THE FINAL Slave Diet Site Bulletin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frederick Douglass

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection AMERICAN CRISIS BIOGRAPHIES Edited by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Ph. D. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Zbe Hmcrican Crisis Biographies Edited by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Ph.D. With the counsel and advice of Professor John B. McMaster, of the University of Pennsylvania. Each I2mo, cloth, with frontispiece portrait. Price $1.25 net; by mail» $i-37- These biographies will constitute a complete and comprehensive history of the great American sectional struggle in the form of readable and authoritative biography. The editor has enlisted the co-operation of many competent writers, as will be noted from the list given below. An interesting feature of the undertaking is that the series is to be im- partial, Southern writers having been assigned to Southern subjects and Northern writers to Northern subjects, but all will belong to the younger generation of writers, thus assuring freedom from any suspicion of war- time prejudice. The Civil War will not be treated as a rebellion, but as the great event in the history of our nation, which, after forty years, it is now clearly recognized to have been. Now ready: Abraham Lincoln. By ELLIS PAXSON OBERHOLTZER. Thomas H. Benton. By JOSEPH M. ROGERS. David G. Farragut. By JOHN R. SPEARS. William T. Sherman. By EDWARD ROBINS. Frederick Douglass. By BOOKER T. WASHINGTON. Judah P. Benjamin. By FIERCE BUTLER. In preparation: John C. Calhoun. By GAILLARD HUNT. Daniel Webster. By PROF. C. H. VAN TYNE. Alexander H. Stephens. BY LOUIS PENDLETON. John Quincy Adams. -

The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2006 Dismantling the Master’s Schoolhouse: The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction Miya G. Abbot University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Abbot, Miya G., "Dismantling the Master’s Schoolhouse: The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2006. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1487 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Miya G. Abbot entitled "Dismantling the Master’s Schoolhouse: The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of , with a major in English. Miriam Thaggert, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mary Jo Reiff, Janet Atwill Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Miya G. -

Greens, Beans & Groundnuts African American Foodways

Greens, Beans & Groundnuts African American Foodways City of Bowie Museums Belair Mansion 12207 Tulip Grove Drive Bowie MD 20715 301-809-3089Email: [email protected]/museum Greens, Beans & Groundnuts -African American Foodways Belair Mansion City of Bowie Museums Background: From 1619 until 1807 (when the U.S. Constitution banned the further IMPORTATION of slaves), many Africans arrived on the shores of a new and strange country – the American colonies. They did not come to the colonies by their own choice. They were slaves, captured in their native land (Africa) and brought across the ocean to a very different place than what they knew at home. Often, slaves worked as cooks in the homes of their owners. The food they had prepared and eaten in Africa was different from food eaten by most colonists. But, many of the things that Africans were used to eating at home quickly became a part of what American colonists ate in their homes. Many of those foods are what we call “soul food,” and foods are still part of our diverse American culture today. Food From Africa: Most of the slaves who came to Maryland and Virginia came from the West Coast of Africa. Ghana, Gambia, Nigeria, Togo, Mali, Sierra Leone, Benin, Senegal, Guinea, the Ivory Coast are the countries of West Africa. Foods consumed in the Western part of Africa were (and still are) very starchy, like rice and yams. Rice grew well on the western coast of Africa because of frequent rain. Rice actually grows in water. Other important foods were cassava (a root vegetable similar to a potato), plantains (which look like bananas but are not as sweet) and a wide assortment of beans. -

The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2012 I'm Really Just an American: The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness Shea Aisha Winsett College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Winsett, Shea Aisha, "I'm Really Just an American: The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness" (2012). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626687. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-tesy-ns27 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I’m Really Just An American: The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness Shea Aisha Winsett Hyattsville, Maryland Bachelors of Arts, Oberlin College, 2008 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department -

The Thirteenth Amendment: Modern Slavery, Capitalism, and Mass Incarceration Michele Goodwin University of California, Irvine

Cornell Law Review Volume 104 Article 4 Issue 4 May 2019 The Thirteenth Amendment: Modern Slavery, Capitalism, and Mass Incarceration Michele Goodwin University of California, Irvine Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Michele Goodwin, The Thirteenth Amendment: Modern Slavery, Capitalism, and Mass Incarceration, 104 Cornell L. Rev. 899 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol104/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT: MODERN SLAVERY, CAPITALISM, AND MASS INCARCERATION Michele Goodwint INTRODUCTION ........................................ 900 I. A PRODIGIOUS CYCLE: PRESERVING THE PAST THROUGH THE PRESENT ................................... 909 II. PRESERVATION THROUGH TRANSFORMATION: POLICING, SLAVERY, AND EMANCIPATION........................ 922 A. Conditioned Abolition ....................... 923 B. The Punishment Clause: Slavery's Preservation Through Transformation..................... 928 C. Re-appropriation and Transformation of Black Labor Through Black Codes, Crop Liens, Lifetime Labor, Debt Peonage, and Jim Crow.. 933 1. Black Codes .......................... 935 2. Convict Leasing ........................ 941 -

