’s big draw is Cuba’s gorgeously situated eco- Surgidero de capital, Las Terrazas. Mayabeque beckons with beaches Batabanó ...........155 of Varadero-quality sand (without the crowds), and one of Cuba’s greatest train journeys: the delightful Hershey train, which traverses the gentle, lolling countryside to Matanzas. -

Historical Overview of Leprosy Control in Cuba

Review Article Historical Overview of Leprosy Control in Cuba Enrique Beldarraín-Chaple MD PhD ABSTRACT Program was established in 1962, implemented in 1963 and revised INTRODUCTION Leprosy, an infectious disease caused by Myco- fi ve times. In 1972, leper colonies were closed and treatment became bacterium leprae, affects the nervous system, skin, internal organs, ambulatory. In 1977, rifampicin was introduced. In 1988, the Program instituted controlled, decentralized, community-based multidrug treat- extremities and mucous membranes. Biological, social and environ- ment and established the criteria for considering a patient cured. In 2003, mental factors infl uence its occurrence and transmission. The fi rst it included actions aimed at early diagnosis and prophylactic treatment of effective treatments appeared in 1930 with the development of dap- contacts. Since 2008, it prioritizes actions directed toward the population sone, a sulfone. The main components of a control and elimination at risk, maintaining fi ve-year followup with dermatological and neurologi- strategy are early case detection and timely administration of multi- cal examination. Primary health care carries out diagnostic and treatment drug therapy. activities. The lowest leprosy incidence of 1.6 per 100,000 population was achieved in 2006. Since 2002, prevalence has remained steady at OBJECTIVES Review the history of leprosy control in Cuba, empha- 0.2 per 10,000 population. Leprosy ceased to be considered a public sizing particularly results of the National Leprosy Control Program, its health problem in Cuba as of 1993. In 1990–2015, 1.6% of new leprosy modifi cations and infl uence on leprosy control. patients were aged <15 years. -

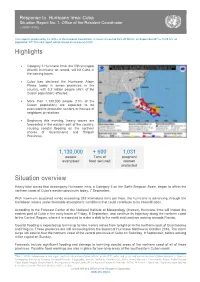

Highlights Situation Overview

Response to Hurricane Irma: Cuba Situation Report No. 1. Office of the Resident Coordinator ( 07/09/ 20176) This report is produced by the Office of the Resident Coordinator. It covers the period from 20:00 hrs. on September 06th to 14:00 hrs. on September 07th.The next report will be issued on or around 08/09. Highlights Category 5 Hurricane Irma, the fifth strongest Atlantic hurricane on record, will hit Cuba in the coming hours. Cuba has declared the Hurricane Alarm Phase today in seven provinces in the country, with 5.2 million people (46% of the Cuban population) affected. More than 1,130,000 people (10% of the Cuban population) are expected to be evacuated to protection centers or houses of neighbors or relatives. Beginning this evening, heavy waves are forecasted in the eastern part of the country, causing coastal flooding on the northern shores of Guantánamo and Holguín Provinces. 1,130,000 + 600 1,031 people Tons of pregnant evacuated food secured women protected Situation overview Heavy tidal waves that accompany Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, began to affect the northern coast of Cuba’s eastern provinces today, 7 September. With maximum sustained winds exceeding 252 kilometers (km) per hour, the hurricane is advancing through the Caribbean waters under favorable atmospheric conditions that could contribute to its intensification. According to the Forecast Center of the National Institute of Meteorology (Insmet), Hurricane Irma will impact the eastern part of Cuba in the early hours of Friday, 8 September, and continue its trajectory along the northern coast to the Central Region, where it is expected to make a shift to the north and continue moving towards Florida. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 188/Monday, September 28, 2020

