The Diocese of Minsk, Its Origin, Extent and Hierarchy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

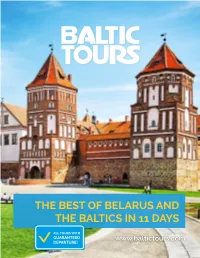

The Best of Belarus and the Baltics in 11 Days

THE BEST OF BELARUS AND THE BaLTICS IN 11 DAYS ALL TOURS WITH GUARANTEED www.baltictours.com DEPARTURE! 1 TRAVEL SPECIALISTS Vilnius, Lithuania SINCE 1991 Baltic Tours has been among the ranks of the best for 27 years! Since 2007 Baltic Tours in collaboration with well experienced tourism partners have guaranteed departure tour services offering for over 30 tour programs and more than 300 guaranteed departures per year. Our team believes in the beauty of traveling, in the vibe of adventure and the pleasure of gastronomy. Traveling is a pure happiness - it has become our way of living! I have a degree in tourism management and I encourage our guests to explore the Northeastern region of Europe in its most attractive way. I’ve been working in tourism industry since 2013 and I’m assisting customers from 64 countries. Take a look at my personally selected tours and grab your best deal now! SERVICE STANDARDS MORE VALUE GUARANTEED ESCORTED TOURS QUALITY, SAFETY AND SECURITY SPECIAL FEATURES PRE- AND POST- STAYS www.baltictours.com 3 Kadriorg Park, Tallinn, Estonia JUNE-August, 2021 INCLUDING 11 days/10 nights THE BEST OF TALLINN ● ESTONIA 10 overnight stays at centrally located 4* GBE11: 03 Jun - 13 Jun, 2021 BELARUS AND hotels GBE15: 01 Jul - 11 Jul, 2021 10 x buffet breakfast GBE19: 29 Jul - 08 Aug, 2021 RIGA LATVIA Welcome meeting with champagne-cocktail GBE21: 12 Aug - 22 Aug, 2021 or juice THE BALTICS Personalised welcome package LITHUANIA Entrances to Peter and Paul Church in Vilnius, Rundale Palace and medieval Great Guild IN 11 DAYS VILNIUS Hall in Tallinn MINSK Service of bilingual English-German speaking tour leader on all tours BELARUS Service of 1st class buses or 1st class minivans throughout the itinerary Train tickets Minsk-Vilnius, 2nd class, OW Portage at hotels -Charlotte- National Library of Belarus, Minsk, Belarus “First of all, I would like to say a lot of good words for Rasa. -

Passion for the Mission

Passion for the Mission Author: Javier Aguirregabiria Translated by: Father José Burgués Table of Contents I. PRESENTATION ........................................................................................................................... 1 1. A Proposal for the Beginning ............................................................................................ 1 FROM SILENCE .............................................................................................................................. 3 2. Logic of the Chapters ............................................................................................................. 3 For the Piarist and Those who Feel Piarist ............................................................................ 4 Mission as a Task ................................................................................................................... 4 II. WORK OF GOD AND OF CALASANZ ........................................................................................... 5 3. We Gratefully and Responsibly Accept this Gift ................................................................... 5 Poisoned Gift ......................................................................................................................... 6 Praying to God... .................................................................................................................... 6 4. It is You to Whom I am Calling ............................................................................................. -

The Baltic Republics

FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1994 Finnish Defence Studies is published under the auspices of the National Defence College, and the contributions reflect the fields of research and teaching of the College. Finnish Defence Studies will occasionally feature documentation on Finnish Security Policy. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily imply endorsement by the National Defence College. Editor: Kalevi Ruhala Editorial Assistant: Matti Hongisto Editorial Board: Chairman Prof. Mikko Viitasalo, National Defence College Dr. Pauli Järvenpää, Ministry of Defence Col. Antti Numminen, General Headquarters Dr., Lt.Col. (ret.) Pekka Visuri, Finnish Institute of International Affairs Dr. Matti Vuorio, Scientific Committee for National Defence Published by NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE P.O. Box 266 FIN - 00171 Helsinki FINLAND FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES 6 THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1992 ISBN 951-25-0709-9 ISSN 0788-5571 © Copyright 1994: National Defence College All rights reserved Painatuskeskus Oy Pasilan pikapaino Helsinki 1994 Preface Until the end of the First World War, the Baltic region was understood as a geographical area comprising the coastal strip of the Baltic Sea from the Gulf of Danzig to the Gulf of Finland. In the years between the two World Wars the concept became more political in nature: after Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania obtained their independence in 1918 the region gradually became understood as the geographical entity made up of these three republics. Although the Baltic region is geographically fairly homogeneous, each of the newly restored republics possesses unique geographical and strategic features. -

