From Hnefatafl to Chess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old Norse Mythology — Comparative Perspectives Old Norse Mythology— Comparative Perspectives

Publications of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature No. 3 OLd NOrse MythOLOgy — COMParative PersPeCtives OLd NOrse MythOLOgy— COMParative PersPeCtives edited by Pernille hermann, stephen a. Mitchell, and Jens Peter schjødt with amber J. rose Published by THE MILMAN PARRY COLLECTION OF ORAL LITERATURE Harvard University Distributed by HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England 2017 Old Norse Mythology—Comparative Perspectives Published by The Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, Harvard University Distributed by Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England Copyright © 2017 The Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature All rights reserved The Ilex Foundation (ilexfoundation.org) and the Center for Hellenic Studies (chs.harvard.edu) provided generous fnancial and production support for the publication of this book. Editorial Team of the Milman Parry Collection Managing Editors: Stephen Mitchell and Gregory Nagy Executive Editors: Casey Dué and David Elmer Production Team of the Center for Hellenic Studies Production Manager for Publications: Jill Curry Robbins Web Producer: Noel Spencer Cover Design: Joni Godlove Production: Kristin Murphy Romano Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Hermann, Pernille, editor. Title: Old Norse mythology--comparative perspectives / edited by Pernille Hermann, Stephen A. Mitchell, Jens Peter Schjødt, with Amber J. Rose. Description: Cambridge, MA : Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, 2017. | Series: Publications of the Milman Parry collection of oral literature ; no. 3 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifers: LCCN 2017030125 | ISBN 9780674975699 (alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Mythology, Norse. | Scandinavia--Religion--History. Classifcation: LCC BL860 .O55 2017 | DDC 293/.13--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017030125 Table of Contents Series Foreword ................................................... -

The Lewis Chessmen on a Fantasy Iceland

THE LEWIS CHESSMEN ON A FANTASY ICELAND Morten Lilleøren, November 2011 In 2010, engineer Gudmundur Thorarinsson, helped in some undefined capacity by his public relations specialist Einar Einarsson, published the seldom-visited view that the Lewis pieces were made in Iceland. The revised version of this article, Are the Isle of Lewis Chessmen Icelandic?, as well as his subsequent publications on this topic, may be found at his website: http://leit.is/lewis/. Thorarinsson’s view was addressed in an article by Dylan Loeb McClain of the New York Times, in his somewhat cryptically entitled, Reopening History of Storied Norse Chessmen (http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/09/arts/09lewis.html). Their notion of an Icelandic origin for the Lewis pieces was given substantial promotion by Thorarinsson and Einarsson at those conferences and symposia they could attend. The idiosyncratic idea was not entirely ignored in academic and specialist circles as well. I entered this discussion because I was shocked at the poor method employed by Thorarinsson in the pursuit of support for his theory. Accordingly, I published a riposte to his initial article in May, 2011. I entitled this first essay of mine, The Lewis Chessmen were never anywhere near Iceland, and published it on Chess Café (http://www.chesscafe.com/text/skittles399.pdf). Thorarinsson then published a counter to my questions. Continuing to center his argument on a series of circumstantially-derived and –supported points, he went on to state that, “On behalf of Norway, I am thoroughly disappointed…[and moreover] I meant only to participate in literate discussions and studies” (op. -

