A Study on Fawlty Towers and National Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

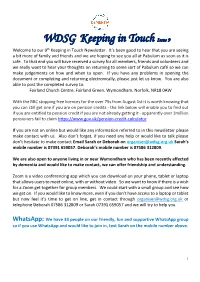

WDSG Keeping in Touch Newsletter, Issue 9

WDSG Keeping in Touch Issue 9 Welcome to our 9th Keeping in Touch Newsletter. It’s been good to hear that you are seeing a bit more of family and friends and we are hoping to see you all at Pabulum as soon as it is safe. To that end you will have received a survey for all members, friends and volunteers and we really want to hear your thoughts on returning to some sort of Pabulum café so we can make judgements on how and when to open. If you have any problems in opening the document or completing and returning electronically, please just let us know. You are also able to post the completed survey to: Fairland Church Centre, Fairland Green, Wymondham, Norfolk, NR18 0AW With the BBC stopping free licences for the over 75s from August 1st it is worth knowing that you can still get one if you are on pension credits - the link below will enable you to find out if you are entitled to pension credit if you are not already getting it - apparently over 1million pensioners fail to claim https://www.gov.uk/pension-credit-calculator If you are not on online but would like any information referred to in this newsletter please make contact with us. Also don’t forget, if you need any help or would like to talk please don’t hesitate to make contact Email Sarah or Deborah on [email protected] Sarah’s mobile number is 07391 659057. Deborah’s mobile number is 07586 312809. We are also open to anyone living in or near Wymondham who has been recently affected by dementia and would like to make contact, we can offer friendship and understanding. -

Savoring the Classical Tradition in Drama

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA MEMORABLE PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD I N P R O U D COLLABORATION WIT H THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE PLAYERS, NEW YORK CITY THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION JIM DALE ♦ Friday, January 24 In the 1950s and ’60s JIM DALE was known primarily as a singer and songwriter, with such hits as Oscar nominee “Georgy Girl” to his credit. Meanwhile he was earning plaudits as a film and television comic, with eleven Carry On features that made him a NATIONAL ARTS CLUB household name in Britain. Next came stage roles like 15 Gramercy Park South Autolycus and Bottom with Laurence Olivier’s National Manhattan Theatre Company, and Fagin in Cameron Mackintosh’s PROGRAM AT 6:00 P.M. Oliver. In 1980 he collected a Tony Award for his title Admission Free, But role in Barnum. Since then he has been nominated for Reservations Requested Tony, Drama Desk, and other honors for his work in such plays as Candide, Comedians, Joe Egg, Me and My Girl, and Scapino. As if those accolades were not enough, he also holds two Grammy Awards and ten Audie Awards as the “voice” of Harry Potter. We look forward to a memorable evening with one of the most versatile performers in entertainment history. RON ROSENBAUM ♦ Monday, March 23 Most widely known for Explaining Hitler, a 1998 best-seller that has been translated into ten languages, RON ROSENBAUM is also the author of The Secret Parts of Fortune, Those Who Forget the Past, and How the End Begins: The Road to a Nuclear World War III. -

Showbuzz 201307

SHOWBUZZ JULY 2013 FISHY FAWLTY FUN September 2009 Basil, Sybil, Polly, Manuel and a host of long-suffering and much abused guests are back in INSIDE THIS ISSUE: the live stage adaptation of one of the best-loved British TV comedies ever written! FISHY FAWLTY FUN P.1 Three classic episodes had the Preview audience in stitches and calling for more, as the cast revisited The Kipper and the Corpse, Wedding Party and Gourmet Night. PHANTOM AUDITIONS P.2 Incredibly, when John Cleese and Connie Booth first submitted their scripts for Fawlty Towers to the BBC they LEND ME A TENOR P.3 were not at all well received. But, after the success of Monty Python the BBC decided to trust Cleese’s WHAT’S ON P.4 judgement, and the result was one of the most treasured and influential television comedies of all time. Winter in Launnie is a whole lot funnier this week and next, and we look forward to giving you a warm welcome to the Earl Arts Centre with 12 performances running through until July 28. FAWLTY TOWERS 2 17-28 JULY Creativity TICKETS 6323 3666 theatrenorth.com.au Innovation Excellence Enquiries Jamie Hillard 0433 999 248 Belinda King 0411 233 345 PO Box 951 LAUNCESTON 7250 ETC’s Presentation Partners ETC's Awards ABN: 78 571 056 515 [email protected] H finalen t encoretheatre.org.au more SHOWBUZZ Seeing is So you want to Believing in 2013 AUDITION? Susie Heggie works as a Musical/Vocal Director and Repetiteur with Encore. She sits in on a LOT of auditions, so we asked her what she looks for when she’s on an audition panel, and she has offered the following thoughts and comments on three key areas. -

