Champions for Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faculty of Security & Strategic Studies

List of Eligible Candidates for Written Test Faculty/Program: Faculty of Security & Strategic Studies Session: Jan - Jun 2019 Count: 7128 SL# Name Father Name Quota Test Roll Military, Senate and 1 ,MD. SHAZZADUL KABIR MD. ANAMUL KABIR 1218192243 Syndicate Members 2 A B M MUSFIQUR RAHMAN MD MURAD HOSSAIN Not Applicable 1218194793 A K M RAZUNAL HOQUE Military, Senate and 3 MD SHAHIDUL ISLAM 1218196986 SHAGOR Syndicate Members Military, Senate and 4 A K M SAZZADUL ISLAM MD. SHAHIDUL ISLAM 1218195475 Syndicate Members 5 A K M TAIMUR SAKIB A K M AZIZUR RAHMAN Not Applicable 1218190443 Military, Senate and 6 A S M NAIMUR RAHMAN MD MOSHIUR RAHMAN 1218193266 Syndicate Members 7 A. B. M. NAHIN ALAM A. K. M. ZAHANGIR ALAM Not Applicable 1218194579 8 A. B. M. TAHMID AHABAB A. S. M. ATIQUR RAHMAN Freedom Fighter 1218190514 9 A. K. M LUTHFUL HAQUE A. K. M MONJURUL HAQUE Not Applicable 1218196529 10 A. K. M SAFAYAT NABIL A. K. M AKTARUZZAMAN Not Applicable 1218192772 A. K. M. MUNTASIR 11 A. K. M. AZAD Not Applicable 1218192608 MAHMUD 12 A. K. M. NAHID KHAN ALI AHMED KHAN Not Applicable 1218196224 13 A. K. M. NAHYAN ISLAM A. K. M. NURUL ISLAM Not Applicable 1218195082 Military, Senate and 14 A. N. M. ROBIN MD. FARUQUE HOSSAIN 1218193432 Syndicate Members 15 A. N. M. SAKIB MD. RUHUL AMIN Not Applicable 1218195033 16 A. S. M SHAFAYAT JAMIL A.B.M. HASAN SHAHID JAMIL Not Applicable 1218190372 A. S. M. AKIBUZZAMAN A. U. M. ATIKUZZAMAN 17 Not Applicable 1218193673 SARKER SHARKER Military, Senate and 18 A. -

QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD 18 RESULT GAZETTE of B.A/B.Sc./B.Com SUPPL

18 QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD RESULT GAZETTE OF B.A/B.Sc./B.Com SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2015 (Part-II) Reg. No. Roll No. Name Father Name Status Marks Remarks (002) 110021310011 3000002 Syed Afaq Hussain Syed Amin Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310001 3000003 Syed Atif Hussain Syed Sajid Hussain Shah PASS 430 110021310004 3000004 Mahr Ahmad Kamal Mahr Shabbir Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310006 3000005 Shahzad Ahmed Ashiq Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310007 3000006 Wali Khan Khowazik PASS 441 110021310013 3000007 Muhammad Ehsan Juma Khan PASS 437 110021310014 3000008 Mujahid Din Roz Din COMPT. ENG:II ENG-LIT:II 110021310015 3000009 Mehtab arshad Arshad Mehmood COMPT. ENG:II 110021310018 3000010 Mahr Muhammad Ijlal Mahr Shabbir Hussain COMPT. ECO:I ECO:II 110021310021 3000011 Sammar Abbas Muhammad Ismail PASS 436 110021310022 3000012 Muhammad Riaz Muhammad Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310026 3000013 Anas Ayaz Ayaz Ahmad COMPT. ECO:I 110021310027 3000014 Muhammad Shahzad Muhammad khursheed COMPT. ENG:II APP-PSY:II 110021310029 3000015 Shahab U Din Ch Zaheer Ud Din Ahmed PASS 384 110021310031 3000016 Muzaffar Sultan Muhammad Sultan Khan PASS 453 110021310033 3000017 Sohail Iqbal Muhammad Iqbal COMPT. ENG:II 110021310034 3000018 Malik Waqar Ahmed Malik Iftikhar Ahmad COMPT. ENG:I 110021310035 3000019 Waqar Haider Ghulam Haider COMPT. ENG:I ENG:II 110021310036 3000020 Arif Zaman Mehran Khan PASS 434 110021310038 3000021 Fahad Raza Muhammad Muslimeen COMPT. ENG:I ENG-LIT:II 110021310039 3000022 Mubasher Nawaz Muhammad Nawaz PASS 423 19 QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD RESULT GAZETTE OF B.A/B.Sc./B.Com SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2015 (Part-II) Reg. -