ABSTRACT Savannah Dehart. BRACTEATES AS INDICATORS OF

ABSTRACT Savannah DeHart. BRACTEATES AS INDICATORS OF NORTHERN PAGAN RELIGIOSITY IN THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES. (Under the direction of Michael J. Enright) Department of History, May 2012. This thesis investigates the religiosity of some Germanic peoples of the Migration period (approximately AD 300-800) and seeks to overcome some difficulties in the related source material. The written sources which describe pagan elements of this period - such as Tacitus’ Germania, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and Paul the Deacon’s History of the Lombards - are problematic because they were composed by Roman or Christian authors whose primary goals were not to preserve the traditions of pagans. Literary sources of the High Middle Ages (approximately AD 1000-1400) - such as The Poetic Edda, Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda , and Icelandic Family Sagas - can only offer a clearer picture of Old Norse religiosity alone. The problem is that the beliefs described by these late sources cannot accurately reflect religious conditions of the Early Middle Ages. Too much time has elapsed and too many changes have occurred. If literary sources are unavailing, however, archaeology can offer a way out of the dilemma. Rightly interpreted, archaeological evidence can be used in conjunction with literary sources to demonstrate considerable continuity in precisely this area of religiosity. Some of the most relevant material objects (often overlooked by scholars) are bracteates. These coin-like amulets are stamped with designs that appear to reflect motifs from Old Norse myths, yet their find contexts, including the inhumation graves of women and hoards, demonstrate that they were used during the Migration period of half a millennium earlier. -

Hƒ›R's Blindness and the Pledging of Ó›Inn's

Hƒ›r’s Blindness and the Pledging of Ó›inn’s Eye: A Study of the Symbolic Value of the Eyes of Hƒ›r, Ó›inn and fiórr Annette Lassen The Arnamagnæan Institute, University of Copenhagen The idea of studying the symbolic value of eyes and blindness derives from my desire to reach an understanding of Hƒ›r’s mythological role. It goes without saying that in Old Norse literature a person’s physiognomy reveals his characteristics. It is, therefore, a priori not improbable that Hƒ›r’s blindness may reveal something about his mythological role. His blindness is, of course, not the only instance in the Eddas where eyes or blindness seem significant. The supreme god of the Old Norse pantheon, Ó›inn, is one-eyed, and fiórr is described as having particularly sharp eyes. Accordingly, I shall also devote attention in my paper to Ó›inn’s one-eyedness and fiórr’s sharp gaze. As far as I know, there exist a couple of studies of eyes in Old Norse literature by Riti Kroesen and Edith Marold. In their articles we find a great deal of useful examples of how eyes are used as a token of royalty and strength. Considering this symbolic value, it is clear that blindness cannot be, simply, a physical handicap. In the same way as emphasizing eyes connotes superiority 220 11th International Saga Conference 221 and strength, blindness may connote inferiority and weakness. When the eye symbolizes a person’s strength, blinding connotes the symbolic and literal removal of that strength. A medieval king suffering from a physical handicap could be a rex inutilis. -

The Bulletin the Bulletin

The Bulletin The Bulletin Summer 2019 [email protected] Vol 20, Issue 2 www.merrickjc.org Winter 2020 [email protected] Vol 21, Issue 4 www.merrickjc.org Page 1 A Chanukah Message Light the Night II: The Return of the Guinness Record I’ll never forget the night when over one thousand of us gathered, each with our own Menorah, ready for the MJC to establish the Guin- ness Record for Most Menorot Lit in the same place at the same time. It was a glorious evening- one which filled us with enormous pride. We left the MJC that night feeling that we had celebrated Chanukah in a way that people all across our country would notice. And they did! The story of our triumph that night was told and retold in the media. How exciting it was to relive that thrill this past Sunday when so many of us joined together on Zoom to light our Menorot. Yes- we set the record once again! This will be a record for the ages. May we be together in person next year, feeling the uplift that is experienced whenever we gather as a community. Throughout Chanukah we’ll each light the Menorah and doing so will connect ourselves and our families spiritually with the great miracles which occurred in the time of the Maccabees. Especially this year, the light of the Menorah inspires us with the memory that even in the darkest of times our people did not succumb to despair. When we see how the Chanukah lights up our homes we understand the enduring meaning of this holiday which has served as a reminder for over 2000 years the great se- cret of Jewish existence has been the faith of our people that the worst moments were but a prelude to a better tomorrow. -

