Assessment of the Effect of the Acpc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Data Collection Survey for Strategy Development of Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Sector in the Republic of the Philippines

THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DATA COLLECTION SURVEY FOR STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT OF DISASTER RISK REDUCTION AND MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES FINAL REPORT FEBRUARY 2017 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS GLOBAL CO., LTD. CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. 1R PACIFIC CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. JR 17-021 THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DATA COLLECTION SURVEY FOR STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT OF DISASTER RISK REDUCTION AND MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES FINAL REPORT FEBRUARY 2017 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS GLOBAL CO., LTD. CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. PACIFIC CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. Data Collection Survey for Strategy Development of Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Sector in the Republic of the Philippines Summary Background and Objectives: The JICA cooperation strategy on DRRM formulated in 2008 included the promotion of non-structural measures such as the support for policy making and community enhancement based on the Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA) adopted in 2005 into the conventional cooperation projects mainly focusing on the implementation of structural measures. Since then, both Japan and the Philippines have experienced catastrophic disasters such as the Great East Japan Earthquake and Typhoon Yolanda, and both countries undertook efforts to respond and rebuild from unexpected and extraordinary disasters. Other countries have also experienced several catastrophic disasters, and new frameworks such as the Sendai Framework for DRR (SFDRR) were agreed and some targets to achieve their goals are being discussed through recently conducted international dialogues. From those international trends, several well-known keywords arose such as “Mainstreaming DRR” and “Build Back Better: BBB” which were originally used in Japan. -

View/Download PDF File of Power Development Plan 2016-2040

ABOUT THE COVER POWERING THE NATION This Power Development Plan serves as the path in powering the nation from 2016 and beyond. The cover depicts the invaluable role of the electric power industry in fuelling and sustaining the country’s economic growth and development. The Department of Energy (DOE) envisions for the Philippine energy industry to be globally competitive in utilizing energy in Filipino communities through clean, efficient, robust and sustainable systems in order to create wealth and transform the lives of the Filipinos. Recognizing its role, the DOE reaffirms its commitment - to ensure quality, reliability, security, and affordabiliity of the supply of electric power. Through an integrated approach, the Power Development Plan 2016-2040 encompasses all subsectors - generation, transmission, distribution and supply; as well as the development of the market, other institutional support mechanisms and electrification roadmaps. POWER DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2016 - 2040 MESSAGE FROM THE SECRETARY he Department of Energy (DOE) is honored to present its Power TDevelopment Plan (PDP) 2016-2040. This blueprint will shape and redefine the future of the Philippine electric power industry. In line with the country’s long term national vision to be a middle- class society contained in the AmBisyon 2040, the PDP exemplifies the DOE’s aspiration to be a globally-competitive agency powering up Filipino communities through clean, efficient, robust and sustainable energy systems. The DOE aims to create wealth, propel industries and transform the lives of men and women and the future generations. The power demand and supply outlook discussed in the PDP will guide ALFONSO G. CUSI investors, economic planners and stakeholders of the power sector’s SECRETARY future landscape in terms of electricity consumption, demand and capacity requirements in the advent of an industrialization-driven economic growth and development. -

24Th Electric Power Industry Reform Act Implementation Status Report (Period Covering November 2013 to April 2014)

24th Electric Power Industry Reform Act Implementation Status Report (Period Covering November 2013 to April 2014) Prepared by the Department of Energy With Contributions from Energy Regulatory Commission Philippine Electricity Market Corporation National Power Corporation National Electrification Administration Power Sector Assets and Liabilities Management Corporation National Transmission Corporation 24th Status Report on EPIRA Implementation CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 II. PRIVATIZATION ............................................................................................................... 2 A. Privatization of Generating Assets .............................................................................. 2 B. Transfer of NPC Contracted Energy Outputs from its IPPs to Independent Administrators ................................................................................................................... 4 C. Privatization Proceeds ................................................................................................ 6 D. Concession of the National Transmission Network ..................................................... 6 E. Sale of Sub-Transmission Assets (STAs) ................................................................... 7 III. ELECTRICITY RATES ..................................................................................................... 8 A. Distribution Utilities’ Electricity Rates -