Death-Penalty-Pakistan

Report Mission of Investigation Slow march to the gallows Death penalty in Pakistan Executive Summary. 5 Foreword: Why mobilise against the death penalty . 8 Introduction and Background . 16 I. The legal framework . 21 II. A deeply flawed and discriminatory process, from arrest to trial to execution. 44 Conclusion and recommendations . 60 Annex: List of persons met by the delegation . 62 n° 464/2 - January 2007 Slow march to the gallows. Death penalty in Pakistan Table of contents Executive Summary. 5 Foreword: Why mobilise against the death penalty . 8 1. The absence of deterrence . 8 2. Arguments founded on human dignity and liberty. 8 3. Arguments from international human rights law . 10 Introduction and Background . 16 1. Introduction . 16 2. Overview of death penalty in Pakistan: expanding its scope, reducing the safeguards. 16 3. A widespread public support of death penalty . 19 I. The legal framework . 21 1. The international legal framework. 21 2. Crimes carrying the death penalty in Pakistan . 21 3. Facts and figures on death penalty in Pakistan. 26 3.1. Figures on executions . 26 3.2. Figures on condemned prisoners . 27 3.2.1. Punjab . 27 3.2.2. NWFP. 27 3.2.3. Balochistan . 28 3.2.4. Sindh . 29 4. The Pakistani legal system and procedure. 30 4.1. The intermingling of common law and Islamic Law . 30 4.2. A defendant's itinerary through the courts . 31 4.2.1. The trial . 31 4.2.2. Appeals . 31 4.2.3. Mercy petition . 31 4.2.4. Stays of execution . 33 4.3. The case law: gradually expanding the scope of death penalty . -

Institute of Business Administration, Karachi Bba, Bs

FINAL RESULT - FALL 2020 ROUND 1 Announced on Tuesday, February 25, 2020 INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, KARACHI BBA, BS (ACCOUNTING & FINANCE), BS (ECONOMICS) & BS (SOCIAL SCIENCES) ADMISSIONS TEST HELD ON SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2020 (FALL 2020, ROUND 1) LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR DIRECT ADMISSION (BSAF PROGRAM) SAT Test Math Eng TOTAL Maximum Marks 800 800 1600 Cut-Off Marks 600 600 1410 Math Eng Total IBA Test MCQ MCQ MCQ Maximum Marks 180 180 360 Cut-Off Marks 100 100 256 Seat S. No. App No. Name Father's Name No. 1 18 845 FABIHA SHAHID SHAHIDSIDDIQUI 132 136 268 2 549 1510 MUHAMMAD QASIM MAHMOOD AKHTAR 148 132 280 3 558 426 MUHAMMAD MUTAHIR ABBAS AMAR ABBAS 144 128 272 4 563 2182 ALI ABDULLAH MUHAMMAD ASLAM 136 128 264 5 1272 757 MUHAMMAD DANISH NADEEM MUHAMMAD NADEEM TAHIR 136 128 264 6 2001 1 MUHAMMAD JAWWAD HABIB MUHAMMAD NADIR HABIB 160 100 260 7 2047 118 MUHAMMAD ANAS LIAQUAT ALI 148 128 276 8 2050 125 HAFSA AZIZ AZIZAHMED 128 136 264 9 2056 139 MUHAMMAD SALMAN ANWAR MUHAMMAD ANWAR 156 132 288 10 2086 224 MOHAMMAD BADRUDDIN RIND BALOCH BAHAUDDIN BALOCH 144 112 256 11 2089 227 AHSAN KAMAL LAGHARI GHULAM ALI LAGHARI 136 160 296 12 2098 247 SYED MUHAMMAD RAED SYED MUJTABA NADEEM 152 132 284 13 2121 304 AREEB AHMED BAIG ILHAQAHMED BAIG 108 152 260 14 2150 379 SHAHERBANO ‐ ABDULSAMAD SURAHIO 148 124 272 15 2158 389 AIMEN ATIQ SYED ATIQ UR REHMAN 148 124 272 16 2194 463 MUHAMMAD SAAD MUHAMMAD ABBAS 152 136 288 17 2203 481 FARAZ NAWAZ MUHAMMAD NAWAZ 132 128 260 18 2210 495 HASNAIN IRFAN IRFAN ABDULAZIZ 128 132 260 19 2230 -

