The Pole Who Tried to Free Jefferson's Slaves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2012 I'm Really Just an American: The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness Shea Aisha Winsett College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Winsett, Shea Aisha, "I'm Really Just an American: The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness" (2012). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626687. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-tesy-ns27 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I’m Really Just An American: The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness Shea Aisha Winsett Hyattsville, Maryland Bachelors of Arts, Oberlin College, 2008 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department -

FACING the CHANGE CANADA and the INTERNATIONAL DECADE for PEOPLE of AFRICAN DESCENT Special Edition in Partnership with the Canadian Commission for UNESCO

PART 1 FACING THE CHANGE CANADA AND THE INTERNATIONAL DECADE FOR PEOPLE OF AFRICAN DESCENT Special Edition in Partnership with the Canadian Commission for UNESCO VOLUME 16 | NO. 3 | 2019 YEMAYA Komi Olaf SANKOFA EAGLE CLAN Komi Olaf PART ONE “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced” – James Baldwin INTRODUCTION FACING THE FINDINGS Towards Recognition, Justice and Development People of African Descent in Canada: 3 Mireille Apollon 32 A Diversity of Origins and Identities Jean-Pierre Corbeil and Hélène Maheux Overview of the Issue 5 Miriam Taylor Inflection Point – Assessing Progress on Racial Health Inequities in Canada During the Decade for 36 People of African Descent FACING THE CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES Tari Ajadi OF THE INTERNATIONAL DECADE What the African American Diaspora can Teach Us A Decade to Eradicate Discrimination and the 39 about Vernacular Black English Scourge of Racism: National Black Canadians Dr. Shana Poplack 9 Summits Take on the Legacy of Slavery The Right Honourable Michaëlle Jean THE FACE OF LIVED EXPERIENCE Unique Opportunities and Responsibilities 13 of the International Decade The Black Experience in the Greater Toronto Area The Honourable Dr. Jean Augustine 46 Dr. Wendy Cukier, Dr Mohamed Elmi and Erica Wright Count Us In: Nova Scotia’s Action Plan in Response Challenging Racism Through Asset Mapping and to the International Decade for People of African Case Study Approaches: An Example from the 16 Descent, 2015-2024 49 African Descent Communities in Vancouver, BC Wayn Hamilton Rebecca Aiyesa and Dr. Oleksander (Sasha) Kondrashov Migration, Identity and Oppression: An Inter-provincial Community Initiative Exploring FACING THE LEGACY OF COLONIALISM and Addressing the Intersectionality of Oppression and Related Health, Social and Economic Costs The Sun Never Sets, The Sun Waits to Rise: 53 The Enduring Structural Legacies of European Dr. -

HS, African American History, Quarter 1

2021-2022, HS, African American History, Quarter 1 Students begin a comprehensive study of African American history from pre1619 to present day. The course complies T.C.A. § 49-6-1006 on inclusion of Black history and culture. Historical documents are embedded in the course in compliance with T.C.A. § 49-6-1011. The Beginnings of Slavery and the Slave Trade - pre-1619 State Standards Test Knowledge Suggested Learning Suggested Pacing AAH.01 Analyze the economic, The economic, political, and Analyze and discuss reasons for political, and social reasons for social reasons for colonization the focusing the slave trade on focusing the slave trade on and why the slave trade focused Africa, especially the natural Africa, including the roles of: on Africans. resources, labor shortages, and Africans, Europeans, and religion. 1 Week Introduction The role Africans, Europeans, and colonists. colonist played in the slave trade. Analyze the motivations of Africans, Europeans, and colonists to participate in slave trading. AAH.02 Analyze the role of The geography of Africa including Analyze various maps of Africa geography on the growth and the Sahara, Sahel, Ethiopian including trade routes, physical development of slavery. Highlands, the savanna (e.g., geography, major tribal location, Serengeti), rainforest, African and natural resources. Great Lakes, Atlantic Ocean, Use Exploring Africa Website to Mediterranean Sea, and Indian understand previous uses of Ocean. 1 Week slavery and compare to European Deep Dive into The impact of Africa’s geography slave trade. African Geography on the development of slavery. Compare the practice of slavery Identify the Igbo people. between the internal African slave trade, slave trade in Europe Comparisions of the Trans- during the Middle Ages, the Saharan vs Trans-Atlantic. -

How Did Forced Migration and Forced Displacement Change Igbo Women’S and Their African American Daughters’ Environmental Identity?