In Merovingian and Viking Scandinavia

Halls, Gods, and Giants: The Enigma of Gullveig in Óðinn’s Hall Tommy Kuusela Stockholm University Introduction The purpose of this article is to discuss and interpret the enig- matic figure of Gullveig. I will also present a new analysis of the first war in the world according to how it is described in Old Norse mythic traditions, or more specifically, how it is referred to in Vǫluspá. This examination fits into the general approach of my doctoral dissertation, where I try to look at interactions between gods and giants from the perspective of a hall environment, with special attention to descriptions in the eddic poems.1 The first hall encounter, depending on how one looks at the sources, is described as taking place in a primordial instant of sacred time, and occurs in Óðinn’s hall, where the gods spears and burns a female figure by the name of Gullveig. She is usually interpreted as Freyja and the act is generally considered to initiate a battle between two groups of gods – the Æsir and the Vanir. I do not agree with this interpretation, and will in the following argue that Gullveig should be understood as a giantess, and that the cruelty inflicted upon her leads to warfare between the gods (an alliance of Æsir and Vanir) and the giants (those who oppose the gods’ world order). The source that speaks most clearly about this early cosmic age and provides the best description is Vǫluspá, a poem that is generally considered to have been composed around 900– 1000 AD.2 How to cite this book chapter: Kuusela, T. -

HAMLET's MILL.Pdf

Hamlet's Mill An essay on myth and the frame of time GIORGIO de SANTILLANA Professor of the History and Philosophy of Science M.l.T. and HERTHA von DECHEND apl. Professor fur Geschichte der Naturivissenschaften ]. W. Goethe-Universitat Frankfurt Preface ASthe senior, if least deserving, of the authors, I shall open the narrative. Over many years I have searched for the point where myth and science join. It was clear to me for a long time that the origins of science had their deep roots in a particular myth, that of invariance. The Greeks, as early as the 7th century B.C., spoke of the quest of their first sages as the Problem of the One and the Many, sometimes describing the wild fecundity of nature as the way in which the Many could be deduced from the One, sometimes seeing the Many as unsubstantial variations being played on the One. The oracular sayings of Heraclitus the Obscure do nothing but illustrate with shimmering paradoxes the illusory quality of "things" in flux as they were wrung from the central intuition of unity. Before him Anaximander had announced, also oracularly, that the cause of things being born and perishing is their mutual injustice to each other in the order of time, "as is meet," he said, for they are bound to atone forever for their mutual injustice. This was enough to make of Anaximander the acknowledged father of physical science, for the accent is on the real "Many." But it was true science after a fashion. Soon after, Pythagoras taught, no less oracularly, that "things are numbers." Thus mathematics was born. -

Hiking Scotland's

Hiking Scotland’s North Highlands & Isle of Lewis July 20-30, 2021 (11 days | 15 guests) with archaeologist Mary MacLeod Rivett Archaeology-focused tours for the curious to the connoisseur. Clachtoll Broch Handa Island Arnol Dun Carloway (5.5|645) (6|890) BORVE Great Bernera & Traigh Uige 3 Caithness Dunbeath(4.5|425) (6|870) Stornoway (5|~) 3 3 BRORA Glasgow Isle of Lewis Callanish Lairg Standing Stones Ullapool (4.5|~) (4.5|885) Ardvreck LOCHINVER Castle Inverness Little Assynt # Overnight stays Itinerary stops Scottish Flights Hikes (miles|feet) Highlands Ferry Archaeological Institute of America Lecturer & Host Dr. Mary MacLeod oin archaeologist Mary MacLeod Rivett and a small group of like- Rivett was born in minded travelers on this 11-day tour of Scotland’s remote north London, England, to J Highlands and the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. Mostly we a Scottish-Canadian family. Her father’s will explore off the well-beaten Highland tourist trail, and along the way family was from we will be treated to an abundance of archaeological and historical sites, Scotland’s Outer striking scenery – including high cliffs, sea lochs, sandy and rocky bays, Hebrides, and she mountains, and glens – and, of course, excellent hiking. spent a lot of time in the Hebrides as a child. Mary earned her Scotland’s long and varied history stretches back many thousands of B.A. from the University of Cambridge, years, and archaeological remains ranging from Neolithic cairns and and her M.A. from the University of stone circles to Iron Age brochs (ancient dry stone buildings unique to York. -