RIVERFRONT CIRCULATING MATERIALS (Can Be Checked Out)

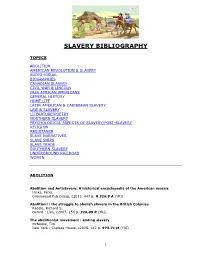

SLAVERY BIBLIOGRAPHY TOPICS ABOLITION AMERICAN REVOLUTION & SLAVERY AUDIO-VISUAL BIOGRAPHIES CANADIAN SLAVERY CIVIL WAR & LINCOLN FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS GENERAL HISTORY HOME LIFE LATIN AMERICAN & CARIBBEAN SLAVERY LAW & SLAVERY LITERATURE/POETRY NORTHERN SLAVERY PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF SLAVERY/POST-SLAVERY RELIGION RESISTANCE SLAVE NARRATIVES SLAVE SHIPS SLAVE TRADE SOUTHERN SLAVERY UNDERGROUND RAILROAD WOMEN ABOLITION Abolition and Antislavery: A historical encyclopedia of the American mosaic Hinks, Peter. Greenwood Pub Group, c2015. 447 p. R 326.8 A (YRI) Abolition! : the struggle to abolish slavery in the British Colonies Reddie, Richard S. Oxford : Lion, c2007. 254 p. 326.09 R (YRI) The abolitionist movement : ending slavery McNeese, Tim. New York : Chelsea House, c2008. 142 p. 973.71 M (YRI) 1 The abolitionist legacy: from Reconstruction to the NAACP McPherson, James M. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, c1975. 438 p. 322.44 M (YRI) All on fire : William Lloyd Garrison and the abolition of slavery Mayer, Henry, 1941- New York : St. Martin's Press, c1998. 707 p. B GARRISON (YWI) Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the heroic campaign to end slavery Metaxas, Eric New York, NY : Harper, c2007. 281p. B WILBERFORCE (YRI, YWI) American to the backbone : the life of James W.C. Pennington, the fugitive slave who became one of the first black abolitionists Webber, Christopher. New York : Pegasus Books, c2011. 493 p. B PENNINGTON (YRI) The Amistad slave revolt and American abolition. Zeinert, Karen. North Haven, CT : Linnet Books, c1997. 101p. 326.09 Z (YRI, YWI) Angelina Grimke : voice of abolition. Todras, Ellen H., 1947- North Haven, Conn. : Linnet Books, c1999. 178p. YA B GRIMKE (YWI) The antislavery movement Rogers, James T. -

The Gradual Loss of African Indigenous Vegetables in Tropical America: a Review

The Gradual Loss of African Indigenous Vegetables in Tropical America: A Review 1 ,2 INA VANDEBROEK AND ROBERT VOEKS* 1The New York Botanical Garden, Institute of Economic Botany, 2900 Southern Boulevard, The Bronx, NY 10458, USA 2Department of Geography & the Environment, California State University—Fullerton, 800 N. State College Blvd., Fullerton, CA 92832, USA *Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected] Leaf vegetables and other edible greens are a crucial component of traditional diets in sub-Saharan Africa, used popularly in soups, sauces, and stews. In this review, we trace the trajectories of 12 prominent African indigenous vegetables (AIVs) in tropical America, in order to better understand the diffusion of their culinary and ethnobotanical uses by the African diaspora. The 12 AIVs were selected from African reference works and preliminary reports of their presence in the Americas. Given the importance of each of these vegetables in African diets, our working hypothesis was that the culinary traditions associated with these species would be continued in tropical America by Afro-descendant communities. However, a review of the historical and contemporary literature, and consultation with scholars, shows that the culinary uses of most of these vegetables have been gradually lost. Two noteworthy exceptions include okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) and callaloo (Amaranthus viridis), although the latter is not the species used in Africa and callaloo has only risen to prominence in Jamaica since the 1960s. Nine of the 12 AIVs found refuge in the African- derived religions Candomblé and Santería, where they remain ritually important. In speculating why these AIVs did not survive in the diets of the New World African diaspora, one has to contemplate the sociocultural, economic, and environmental forces that have shaped—and continue to shape—these foodways and cuisines since the Atlantic slave trade. -