How Did Forced Migration and Forced Displacement Change Igbo Women’s and Their African American Daughters’ Environmental Identity? A THESIS Presented to the Urban Sustainability Department Antioch University, Los Angeles In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Urban Sustainability Capstone Committee Members: Susan Gentile, MS. Jane Paul, MA. Susan Clayton, Ph.D. Submitted by Jamila K. Gaskins April 2018 Abstract Environmental identity and forced migration are well-researched subjects, yet, the intergenerational effects of forced migration on environmental identity lack substantive examination. This paper explores and adds to that research by asking the question, how did forced migration and forced displacement change Igbo women’s and their African American daughter's environmental identity? The Igbo women were kidnapped from Igboland (modern-day Nigeria) for sale in the transatlantic slave trade. A significant percentage of the Igbo women shipped to colonial America were taken to the Chesapeake colonies. Historians indicate that Igbo women were important in the birth of a new generation of African Americans due to the high number of their children surviving childbirth. One facet of environmental identity is place identity, which can be an indicator of belonging. This paper investigates the creation of belonging in the midst of continued, generational disruption in the relationship to the land, or environmental identity. Historical research and an extensive literature review were the research methods. It was concluded that stating a historical environmental identity with any scientific validity is not possible. Instead, there is a reason to suggest a high level of connection between cultural identity and the environmental identity of the Igbo before colonization and enslavement by colonial Americans. -

African Names and Naming Practices: the Impact Slavery and European

African Names and Naming Practices: The Impact Slavery and European Domination had on the African Psyche, Identity and Protest THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Liseli A. Fitzpatrick, B.A. Graduate Program in African American and African Studies The Ohio State University 2012 Thesis Committee: Lupenga Mphande, Advisor Leslie Alexander Judson Jeffries Copyrighted by Liseli Anne Maria-Teresa Fitzpatrick 2012 Abstract This study on African naming practices during slavery and its aftermath examines the centrality of names and naming in creating, suppressing, retaining and reclaiming African identity and memory. Based on recent scholarly studies, it is clear that several elements of African cultural practices have survived the oppressive onslaught of slavery and European domination. However, most historical inquiries that explore African culture in the Americas have tended to focus largely on retentions that pertain to cultural forms such as religion, dance, dress, music, food, and language leaving out, perhaps, equally important aspects of cultural retentions in the African Diaspora, such as naming practices and their psychological significance. In this study, I investigate African names and naming practices on the African continent, the United States and the Caribbean, not merely as elements of cultural retention, but also as forms of resistance – and their importance to the construction of identity and memory for persons of African descent. As such, this study examines how European colonizers attacked and defiled African names and naming systems to suppress and erase African identity – since names not only aid in the construction of identity, but also concretize a people’s collective memory by recording the circumstances of their experiences. -

Race in (Inter) Action: Identity Work and Interracial Couples' Navigation

Race in (Inter)Action: Identity Work and Interracial Couples’ Navigation of Race in Everyday Life A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School at the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of Sociology of the College of Arts and Sciences by Ainsley E. Lambert-Swain B.A., Morehead State University, 2009 M.A., University of Cincinnati, 2013 Dissertation Chair: Jennifer Malat Committee Members: Littisha Bates Sarah Mayorga-Gallo July 2018 ABSTRACT Interracial couples are a growing population in the United States. In 1967, after the Loving v. Virginia Supreme Court case ended all legal restrictions of interracial sex and marriage, just 3% of newlyweds were interracial. In 2015, approximately fifty years later, the percentage of interracially married newlyweds was more than five times that amount. This increase is even higher when non-married and non-heterosexual couples are accounted for. At the same time, the U.S. remains highly segregated by race. This means that interracial couples often move between racially homogenous settings wherein either partner is the only member of their race. Consequently, couples must navigate shifting racial meanings as they traverse racial boundaries in their everyday lives. Using in-depth interviews with 40 partners in White/non-White interracial relationships, this study examines the identity processes involved as couples navigate race and racism in interaction. Findings shed light on couples’ struggle to assess how their interraciality shapes the way they are perceived by others in a highly racialized society; how White partners, who experience racial salience often for the first time, consciously manage their identity in non- White spaces; and how White partners make sense of the racism they observe from other Whites in their social worlds. -