FACULTY : COLLEGE : 1 of Page SINDH E-CENTRALIZED

SINDH E-CENTRALIZED COLLEGE ADMISSION POLICY 2017 PLACEMENT IN XI ON MERIT UNDER SECCAP-2017 PRINT DATE : 04/09/2017 FACULTY : Pre-Engineering - Female Page 1 of 9 COLLEGE : 201 ABDULLAH GOVT. COLLEGE FOR WOMEN KARACHI ADMISSION START AT = 751 ADMISSION CLOSED AT = 591 # ROLL - YEAR Name Marks 1 483160 - 2017 TOOBA SHAKIL D/O SHAKIL AKHTAR 751 2 483179 - 2017 NADIA SALEEM D/O MUHAMMAD SALEEM 742 3 470543 - 2017 AQSA SHERAZ D/O MUHAMMAD KHALID SHEROZ 739 4 483178 - 2017 MISBAH D/O ABDUL RAOOF 737 5 481587 - 2017 AYESHA D/O MUHAMMAD IQBAL 724 6 483165 - 2017 FAZEELA QADIR D/O ABDUL QADIR 722 7 484420 - 2017 SAMINA D/O SHAMIM AKHTER 714 8 433353 - 2017 DANIA AHMED D/O SALAHUDDIN AHMED QURAISHI 713 9 439093 - 2017 FABIHA IKHLAQ D/O MUHAMMAD IKHLAQ 709 10 444873 - 2017 FABIHA NADIR D/O NADIR MUHAMMAD QURESHI 708 11 484046 - 2017 AYESHA FAROOQ D/O MUHAMMAD FAROOQ 708 12 432060 - 2017 KHADIJA D/O FAKHRUDDIN 708 13 433941 - 2017 MARIA MEHMOOD D/O MEHMOOD ASHRAF 706 14 446166 - 2017 BIBI IQRA D/O SHAKEEL AHMED 705 15 485623 - 2017 MUBASHRA SABIR D/O SABIR AHMED 705 16 478101 - 2017 NAYAB SHAH D/O SYED WAQAR HUSSAIN SHAH 704 17 484023 - 2017 MISBAH ANSARI D/O IKHLAQ AHMED 704 18 429700 - 2017 HAREEM BINT E ZIA D/O AHMED ZIA UDDIN 703 19 430944 - 2017 NIMRA KHANUM D/O MUHAMMAD SHARIF ULLAH KHAN 703 20 478099 - 2017 IRSA D/O GHULAM RASOOL 702 21 479586 - 2017 DUA ZAHRA JAFRI D/O AZHAR ABBAS JAFRI 702 22 484249 - 2017 MARIA NOUREEN D/O SHAFI ALAM 702 23 477809 - 2017 MARIYAM D/O MUHAMMAD ISHAQ 701 24 482955 - 2017 LAIBA ISLAM RANA D/O SHOUKAT ISLAM -

IGI Insurance Limited

ANNUAL REPORT 2007 IGI Insurance Limited Flowering Trees of Pakistan People are caring for and planting more trees because ecological awareness has prompted many ofustoseeintreesthebestand surest living antidote to restoring the equilibrium of Mother Nature. Treesremaintheguardiansofour soil and water, the refuges of wild life,andtheprovidersofmany things. It is their grace and form, their silent almost timeless vigil, their links with the past, their hopes for the future which give treesaspecialattractiontous. IGI Insurance Report 2007 is dedicated to some of the flowering treesthataregrowninPakistan. CONTENTS Vision / Mission Statement 2 Quality Policy 3 Company Information 4 Management Information 6 Introduction 7 Key Financial Data 19 Shareholders’ Information 22 Directors’ Report to the Shareholders 30 Statement of Compliance with the Code of Corporate Governance 36 Review Report to the Members on Statement of Compliance with Best Practices of Code of Corporate Governance 38 Auditors’ Report to the Members 39 Balance Sheet 40 Profit and Loss Account 42 Statement of Changes in Equity 43 Cash Flow Statement 44 Statement of Premiums 46 Statement of Claims 47 Statement of Expenses 48 Statement of Investment Income 49 Notes to the Financial Statements 50 Notice of Annual General Meeting 80 Form of Proxy VISION QUALITY POLICY IGI Insurance is committed to being one of the leading providers of solutions to risk exposures in IGI Insurance believes in providing selected market segments high quality solutions to risk in Pakistan. exposures -

