African-American Folkloric Form and Function in Segregated One-Room Schools Redacted for Privacy Abstract Approved: William "Rod" Fielder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

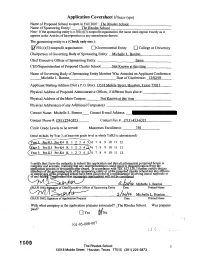

Application Coversheet (Please Type) TOGO

Application Coversheet (Please type) Name of Proposed School to open in Fall 2007: The Rhodes School Name of Sponsoring Entity: The Rhodes School Note: If the sponsoring entity is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, the name must appear exactly as it appears in the Articles of Incorporation or any amendments thereto. The sponsoring entity is a (Check only one.): 5fl501(c)(3) nonprofit organization [U Governmental Entity Q College or University Chairperson of Governing Body of Sponsoring Entity: Michelle L. Bonton Chief Executive Officer of Sponsoring Entity: Same CEO/Superintendent of Proposed Charter School: Not Known at this time Name of Governing Body of Sponsoring Entity Member Who Attended an Applicant Conference: Michelle L. Bonton Date of Conference: 12/02/05 Applicant Mailing Address (Not a P.O. Box): 13518 Mobile Street. Houston. Texas 77015 Physical Address of Proposed Administrative Offices, if different from above: Physical Address of the Main Campus: Not Known at this time Physical Address(es) of any Additional Campus(es): Contact Name: Michelle L. Bonton Contact E-mail Address: Contact Phone #: (281)224-5873 Contact Fax #: (713)453-6321 Circle Grade Levels to be served: Maximum Enrollment: _ 750 (must include, by Year 3, at least one grade level in which TAKS is administered) K 1 J34~5> 78 9 10 11 12 Pre-K4 l^LJJLJ6 7 8 9 10 H 12 (/Year 3: Pre-K3 j^e-Kj^K 1 2 3 4_J^6 7 8 9 10 11 12 I certify that I have the authority to submit this application and that all information contained herein is complete and accurate, realizing that any misrepresentation could result in disqualification from the ' " rion after award. -

The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2012 I'm Really Just an American: The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness Shea Aisha Winsett College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Winsett, Shea Aisha, "I'm Really Just an American: The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness" (2012). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626687. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-tesy-ns27 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I’m Really Just An American: The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness Shea Aisha Winsett Hyattsville, Maryland Bachelors of Arts, Oberlin College, 2008 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department -

November 1983

VOL. 7, NO. 11 CONTENTS Cover Photo by Lewis Lee FEATURES PHIL COLLINS Don't let Phil Collins' recent success as a singer fool you—he wants everyone to know that he's still as interested as ever in being a drummer. Here, he discusses the percussive side of his life, including his involvement with Genesis, his work with Robert Plant, and his dual drumming with Chester Thompson. by Susan Alexander 8 NDUGU LEON CHANCLER As a drummer, Ndugu has worked with such artists and groups as Herbie Hancock, Michael Jackson, and Weather Report. As a producer, his credits include Santana, Flora Purim, and George Duke. As articulate as he is talented, Ndugu describes his life, his drumming, and his musical philosophies. 14 by Robin Tolleson INSIDE SABIAN by Chip Stern 18 JOE LABARBERA Joe LaBarbera is a versatile drummer whose career spans a broad spectrum of experience ranging from performing with pianist Bill Evans to most recently appearing with Tony Bennett. In this interview, LaBarbera discusses his early life as a member of a musical family and the influences that have made him a "lyrical" drummer. This accomplished musician also describes the personal standards that have allowed him to maintain a stable life-style while pursuing a career as a jazz musician. 24 by Katherine Alleyne & Judith Sullivan Mclntosh STRICTLY TECHNIQUE UP AND COMING COLUMNS Double Paradiddles Around the Def Leppard's Rick Allen Drumset 56 EDUCATION by Philip Bashe by Stanley Ellis 102 ON THE MOVE ROCK PERSPECTIVES LISTENER'S GUIDE Thunder Child 60 A Beat Study by Paul T. -

