TITLE: Isolation and Identification of Host-Plant Attractants for Cranberry Weevil and Cranberry Fruitworm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multi-Species Mating Disruption in Cranberries (Ericales: Ericaceae): Early Evidence Using a Flowable Emulsion

Journal of Insect Science (2017) 17(2): 54; 1–6 doi: 10.1093/jisesa/iex025 Research article Multi-Species Mating Disruption in Cranberries (Ericales: Ericaceae): Early Evidence Using a Flowable Emulsion Shawn A. Steffan,1,2,3 Elissa M. Chasen,1,2 Annie E. Deutsch,2,4 and Agenor Mafra-Neto5 1USDA-ARS Vegetable Crops Research Unit, 1630 Linden Drive, Madison, WI 53706 ([email protected]; elissa.chasen@ ars.usda.gov), 2Department of Entomology, University of Wisconsin, 1630 Linden Drive, Madison, WI 53706 (steffan@entomology. wisc.edu; [email protected]; [email protected]), 3Corresponding author, e-mail: ([email protected]), 4Door County University of Wisconsin-Extension, 421 Nebraska St., Sturgeon Bay, WI 54235 ([email protected]), and 5ISCA Technologies, Incorporated, 1230 W. Spring St., Riverside, CA 92507 ([email protected]) Subject Editor: Cesar Rodriguez-Saona Received 11 October 2016; Editorial decision 11 March 2017 Abstract Pheromone-based mating disruption has proven to be a powerful pest management tactic in many cropping systems. However, in the cranberry system, a viable mating disruption program does not yet exist. There are commercially available pheromones for several of the major pests of cranberries, including the cranberry fruit- worm, Acrobasis vaccinii Riley (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) and blackheaded fireworm, Rhopobota naevana (Hu¨ bner) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). Previous studies have shown that mating disruption represents a promising approach for R. naevana management although carrier and delivery technologies have remained unresolved. The present study examined the suitability of Specialized Pheromone & Lure Application Technology (SPLAT; ISCA Technologies, Inc., Riverside, CA), a proprietary wax and oil blend, to serve as a pheromone carrier in the cranberry system. -

Highbush Blueberry: Cultivation, Protection, Breeding and Biotechnology

The European Journal of Plant Science and Biotechnology ©2007 Global Science Books Highbush Blueberry: Cultivation, Protection, Breeding and Biotechnology Daniele Prodorutti1* • Ilaria Pertot2 • Lara Giongo3 • Cesare Gessler2 1 Plant Protection Department, IASMA Research Centre, Via E. Mach 1, 38010 San Michele all’Adige (TN), Italy 2 Safecrop Centre, IASMA Research Centre, Via E. Mach 1, 38010 San Michele all’Adige (TN), Italy 3 Agrifood Quality Department, IASMA Research Centre, Via E. Mach 1, 38010 San Michele all’Adige (TN), Italy Corresponding author : * [email protected] ABSTRACT Highbush blueberry is one of the most commercially significant berry crops. It is mainly cultivated in the United States and Canada, but also in Europe, Australia, Chile and New Zealand. Production of this crop is likely to increase in response to increased consumer demand for healthy foods, including the antioxidant-rich blueberry. This review describes several issues and developments in sustainable blueberry farming, including agronomical and cultural techniques (mulching, irrigation, the beneficial effects of mycorrhizae and fertilization), disease management (biology and control of common and emerging diseases), pest management, pollinators (effects on fruit set and production), conventional breeding and molecular techniques for examining and engineering blueberry germplasm. This paper describes past problems and current challenges associated with the commercial production of highbush blueberry, as well as new approaches and techniques for -