FACING the CHANGE CANADA and the INTERNATIONAL DECADE for PEOPLE of AFRICAN DESCENT Special Edition in Partnership with the Canadian Commission for UNESCO

PART 1 FACING THE CHANGE CANADA AND THE INTERNATIONAL DECADE FOR PEOPLE OF AFRICAN DESCENT Special Edition in Partnership with the Canadian Commission for UNESCO VOLUME 16 | NO. 3 | 2019 YEMAYA Komi Olaf SANKOFA EAGLE CLAN Komi Olaf PART ONE “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced” – James Baldwin INTRODUCTION FACING THE FINDINGS Towards Recognition, Justice and Development People of African Descent in Canada: 3 Mireille Apollon 32 A Diversity of Origins and Identities Jean-Pierre Corbeil and Hélène Maheux Overview of the Issue 5 Miriam Taylor Inflection Point – Assessing Progress on Racial Health Inequities in Canada During the Decade for 36 People of African Descent FACING THE CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES Tari Ajadi OF THE INTERNATIONAL DECADE What the African American Diaspora can Teach Us A Decade to Eradicate Discrimination and the 39 about Vernacular Black English Scourge of Racism: National Black Canadians Dr. Shana Poplack 9 Summits Take on the Legacy of Slavery The Right Honourable Michaëlle Jean THE FACE OF LIVED EXPERIENCE Unique Opportunities and Responsibilities 13 of the International Decade The Black Experience in the Greater Toronto Area The Honourable Dr. Jean Augustine 46 Dr. Wendy Cukier, Dr Mohamed Elmi and Erica Wright Count Us In: Nova Scotia’s Action Plan in Response Challenging Racism Through Asset Mapping and to the International Decade for People of African Case Study Approaches: An Example from the 16 Descent, 2015-2024 49 African Descent Communities in Vancouver, BC Wayn Hamilton Rebecca Aiyesa and Dr. Oleksander (Sasha) Kondrashov Migration, Identity and Oppression: An Inter-provincial Community Initiative Exploring FACING THE LEGACY OF COLONIALISM and Addressing the Intersectionality of Oppression and Related Health, Social and Economic Costs The Sun Never Sets, The Sun Waits to Rise: 53 The Enduring Structural Legacies of European Dr. -

An Experience in African Cuisine

AFRICAN FOOD SAFARI I will not provide you with hundreds of recipes I will introduce you to two or AN EXPERINCE IN three common to the regions of Nigeria, AFRICAN CUISINE Sudan, Ghana, Mali, Niger, Chad, Ivory Coast, Cameroon and surrounding Before you obtain your visa, buy and areas of the central part of Africa. pack your sun hat, Danhiki or Neru shirts, safari shorts, sunglasses, I will not spend time in this book on sunscreen, sun dresses and mosquito dishes that reflect Egypt, Morocco, nets, etc., I suggest that to you: Libya and Algeria due to the fact that these parts of North and North East Prepare yourself not only mentally, Africa are familiar with Mediterranean but physically as well, because the and Arabian based foods. most important thing that you have to internalize is that the type of food and For example, should you be in Angola, its preparation is: a little bit, somewhat there is a prevalence of Portuguese different, and most significantly, very, food. very different from what you are In Kenya, Tanzania and Somalia there accustomed to. is a drift into the East Indian Cuisine. South Africa drifts into the English Be prepared for this fact: None of the cuisine and The Congo, Belgium following foods are on the menu during cuisine. our safari: There is no cannelloni, tortellini, tamales, tortillas empanadas, Take your camera with you and let masala, rotis, shrimp fried rice or us go on a Safari. Don’t worry about samosas! Not even feta cheese! the lions, elephants, giraffes, hippos, cheetahs and rhinos. -