Patrocinium of Calasanz

The Patrocinium of St. Joseph Calasanz November 27 Although the Feast of St. Joseph Calasanz is celebrated on August 25, this date often falls at the end of summer vacation for most Piarist Schools. As a result, the religious order has designated November 27, which is the day he opened Europe’s first free public school, as the Patrocinium, a special day to honor and celebrate St. Joseph Calasanz. Joseph was born on September 11, 1557 in a tiny village called Peralta de la Sal. He was a Spanish priest from Aragon, Spain, who went to Rome at the end of the sixteenth century and started schools for poor and homeless children. He also started a religious congregation to serve these schools which is today spread throughout the world. He was well educated in philosophy, law and theology at the Spanish universities of Estadilla, Lerida, and Valencia. His family initially did not support his religious calling. His father wanted him to marry and to continue the family, but after recovering from an illness which brought him close to death, Calasanz was ordained as a priest on December 17, 1583. He subsequently became vicar general of Tremp. He later relinquished much of his inheritance and resigned his vicariate. For the next ten years, he held various posts as a secretary, administrator and theologian in the Diocese of Albarracín in Spain. In 1592, Joseph went to Rome, where he became a theologian in the service of Cardinal Marcoantonio Colonna and a tutor to his nephew. He worked alongside St. Camillus de Lellis during the plague, which hit Rome at the time. -

Brief of Appellee, Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Virginia

Record No. 120919 In the Supreme Court of Virginia The Falls Church (also known as The Church at the Falls – The Falls Church), Defendant-Appellant, v. The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America and The Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Virginia, Plaintiffs-Appellees. BRIEF OF APPELLEE PROTESTANT EPISCOPAL CHURCH IN THE DIOCESE OF VIRGINIA Bradfute W. Davenport, Jr. (VSB #12848) Mary C. Zinsner (VSB #31397) [email protected] [email protected] George A. Somerville (VSB #22419) Troutman Sanders LLP [email protected] 1660 International Drive, Suite 600 Troutman Sanders LLP McLean, Virginia 22102 P.O. Box 1122 (703) 734-4334 (telephone) Richmond, Virginia 23218-1122 (703 734-4340 (facsimile) (804) 697-1291 (telephone) (804) 697-1339 (facsimile) CONTENTS Table of Authorities .................................................................................... iiii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Facts ........................................................................................................... 2 Assignment of Cross-Error .......................................................................... 5 Argument .................................................................................................... 5 Standard of Review ........................................................................... 5 I. The Circuit Court correctly followed and applied this Court’s -

The Diocese of Minsk, Its Origin, Extent and Hierarchy

177 The Diocese of Minsk, its Origin, Extent and Hierarchy BY Č. SIPOVIČ I Those who would wish to study the history of Christianity in Byelorussia should certainly pursue the history of the Orthodox and Catholic churches, and to a lesser extent, that of various groups of Protestants. One must bear in mind that the Catholic Church in Byelorussia followed and still follows two Rites: the Latin and the Oriental-Byzantine. It is acceptable to call the latter by the name Uniate. In Byelorussia it dates back to the Synod of Brest-Litoŭsk in the year 1596. But here we propose to deal exclusively with the Catholic Church of the Latin Rite, and will further limit ourselves to a small section of its history, namely the foundation of the diocese of Minsk. Something also will be said of its bishops and admin istrators. Exactly how and when the Latin form of Catholicism came to Byelorussia is a question which has not been sufficiently elucidated. Here then are the basic historical facts. From the beginning of the acceptance of Christianity in Byelo russia until the end of the 14th century, the population followed the Eastern Rite and until the end of the 12th century it formed part of the universal Christian Church. After the erection of a Latin bishopric in Vilna in 1387, and after the acceptance of Christianity in the Latin Rite by the Lithuanians, this episcopal see itself and its clergy started to propagate this rite. It is well-known that Jahajła had virtually the same relations with the pagan Lithuanians as with Orthodox Ukrainians and Byelo russians. -