Rupture Process of the M7.2 October 2013 Bohol, Philippines Earthquake

Rupture Process of the M7.2 October 2013 Bohol, Philippines Earthquake Acknowledgement: Tomokazu Kobayashi Muriel Naguit1, Phil R. Cummins1,2 and Bart Bautista3 1Research School of Earth Sciences, Australian National University 2Geoscience Australia, Canberra, Australia 3Philippines Institute of Vulcanology and Seismology Outline • Development of a rupture model – M7.2 October 2013 Bohol earthquake – Joint inversion of multiple datasets (seismic waveforms & SAR radar image) • Post-damage assessment – Correlate observed ground motions with damage observations – Constrain & validate building fragility curves & vulnerability models 2 The 2013 M7.2 Bohol Earthquake • Event: October 15, 2013 at 8:12:31 AM local time • Casualties: 210 fatalities & 877 injuries • Structural damage: 71,885 totally & 57,405 partially damaged • Cost: up to US$53M, US$34M of which was infrastructure damage 3 NEIC Finite Fault Model SE dipping rupture plane consistent with geologic & SAR data. Most slip concentrated at asperity SW of hypocentre, and offshore Bohol. 4 Kobayashi et al. SAR Fault Model • Kobaysashi et al. (2014) used RADARSAT data to resolve coseismic displacement • Heavy vegetation precluded the use of conventional InSAR, so pixel tracking was used. • Inferred strike and dip are differ considerable w.r.t seismic estimates • Coseismic uplift appears distributed almost evenly along strike 5 Joint Seismic/SAR Fault Model 6 Use of Exsim to Model Ground Motions From USGS From EXSIM 7 Local Geology Metavolcanics or metamorphosed submarine flows Marine pyroclastics -

The Project for Study on Improvement of Bridges Through Disaster Mitigating Measures for Large Scale Earthquakes in the Republic of the Philippines

THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS (DPWH) THE PROJECT FOR STUDY ON IMPROVEMENT OF BRIDGES THROUGH DISASTER MITIGATING MEASURES FOR LARGE SCALE EARTHQUAKES IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES FINAL REPORT EXECTIVE SUMMARY DECEMBER 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD CHODAI CO., LTD. NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. EI JR(先) 13-261(1) Exchange Rate used in the Report is: PHP 1.00 = JPY 2.222 US$ 1.00 = JPY 97.229 = PHP 43.756 (Average Value in August 2013, Central Bank of the Philippines) LOCATION MAP OF STUDY BRIDGES (PACKAGE B : WITHIN METRO MANILA) i LOCATION MAP OF STUDY BRIDGES (PACKAGE C : OUTSIDE METRO MANILA) ii B01 Delpan Bridge B02 Jones Bridge B03 Mc Arthur Bridge B04 Quezon Bridge B05 Ayala Bridge B06 Nagtahan Bridge B07 Pandacan Bridge B08 Lambingan Bridge B09 Makati-Mandaluyong Bridge B10 Guadalupe Bridge Photos of Package B Bridges (1/2) iii B11 C-5 Bridge B12 Bambang Bridge B13-1 Vargas Bridge (1 & 2) B14 Rosario Bridge B15 Marcos Bridge B16 Marikina Bridge B17 San Jose Bridge Photos of Package B Bridges (2/2) iv C01 Badiwan Bridge C02 Buntun Bridge C03 Lucban Bridge C04 Magapit Bridge C05 Sicsican Bridge C06 Bamban Bridge C07 1st Mandaue-Mactan Bridge C08 Marcelo Fernan Bridge C09 Palanit Bridge C10 Jibatang Bridge Photos of Package C Bridges (1/2) v C11 Mawo Bridge C12 Biliran Bridge C13 San Juanico Bridge C14 Lilo-an Bridge C15 Wawa Bridge C16 2nd Magsaysay Bridge Photos of Package C Bridges (2/2) vi vii Perspective View of Lambingan Bridge (1/2) viii Perspective View of Lambingan Bridge (2/2) ix Perspective View of Guadalupe Bridge x Perspective View of Palanit Bridge xi Perspective View of Mawo Bridge (1/2) xii Perspective View of Mawo Bridge (2/2) xiii Perspective View of Wawa Bridge TABLE OF CONTENTS Location Map Photos Perspective View Table of Contents Abbreviations PART 1: GENERAL CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... -