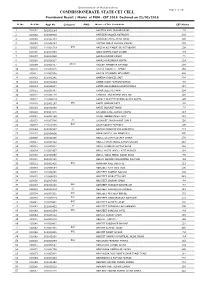

Provisional Result/Marks for PGM-CET 2016

Government of Maharashtra COMMISSIONERATE, STATE CET CELL Page 1 of 181 Provisional Result / Marks of PGM - CET 2016 Declared on 22/02/2016 Sr.No. Roll No. Appl No. Category PWD Name of The Candidate CET Marks 1 100001 161003184 AADITYA ANIL PRABHUDESAI 178 2 100002 161006430 AAFREEN NASSER KOTADIYA 201 3 100003 161011484 AAFREEN KAMAL AHAD AHAD 106 4 100004 161008664 AAFTAB ABRAR HUSAIN ANSARI 172 5 100005 161001529 OBC AAISHA ASHFAQUE GULREZ QADRI 109 6 100006 161009859 AAISHWARYA DILIP DHABE 159 7 100007 161003430 AAKASH RAJEN DOSHI 176 8 100008 161006337 AAKASH RAJENDRA GUPTA 124 9 100009 161001417 DT(VJ) AALEKH MANOHAR RATHOD 209 10 100010 161002045 AALIYA ASGAR ALI AFROZ 158 11 100011 161006308 AALIYA MEHMOOD MEHMOOD 208 12 100012 161001241 AAMERA SHAKEEL SAIT 228 13 100013 161002244 AAMIR JAKIR PATHAN PATHAN 165 14 100014 161006587 AAMIR ASHFAQUE BHARAPURWALA 117 15 100015 161000797 AAMIR JEELANI KHAN 204 16 100016 161000178 AANCHAL ANILKUMAR GVALANI 116 17 100017 161004219 AARSHI PRADEEP KUMAR GUPTA GUPTA 190 18 100018 161002167 OBC AARTI SOMVAR PATIL 188 19 100019 161001689 AARTI INDRAJIT MORE 176 20 100020 161007075 AARZOO SUNIL KUMAR VERMA 113 21 100021 161008750 AASHI ABOOBACKER AKAY 121 22 100022 161003786 SC AASHIKET SHASHIKANT SABLE 116 23 100023 161010785 OBC AASIM QASIM TAMBOLI 100 24 100024 161010517 AAYUSH PRADEEP KULSHRESTHA 213 25 100025 161004816 ABBAS HIBTULLAH MOAIYADI 205 26 100026 161010396 ABDUL GULAM MUSTAFA RAHUP 178 27 100027 161008422 ABDUL FAHIM ABDUL RAHIM SHAIKH 248 28 100028 161007061 ABDUL MANNAN SATTAR -

F.Sc Pre-Medical Final Open Merit List, Jinnah College for Women Session 2015-16

F.Sc Pre-Medical Final Open Merit List, Jinnah College for Women Session 2015-16 Documents S.No Form No. Student's Name Father's Name Marks Remarks Required 1 1397 Nimra Ehsan Ehsan Gul Khattak 1072 2 1970 Ruqiya Saeed Saeed Iqbal 1063 3 2187 Syeda Mariam Noor Asif Salman 1058 4 1323 Humaira Javed Khan 1056 5 2145 Hira Kamran Muhammad Karmran Shafi 1050 6 1919 Ayesha Ahmad Nayyar Ahmad 1047 7 885 Sumayya Muhammad Ashfaq Khan 1043 8 904 Sumaiya Mustafa Ghulam Mustafa 1042 9 1085 Umama Faisal Akhunzada Ahmad Saeed Akhunzada 1041 10 1018 Mashal Shahid Shahid Ahmad Khalil 1040 11 1113 Malghalara Suleman Amir Suleman 1037 12 223 Sana Hussain Hazrat Hussain 1036 13 2348 Omama Naeem Naeem Mumtaz 1035 14 2202 Saneea Sufian Muhammad Sufian Samad 1035 15 1228 Manahil Hassan Mohammad Hassan Khan 1035 16 897 Araish Noor Shehzadi Rooh Ullah 1034 17 728 Ayesha Gul Mumtaz Khan 1034 18 2252 Muneeba Amin Amin Khan 1033 19 719 Mana Hil Ayub Khan 1033 20 29 Marwah Kifayat Kifayat Ullah 1032 20 Marks Hafiz Quran 21 1577 Anam Qazi Qazi Anwar Ul Haq 1032 22 591 Zarmeena Ajmal Muhammad Ajmal Khan 1031 23 1813 Saffa Rashid Abdur Rashid 1031 20 Marks Hafiz 24 972 Summan Naheed Masroor Asim 1031 Quran 25 1489 Sawera Ali Meer Shaukat Ali Meer 1031 26 658 Sundas Shafqat Shafqat Yar Khan 1030 27 2003 Hafsa Humayun Dr Humayun 1029 20 Marks Hafiz 28 1863 Hafiza Marwa Farooq Umar Farooq 1029 Quran 29 2041 Naveed E Sahar Safdar Khan 1028 30 1737 Farah Afsheen Muhammad Javaid 1028 31 1690 Shabnam Zia Zia Jan Khan 1028 32 2005 Aqsa Kunwal Ali Ahmad Ali 1028 33 739 Warda Haleem Haleem Muhammad 1028 34 1903 Mutahira Khawaja Muhammad Khalid Khwaja 1028 Matric DMC 35 975 Saima Kamal Syed Kamal Shah Jadoon 1028 Photo copy required 36 2288 Sadia Wahid Abdul Wahid 1028 37 178 Irsa Sikandar Sikandar Khan 1027 38 1619 Zarghoona Shah Ajmali Shah 1027 39 978 Umama Qayyum Abdul Qayyum 1027 40 1906 Sumbal Zubair Muhammad Zubair 1027 41 140 Asma Ali Ghulam Ali Bajwa 1026 42 2341 Kainat Fida Fida Muhammad 1026 43 327 Hafsa Maqsood Maqsood Ahmad 1025 44 234 S. -