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 188 / Monday, September 28, 2020 / Notices 60855 comment letters on the Proposed Rule Proposed Rule Change and to take that the Secretary of State has identified Change.4 action on the Proposed Rule Change. as a property that is owned or controlled On May 21, 2020, pursuant to Section Accordingly, pursuant to Section by the Cuban government, a prohibited 19(b)(2) of the Act,5 the Commission 19(b)(2)(B)(ii)(II) of the Act,12 the official of the Government of Cuba as designated a longer period within which Commission designates November 26, defined in § 515.337, a prohibited to approve, disapprove, or institute 2020, as the date by which the member of the Cuban Communist Party proceedings to determine whether to Commission should either approve or as defined in § 515.338, a close relative, approve or disapprove the Proposed disapprove the Proposed Rule Change as defined in § 515.339, of a prohibited Rule Change.6 On June 24, 2020, the SR–NSCC–2020–003. official of the Government of Cuba, or a Commission instituted proceedings For the Commission, by the Division of close relative of a prohibited member of pursuant to Section 19(b)(2)(B) of the Trading and Markets, pursuant to delegated the Cuban Communist Party when the 7 Act, to determine whether to approve authority.13 terms of the general or specific license or disapprove the Proposed Rule J. Matthew DeLesDernier, expressly exclude such a transaction. 8 Change. The Commission received Assistant Secretary. Such properties are identified on the additional comment letters on the State Department’s Cuba Prohibited [FR Doc. -

Orientación Familiar Para Educar En La Conservación De La Biodiversidad

Monteverdia, RNPS: 2189, ISSN: 2077-2890, 10(2), pp. 55-72, julio-diciembre 2017 Centro de Estudios de Gestión Ambiental. Universidad de Camagüey “Ignacio Agramonte Loynaz”. Camagüey. Cuba Las palmas en la provincia Camagüey-I: inventario preliminar1 The palms in the province Camagüey-I: preliminary inventory Rafael Risco Villalobos1, Celio Moya López2, Raúl Marcelino Verdecia Pérez3, Duanny Suárez Oropesa2 y Milián Rodríguez Lima2. 1 Estación Experimental Agroforestal Camagüey, Camagüey. Cuba. 2 Sociedad Cubana de Botánica. Cuba. 3 Jardín Botánico Cupainicú, Granma. Cuba. e-mail: [email protected] ______________________ Recibido: 19 de enero de 2017. Aceptado: 23 de febrero de 2017. Resumen El objetivo del artículo es actualizar el listado y la nomenclatura de las palmas de la provincia Camagüey, con la cuantificación del endemismo del grupo en el territorio. La información se obtuvo a partir del estudio de materiales de herbario, la revisión bibliográfica y observaciones de campo. Ello permitió verificar la presencia de 33 taxones infragenéricos, pertenecientes a 9 géneros de la familia Arecaceae. Se reportan además dos especies pendientes de verificación. Los géneros mejor representados son: Copernicia con 15 taxones y Coccothrinax con 9. El 76 % del total son endémicas, de ellas 7 estrictas del territorio. Para cada taxón se informa: la nomenclatura científica y los sinónimos usados en Cuba, su distribución general y por municipios, así como las evidencias que la respaldan. Palabras clave: Arecaceae, checklist, flora, palmas de Camagüey. Summary The objective of the article is to update the list and the nomenclature of the palms of the province of Camagüey, with the quantification of the endemism of the group in the 1 En la elaboración del inventario que se presenta, posee un papel fundamental la experiencia en el trabajo de campo de sus autores y su grado de especialización en los estudios sobre palmas. -