2015 Oct FINAL BOHOL REPORT Orphan Churches OPTIMZED

PRELIMINARY EXISTING CONDITION SURVEY: THE ORPHAN CHURCHES OF BOHOL PREPARED BY: Bakás Pilipinas, Inc. FOR: The Diocese of Tagbilaran, Bohol OCTOBER 2015 FINAL PRELIMINARY EXISTING CONDITION SURVEY: THE ORPHAN CHURCHES OF BOHOL PREPARED BY: Bakás Pilipinas, Inc. P O Box 2706, Church Street Station New York, New York 10008 [email protected] www.bakaspilipinas.org FOR: The Diocese of Tagbilaran Tagbilaran City Bohol, Philippines OCTOBER 2015 FINAL Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................... 1 2. INTRODUCTION 2.1 Project Understanding and Approach..................................... 2 2.2 Survey Methodology ................................................. 2 2.3 Available Information ................................................ 3 2.4 Stipulation ......................................................... 3 2.5 Monitoring of Conditions ............................................. 3 3. BACKGROUND 3.1 Background ........................................................ 4 3.2 General Church History ............................................... 4 3.3 Statement of Significance ............................................. 5 4. GENERAL DESCRIPTION AND CONDITIONS 4.1 Soil and Foundation Conditions ......................................... 6 4.2 Construction Type ................................................... 6 4.3 Material Properties ................................................... 8 4.4 Geometry and Configuration ........................................... 9 4.5 Light Weight Roof Diaphragm ........................................ -

Yolanda & Other Recent Crises As of 2013 Nov 25

GK’s Response to Typhoon Yolanda & Other Recent Crises As of 2013 Nov 25 Background Super Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda) made landfall in the Philippines last Nov 8 and did no holding back in causing widespread grief and devastation. With strong winds and a storm surge that collapsed infrastructure, cut power and communication, exhausted supplies and took away thousands of lives, the government has declared the country under a state of national calamity. The public and private sectors, the Filipinos and the international community, are coming together to turn this calamity into one of the country’s biggest staging of Bayanihan, heroism and hope. Since its establishment in 2003, GK has been at the frontlines of disaster relief and rebuilding efforts. More importantly, however, GK has spent the past ten years building peaceful and productive communities – probably the most proactive and long-term solution to the “new normal” being felt across the globe. Our Immediate Response (1) Providing food and water for survival – Food and water are the most urgent needs for those who survived the storm. To date, GK has distributed ~100,000 food packs (~6 meals for a family of 5) in the Visayas region. Our target is to have distributed 200,000 food packs by first week of December. (2) Established strategic bases of operation – We have established 3 bases of operation: (a) Borongan, Eastern Samar (b) Baybay, Leyte, and (c) Tacloban, Leyte, serving as main hubs that receive and deploy help to the hardest-hit areas and nearby provinces. We have been bringing relief to Antique, North Negros, North Cebu, Aklan, Capiz & Iloilo; however, most of the food packs are being shipped from Manila command centers (DAR & FTI) due to supply challenges in the localities. -

The 2013 Bohol Earthquake in Central Philippines: Hazards and Source Fault Characteristics