A Game of Love and Chess: a Study of Chess Players on Gothic Ivory Mirror Cases

A GAME OF LOVE AND CHESS: A STUDY OF CHESS PLAYERS ON GOTHIC IVORY MIRROR CASES A thesis submitted to the Kent State University Honors College In partial fulfillment of the requirements For University Honors By Caitlin Binkhorst May, 2013 Thesis written by Caitlin Binkhorst Approved by _____________________________________________________________________, Advisor _________________________________________________, Director, Department of Art Accepted by ___________________________________________________, Dean, Honors College ii iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS…………………………………………………………....... v LIST OF FIGURES…………………………………………………………………..... vi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………….. 1 II. ANALYSIS OF THE “CHESS PLAYER” MIRROR CASES………. 6 III. WHY SO SIMILAR? ........................................................................ 23 IV. CONECTIONS OF THE “CHESS PLAYER” MIRROR CASES TO CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE ...………………………………. 31 V. THE CONTENT OF THE PIECE: CHESS ………………………...... 44 VI. CONCLUSION……………………………………………………….. 55 FIGURES………………………………………………………………………………. 67 WORKS CITED……………………………………………………………………….. 99 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude for all those who have helped me through this project over the past two years. First, I would like to thank my wonderful advisor Dr. Diane Scillia, who has inspired me to think about this period of art in a whole new way, and think outside of what past researchers have put together. I would also like to thank the members of my committee Dr. Levinson, Sara Newman, and Dr. Gus Medicus, as well as my other art history professors at Kent State, Dr. Carol Salus, and Dr. Fred Smith who have all broadened my mind and each made me think about art in an entirely different way. Furthermore, I would like to thank my professors in crafts, Janice Lessman-Moss and Kathleen Browne who have always reminded me to think about how art is made, but also how art functions in daily life. -

History of Chess from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia for the Book by H

History of chess From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For the book by H. J. R. Murray, see A History of Chess. Real-size resin reproductions of the 12th century Lewis chessmen. The top row shows king, queen, and bishop. The bottom row shows knight, rook, and pawn. The history of chess spans some 1500 years. The earliest predecessor of the game probably originated in India, before the 6th century AD. From India, the game spread to Persia. When the Arabs conquered Persia, chess was taken up by the Muslim world and subsequently spread to Southern Europe. In Europe, chess evolved into roughly its current form in the 15th century. The "Romantic Era of Chess" was the predominant chess playing style down to the 1880s. It was characterized by swashbuckling attacks, clever combinations, brash piece sacrifices and dynamic games. Winning was secondary to winning with style. These games were focused more on artistic expression, rather than technical mastery or long-term planning. The Romantic era of play was followed by the Scientific, Hypermodern, and New Dynamism eras.[1] In the second half of the 19th century, modern chess tournament play began, and the first World Chess Championship was held in 1886. The 20th century saw great leaps forward in chess theory and the establishment of the World Chess Federation (FIDE). Developments in the 21st century include use ofcomputers for analysis, which originated in the 1970s with the first programmed chess games on the market. Online gaming appeared in the mid-1990s. Contents [hide] 1 Origin 2 India -