Fawlty Towers - Episode Guide

Performances October 6, 7, 8, 13, 14, 15 Three episodes of the classic TV series are brought to life on stage. Written by John Cleese & Connie Booth. Music by Dennis Wilson By Special Arrangement With Samuel French and Origin Theatrical Auditions Saturday June 18, Sunday June 19 Thurgoona Community Centre 10 Kosciuszko Road, Thurgoona NSW 2640 Director: Alex 0410 933 582 FAWLTY TOWERS - EPISODE GUIDE ACT ONE – THE GERMANS Sybil is in hospital for her ingrowing toenail. “Perhaps they'll have it mounted for me,” mutters Basil as he tries to cope during her absence. The fire-drill ends in chaos with Basil knocked out by the moose’s head in the lobby. The deranged host then encounters the Germans and tells them the “truth” about their Fatherland… ACT TWO – COMMUNICATION PROBLEMS It’s not a wise man who entrusts his furtive winnings on the horses to an absent-minded geriatric Major, but Basil was never known for that quality. Parting with those ill-gotten gains was Basil’s first mistake; his second was to tangle with the intermittently deaf Mrs Richards. ACT THREE – WALDORF SALAD Mine host's penny-pinching catches up with him as an American guest demands the quality of service not normally associated with the “Torquay Riviera”, as Basil calls his neck of the woods. A Waldorf Salad is not part of Fawlty Towers' standard culinary repertoire, nor is a Screwdriver to be found on the hotel's drinks list… FAWLTY TOWERS – THE REGULARS BASIL FAWLTY (John Cleese) The hotel manager from hell, Basil seems convinced that Fawlty Towers would be a top-rate establishment, if only he didn't have to bother with the guests. -

February 2020

TV & RADIO LISTINGS GUIDE FEBRUARY 2020 PRIMETIME For more information go to witf.org/tv WITF honors the legacy of Black History Month with special • programming including the American Masters premiere of Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool. This deep dive into the world of a beloved musical giant features a mix of never before seen footage and new interviews with Quincy Jones, Carlos Santana, Clive Davis, Wayne Shorter, Marcus Miller, Ron Carter, family members and others. The film’s producers were granted access to the Miles Davis estate providing a great depth of material to utilize in this two-hour documentary airing February 25 at 9pm. Fans of Death in Paradise rejoice! The series will continue to solve crimes on a weekly basis for several more months ahead. Season 7 wraps this month, but Season 8 returns in March. Season 9 is currently airing on BBC in the United Kingdom. The brand-new season travels across the pond and lands on the WITF schedule this summer. I had the opportu- nity to see some of the first images from SERIES MARATHON the new season and it looks like there are some changes in store! I don’t want to HOWARDS END ON MASTERPIECE give anything away, so I’ll keep it vague until we get closer to the premiere of the FEBRUARY 2 • 4–9pm new season. In the meantime, the series continues Thursdays at 9pm. Doc Martin Season 8 concludes this Do you have a Smart TV? If you do, through broadcast, cable, satellite or the month. I’m hopeful to bring you Season WITF is now also available on internet, we’re proud to be your neighbor- 9 with Martin and Louisa in early 2021. -

Patrons' Newsletter Diary

Patrons’Volume 2, Issue 7 | April 2013Newsletter May Fawlty Towers Sandy Wilson’s Written by John Cleese & Connie The Boy Friend 10 Booth Maghull Musical Theatre Company Directed by Les Gomersall By arrangement with Samuel French May 10th - 18th June 12th - 15th Box Office Opens 3rd May Box Office Opens 5th June Carousel Advance Booking on 01695 632372 Diary Birkdale Orpheus Society Coming soon to the Little Theatre Music by Richard Rodgers, book & lyrics by Oscar An Evening of Music with Old Hammerstein II May 25th - June 1st Hall Brass Sunday 16th June 2013 Box office opens 18th May 2013 Advance Booking 01942715684 Acorn Antiques: The Musical Advanced Booking on 01704 564042 Southport Spotlights Musical Theatre Company Damages Music, lyrics and script by Victoria Woods June June 29th - July 6th, Matinee July 6th Written by Stephen Thompson Loreto Bamber Dance Show Directed by Stephen Huges-Alty Box office opens 24th June 2013 4 Friday 21st - 22nd June 2013 Advanced Booking on 07927 331977 An SDC Bar/Studio Production Box Office Opens 20th June June 4th - 8th Advance Booking 01704 538351 Box Office Opens 28th May ‘Fawlty Towers’ A comedy By Les Gomersall, Director In the early 1970s John Cleese was unusual hotelier Donald Sinclair. a member of the highly success- The result of course turned out to ful Monty Python’s Flying Circus be Fawlty Towers owned and run team. In May 1971 the team were by the equally unusual, but ex- staying at the Gleneagles Hotel in tremely funny, Basil Fawlty Torquay which was owned and run Only 12 episodes were written, by a Mr Donald Sinclair. -