ED439719.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 439 719 IR 057 813 AUTHOR McCleary, Linda C., Ed. TITLE Read from Sea to Shining Sea. Arizona Reading Program. Program Manual. INSTITUTION Arizona Humanities Council, Phoenix.; Arizona State Dept. of Library, Archives and Public Records, Phoenix. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 414p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cooperative Programs; Games; Learning Activities; *Library Planning; Library Services; *Reading Motivation; *Reading Programs; State Programs; Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS *Arizona ABSTRACT This year is the first for the collaborative effort between the Arizona Department of Library, Archives and Public Records, and Arizona Humanities Council and the members of the Arizona Reads Committee. This Arizona Reading Program manual contains information on program planning and development, along with crafts, activity sheets, fingerplays, songs, games and puzzles, and bibliographies grouped in age specific sections for preschool children through young adults, including a section for those with special needs. The manual is divided into the following sections: Introductory Materials; Goals, Objectives and Evaluation; Getting Started; Common Program Structures; Planning Timeline; Publicity and Promotion; Awards and Incentives; Parents/Family Involvement; Programs for Preschoolers; Programs for School Age Children; Programs for Young Adults; Special Needs; Selected Bibliography; Resources; Resource People; and Miscellaneous materials.(AEF) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. rn C21 Read from Sea to Shining Sea Arizona Reading Program Program Manual By Linda C. McCleary, Ed. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND Office of Educational Research and Improvement DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION BEEN GRANTED BY CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization Ann-Mary Johnson originating it. -

FACING the CHANGE CANADA and the INTERNATIONAL DECADE for PEOPLE of AFRICAN DESCENT Special Edition in Partnership with the Canadian Commission for UNESCO

PART 1 FACING THE CHANGE CANADA AND THE INTERNATIONAL DECADE FOR PEOPLE OF AFRICAN DESCENT Special Edition in Partnership with the Canadian Commission for UNESCO VOLUME 16 | NO. 3 | 2019 YEMAYA Komi Olaf SANKOFA EAGLE CLAN Komi Olaf PART ONE “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced” – James Baldwin INTRODUCTION FACING THE FINDINGS Towards Recognition, Justice and Development People of African Descent in Canada: 3 Mireille Apollon 32 A Diversity of Origins and Identities Jean-Pierre Corbeil and Hélène Maheux Overview of the Issue 5 Miriam Taylor Inflection Point – Assessing Progress on Racial Health Inequities in Canada During the Decade for 36 People of African Descent FACING THE CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES Tari Ajadi OF THE INTERNATIONAL DECADE What the African American Diaspora can Teach Us A Decade to Eradicate Discrimination and the 39 about Vernacular Black English Scourge of Racism: National Black Canadians Dr. Shana Poplack 9 Summits Take on the Legacy of Slavery The Right Honourable Michaëlle Jean THE FACE OF LIVED EXPERIENCE Unique Opportunities and Responsibilities 13 of the International Decade The Black Experience in the Greater Toronto Area The Honourable Dr. Jean Augustine 46 Dr. Wendy Cukier, Dr Mohamed Elmi and Erica Wright Count Us In: Nova Scotia’s Action Plan in Response Challenging Racism Through Asset Mapping and to the International Decade for People of African Case Study Approaches: An Example from the 16 Descent, 2015-2024 49 African Descent Communities in Vancouver, BC Wayn Hamilton Rebecca Aiyesa and Dr. Oleksander (Sasha) Kondrashov Migration, Identity and Oppression: An Inter-provincial Community Initiative Exploring FACING THE LEGACY OF COLONIALISM and Addressing the Intersectionality of Oppression and Related Health, Social and Economic Costs The Sun Never Sets, The Sun Waits to Rise: 53 The Enduring Structural Legacies of European Dr. -