Series I. Correspondence, 1871-1894 Box 1 Folder 1 Darwin to Riley

Special Collections at the National Agricultural Library: Charles Valentine Riley Collection Series I. Correspondence, 1871-1894 Box 1 Folder 1 Darwin to Riley. June 1, 1871. Letter from Charles Darwin to Riley thanking him for report and instructions on noxious insects. Downs, Beckerham, Kent (England). (handwritten copy of original). Box 1 Folder 2 Koble to Riley. June 30, 1874. Letter from John C. Koble giving physical description of chinch bugs and explaining how the bugs are destroying corn crops in western Kentucky. John C. Koble of L. S. Trimble and Co., Bankers. Box 1 Folder 3 Saunders to Riley. Nov. 12, 1874. William Saunders receipt to C. V. Riley for a copy of descriptions of two insects that baffle the vegetable carnivora. William Saunders, Department of Agriculture, Washington, D. C. Box 1 Folder 4 Young to Riley. Dec. 13, 1874. William Young describes the flat-headed borer and its effects on orchards during summer and winter seasons. From Palmyra Gate Co., Nebraska. Box 1 Folder 5 Saunders to Riley. Dec. 22, 1874. William Saunders receipt of notes of investigation on the insects associated with Sarracenia. William Saunders, Department of Agriculture, Washington, D.C. Box 1 Folder 6 Bonhaw to Riley. Jan. 19, 1875. L. N. Bonhaw requesting a copy of his Missouri report, for him to establish a manual or handbook on entomology, and to find out about an insect that deposits eggs. Subject: tomato worm, hawk moth. 1 http://www.nal.usda.gov/speccoll/ Special Collections at the National Agricultural Library: Charles Valentine Riley Collection Box 1 Folder 7 Holliday to Riley. -

Lepidoptera: Pyralidae)

DAVID MARCHAND STRATÉGIES DE PONTE ET D’ALIMENTATION LARVAIRE CHEZ LA PYRALE DE LA CANNEBERGE, ACROBASIS VACCINII (LEPIDOPTERA: PYRALIDAE) Thèse présentée à la Faculté des études supérieures de l'Université Laval pour l’obtention du grade de Philosophiae Doctor (Ph. D.) Département de biologie FACULTÉ DES SCIENCES ET GÉNIE UNIVERSITÉ LAVAL QUÉBEC MAI 2003 © David Marchand, 2003 ii Résumé Chez les espèces d’insectes dont le développement larvaire nécessite plusieurs hôtes, la survie larvaire peut être dépendante à la fois du comportement d’oviposition des femelles et du comportement de recherche des larves. La présente thèse porte sur l'étude de ces deux comportements et leurs possibles impacts sur la performance larvaire de la pyrale de la canneberge, Acrobasis vaccinii (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae), une espèce dont chaque larve a besoin de plusieurs fruits de canneberge, Vaccinium oxycoccos (Ericacae), pour compléter son développement. Dans un premier temps, j’ai démontré que les femelles en laboratoire pondent significativement plus souvent sur les plus gros fruits disponibles; la taille des larves sortant du premier fruit choisi par la femelle étant proportionnelle à la taille de ce fruit. Cependant, sur le terrain, cette préférence n’a pas été observée et mon étude met en évidence que la période d’oviposition survient tôt dans la saison, dès l’apparition des premiers fruits; ceci impliquant une faible variabilité dans la taille des sites de ponte disponibles. Cette étude démontre également une distribution hétérogène des fruits de canneberge en nature et une variabilité importante dans la production annuelle de fruits entre mes deux années d’étude. Le fait que les fruits puissent être rares certaines années serait une raison conduisant les femelles à accepter les fruits de plus faible qualité (fruits de petite taille). -

Taxonomy of Acrobasis Larvae and Pupae in Eastern North America (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae)

" ; ! ,I ! l ~WW ~WW 1.0 ~ 1.0 ~ L W W 122 "' r I:.l . I:.lwWW. Ii.: ~ ~ Ii.: ~ : W 2.0 : w "'" .......... "" ..........• 112===== i ' ! 11111 1.1 f ~ 1.8 ! 111111.8 '1I111~ '"" 1.4 ~1l11.6 1111,1.25 111111.4 111111.6 MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS-J963-A NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS-J963-A , . ,,",.,_. ,. Taxonomy of Acrobasis Larvae and Pupae in Eastern North America (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) . .. Teclmical Bulletin No. 1457 ''":<! c... ~.jJ .r. ., -,,", 1= ") 0J r--c':' .,~ ,~ • . ~ r- ,.! .,..( ; CO? I ;:"'l C':! J. ;:. ") co ,;;. 1.0 (. ; '.'1 ~. L1 r· •.::1 ... i~ .' ! i. Agricultural Research Service UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE ;,. in cooperation with North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station '" Taxonomy of Acrobasis Larvae and Pupae in Eastern North America (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) i By H. H. Neunzig Technical Bulletin No. 1457 Agricultural Research Service UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE in cooperation with Nortl' Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station Washington, D.C. Issued December 1972 For sllle by the Suprrintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $1.25 Stock Number 0100-2471 Acknowledgments This shuy was conducted under Agricultural Research Service Grant No. 12-14-100-9150(33). -\ • E. L. Todd and D. M. Weisman of the Systematic Entomology Laboratory, Agricultural Research Service, made available for study the collection of AC1·obasi.s adults and immatures at the t U.S. National Museum of Natural History. Additional Acrobasis larvae and pupae from Florida and Wisconsin were provided by • D. H. Habeck of the University of Florida. -