The 2013 Bohol earthquake in central Philippines: Hazards and source fault characteristics Noelynna T. Ramos1, Kathrine V. Maxwell1, Betchaida D. Payot1, Nichole Anthony D. Pacle1, Carla B. Dimalanta1, Karlo L. Queaño2, Decibel V. Faustino-Eslava3 and Graciano P. Yumul, Jr.2,4 1National Institute of Geological Sciences, College of Science, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines 2Monte Oro Resources and Energy Inc., Makati City, Philippines 3School of Environmental Science and Management, University of the Philippines, Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines 4Apex Mining Company Inc., Ortigas City, Philippines 7th South China Sea Tsunami Workshop 21 November 2014 | National Museum of Natural Science, Taichung, Taiwan Outline Background Seismotectonic setting The 2013 Bohol earthquake Regional geology Geological hazards Surface rupture Shoreline deformation Karst collapses Implications for source fault Highlights and future work Ramos et al. | The 2013 Bohol Earthquake, Philippines SCSTW-7, Taichung, Taiwan 1 Seismotectonicsetting of the Philippines Data sources: NASA, NGDC, PHIVOLCS, Tsutsumi and Perez (2013) N.Ramos Ramos et al. | The 2013 Bohol Earthquake, Philippines SCSTW-7, Taichung, Taiwan Notable earthquakes in the Philippines *17 Aug 1976 Moro Gulf (MS8.0) *08 Feb 1990 Bohol (MS6.6) 16 Jul 1990 Luzon (MS7.7) *17 May 1992 eastern Mindanao (MS7.1~7.5) *15 Nov 1994 Mindoro (7.8) 06 Mar 2002 Sultan Kudarat (6.8) 15 Feb 2003 Masbate (6.2) 06 Feb 2012 Negros Oriental (mb6.9) 15 Oct 2013 Bohol (MW7.2) *tsunamigenic Ramos et al. | The 2013 Bohol Earthquake, Philippines SCSTW-7, Taichung, Taiwan 2 1990 Bohol tsunamigenic earthquake (Ms6.6) Besana et al., 2005 • Southeastern shorelines experienced a regional retreat (10 to 60 m) of sea water several minutes after the quake • Small to moderate tsunami waves (0.2 to 2 m) Ramos et al. -

Local Government-Volunteer Collaboration for Disaster Risk Management in the Philippines

Philippine Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 63, No. 2 (July-December 2019) Local Government-Volunteer Collaboration for Disaster Risk Management in the Philippines ERWIN A. ALAMPAY National College of Public Administration and Governance CHARLIE E. CABOTAJE National College of Public Administration and Governance LYDIA E. ANGELES National College of Public Administration and Governance MARIA LORIZA G. ODULIO National College of Public Administration and Governance DON JEFFERY A. QUEBRAL National College of Public Administration and Governance The implementing rules of the Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (DRRM) Act of 2010 make specific reference to volunteer participation. Hence, DRRM is an area where local government units (LGUs) need volunteers and have opportunities for volunteer engagement. This article provides examples of volunteering at the local level related to DRRM in the Philippines. It analyzes six cases of the Valuing Volunteering Project, which systematically presented local government and volunteer interactions by looking at how they are legally institutionalized, their systems and structure for coordination, spaces for volunteers to be involved, and their benefits. It interrogates the tension between cooperation, collaboration, and control that are inherent in the relationship between local governments and nongovernment organizations. With government policies that encourage, support, and provide spaces for civic engagement in local government, this exploration can contribute to improving the understanding of LGU-civil society organization engagements through volunteering. Keywords: climate change adaptation, collaborative governance, disaster risk reduction management, volunteerism “Most of the dead were asleep Friday night when raging floodwaters tore through their homes from swollen rivers and cascaded from mountain slopes following 12 hours of pounding rain in the southern Mindanao region. -

On 15 October 2013, a Very Destructive Earthquake 30

e **t On 15 October 2013, a very destructive earthquake (8:12 am local time) shook Bohol lsland and the entire Visayas Region, causing significant damage to houses, buifdings and infrastructures: lt had a rnagnitude of 7 "2, focal depth of 12 km and its epicenter was plotted near the boundary of the municipalities of Sagbayan and Catigbian in Bohol {6 km S24'W of Sagbayan; 7 km East of Catigbian and 34 km N45'E of Tagbilaran City). As of 30 November 2013, at least 3,900 aftershocks were recorded, of which more than 100 were reported felt. This earthquake was generated by the North Bohol Fault (NBF). Aerial view of the surface rupture of the North Eohol Fault (NBF) in Brgy, Anonang, Inabanga, Bohol The earthquake was associated with surface rupture and produced strong ground shaking, liquefaction and earthquake-ind uced landslides. Because of the ground shaking several sinkholes appeared after the earthquake. Severe damage to houses and infrastructures, including century-old heriiage churches, was observed. There were more than 200 deaths and 600,000 affected fami- lies. The estimated cost of damage to public infra- structures amounted to at least two billion Philip- 2.5-meter fault scarp in 8rgy, Anonang, Inabanga, Bohol pine pesos or 50 million US dollars. Collapsed frontage of a century-old church in Loay, Bohol The epicenter (red star) af the 1.5 October 2O13 Magnitude (Mw) 7.2 Bohol Earthquake and preliminary plottings of its aftershocks (yellow circles) (PHIVOLCS weblist Oct. 1.5 - Nov. 3, 2013). Colors show intensihes (in PEIS) sirnulated using the Rapid Earthquake Damage Assessmenf Software (REDAS) and f ault orientation f rom the initial PHIVOLCS-JICA]ST SWIFT focal mechanism. -