HS, African American History, Quarter 1

2021-2022, HS, African American History, Quarter 1 Students begin a comprehensive study of African American history from pre1619 to present day. The course complies T.C.A. § 49-6-1006 on inclusion of Black history and culture. Historical documents are embedded in the course in compliance with T.C.A. § 49-6-1011. The Beginnings of Slavery and the Slave Trade - pre-1619 State Standards Test Knowledge Suggested Learning Suggested Pacing AAH.01 Analyze the economic, The economic, political, and Analyze and discuss reasons for political, and social reasons for social reasons for colonization the focusing the slave trade on focusing the slave trade on and why the slave trade focused Africa, especially the natural Africa, including the roles of: on Africans. resources, labor shortages, and Africans, Europeans, and religion. 1 Week Introduction The role Africans, Europeans, and colonists. colonist played in the slave trade. Analyze the motivations of Africans, Europeans, and colonists to participate in slave trading. AAH.02 Analyze the role of The geography of Africa including Analyze various maps of Africa geography on the growth and the Sahara, Sahel, Ethiopian including trade routes, physical development of slavery. Highlands, the savanna (e.g., geography, major tribal location, Serengeti), rainforest, African and natural resources. Great Lakes, Atlantic Ocean, Use Exploring Africa Website to Mediterranean Sea, and Indian understand previous uses of Ocean. 1 Week slavery and compare to European Deep Dive into The impact of Africa’s geography slave trade. African Geography on the development of slavery. Compare the practice of slavery Identify the Igbo people. between the internal African slave trade, slave trade in Europe Comparisions of the Trans- during the Middle Ages, the Saharan vs Trans-Atlantic. -

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm. -

How Did Forced Migration and Forced Displacement Change Igbo Women’S and Their African American Daughters’ Environmental Identity?

How Did Forced Migration and Forced Displacement Change Igbo Women’s and Their African American Daughters’ Environmental Identity? A THESIS Presented to the Urban Sustainability Department Antioch University, Los Angeles In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Urban Sustainability Capstone Committee Members: Susan Gentile, MS. Jane Paul, MA. Susan Clayton, Ph.D. Submitted by Jamila K. Gaskins April 2018 Abstract Environmental identity and forced migration are well-researched subjects, yet, the intergenerational effects of forced migration on environmental identity lack substantive examination. This paper explores and adds to that research by asking the question, how did forced migration and forced displacement change Igbo women’s and their African American daughter's environmental identity? The Igbo women were kidnapped from Igboland (modern-day Nigeria) for sale in the transatlantic slave trade. A significant percentage of the Igbo women shipped to colonial America were taken to the Chesapeake colonies. Historians indicate that Igbo women were important in the birth of a new generation of African Americans due to the high number of their children surviving childbirth. One facet of environmental identity is place identity, which can be an indicator of belonging. This paper investigates the creation of belonging in the midst of continued, generational disruption in the relationship to the land, or environmental identity. Historical research and an extensive literature review were the research methods. It was concluded that stating a historical environmental identity with any scientific validity is not possible. Instead, there is a reason to suggest a high level of connection between cultural identity and the environmental identity of the Igbo before colonization and enslavement by colonial Americans. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

African Names and Naming Practices: the Impact Slavery and European

African Names and Naming Practices: The Impact Slavery and European Domination had on the African Psyche, Identity and Protest THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Liseli A. Fitzpatrick, B.A. Graduate Program in African American and African Studies The Ohio State University 2012 Thesis Committee: Lupenga Mphande, Advisor Leslie Alexander Judson Jeffries Copyrighted by Liseli Anne Maria-Teresa Fitzpatrick 2012 Abstract This study on African naming practices during slavery and its aftermath examines the centrality of names and naming in creating, suppressing, retaining and reclaiming African identity and memory. Based on recent scholarly studies, it is clear that several elements of African cultural practices have survived the oppressive onslaught of slavery and European domination. However, most historical inquiries that explore African culture in the Americas have tended to focus largely on retentions that pertain to cultural forms such as religion, dance, dress, music, food, and language leaving out, perhaps, equally important aspects of cultural retentions in the African Diaspora, such as naming practices and their psychological significance. In this study, I investigate African names and naming practices on the African continent, the United States and the Caribbean, not merely as elements of cultural retention, but also as forms of resistance – and their importance to the construction of identity and memory for persons of African descent. As such, this study examines how European colonizers attacked and defiled African names and naming systems to suppress and erase African identity – since names not only aid in the construction of identity, but also concretize a people’s collective memory by recording the circumstances of their experiences. -