HEALING the SCARS of SLAVERY: REFLECTIONS in 18Th CENTURY LITERATURE and BEYOND

HEALING THE SCARS OF SLAVERY: REFLECTIONS IN 18th CENTURY LITERATURE AND BEYOND DR. SANGITA GHODKE PDEA's Baburaoji Gholap College, Sangvi, Pune. India The main theme of the present paper is the socio-economic, religious and psychosomatic encounters in the literature written about the Slaves and the Oppressed. The paper is an attempt to explore psychosomatic and socio-economic consequences of the forced slave trade of eighteenth century through literature of the sufferers of Africa and America. Eighteenth century has been condemned for the scars and stigma of full-fledged slave trade. The European nations and the American States were the dominant players of the cruel inhuman but commercially motivated slave trade and socially and economically weak populace from the continents like Africa were the tragic sufferers. The present paper is divided into four parts: (i) origins of slavery, (ii) slave trade and its religious implications in Africa and America, (iii) the survey of the slave narratives with illustrations of healing the scars of slavery from Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin and (iv) present day scenario of neo slavery. The paper attempts to elaborate socio-economic and religious interests of the masters and psychosomatic problems of the slaves of the eighteenth century. All the philosophers and social reformers have guided the humanity by being virtuous. The concluding part will try to highlight guiding principle and spiritual path of enlightenment shown by Mahatma Gandhi from India, Martin Luther King Junior from the USA, Nelson Mandela from South Africa and Dalai Lama from Tibet by becoming non-violent and righteous. -

HS, African American History, Quarter 1

2021-2022, HS, African American History, Quarter 1 Students begin a comprehensive study of African American history from pre1619 to present day. The course complies T.C.A. § 49-6-1006 on inclusion of Black history and culture. Historical documents are embedded in the course in compliance with T.C.A. § 49-6-1011. The Beginnings of Slavery and the Slave Trade - pre-1619 State Standards Test Knowledge Suggested Learning Suggested Pacing AAH.01 Analyze the economic, The economic, political, and Analyze and discuss reasons for political, and social reasons for social reasons for colonization the focusing the slave trade on focusing the slave trade on and why the slave trade focused Africa, especially the natural Africa, including the roles of: on Africans. resources, labor shortages, and Africans, Europeans, and religion. 1 Week Introduction The role Africans, Europeans, and colonists. colonist played in the slave trade. Analyze the motivations of Africans, Europeans, and colonists to participate in slave trading. AAH.02 Analyze the role of The geography of Africa including Analyze various maps of Africa geography on the growth and the Sahara, Sahel, Ethiopian including trade routes, physical development of slavery. Highlands, the savanna (e.g., geography, major tribal location, Serengeti), rainforest, African and natural resources. Great Lakes, Atlantic Ocean, Use Exploring Africa Website to Mediterranean Sea, and Indian understand previous uses of Ocean. 1 Week slavery and compare to European Deep Dive into The impact of Africa’s geography slave trade. African Geography on the development of slavery. Compare the practice of slavery Identify the Igbo people. between the internal African slave trade, slave trade in Europe Comparisions of the Trans- during the Middle Ages, the Saharan vs Trans-Atlantic. -

The Australasian Review of African Studies African Studies Association

The Australasian Review of African Studies African Studies Association of Australasia and the Pacific Volume 32 Number 1 June 2011 CONTENTS Tribute to Horst Ulrich Beier, 1922-2011 3 Donald Denoon Call for papers AFSAAP 34th Annual Conference 5 AFSAAP and the Benin Bronze - Building Bridges? 6 Tanya Lyons – ARAS Editor Articles The Nubians of Kenya and the Emancipatory Potential of 12 Collective Recognition Samantha Balaton-Chrimes Policy and Governance Issues in Kenya’s Border Towns: The 32 case of Wajir groundwater management. Abdi Dahir Osman, Vivian Lin, Priscilla Robinson, and Darryl Jackson Conserving exploitation? A political ecology of forestry policy in 59 Sierra Leone Paul G. Munro and Greg Hiemstra-van der Horst Oil, Environment and Resistance in Tanure Ojaide’s The Tale 79 of the Harmattan Ogaga Okuyade Looking beyond the Benin Bronze Head: Provisional Notes on 99 Culture, Nation, and Cosmopolitanism Kudzai Matereke The Badcock Collection from the Upper Congo 119 Barry Craig ARAS Vol.32 No.1 June 2011 1 Member Profile – Peter Run, AFSAAP Secretary 148 Community Engagement: Pigs, Politics, Africa 149 Book Reviews Emma Christopher, A Merciless Place: The Lost Story of 152 Britain's Convict Disaster in Africa and How it Led to the Settlement of Australia. Paul Munro Peter McCann. Stirring the Pot A History of African Cuisine 154 Graeme Counsel Francis Mading Deng. Sudan at the Brink: Self-Determination 156 and National Unity. Peter Run AFSAAP President’s Report June 2011 158 Postgraduate Workshop AFSAAP 2011 Annual Conference 160 The AFSAAP Postgraduate Essay Prize 2011 162 The AFSAAP Postgraduate Essay Guidelines and Procedures 163 ARAS Guidelines for Contributors 165 About AFSAAP 166 2 ARAS Vol.32 No.