Dangerous Aspects of Reclamation Along Manila Bay and Laguna De

2/15/2016 Dangerous Aspects of Reclamation Along Manila Bay and Laguna de Bay NAST Policy Discussion on the Hazards, Risks and Profits of Reclamation Hotel Jen Manila, Roxas Blvd., Pasay City 15 February 2016 Kelvin S. Rodolfo, Professor Emeritus of Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago Senior Research Fellow, Manila Observatory Corresponding Member, National Academy of Science and Technology Four reasons why reclamation of nearshore Manila Bay and Laguna de Bay is a VERY BAD IDEA: 1. Rapid subsidence of coastal lands is enhancing the risk of flooding and high tides. 2. Storm surges are an ever-worsening threat, due in part to subsidence, but also because climate change is increasing the frequency of the strongest typhoons. 3. Reclaimed coastal areas are very susceptible to liquefaction and enhanced ground-shaking during earthquakes. 4. These risks are enhanced by DPWH’s and JICA’s ignoring or minimizing the phenomena in their projects. Our most susceptible area is the site of the Laguna Lake Expressway-Dike and proposed airport. 1 2/15/2016 Php 338.8 Billion 2 2/15/2016 Lutong Macao! It is taken for granted that both locations are feasible; the only question is which is best. In fact, both are very dangerous and unsuitable. This is a prime example of how JICA, DPWH, JBIC and other foreign lnders make suckers out of the Filipino taxpayers, and endanger them at the same time. I have a list of expensive and lethal examples. 3 2/15/2016 How the scam works 1. A private or public proponent (or both together) propose an expensive project. -

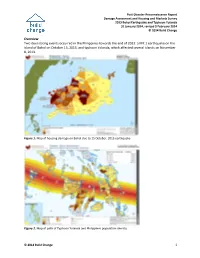

Philippines Reconnaissance Report

Post-Disaster Reconnaissance Report Damage Assessment and Housing and Markets Survey 2013 Bohol Earthquake and Typhoon Yolanda 31 January 2014, revised 5 February 2014 © 2014 Build Change Overview Two devastating events occurred in the Philippines towards the end of 2013: a M7.1 earthquake on the island of Bohol on October 15, 2013, and typhoon Yolanda, which affected several islands on November 8, 2013. Figure 1. Map of housing damage on Bohol due to 15 October, 2013 earthquake Figure 2. Map of path of Typhoon Yolanda and Philippines population density © 2014 Build Change 1 Post-Disaster Reconnaissance Report Damage Assessment and Housing and Markets Survey 2013 Bohol Earthquake and Typhoon Yolanda 31 January 2014, revised 5 February 2014 © 2014 Build Change The M7.1 Central Visayas earthquake hit near the city of Catigbian, Bohol Island in the Philippines on October 15, 2013. According to the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC), the earthquake killed 222 people and injured 976. 671,103 families, or 3,221,248 people, have been affected. Over 73,000 houses have been damaged, with 14,512 houses considered completely destroyed and 58,490 partially damaged. The International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC) reports in its 22 November, 2013 Emergency Appeal and Operation Update that some families have started to construct makeshift houses using salvaged material, though the majority of those with damaged houses remain in temporary shelters or are living with host families. An estimated 14.4 million people have been affected by Typhoon Yolanda, which hit several islands in the Philippines on November 8, 2013.