Antillean Manatee Trichechus Manatus Manatus Belize

Antillean Manatee Trichechus manatus manatus Belize Compiler: Jamal Galves Contributors: Jamal Galves, Joel Verde, Celia Mahung Suggested citation: Galves, J, Belize National Manatee Working Group and Verde, J. A. 2020. A Survival Blueprint for the Antillean Mantees Trichechus manatus manatus of Belize. Results from the EDGE PhotoArk NatGeo Fellowship Project: Efforts to Safeguard the Antillean Manatees of Belize. EDGE of Existence Programme, Zoological Society of London. 1. STATUS REVIEW 1.1 Taxonomy: The West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus), is from the order of the sirenian of the Trichechidae family and is divided into two subspecies: the Florida manatee T. m. latirostris; and the Antillean manatee T. m. manatus (Hatt, 1934). Antillean Manatee Florida Manatee Kingdom: Animalia Kingdom: Animalia Order: Sirenia Order: Sirenia Phylum: Chordata Phylum: Chordata Family: Trichechidae Family: Trichechidae Class: Mammalia Class: Mammalia Genus: Trichechus Genus: Trichechus Species: Trichechus manatus manatus Species: Trichechus manatus ssp. latirostris 1.2 Distribution and population status: Figure 1. Map of Antillean and Florida manatee distribution. Dark grey area shows the distribution of Antillean manatee Trichechus manatus manatus. The distribution of the Florida manatee is displayed in diagonal lines, and the known subpopulations of Antillean manatee with the species genetic barriers is demarcated with dotted lines, according to Vianna et al., 2006. Map used from Castelblanco-Martínez et al 2012. The Antillean Manatee has a fragmented distribution that ranges from the southeast of Texas to as far as the northeast of Brazil, including the Greater Antilles (Lefebvre et al., 2001; Reynolds and Powell, 2002). This species can be found in coastal marine, brackish and freshwater systems, and is capable to alternate between these three environments (Lefebvre, 2001). -

Portfolio of Opportunities for Foreign Investment 2018 - 2019

PORTFOLIO OF OPPORTUNITIES FOR FOREIGN INVESTMENT 2018 - 2019 INCLUDES TERRITORIAL DISTRIBUTION MINISTERIO DEL COMERCIO EXTERIOR Y LA INVERSIÓN EXTRANJERA PORTFOLIO OF OPPORTUNITIES FOR FOREIGN INVESTMENT 2018-2019 X 13 CUBA: A PLACE TO INVEST 15 Advantages of Investing in Cuba 16 Foreign Investment in Cuba 16 Foreign Investment in Figures 17 General Foreign Investment Policy Principles 19 Foreign Investment with agricultural cooperatives as partners X 25 FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES BY SECTOR X27 STRATEGIC CORE PRODUCTIVE TRANSFORMATION AND INTERNATIONAL INSERTION 28 Mariel Special Development Zone X BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES IN ZED MARIEL X 55 STRATEGIC CORE INFRASTRUCTURE X57 STRATEGIC SECTORS 58 Construction Sector X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS 70 Electrical Energy Sector 71 Oil X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS 79 Renewable Energy Sources X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS 86 Telecommunications, Information Technologies and Increased Connectivity Sector 90 Logistics Sector made up of Transportation, Storage and Efficient Commerce X245 OTHER SECTORS AND ACTIVITIES 91 Transportation Sector 246 Mining Sector X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS 99 Efficient Commerce 286 Culture Sector X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS 102 Logistics Sector made up of Water and Sanitary Networks and Installations 291 Actividad Audiovisual X FOREIGN INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY SPECIFICATIONS X -

Endangered Species Biological Assessment Technical Memorandum for the All Aboard Florida Passenger Rail Project West Palm Beach to Miami, Florida August 1, 2012

Endangered Species Biological Assessment Technical Memorandum for the All Aboard Florida Passenger Rail Project West Palm Beach to Miami, Florida August 1, 2012 ENDANGERED SPECIES BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT TECHNICAL MEMORADUM FOR THE ALL ABOARD FLORIDA PASSENGER RAIL PROJECT WEST PALM BEACH TO MIAMI, FLORIDA Prepared Pursuant to Section 7 (c) of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended by the Federal Railroad Administration and All Aboard Florida The following persons may be contacted for information on the Environmental Assessment: Catherine Dobbs Federal Railroad Administration 1200 New Jersey Ave, SE Washington, DC 20590 202.493.6347 Margarita Martinez Miguez All Aboard Florida 2855 Le Jeune Road, 4th Floor Coral Gables, Florida 33134 305.520.2458 Endangered Species Biological Assessment Technical Memorandum for the All Aboard Florida Passenger Rail Project West Palm Beach to Miami, Florida August 1, 2012 Table of Contents Section Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 ALTERNATIVE DEVELOPMENT .......................................................................................................... 3 2.1 No-Build Alternative ........................................................................................................... 3 2.2 System Build Alternative ..................................................................................................... 4 2.3 Station Alternatives ...........................................................................................................