Chess & Bridge

2013 Catalogue Chess & Bridge Plus Backgammon Poker and other traditional games cbcat2013_p02_contents_Layout 1 02/11/2012 09:18 Page 1 Contents CONTENTS WAYS TO ORDER Chess Section Call our Order Line 3-9 Wooden Chess Sets 10-11 Wooden Chess Boards 020 7288 1305 or 12 Chess Boxes 13 Chess Tables 020 7486 7015 14-17 Wooden Chess Combinations 9.30am-6pm Monday - Saturday 18 Miscellaneous Sets 11am - 5pm Sundays 19 Decorative & Themed Chess Sets 20-21 Travel Sets 22 Giant Chess Sets Shop online 23-25 Chess Clocks www.chess.co.uk/shop 26-28 Plastic Chess Sets & Combinations or 29 Demonstration Chess Boards www.bridgeshop.com 30-31 Stationery, Medals & Trophies 32 Chess T-Shirts 33-37 Chess DVDs Post the order form to: 38-39 Chess Software: Playing Programs 40 Chess Software: ChessBase 12` Chess & Bridge 41-43 Chess Software: Fritz Media System 44 Baker Street 44-45 Chess Software: from Chess Assistant 46 Recommendations for Junior Players London, W1U 7RT 47 Subscribe to Chess Magazine 48-49 Order Form 50 Subscribe to BRIDGE Magazine REASONS TO SHOP ONLINE 51 Recommendations for Junior Players - New items added each and every week 52-55 Chess Computers - Many more items online 56-60 Bargain Chess Books 61-66 Chess Books - Larger and alternative images for most items - Full descriptions of each item Bridge Section - Exclusive website offers on selected items 68 Bridge Tables & Cloths 69-70 Bridge Equipment - Pay securely via Debit/Credit Card or PayPal 71-72 Bridge Software: Playing Programs 73 Bridge Software: Instructional 74-77 Decorative Playing Cards 78-83 Gift Ideas & Bridge DVDs 84-86 Bargain Bridge Books 87 Recommended Bridge Books 88-89 Bridge Books by Subject 90-91 Backgammon 92 Go 93 Poker 94 Other Games 95 Website Information 96 Retail shop information page 2 TO ORDER 020 7288 1305 or 020 7486 7015 cbcat2013_p03to5_woodsets_Layout 1 02/11/2012 09:53 Page 1 Wooden Chess Sets A LITTLE MORE INFORMATION ABOUT OUR CHESS SETS.. -

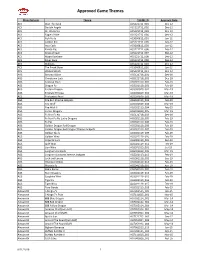

Approved Game Themes

Approved Game Themes Manufacturer Theme THEME ID Approval Date ACS Bust The Bank ACS121712_001 Dec-12 ACS Double Angels ACS121712_002 Dec-12 ACS Dr. Watts Up ACS121712_003 Dec-12 ACS Eagle's Pride ACS121712_004 Dec-12 ACS Fish Party ACS060812_001 Jun-12 ACS Golden Koi ACS121712_005 Dec-12 ACS Inca Cash ACS060812_003 Jun-12 ACS Karate Pig ACS121712_006 Dec-12 ACS Kings of Cash ACS121712_007 Dec-12 ACS Magic Rainbow ACS121712_008 Dec-12 ACS Silver Fang ACS121712_009 Dec-12 ACS Stallions ACS121712_010 Dec-12 ACS The Freak Show ACS060812_002 Jun-12 ACS Wicked Witch ACS121712_011 Dec-12 AGS Bonanza Blast AGS121718_001 Dec-18 AGS Chinatown Luck AGS121718_002 Dec-18 AGS Colossal Stars AGS021119_001 Feb-19 AGS Dragon Fa AGS021119_002 Feb-19 AGS Eastern Dragon AGS031819_001 Mar-19 AGS Emerald Princess AGS031819_002 Mar-19 AGS Enchanted Pearl AGS031819_003 Mar-19 AGS Fire Bull Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_003 Feb-19 AGS Fire Wolf AGS031819_004 Mar-19 AGS Fire Wolf II AGS021119_004 Feb-19 AGS Forest Dragons AGS031819_005 Mar-19 AGS Fu Nan Fu Nu AGS121718_003 Dec-18 AGS Fu Nan Fu Nu Lucky Dragons AGS021119_005 Feb-19 AGS Fu Pig AGS021119_006 Feb-19 AGS Golden Dragon Red Dragon AGS021119_008 Feb-19 AGS Golden Dragon Red Dragon Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_007 Feb-19 AGS Golden Skulls AGS021119_009 Feb-19 AGS Golden Wins AGS021119_010 Feb-19 AGS Imperial Luck AGS091119_001 Sep-19 AGS Jade Wins AGS021119_011 Feb-19 AGS Lion Wins AGS071019_001 Jul-19 AGS Longhorn Jackpots AGS031819_006 Mar-19 AGS Longhorn Jackpots Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_012 Feb-19 AGS Luck