Blueberry Vaccinium Tissue Culture

Risk Management Proposal: Revision of the level of post entry quarantine (PEQ) for blueberry (Vaccinium spp. excluding V. macrocarpon) imported as tissue culture from non-accredited facilities under the Import Health Standard (IHS) 155.02.06: Importation of Nursery Stock 14 August 2017 Plant Imports Plants, Food & Environment Ministry for Primary Industries Pastoral House 25 The Terrace PO Box 2526 Wellington 6140 New Zealand Tel: +64 4 894 0100 Fax: +64 4 894 0662 Email: [email protected] Disclaimer This document does not constitute, and should not be regarded as, legal advice. While every effort has been made to ensure the information in this document is accurate, the Ministry for Primary Industries does not accept any responsibility or liability whatsoever for any error of fact, omission, interpretation or opinion that may be present, however it may have occurred. Requests for further copies should be directed to: Plant Imports Plants, Food & Environment Ministry for Primary Industries PO Box 2526 Wellington 6140 New Zealand Email: [email protected] © Crown Copyright – Ministry for Primary Industries. Page 3 of 53 Submissions The Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) propose to amend the Vaccinium schedule of the import health standard 155.02.06: Importation of Nursery Stock (the IHS) to allow Vaccinium tissue cultures imported under option 3.2 of the IHS to undergo post entry quarantine (PEQ) in a lower level of physical and operational containment than is currently required. The proposed amendment is supported by this Risk Management Proposal (RMP). The purpose of an IHS is defined as follows in section 22(1) of the Biosecurity Act 1993 (the Act): “An import health standard specifies requirements that must be met to effectively manage risks associated with importing risk goods, including risks arising because importing the goods involves or might involve an incidentally imported new organism”. -

Insect Pests of Wild Cranberry, Vaccinium Macrocarpon, In

Document généré le 27 sept. 2021 22:22 Phytoprotection Insect pests of wild cranberry, Vaccinium macrocarpon, in Newfoundland and Labrador Les insectes de la canneberge sauvage, Vaccinium macrocarpon, à Terre-Neuve et Labrador P.L. Dixon et N.K. Hillier Volume 83, numéro 3, 2002 Résumé de l'article La canneberge (Vaccinium macrocarpon) a été développée commercialement à URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/706237ar Terre-Neuve à la fin des années '90. À ce moment là, les populations d'insectes DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/706237ar indigènes dans les cannebergières sauvages étaient peu connues, même si ces lieux pouvaient servir de réservoir aux ravageurs, entraînant un déplacement Aller au sommaire du numéro de ces derniers vers les sites commerciaux. Pour aider les producteurs à faire face aux ravageurs, la présence et la distribution de ces insectes ont été évaluées dans les cannebergières sauvages. Des adultes de la pyrale des atocas, Éditeur(s) Acrobasis vaccinii ont été capturés dans des pièges à phéromone alors que des larves ont été trouvées dans les fruits. La pyrale des atocas est un ravageur Société de protection des plantes du Québec (SPPQ)l commun et répandu. Des adultes de l'anneleur de la canneberge, Chrysoteuchia topiaria ont été capturés dans les pièges à phéromone mais aucune larve n'a ISSN été retrouvée dans les plants ni dans les échantillons de sol. Il n'y a pas d'évidence de la présence de la tordeuse des canneberges, Rhopobota naevana, 0031-9511 (imprimé) du charançon des atocas, Anthonomus musculus, de l'altise à tête rouge, Systena 1710-1603 (numérique) frontalis, ou de la cécidomyie des atocas, Dasineura oxycoccana, lesquels sont retrouvés ailleurs. -