THIS ISSUE: Comedy

2014-2015 September ISSUE 1 scene. THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS THEATRE ASSOCIATION THIS ISSUE: Comedy www.ista.co.uk WHO’S WHO @ ISTA… CONTENTS Patron 2 Connections Professor Jonothan Neelands, by Rebecca Kohler National Teaching Fellow, Chair of Drama and Theatre Education in the Institute of Education 3 Comedy d’un jour and Chair of Creative Education in the Warwick Business School (WBS) at the University of by Francois Zanini Warwick. 4 Learning through humour Board of trustees by Mike Pasternak Iain Stirling (chair), Scotland Formerly Superintendent, Advanced Learning Schools, Riyadh. Recently retired. 8 Desperately seeking the laughs Jen Tickle (vice chair), Jamaica by Peter Michael Marino Head of Visual & Performing Arts and Theory of Knowledge at The Hillel Academy, Jamaica. 9 “Chou” – the comic actor in Chinese opera Dinos Aristidou, UK by Chris Ng Freelance writer, director, consultant. 11 Directing comedy Alan Hayes, Belgium by Sacha Kyle Theatre teacher International School Brussels. Sherri Sutton, Switzerland 12 Videotape everything, change and be Comic, director and chief examiner for IB DP Theatre. Theatre teacher at La Chataigneraie. grateful Jess Thorpe, Scotland by Dorothy Bishop Co Artistic Director of Glas(s) Performance and award winning young people’s company 13 Seriously funny Junction 25. Visiting. Lecturer in the Arts in Social Justice at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. by Stephen Finegold Honorary life members 15 How I got the best job in the world! Dinos Aristidou, UK Being a clown, being a -

4 April 2008 Page 1 of 6 SATURDAY 29 MARCH 2008 Dan Freedman and Nick Romero’S Comedy About the First Broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in May 1999

Radio 7 Listings for 29 March – 4 April 2008 Page 1 of 6 SATURDAY 29 MARCH 2008 Dan Freedman and Nick Romero’s comedy about the First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in May 1999. swashbuckling exploits of Lord Zimbabwe, occultist and SAT 13:30 The Men from the Ministry (b007jqfn) SAT 00:00 Simon Bovey - Slipstream (b009mbjn) adventurer. Not on Your Telly Fight for the Future Lord Zimbabwe ...... Nick Romero The bungling bureaucrats spark bedlam during a BBC Jurgen and Kate are desperate to get the weapon away before all Dr Lilac ...... Dan Freedman 'Panorama' probe. is lost... Cletus ...... Owen Oakeshott Stars Richard Murdoch and Deryck Guyler. Conclusion of Simon Bovey's sci-fi adventure series set during Marylou Coyotecock ...... Sophie Aldred With Norma Ronald, Ronald Baddiley and John Graham. the Second World War. Vicar ...... Colin Guthrie Written by Edward Taylor and John Graham. Stars Rory Kinnear as Jurgen Rall, Tim McMullan as Major Theremin ...... Peter Donaldson 'The Men from the Ministry' ran for 14 series between 1962 Barton, Joannah Tincey as Kate Richey, Ben Crowe as Other parts played by the cast. and 1977. Deryck Guyler replaced Wilfrid Hyde-White from Lieutenant Dundas, Rachel Atkins as Trudi Schenk, Peter Producer: Helen Williams 1966. Sadly many episodes didn't survive in the archive, Marinker as Brigadier Erskine and Laura Molyneux as First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in August 2000. however the BBC's Transcription Service re-recorded 14 shows Slipstream. SAT 05:00 The Barchester Chronicles (b007jpr1) in 1980 - never broadcast in the UK, until the arrival of BBC Other parts played by Simon Treves, Sam Pamphilon, Alex Framley Parsonage Radio 4 Extra. -