The Force of Re-Enslavement and the Law of “Slavery” Under the Regime of Jean-Louis Ferrand in Santo Domingo, 1804-1809

New West Indian Guide Vol. 86, no. 1-2 (2012), pp. 5-28 URL: http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/nwig/index URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-101725 Copyright: content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License ISSN: 0028-9930 GRAHAM NESSLER “THE SHAME OF THE NATION”: THE FORCE OF RE-ENSLAVEMENT AND THE LAW OF “SLAVERy” UNDER THE REGIME OF JEAN-LOUIS FERRAND IN SANTO DOMINGO, 1804-1809 On October 10, 1802, the French General François Kerverseau composed a frantic “proclamation” that detailed the plight of “several black and colored children” from the French ship Le Berceau who “had been disembarked” in Santo Domingo (modern Dominican Republic).1 According to the “alarms” and “foolish speculations” of various rumor-mongers in that colony, these children had been sold into slavery with the complicity of Kerverseau.2 As Napoleon’s chief representative in Santo Domingo, Kerverseau strove to dis- pel the “sinister noises” and “Vain fears” that had implicated him in such atrocities, insisting that “no sale [of these people] has been authorized” and that any future sale of this nature would result in the swift replacement of any “public officer” who authorized it. Kerverseau concluded by imploring his fellow “Citizens” to “distrust those who incessantly spread” these rumors and instead to “trust those who are charged with your safety; who guard over 1. In this era the term “Santo Domingo” referred to both the Spanish colony that later became the Dominican Republic and to this colony’s capital city which still bears this name. In this article I will use this term to refer only to the entire colony unless otherwise indicated. -

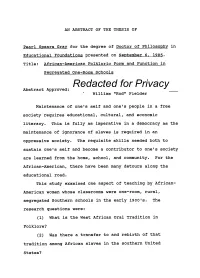

African-American Folkloric Form and Function in Segregated One-Room Schools Redacted for Privacy Abstract Approved: William "Rod" Fielder

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Pearl Spears Gray for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Foundations presented on September 6, 1985. Title: African-American Folkloric Form and Function in Segregated One-Room Schools Redacted for Privacy Abstract Approved: William "Rod" Fielder Maintenance of one's self and one's people in a free society requires educational, cultural, and economic literacy. This is fully as imperative in a democracy as the maintenance of ignorance of slaves is required in an oppressive society. The requisite skills needed both to sustain one's self and become a contributor to one's society are learned from the home, school, and community. For the African-American, there have been many detours along the educational road. This study examined one aspect of teaching by African- American women whose classrooms were one-room, rural, segregated Southern schools in the early 1900's. The research questions were: (1) What is the West African Oral Tradition in Folklore? (2) Was there a transfer to and rebirth of that tradition among African slaves in the southern United States? (3) Were there any educational applications of a West African derived folkloric oral tradition by African-American female teachers in one-room, segregated schools in the rural South? The ethnographic research technique was used because it enabled the researcher to take a culture oriented approach based in anthropology. The informants were interviewed using an open-ended question format. Other sources were archival materials, newspapers, periodicals, books, records, and telephone contacts. This research was undertaken because of a personal interest by the researcher and the literature was devoid of any previous studies making the link between a West African Oral Tradition in Folklore, and African-American women teachers in rural, one-room, segregated Southern schools. -

The House of Yisrael Cincinnati: How Normalized Institutional Violence Can Produce a Culture of Unorthodox Resistance 1963 to 2021

THE HOUSE OF YISRAEL CINCINNATI: HOW NORMALIZED INSTITUTIONAL VIOLENCE CAN PRODUCE A CULTURE OF UNORTHODOX RESISTANCE 1963 TO 2021 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Humanities by SABYL M. WILLIS B.A., Central State University, 2014 2021 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES July 27, 2021 I HERBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Sabyl M. Willis ENTITLED The House of Yisrael Cincinnati: How Normalized Institutionalized Violence Can Produce a Culture of Unorthodox Resistance BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Humanities. Awad Halabi, Ph.D. Thesis Director Valerie Stoker, Ph.D. Director, Master of Humanities Program Committee on Final Examination: Awad Halabi, Ph.D. Marlese Durr, Ph.D. Okia Opolot, Ph.D. Barry Milligan, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Academic Affairs Dean of the Graduate School ABSTRACT Willis, Sabyl M. M. Hum, Department of Humanities, Wright State University, 2021. The House of Yisrael Cincinnati: How Normalized Institutional Violence Can Produce a Culture of Unorthodox Resistance 1963 to 2021. This study examines the racial, socio-economic, and political factors that shaped The House of Yisrael, a Black Nationalist community in Cincinnati, Ohio. The members of this community structure their lives following the Black Hebrew Israelite ideology sharing the core beliefs that Black people are the "true" descendants of the ancient Israelites of the biblical narrative. Therefore, as Israelites, Black people should follow the Torah as a guideline for daily life. Because they are the "chosen people," God will judge those who have oppressed them. -