6455.Pdf, PDF, 1.27MB

Overall List Along With Domicile and Post Name Father Name District Post Shahab Khan Siraj Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sana Ullah Muhammad Younas Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Mahboob Ali Fazal Rahim Swat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tahir Saeed Saeed Ur Rehman Kohat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Owais Qarni Raham Dil Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Ashfaq Ahmad Zarif Khan Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Saud Khan Haji Minak Khan Khyber 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Qamar Jan Syed Marjan Kurram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Kamil Khan Wakeel Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Waheed Gul Muhammad Qasim Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tanveer Ahmad Mukhtiar Ahmad Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Faheem Muhammad Aslam PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muslima Bibi Jan Gul Dera Ismail Khan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Zahid Muhammad Saraf Batagram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Riaz Khan Muhammad Anwar Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Bakht Taj Abdul Khaliq Shangla 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Hidayat Ullah Fazal Ullah Swabi 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Wajid Ali Malang Jan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sahar Rashed Abdur Rasheed Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Afsar Khan Afridi Ghulam Nabi PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Khan Manazir Khan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Liaqat Ali Malik Aman Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Iqbal Parvaiz Khan Mardan 01. -

First Pak Modarab 14Th Dividend Unpaid Detail As on 31.12.2020

FIRST PAK MODARABA UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND D-14 2019-20 WARRANT NOS FOLIO NAME OF SHARE HOLDERS AMOUNT OF DIVIDEND STATUS 140001 1 MRS. ZOHRA BAI 10.00 UNPAID 140002 3 MR. GULNOOR 26.00 UNPAID 140003 10 MST. AMIR KHANUM 5.00 UNPAID 140004 14 MR. MOHAMMAD KHAN LODHI 26.00 UNPAID 140005 26 MR. MOHD SALIM MANSOORI 26.00 UNPAID 140006 27 MR. AFAQ ALI 2.00 UNPAID 140007 29 MR. ABBAS 6.00 UNPAID 140008 32 MR. SIRAJ 7.00 UNPAID 140009 33 MR. MOHAMMAD AFAQ 7.00 UNPAID 140010 41 MR. S. SHAKIL ASHRAF 1.00 UNPAID 140011 45 MR. A. SATTAR KAMDAR 24.00 UNPAID 140012 46 MRS. HAMIDA BANOO 24.00 UNPAID 140013 83 MR. MOHD HANIF 2.00 UNPAID 140014 84 MR. GHULAM ABBAS 2.00 UNPAID 140015 86 MRS. KAUSAR PARVEEN 6.00 UNPAID 140016 90 MR. MUSHTAQ 10.00 UNPAID 140017 92 MRS. NASERA BANO 2.00 UNPAID 140019 100 MST. FARIDA YAQOOB ABDUL SATTAR 1.00 UNPAID 140020 103 MR. MOHAMMED YOUSUF 26.00 UNPAID 140021 116 MRS. ZAHID BEGUM 11.00 UNPAID 140022 123 MRS. ZARINA SULTAN 2.00 UNPAID 140023 125 MR. FAZAL MAHMOOD 2.00 UNPAID 140024 131 MISS ZAHIDA PERVEEN 6.00 UNPAID 140025 137 SYED AZIZ AHMED 6.00 UNPAID 140026 157 MRS. KULSOOM 6.00 UNPAID 140027 162 MR. ABDUL RASHEED 26.00 UNPAID 140028 181 MRS. YASMIN 26.00 UNPAID 140029 194 MR. ANIS AHMAD KHALID 6.00 UNPAID 140030 198 MR. ISMAIL VOHRA 26.00 UNPAID 140031 199 MR. ZAKARIA UMAR 6.00 UNPAID 140032 200 MR. -