Travel the Usa: a Reading Roadtrip Booklist

READING ROADTRIP USA TRAVEL THE USA: A READING ROADTRIP BOOKLIST Prepared by Maureen Roberts Enoch Pratt Free Library ALABAMA Giovanni, Nikki. Rosa. New York: Henry Holt, 2005. This title describes the story of Alabama native Rosa Parks and her courageous act of defiance. (Ages 5+) Johnson, Angela. Bird. New York: Dial Books, 2004. Devastated by the loss of a second father, thirteen-year-old Bird follows her stepfather from Cleveland to Alabama in hopes of convincing him to come home, and along the way helps two boys cope with their difficulties. (10-13) Hamilton, Virginia. When Birds Could Talk and Bats Could Sing: the Adventures of Bruh Sparrow, Sis Wren and Their Friends. New York: Blue Sky Press, 1996. A collection of stories, featuring sparrows, jays, buzzards, and bats, based on African American tales originally written down by Martha Young on her father's plantation in Alabama after the Civil War. (7-10) McKissack, Patricia. Run Away Home. New York: Scholastic, 1997. In 1886 in Alabama, an eleven-year-old African American girl and her family befriend and give refuge to a runaway Apache boy. (9-12) Mandel, Peter. Say Hey!: a Song of Willie Mays. New York: Hyperion Books for Young Children, 2000. Rhyming text tells the story of Willie Mays, from his childhood in Alabama to his triumphs in baseball and his acquisition of the nickname the "Say Hey Kid." (4-8) Ray, Delia. Singing Hands. New York: Clarion Books, 2006. In the late 1940s, twelve-year-old Gussie, a minister's daughter, learns the definition of integrity while helping with a celebration at the Alabama School for the Deaf--her punishment for misdeeds against her deaf parents and their boarders. -

State of the World's Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2016 (MRG)

State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2016 Events of 2015 Focus on culture and heritage State of theWorld’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 20161 Events of 2015 Front cover: Cholitas, indigenous Bolivian Focus on culture and heritage women, dancing on the streets of La Paz as part of a fiesta celebrating Mother’s Day. REUTERS/ David Mercado. Inside front cover: Street theatre performance in the Dominican Republic. From 2013 to 2016 MRG ran a street theatre programme to challenge discrimination against Dominicans of Haitian Descent in the Acknowledgements Dominican Republic. MUDHA. Minority Rights Group International (MRG) Inside back cover: Maasai community members in gratefully acknowledges the support of all Kenya. MRG. organizations and individuals who gave financial and other assistance to this publication, including the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. © Minority Rights Group International, July 2016. All rights reserved. Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non-commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for Support our work commercial purposes without the prior express Donate at www.minorityrights.org/donate permission of the copyright holders. MRG relies on the generous support of institutions and individuals to help us secure the rights of For further information please contact MRG. A CIP minorities and indigenous peoples around the catalogue record of this publication is available from world. All donations received contribute directly to the British Library. our projects with minorities and indigenous peoples. ISBN 978-1-907919-80-0 Subscribe to our publications at State of www.minorityrights.org/publications Published: July 2016 Another valuable way to support us is to subscribe Lead reviewer: Carl Soderbergh to our publications, which offer a compelling Production: Jasmin Qureshi analysis of minority and indigenous issues and theWorld’s Copy editing: Sophie Richmond original research.