Transgender People and Human Rights Issues in Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iran and Central Asia: a Cultural Perspective1

Iran and Central Asia: A Cultural Perspective1 Davood Kiani One of the most important tools utilized by states to maximize their impact in foreign affairs is public diplomacy and to this extent, public diplomacy is considered a source of soft power. The robust use of public diplomacy can enhance and reinforce the soft power of countries. Central Asia is among the regions that have an ever increasing relevance to regional and international affairs in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union, and is currently considered a critical subsystem for our country. The foreign policy of the Islamic Republic of Iran towards this region is, on one hand, built on the foundation of converging factors in political, economic, and cultural arenas and looking towards opportunities for influence and cooperation. On the other hand, considering the divergent components, it also faces challenges and threats, the sum of which continues to effect the orientation of Iranian foreign policy towards the region. This article will study Iranian public diplomacy in this region and examine the opportunities and challenges, as well as, provide and proper model for a successful public diplomacy in the region of Central Asia, while taking into account the Islamic Republic of Iran’s tools and potential. Keywords: Public diplomacy, foreign affairs, Central Asia, Islamic Republic of Iran 1 This article is based on “Cultural Policies of the Islamic Republic of Iran in Central Asia” a research funded by Islamic Azad University, Qum Branch Assistant Professor, Islamic Azad University of Qom ([email protected]) (Received: 20 January 2014 Accepted: 5 June 2014) Iranian Review of Foreign Affairs, Vol. -

Champions for Learning

Champions for Learning The Legacy of the Learning Metrics Task Force November 2016 Editors: Kate Anderson and Tyler Ditmore Table of Contents Contributors: Asmah Ahmad, Tamar Atinc, Mame Ibra Bâ, Jean-Marc Bernard, Julia Gillard, Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................................ii Seamus Hegarty, Charles Kado, Annie Kidder, The road to 2015 ...........................................................................................................................................1 Lucy Lake, Mohammad Matar, LMTF 1.0 .....................................................................................................................................................4 Mercedes Miguel, Silvia Montoya, LMTF 2.0 .....................................................................................................................................................7 Dzingai Mutumbuka, Jordan Naidoo, Five key goals in LMTF 2.0 ......................................................................................................................7 Abbie Raikes, Saba Saeed, Syed Kamal Ud Din Shah, Katie Smith, and Rebecca Winthrop LMTF 2.0 outcomes ..................................................................................................................................8 The Learning Champions initiative ......................................................................................................10 Cover Photo: A Tanzanian teacher works with -

Need of Third Gender Justice in Indian Society

IJRESS Volume 2, Issue 12 (December 2012) ISSN: 2249-7382 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND AND LEGAL STATUS OF THIRD GENDER IN INDIAN SOCIETY Preeti Sharma* ABSTRACT The terms third gender and third sex describe individuals who are categorized as neither man or woman as well as the social category present in those societies who recognize three or more genders. To different cultures or individuals, a third gender or six may represent an intermediate state between men and women, a state of being both. The term has been used to describe hizras of India, Bangladesh and Pakistan who have gained legal identity, Fa'afafine of Polynesia, and Sworn virgins of the Balkans, among others, and is also used by many of such groups and individuals to describe themselves like the hizra, the third gender is in many cultures made up of biological males who takes on a feminine gender or sexual role. Disowned by their families in their childhood and ridiculed and abused by everyone as ''hijra'' or third sex, eunuchs earn their livelihood by dancing at the beat of drums and often resort to obscene postures but their pain and agony is not generally noticed and this demand is just a reminder of how helpless and neglected this section of society is. Thousands of welfare schemes have been launched by the government but these are only for men and women and third sex do not figure anywhere and this demand only showed mirror to society. The Constitution gives rights on the basis of citizenship and on the grounds of gender but the gross discrimination on the part of our legislature is evident. -

Failed Democratic Experience in Kyrgyzstan: 1990-2000 a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle Ea

FAILED DEMOCRATIC EXPERIENCE IN KYRGYZSTAN: 1990-2000 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY OURAN NIAZALIEV IN THE PARTIAL FULLFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION APRIL 2004 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences __________________________ Prof. Dr. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for degree of Master of Science __________________________ Prof. Dr. Feride Acar Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. __________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Pınar Akçalı Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assist. Prof. Dr. Pınar Akcalı __________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Canan Aslan __________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Oktay F. Tanrısever __________________________ ABSTRACT FAILED DEMOCRATIC EXPERIENCE IN KYRGYZSTAN: 1990-2000 Niazaliev, Ouran M.Sc., Department of Political Science and Public Administration Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Pınar Akçalı April 2004, 158 p. This study seeks to analyze the process of transition and democratization in Kyrgyzstan from 1990 to 2000. The collapse of the Soviet Union opened new political perspectives for Kyrgyzstan and a chance to develop sovereign state based on democratic principles and values. Initially Kyrgyzstan attained some progress in building up a democratic state. However, in the second half of 1990s Kyrgyzstan shifted toward authoritarianism. Therefore, the full-scale transition to democracy has not been realized, and a well-functioning democracy has not been established. -