ZRBG – Ghetto-Liste (Stand: 01.08.2014) Sofern Eine Beschäftigung I

ZRBG – Ghetto-Liste (Stand: 01.08.2014) Sofern eine Beschäftigung i. S. d. ZRBG schon vor dem angegebenen Eröffnungszeitpunkt glaubhaft gemacht ist, kann für die folgenden Gebiete auf den Beginn der Ghettoisierung nach Verordnungslage abgestellt werden: - Generalgouvernement (ohne Galizien): 01.01.1940 - Galizien: 06.09.1941 - Bialystok: 02.08.1941 - Reichskommissariat Ostland (Weißrussland/Weißruthenien): 02.08.1941 - Reichskommissariat Ukraine (Wolhynien/Shitomir): 05.09.1941 Eine Vorlage an die Untergruppe ZRBG ist in diesen Fällen nicht erforderlich. Datum der Nr. Ort: Gebiet: Eröffnung: Liquidierung: Deportationen: Bemerkungen: Quelle: Ergänzung Abaujszanto, 5613 Ungarn, Encyclopedia of Jewish Life, Braham: Abaújszántó [Hun] 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Kassa, Auschwitz 27.04.2010 (5010) Operationszone I Enciklopédiája (Szántó) Reichskommissariat Aboltsy [Bel] Ostland (1941-1944), (Oboltsy [Rus], 5614 Generalbezirk 14.08.1941 04.06.1942 Encyclopedia of Jewish Life, 2001 24.03.2009 Oboltzi [Yid], Weißruthenien, heute Obolce [Pol]) Gebiet Vitebsk Abony [Hun] (Abon, Ungarn, 5443 Nagyabony, 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Encyclopedia of Jewish Life 2001 11.11.2009 Operationszone IV Szolnokabony) Ungarn, Szeged, 3500 Ada 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Braham: Enciklopédiája 09.11.2009 Operationszone IV Auschwitz Generalgouvernement, 3501 Adamow Distrikt Lublin (1939- 01.01.1940 20.12.1942 Kossoy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Life 09.11.2009 1944) Reichskommissariat Aizpute 3502 Ostland (1941-1944), 02.08.1941 27.10.1941 USHMM 02.2008 09.11.2009 (Hosenpoth) Generalbezirk -

Diocese of Sacramento Employment/Ministry in the Church Pre-Application Statement

Diocese of Sacramento Employment/Ministry in the Church Pre-Application Statement “Go out to the whole world and Proclaim the Good News to all creation.” (Mark 16:15) MISSION STATEMENT OF THE DIOCESE OF SACRAMENTO We, the People of God of the Catholic Diocese of Sacramento, guided by the Holy Spirit, are called by Christ to proclaim the Good News of the Kingdom of God through prayer, praise and sacraments and to witness the Gospel values of love, justice, forgiveness and service to all. All Christ’s faithful, by virtue of their baptism, are called by God to contribute to the sanctification and transformation of the world. They do this by fulfilling their own particular duties in the spirit of the Gospel and Christian discipleship. Working in the Church is a path of Christian discipleship to be encouraged. Those who work for the Church continue the mission and ministry of Christ. Their service is unique and necessary for the life and growth of the Church. This has been our tradition from the beginning, as echoed in the words of St. Paul who worked with and relied on other men and women in the work of spreading the Gospel. St. Paul was known to acknowledge and thank them, at times calling them, “my co-workers in Christ Jesus” (Romans 16:3- 16). The Church needs the services of dedicated lay persons who have a clear knowledge and proper understanding of the teachings of the Church and a firm adherence to those teachings, and whose words and deeds are in conformity with the Gospel. -

Religious Policy and Dissent in Socialist Hungary, 1974-1989. The

Religious Policy and Dissent in Socialist Hungary, 1974-1989. The Case of the Bokor-movement By András Jobbágy Submitted to Central European University History Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Nadia Al-Bagdadi Second Reader: Professor István Rév CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2014 Statement of Copyright Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library, Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection 1 Notes on translation All of my primary sources and much of the secondary literature I use are in Hungarian. All translations were done by me; I only give a few expressions of the original language in the main text. CEU eTD Collection 2 Abstract The thesis investigates religious policy, church-state relationships and dissent in late Kádárist Hungary. Firstly, by pointing out the interconnectedness between the ideology of the Catholic grass-root Bokor-movement and the established religious political context of the 1970s and 1980s, the thesis argues that the Bokor can be considered as a religiously expressed form of political dissent. Secondly, the thesis analyzes the perspective of the party-state regarding the Bokor- movement, and argues that the applied mechanisms of repression served the political cause of keeping the unity of the Catholic Church intact under the authority of the Hungarian episcopacy. -

Strategy 2020 of Euroregion „Country of Lakes”