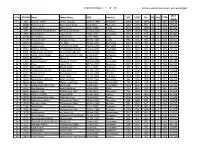

Errors and Ommissions Are Accepted

Merit list (Open) 1 of 72 Errors and ommissions are accepted. Merit S.No ETEA ID Name Father Name DOB Domicile SSC T/SSC FSc HQ Ded ETEA Score 1 89 Ibrahim Akhtar Akhtar Hussain 12-Nov-1999 Peshawar 1018 1100 1000 0 0 656 86.618 2 22608 Syed Saad Ali Syed Abdul Wajid 8-Jul-2000 Mansehra 1001 1100 993 0 0 661 86.522 3 6007 Umair Hayat Omer Hayat 1-Mar-2000 Swabi 1021 1100 1009 0 0 647 86.410 4 3092 MUQTASID AFTAB KHAN AFTAB ALAM KHAN 27-May-2000 Peshawar 1009 1050 974 0 0 658 86.153 5 2902 Mashal khan Hayat Ullah 2-Mar-2001 Charsadda 1015 1100 977 0 0 658 85.880 6 32775 Sheraz Khan Sohrab Khan 4-Oct-1999 Swat 1021 1100 998 0 0 644 85.823 7 51220 Khizar Ahmad Haroon Ahmad 10-Mar-2001 Swabi 990 1100 966 0 0 662 85.502 8 22915 Fizza Hassan Mir Afzal 15-Oct-1999 Mansehra 1013 1100 989 0 0 640 85.173 9 21572 Zainab Javed Muhammad Javed 28-May-1998 Mansehra 1004 1100 991 0 0 638 85.039 10 22365 KHKULA KAMAL MUHAMMAD KAMAL 22-Aug-2000 Charsadda 1016 1050 1031 0 0 602 84.792 11 6496 Rafia Hassan Jahangiri Hassan Riaz Jahangiri 13-Aug-2000 Peshawar 1003 1050 976 0 0 628 84.293 12 51003 Syeda Fatima Sajjad Syed Sajjad Hamid Zaidi 1-Aug-2001 Nowshera 1026 1050 990 0 0 616 84.271 13 20560 Majid Khan Bahar Ali 8-Aug-1999 Swabi 1000 1050 1018 0 0 603 84.229 14 1631 Maria Maqsood Maqsood Ahmad 18-May-2000 Charsadda 1038 1100 1013 0 0 606 84.148 15 8423 Hifsa Hakim Khan 10-Feb-2000 Nowshera 1017 1100 997 0 0 618 84.125 16 8777 ABU BAKKAR ZAFAR KHAN 6-Sep-1999 Peshawar 974 1050 984 0 0 623 83.996 17 22029 muhammad kamran zarhad khan 12-Mar-2001 Mansehra -

Transgender People and Human Rights Issues in Pakistan

Transgender People and Human Rights Issues in Pakistan Muhammad Ali Awan Institut für Ethnologie (Anthropologie) Philosophie und Geschichtswissenschaften Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main Deutschland 2019 Transgender People and Human Rights Issues in Pakistan Muhammad Ali Awan Thesis submitted to the Institute of Ethnology (Anthropology) for the partial fulfilment of the award of PhD Degree in Anthropology Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology Faculty 8 | Philosophy and History Johann Wolfgang Goethe University, Frankfurt/Main Germany 2019 i ii Contents Acronyms .................................................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgement .................................................................................................................... vi Abstract .................................................................................................................................... vii Chapter 1: The Position of Hijra (Transgender) People: From Past to Present ..................... 1 Chapter 2: Research Methodology ...................................................................................... 44 Chapter 3: Socioeconomic and Demographic Profiling of Hijra People and Types of Hijra Identities ............................................................................................................................ 73 Chapter 4: Gender of Gender Variant Child .....................................................................