A Study of the Africans and African Americans on Jamestown Island and at Green Spring, 1619-1803

A Study of the Africans and African Americans on Jamestown Island and at Green Spring, 1619-1803 by Martha W. McCartney with contributions by Lorena S. Walsh data collection provided by Ywone Edwards-Ingram Andrew J. Butts Beresford Callum National Park Service | Colonial Williamsburg Foundation A Study of the Africans and African Americans on Jamestown Island and at Green Spring, 1619-1803 by Martha W. McCartney with contributions by Lorena S. Walsh data collection provided by Ywone Edwards-Ingram Andrew J. Butts Beresford Callum Prepared for: Colonial National Historical Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Cooperative Agreement CA-4000-2-1017 Prepared by: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Marley R. Brown III Principal Investigator Williamsburg, Virginia 2003 Table of Contents Page Acknowledgments ..........................................................................................................................iii Notes on Geographical and Architectural Conventions ..................................................................... v Chapter 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2. Research Design ............................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 3. Assessment of Contemporary Literature, BY LORENA S. WALSH .................................................... 5 Chapter 4. Evolution and Change: A Chronological Discussion ...................................................... -

Proquest Dissertations

THE ACCUMULATION OF CAPITAL AND THE SHIFTING CONSTRUCTION OF DIFFERENCE: EXAMINING THE RELATIONS OF COLONIALISM, POST-COLONIALISM AND NEO- COLONIALISM IN TRINIDAD By Dylan Brian Rum Kerrigan Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Anthropology Chair: William Leap ~-~ ~~vi/~ David Vine Dean of College ~{\\ Ill~\;) Date 2010 American University Washington, D. C. 20016 A~'?ER!CAN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 199 UMI Number: 3405935 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ___..Dissertation Publishing --..._ UMI 3405935 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Pro uesf ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons 'Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States' License. (To view a copy of this license visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3 .O/us/legalcode) Dylan Brian Rum Kerrigan 2010 DEDICATION For my parents and their parents. THE ACCUMULATION OF CAPITAL AND THE SHIFTING CONSTRUCTION OF DIFFERENCE: EXAMINING THE RELATIONS -

Tolle Lege: an Augustinian Journal of Philosophy and Theology Vol

Tolle Lege: An Augustinian Journal of Philosophy and Theology Vol. 2. No. 4. 2020. ISSN: 2672-5010 (Online) 2672-5002 (Print) KANU’S IGWEBUIKE AND COMMUNICATION IN NOLLYWOOD: A QUALITATIVE REVIEW Justine John Dyikuk University of Jos, Plateau State [email protected] DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.14402.61125 Abstract The current digital society has affected almost every sector of life. The Nigerian movie industry, which suffered the onslaught of colonialism, is not left out. Nollywood is tossed about by the desire to be truly African, on the one hand, and the aspiration to be at par with Hollywood and Bollywood, on the other. This qualitative review entitled “Igwebuike and Communication in Nollywood: A Qualitative Review” investigated the matter, using the Homophily Principle of communication as theoretical framework. It found undue Western influence, negative narratives and inability to explore Igwebuike as the communalistic philosophy of Igbo people in home movies. It recommended promotion of African heritage, transmission of culture and civilization, promotion of community life, decolonizing the film industry and entrenchment of a valuable digital culture as possible panacea. The study concluded that, given its place in global reckoning, Nollywood has the capacity to overtake other prominent industries in the world towards providing a classroom of entertainment and education for second generation Igbos and other Africans in the diaspora. Keywords: Communalism, Communication, Film, Igwebuike, Nollywood, Kanu Ikechukwu Anthony. Introduction Culture and communication are critical elements of the Nigerian movie industry. This is because most contents of cinematic platforms are laced with African flavour. From typical village square scenes to settings of royalty in the Igwe, Emir or Oba’s palace, the film industry in Africa is Africanised.