THIRD STEP OF EUROREGION “COUNTRY OF LAKES” Strategy 2020 of Euroregion „Country of Lakes” Project „Third STEP for the strategy of Euroregion “Country of lakes” – planning future together for sustainable social and economic development of Latvian-Lithuanian- Belarussian border territories/3rd STEP” "3-rd step” 2014 Strategy 2020 of Euroregion „Country of Lakes” This action is funded by the European Union, by Latvia, Lithuania and Belarus Cross-border Cooperation Programme within the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument. The Latvia, Lithuania and Belarus Cross-border Cooperation Programme within the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument succeeds the Baltic Sea Region INTERREG IIIB Neighbourhood Programme Priority South IIIA Programme for the period of 2007-2013. The overall strategic goal of the programme is to enhance the cohesion of the Latvian, Lithuanian and Belarusian border region, to secure a high level of environmental protection and to provide for economic and social welfare as well as to promote intercultural dialogue and cultural diversity. Latgale region in Latvia, Panevėžys, Utena, Vilnius, Alytus and Kaunas counties in Lithuania, as well as Vitebsk, Mogilev, Minsk and Grodno oblasts take part in the Programme. The Joint Managing Authority of the programme is the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Lithuania. The web site of the programme is www.enpi-cbc.eu. The European Union is made up of 28 Member States who have decided to gradually link together their know-how, resources and destinies. Together, during a period of enlargement of 50 years, they have built a zone of stability, democracy and sustainable development whilst maintaining cultural diversity, tolerance and individual freedoms. -

The Holy See

The Holy See ORIENTALIS ECCLESIAE ENCYCLICAL OF POPE PIUS XII ON SAINT CYRIL, PATRIARCH OF ALEXANDRIA TO OUR VENERABLE BRETHREN THE PATRIARCHS, PRIMATES, ARCHBISHOPS, BISHIOPS, AND OTHER ORDINARIES AT PEACE AND IN COMMUNION WITH THE APOSTOLIC SEE Venerable Brethren, Health and Our Apostolic Benediction. St. Cyril, Patriarch of Alexandria, glory of the Eastern Church and celebrated champion of the Virgin Mother of God, has always been held by the Church in the highest esteem, and We welcome the opportunity of recalling his merits in this brief Letter, now that fifteen centuries have passed since he happily exchanged this earthly exile for his heavenly home. 2. Our Predecessor St. Celestine I hailed him as 'good defender of the Catholic faith,'[1] as 'excellent priest,'[2] as 'apostolic man.'[3] The ecumenical Council of Chalcedon not only used his doctrine for the detecting and refuting of the latest errors, but went so far as to compare it with the learning of St. Leo the Great;[4] and in fact the latter praised and commended the writings of this great Doctor because of their perfect agreement with the faith of the holy Fathers.[5] The fifth ecumenical Council, held at Constantinople, treated St. Cyril's authority with similar reverence[6] and many years later, during the controversy about the two wills in Christ, his teaching was rightly and triumphantly vindicated, both in the first Lateran Council [7] and in the sixth ecumenical Council, against the false charge of being tainted with the error of Monothelitism. He was, as Our saintly Predecessor Agatho proclaimed, 'a defender of the truth'[8] and 'a consistent teacher of the orthodox faith.'[9] 3. -

Keeping Gunpowder Dry Minsk Hosts the Council of Defence Ministers of the Commonwealth of Independent States

FOCUS The Minsk Times Thursday, June 13, 2013 3 Keeping gunpowder dry Minsk hosts the Council of Defence Ministers of the Commonwealth of Independent States By Dmitry Vasiliev Minsk is becoming ever more a centre for substantive discussions on integration. Following close on the heels of the Council of CIS Heads of Government and the Forum of Busi- nessmen, Minsk has hosted the CIS Council of Defence Ministers. The President met the heads of delegations before the Council began its work, noting, “We pay special im- portance to each event which helps strengthen the authority of our integra- tion association and further develop co-operation among state-partici- pants in all spheres.” Issues of defence and national security are, naturally, of great importance. The President added, “Bearing in mind today’s dif- ficult geopolitical situation worldwide, this area of integration is of particular importance for state stability and the sustainable development of the Com- monwealth.” Belarus supports the further all- round development of the Common- BELTA Prospective issues of co-operation discussed in Minsk at meeting of Council of CIS Defence Ministers wealth, strengthening its defence capa- bility and authority: a position shared any independence... We, Belarusians mark event in the development of close the military sphere is a component of sites in Russia and Kazakhstan and an by many heads of state considering and Russians, don’t have any secrets partnerships in the military sphere. integration, with priorities defined by international competition for the pro- integration. The President emphasised, from each other. If we don’t manage to Last year, the CIS Council of De- the concerns of friendly countries re- fessional military is planned: Warriors “Whether we like it or not, life forces achieve anything (Russia also has prob- fence Ministers — a high level inter- garding sudden complications in the of the Commonwealth.