Operational Guidelines for the Export of Fresh Us Blueberry

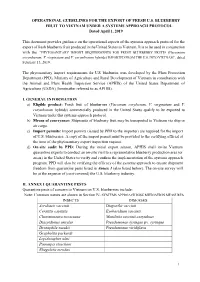

OPERATIONAL GUIDELINES FOR THE EXPORT OF FRESH U.S. BLUEBERRY FRUIT TO VIETNAM UNDER A SYSTEMS APPROACH PROTOCOL Dated April 1, 2019 This document provides guidance on the operational aspects of the systems approach protocol for the export of fresh blueberry fruit produced in the United States to Vietnam. It is to be used in conjunction with the “PHYTOSANITARY IMPORT REQUIREMENTS FOR FRESH BLUEBERRY FRUITS (Vaccinium corymbosum, V. virginatum and V. corymbosum hybrids) IMPORTED FROM THE U.S. INTO VIETNAM”, dated February 13, 2019. The phytosanitary import requirements for U.S. blueberries were developed by the Plant Protection Department (PPD), Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of Vietnam in consultation with the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (hereinafter referred to as APHIS). I. GENERAL INFORMATION a) Eligible product: Fresh fruit of blueberries (Vaccinum corybosum, V. virginatum and V. corymbosum hybrids) commercially produced in the United States qualify to be exported to Vietnam under this systems approach protocol. b) Means of conveyance: Shipments of blueberry fruit may be transported to Vietnam via ship or air cargo. c) Import permits: Import permits (issued by PPD to the importer) are required for the import of U.S. blueberries. A copy of the import permit must be provided to the certifying official at the time of the phytosanitary export inspection request. d) On-site audit by PPD: During the initial export season, APHIS shall invite Vietnam quarantine experts to conduct an on-site visit to a representative blueberry production area (or areas) in the United States to verify and confirm the implementation of the systems approach program. -

Cranberry Fruitworm in B.C. Tracy Hueppelsheuser British Columbia Ministry of Agriculture BC Cranberry Congress, Feb

Cranberry Fruitworm in B.C. Tracy Hueppelsheuser British Columbia Ministry of Agriculture BC Cranberry Congress, Feb. 11, 2015 1 Acknowledgements This project was funded in part by the BC Ministry of Agriculture and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada through Growing Forward 2, a federal-provincial- territorial initiative. Additional support was provided by: Cranberry and Blueberry Grower Cooperators B.C. Blueberry Council B.C. Cranberry Marketing Commission B.C. Cranberry Growers Association E.S. Cropconsult Ltd. Ocean Spray Cranberries Cranberry Fruitworm (Acrobasis vaccinii, Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) • Internal fruit feeding caterpillar, native to North America. • Infests blueberry and cranberry in eastern North America. • Moths detected for the first time in pheromone traps in a few BC cranberry fields in 2011. 3 Pest Biology: • Major Hosts: cranberry, blueberry. • Wild and minor crop hosts recorded: – Wild vaccinium – One generation per year. Pupae 4 life stages: Moth Larvae Eggs 4 Life cycle: • Moth emerges in summer (June-July) and lays eggs on green fruit (July). • Larvae hatch and burrow into developing fruit (July-Aug). • Larvae will infest 3-6 fruit before exiting and searching for an overwintering site (August). • Over-winters as larvae/pre-pupae in a silken structure in soil. • Pupates in spring/early summer. 5 Cranberry Fruitworm Moth Grey-brown moth with white triangles on wings; hind triangles with two dots each. Medium size moths, 15 mm wingspan. Note: there are moths that look similar; these tend to occur later, i.e. in August. Sometimes girdler moths will get into fruitworm traps. 6 Cranberry Fruitworm Eggs • Very small (1mm). Cannot identify without a lens. -

Appendix 1—Reviewers and Contributers

Appendix 1—Reviewers and Contributers The following individuals provided assistance, information, and review of this report. It could not have been completed without their cooperation. USDA APHIS-PPQ: D. Alontaga*, T. Culliney*, H. Meissner*, L. Newton* Hawai’i Department of Agriculture, Plant Industry Division: B. Kumashiro, C. Okada, N. Reimer University of Hawai’i: F. Brooks*, H. Spafford* USDA Forest Service: K. Britton*, S. Frankel* USDI Fish and Wildlife Service: D. Cravahlo Forest Research Institute Malaysia: S. Lee* 1 U.S. Department of the Interior, Geological Survey: L. Loope* Hawai’i Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Forestry and Wildlife: R. Hauff New Zealand Ministry for Primary Industries: S. Clark* Hawai’i Coordinating Group on Alien Pest Species: C. Martin* *Provided review comments on the draft report. 2 Appendix 2—Scientific Authorities for Chapters 1, 2, 3, and 5 Hypothenemus obscurus (F.) Kallitaxila granulatae (Stål) Insects Klambothrips myopori Mound & Morris Charaxes khasianus Butler Monema flavescens Walker Acizzia uncatoides (Ferris & Klyver) Neopithecops zalmora Butler Actias luna L. Nesopedronia dura Beardsley Adoretus sinicus (Burmeister) Nesopedronia hawaiiensis Beardsley Callosamia promethea Drury Odontata dorsalis (Thunberg) Ceresium unicolor White Plagithmysus bilineatus Sharp Chlorophorus annularis (F.) Quadrastichus erythrinae Kim Citheronia regalis Fabricus Scotorythra paludicola Butler Clastoptera xanthocephala Germ. Sophonia rufofascia Kuoh & Kuoh Cnephasia jactatana Walker Specularis -