(Mahalabiah& Serratia) Added to the Henna on Biochemical An

Besher et al, I. J. of Appl. Med. and Bio. Res. Vol 1 (2), 2016: p 16-22. ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Preliminary Study to Determine the Effects of Chemical solutions (Mahalabiah& Serratia) Added to the Henna on Biochemical and Hematological Parameters in white rabbits Maryam Mohamed Besher*, Aisha abokhzam, Rajaa Alghani. Medical laboratory Sciences Department, Faculty of Engineering& Technology, Sabha University/Libya. Received: July 2016, Accepted: September 2016 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Abstract The objective of the study was to determine the Influence of some chemical additives to Henna and most actively traded on some liver and kidney functions and complete blood count in white rabbits.15 rabbit divided into three groups, each group containing five rabbits. The first group which used as a control was a topical application of henna on the dorsal region of the rabbits after removing hair. The second group had been used henna with Mahlbaih. Henna was used with Serratia in third group. Rabbits were slaughter of after 24 hours to get the blood to require analyzes. The results of this study showed a significant increase in AST, ALT and increase in the concentration of Urea and Creatinine in the -

Sakina Mehndi Designs

+91-8048371610 Sakina Mehndi Designs https://www.indiamart.com/sakina-mehndi/ Mehndi or henna has been a popular form of skin decoration in Indian subcontinent countries like India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Although it is a very old practice in these countries, since 1990s it has also become popular in many western countries ... About Us Mehndi or henna has been a popular form of skin decoration in Indian subcontinent countries like India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Although it is a very old practice in these countries, since 1990s it has also become popular in many western countries being counterpart of tattoos. Mehndi is applied on some special occasions like Diwali, Teej, Eid, weddings, birthday parties and many other auspicious festivals. Mehndi design is applied on hands or feet of a woman and it is common that to apply henna on palms where due to presence of high levels of keratin the color appears in its dark form. Fresh henna leaves are grinded and oil is added to make cones which are used professionally for applying Mehndi designs. The origin of Mehndi as a part of celebration has been found to be of ancient Indian origin and beautiful patterns are still applied to brides at the time of wedding ceremonies. Although Mehndi design still refers to the common term of applying henna on the body parts, there exists various forms and types of designs that can be further categorized based on the features and their origins. The popular designs at present are found in the form of Rajasthani, Arabic, Pakistani, and Minakari etc. -

2019 International Religious Freedom Report

CHINA (INCLUDES TIBET, XINJIANG, HONG KONG, AND MACAU) 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary Reports on Hong Kong, Macau, Tibet, and Xinjiang are appended at the end of this report. The constitution, which cites the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party and the guidance of Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought, states that citizens have freedom of religious belief but limits protections for religious practice to “normal religious activities” and does not define “normal.” Despite Chairman Xi Jinping’s decree that all members of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) must be “unyielding Marxist atheists,” the government continued to exercise control over religion and restrict the activities and personal freedom of religious adherents that it perceived as threatening state or CCP interests, according to religious groups, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and international media reports. The government recognizes five official religions – Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Protestantism, and Catholicism. Only religious groups belonging to the five state- sanctioned “patriotic religious associations” representing these religions are permitted to register with the government and officially permitted to hold worship services. There continued to be reports of deaths in custody and that the government tortured, physically abused, arrested, detained, sentenced to prison, subjected to forced indoctrination in CCP ideology, or harassed adherents of both registered and unregistered religious groups for activities related to their religious beliefs and practices. There were several reports of individuals committing suicide in detention, or, according to sources, as a result of being threatened and surveilled. In December Pastor Wang Yi was tried in secret and sentenced to nine years in prison by a court in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, in connection to his peaceful advocacy for religious freedom. -