Taxonomy of Acrobasis Larvae and Pupae in Eastern North America (Lepîdoptera: Pyralidae)

4 We. «^'«*^ 3 Taxonomy of Acrobasis Larvae and Pupae in Eastern North America (Lepîdoptera: Pyralidae) Technical Bulletin No. 1457 Agricultural Research Service UNITED STAT^JS DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE in cooperation with North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station /, ' Taxonomy of Acrohasis Larvae and Pupae in Eastern North America (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) By H. H. Neunzig Technical Bulletin No. 1457 Agricultural Research Service UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE in cooperation with North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station Washington, D.C. Issued December 1972 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $1.25 Stock Number 0100-2471 Acknowledgments This study was conducted under Agricultural Research Service Grant No. 12-14-100-9150(33). E. L. Todd and D. M. Weisman of the Systematic Entomology Laboratory, Agricultural Research Service, made available for study the collection of Acrobasis adults and immatures at the U.S. National Museum of Natural History. Additional Acrobasis larvae and pupae from Florida and Wisconsin were provided by D. H. Habeck of the University of Florida. I am grateful for the assistance of Betty W. Robbins of North Carolina State University. She reared, preserved, and measured immatures, mounted most of the associated adults, made genitalic dissections, and aided in numerous other ways in the study. A. L. Kyles, E. J. Venuto, T. R. Weaver, and J. D. Wellborn, all cf North Carolina State University, assisted in collecting and rearing. The parasites associated with Acrobasis larvae and pupae that were collected during the study were identified by the following specialists of the Systematic Entomology Laboratory : B. -

USDA Vaccinium Crop Vulnerability Statement FY 2018 Part 2: Cranberries Small Fruit Crop Germplasm Committee

USDA Vaccinium Crop Vulnerability Statement FY 2018 Part 2: Cranberries Small Fruit Crop Germplasm Committee Kim Hummer, Small Fruit Curator USDA Corvallis, Oregon Kim Lewers, Chair Small Fruit Crop Germplasm Committee, Beltsville, Maryland Nahla Bassil, Geneticist, USDA Corvallis, Oregon Nick Vorsa, Geneticist, Rutgers University, Chatsworth New Jersey Juan Zalapa, Geneticist USDA Madison, Wisconsin Massimo Iorizzo, Geneticist, North Carolina State University, Raleigh Karen Williams, Botanist, USDA Beltsville, Maryland Ioannis Tzanetakis, Plant Virologist, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville The large cranberry, Vaccinium macrocarpon Aiton, flowers (Wisconsin) and fruit being harvested. 1 The little leaf cranberry Vaccinium oxycoccos L. flowers and habitat in Hokkaido, Japan. Executive Summary Cranberries, Vaccinium macrocarpon Aiton, are native to North America. The U.S. is the world’s largest producer with Canada and Chile also producing significant quantities. The top producing states are Wisconsin, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Washington, Oregon, and Maine. In 2016, production was 683.725 tons. The economic value of fresh and processed cranberry production in the U.S. is $3.55 billion annually and represents > 11,600 jobs. In Canada, the value is $411 million and includes > 2,700 jobs. The desired fruit trait attributes of cranberry varieties has progressed over the last 100 years as the end products have changed. Initially high pectin content was a premium attribute for cranberry for sauce, followed by high anthocyanin content for juice drinks. Currently the main product is sweetend-dried-cranberry (SDC) for trail snacks. The fruit attributes for SDCs include homogeneous berry color, an anthocyanin color window, large fruit size (>2g/berry), and higher fruit firmness. A broad genepool for genetic improvement exists at the national cranberry genebank which is located at the U.S.