Research on Systemic Transformation in the Countries of Central Asia

POLISH POLITICAL SCIENCE YEARBOOK, vol. 49(3) (2020), pp. 111–133 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15804/ppsy2020307 PL ISSN 0208-7375 www.czasopisma.marszalek.com.pl/10-15804/ppsy Tadeusz Bodio University of Warsaw Committee of Political Science, Polish Academy of Science (Poland) ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8873-7434 e-mail: [email protected] Andrzej Wierzbicki University of Warsaw, Poland ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5493-164X e-mail: [email protected] Research on Systemic Transformation in the Countries of Central Asia Abstract: The article presents the goals, tasks, organization and major stages of implemen- tation of the international programme of research on transformation in the countries Cen- tral Asia. The research has been conducted since 1997 by a team of political scientists from the University of Warsaw in cooperation with representatives of other Polish and foreign universities. Keywords: Research programme, Central Asia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, political transformation, political tradition, political mod- ernization, ethnopolitics, velvet revolutions, post-communism 1. Preliminary Remarks The idea ofpolitical science research on political changes in Central Asia was spawned at the Institute of Political Science of the University of Warsaw in the 1990s, in the conditions of growing interest in cooperation with the newly created post-Soviet states and a huge deficit of knowledge about the region in which a significant Polish diaspora lived. In 1997, an intercol- legiate research team was established, conducting, together with scientists from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, research on changes taking place in the countries of the region (Deres, 2003). The team was organized on the initiative of Tadeusz Bodio, who was also the head of the international research programme. -

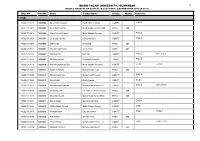

Faculty of Security & Strategic Studies

List of Eligible Candidates for Written Test Faculty/Program: Faculty of Security & Strategic Studies Session: Jan - Jun 2019 Count: 7128 SL# Name Father Name Quota Test Roll Military, Senate and 1 ,MD. SHAZZADUL KABIR MD. ANAMUL KABIR 1218192243 Syndicate Members 2 A B M MUSFIQUR RAHMAN MD MURAD HOSSAIN Not Applicable 1218194793 A K M RAZUNAL HOQUE Military, Senate and 3 MD SHAHIDUL ISLAM 1218196986 SHAGOR Syndicate Members Military, Senate and 4 A K M SAZZADUL ISLAM MD. SHAHIDUL ISLAM 1218195475 Syndicate Members 5 A K M TAIMUR SAKIB A K M AZIZUR RAHMAN Not Applicable 1218190443 Military, Senate and 6 A S M NAIMUR RAHMAN MD MOSHIUR RAHMAN 1218193266 Syndicate Members 7 A. B. M. NAHIN ALAM A. K. M. ZAHANGIR ALAM Not Applicable 1218194579 8 A. B. M. TAHMID AHABAB A. S. M. ATIQUR RAHMAN Freedom Fighter 1218190514 9 A. K. M LUTHFUL HAQUE A. K. M MONJURUL HAQUE Not Applicable 1218196529 10 A. K. M SAFAYAT NABIL A. K. M AKTARUZZAMAN Not Applicable 1218192772 A. K. M. MUNTASIR 11 A. K. M. AZAD Not Applicable 1218192608 MAHMUD 12 A. K. M. NAHID KHAN ALI AHMED KHAN Not Applicable 1218196224 13 A. K. M. NAHYAN ISLAM A. K. M. NURUL ISLAM Not Applicable 1218195082 Military, Senate and 14 A. N. M. ROBIN MD. FARUQUE HOSSAIN 1218193432 Syndicate Members 15 A. N. M. SAKIB MD. RUHUL AMIN Not Applicable 1218195033 16 A. S. M SHAFAYAT JAMIL A.B.M. HASAN SHAHID JAMIL Not Applicable 1218190372 A. S. M. AKIBUZZAMAN A. U. M. ATIKUZZAMAN 17 Not Applicable 1218193673 SARKER SHARKER Military, Senate and 18 A. -

Turkmen Language: Alphabet, Structure and Writing

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Growth Evaluation www.allmultidisciplinaryjournal.com International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Growth Evaluation ISSN: 2582-7138 Received: 03-07-2021; Accepted: 19-07-2021 www.allmultidisciplinaryjournal.com Volume 2; Issue 4; July-August 2021; Page No. 663-664 Turkmen Language: Alphabet, structure and writing Homayoun Mahmoodi Lecture, Department of Turkmani, Education Faculty, Jawzjan University, Sheberghan, Afghanistan Corresponding Author: Homayoun Mahmoodi Abstract The Turkmen Language is classified as one of the Turkic people worldwide, with approximately 1 million more languages which are all in the Ural-Altaic language family. speaking it as a second language. The majority of Turkmen Like all Turkic languages, the Turkmen Language is an speakers are located in Eurasia and Central Asia, with the agglutinative language that has productive inflectional and highest concentrations located in Turkmenistan, Iran, and derivational suffixes which are affixed to a word like “beads Afghanistan. on a string”. Turkmen is spoken natively by about 7 million Keywords: Turkmen, Afghanistan, Alphabet, structure 1. Introduction Turkmen are part of the ethno-linguistic Turkic continuum that stretches from western China to western Turkey. They share a claim to western-Turkic (Oguz) heritage along with Azerbaijanis and Turks in Turkey (Golden 1972) [4]. Despite a distinct twenty-first century identity, Turkmen culture and traditions historically overlapped with that of other Turks. The term “Turkic” refers to this cultural and linguistic heritage that all Turkic-language speaking groups share. Nevertheless, a separate Turkmen sense of identity was born out of their particular historical experience. A nomadic heritage, distinctively Oguz dialects, and tribal traditions contribute greatly to the identity that sets Turkmen apart from other Turkic groups and shape a specifically Turkmen sense of ethnic identity. -

QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD 18 RESULT GAZETTE of B.A/B.Sc./B.Com SUPPL

18 QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD RESULT GAZETTE OF B.A/B.Sc./B.Com SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2015 (Part-II) Reg. No. Roll No. Name Father Name Status Marks Remarks (002) 110021310011 3000002 Syed Afaq Hussain Syed Amin Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310001 3000003 Syed Atif Hussain Syed Sajid Hussain Shah PASS 430 110021310004 3000004 Mahr Ahmad Kamal Mahr Shabbir Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310006 3000005 Shahzad Ahmed Ashiq Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310007 3000006 Wali Khan Khowazik PASS 441 110021310013 3000007 Muhammad Ehsan Juma Khan PASS 437 110021310014 3000008 Mujahid Din Roz Din COMPT. ENG:II ENG-LIT:II 110021310015 3000009 Mehtab arshad Arshad Mehmood COMPT. ENG:II 110021310018 3000010 Mahr Muhammad Ijlal Mahr Shabbir Hussain COMPT. ECO:I ECO:II 110021310021 3000011 Sammar Abbas Muhammad Ismail PASS 436 110021310022 3000012 Muhammad Riaz Muhammad Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310026 3000013 Anas Ayaz Ayaz Ahmad COMPT. ECO:I 110021310027 3000014 Muhammad Shahzad Muhammad khursheed COMPT. ENG:II APP-PSY:II 110021310029 3000015 Shahab U Din Ch Zaheer Ud Din Ahmed PASS 384 110021310031 3000016 Muzaffar Sultan Muhammad Sultan Khan PASS 453 110021310033 3000017 Sohail Iqbal Muhammad Iqbal COMPT. ENG:II 110021310034 3000018 Malik Waqar Ahmed Malik Iftikhar Ahmad COMPT. ENG:I 110021310035 3000019 Waqar Haider Ghulam Haider COMPT. ENG:I ENG:II 110021310036 3000020 Arif Zaman Mehran Khan PASS 434 110021310038 3000021 Fahad Raza Muhammad Muslimeen COMPT. ENG:I ENG-LIT:II 110021310039 3000022 Mubasher Nawaz Muhammad Nawaz PASS 423 19 QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD RESULT GAZETTE OF B.A/B.Sc./B.Com SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2015 (Part-II) Reg. -

Death-Penalty-Pakistan

Report Mission of Investigation Slow march to the gallows Death penalty in Pakistan Executive Summary. 5 Foreword: Why mobilise against the death penalty . 8 Introduction and Background . 16 I. The legal framework . 21 II. A deeply flawed and discriminatory process, from arrest to trial to execution. 44 Conclusion and recommendations . 60 Annex: List of persons met by the delegation . 62 n° 464/2 - January 2007 Slow march to the gallows. Death penalty in Pakistan Table of contents Executive Summary. 5 Foreword: Why mobilise against the death penalty . 8 1. The absence of deterrence . 8 2. Arguments founded on human dignity and liberty. 8 3. Arguments from international human rights law . 10 Introduction and Background . 16 1. Introduction . 16 2. Overview of death penalty in Pakistan: expanding its scope, reducing the safeguards. 16 3. A widespread public support of death penalty . 19 I. The legal framework . 21 1. The international legal framework. 21 2. Crimes carrying the death penalty in Pakistan . 21 3. Facts and figures on death penalty in Pakistan. 26 3.1. Figures on executions . 26 3.2. Figures on condemned prisoners . 27 3.2.1. Punjab . 27 3.2.2. NWFP. 27 3.2.3. Balochistan . 28 3.2.4. Sindh . 29 4. The Pakistani legal system and procedure. 30 4.1. The intermingling of common law and Islamic Law . 30 4.2. A defendant's itinerary through the courts . 31 4.2.1. The trial . 31 4.2.2. Appeals . 31 4.2.3. Mercy petition . 31 4.2.4. Stays of execution . 33 4.3. The case law: gradually expanding the scope of death penalty .