August 2018 IL Calendar

SUN MON TUE WED THUR FRI SAT ROOM KEY 9:00 Step with Mark 2/P (ES) 9:00 Tai-Chi 1/P (ES) 9:15 Yoga 1/SP (ES) 10:00 Hopewell Furnace National WBD - (WBD) 9:00 Personal Training 1/P (FC) 9:00 Personal Training 1/P (FC) 10:00 Medication Drop Off in Cheryl's Office Historic Site 80th Birthday AS - Art Studio 10:00 Water Volleyball 2/P (P) 10:00 VIST Bank 1/SO (ML) 1/EN (WBD) Celebration 3/I (ML) 10:00 Yoga 1/SP (ES) 1 11:00 Pilates Body Conditioning 1/E (ES) 2 10:00 Water Volleyball 2/P (P) 3 10:00 Walk Away the Pounds 1/P (ES) 4 B - Brandywine 12:15 Mah-Jong 1/I (W) 11:00 Outdoor Quoits 2/P (AS) 10:15 Chair Yoga 1/SP (ES) 11:00 Water Zumba 2/P (P) BC - Business Center 1:00 Bridge 1/I (T) 11:00 From the Heart & Crave Cafe 2/ 12:15 Mah-Jong 1/I (T) 1:00 Bridge 1/I (T) ES - Exercise Studio 1:00 Balance Basics with Catina 1/P (ES) EN (ML) 1:00 Shillington Market & Goodwill 3/EN (ML) 5:30 Fabulous Cheeze Brothers & Sisters 60's & 70's FC - Fitness Center 1:30 Immanual UCC Mission Trip to Macon, Georgia 1:00 Japanese Calligraphy Class 1/I (AS) 1:00 Giant 2/SO (ML) Music @ Nissley Vineyard $18 2/E (ML) FC - Front Circle Presentation 1/SP (ES) 2:00 Learn CPR with Adrienne 1/HS (BC) 3:00 Pick Up Pool Games 1/I (GR) 7:00 Saturday Cinema/Les Miserables 1/SO (ES) GR - Game Room 3:00 Belly Dance with Cindy 2/E (ES) 2:00 Sit-er-cize 1/P (ES) 4:00 50/50 Tickets for Sale For Alzheimer's Walk 1/V (T) 6:00 Den & Terry @ New Holland 2/E (ML) 2:30 GHM Volunteering 1/V (ML) 4:00 First Friday Happy Hour with Wahl Street 1/SO (T) ML - Meet in Lobby 7:00 Pinochle -

©2013 Tal Zalmanovich ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2013 Tal Zalmanovich ALL RIGHTS RESERVED SHARING A LAUGH: SITCOMS AND THE PRODUCTION OF POST-IMPERIAL BRITAIN, 1945-1980 by TAL ZALMANOVICH A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Prof. Bonnie Smith And Approved by ---------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------- New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Sharing a Laugh: Sitcoms and the Production of Post-Imperial Britain, 1945-1980 By Tal Zalmanovich Dissertation Director: Bonnie Smith Sharing a Laugh examines the social and cultural roles of television situation comedy in Britain between 1945 and 1980. It argues that an exploration of sitcoms reveals the mindset of postwar Britons and highlights how television developed both as an industry and as a public institution. This research demonstrates how Britain metamorphosed in this period from a welfare state with an implicit promise to establish a meritocratic and expert-based society, into a multiracial, consumer society ruled by the market. It illustrates how this turnabout of British society was formulated, debated, and shaped in British sitcoms. This dissertation argues that both democratization (resulting from the expansion of the franchise after World War I) and decolonization in the post-World War II era, established culture as a prominent political space in which interaction and interconnection between state and society took place. Therefore, this work focuses on culture and on previously less noticed parties to the negotiation over power in society such as, media institutions, media practitioners, and their audiences. -

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Hitmakers: The Teens Who Stole Pop Music. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – Bobby Darin. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – [1] Leiber & Stoller; [2] Burt Bacharach. c2001. A & E Top 10. Show #109 – Fads, with commercial blacks. Broadcast 11/18/99. (Weller Grossman Productions) A & E, USA, Channel 13-Houston Segments. Sally Cruikshank cartoon, Jukeboxes, Popular Culture Collection – Jesse Jones Library Abbott & Costello In Hollywood. c1945. ABC News Nightline: John Lennon Murdered; Tuesday, December 9, 1980. (MPI Home Video) ABC News Nightline: Porn Rock; September 14, 1985. Interview with Frank Zappa and Donny Osmond. Abe Lincoln In Illinois. 1939. Raymond Massey, Gene Lockhart, Ruth Gordon. John Ford, director. (Nostalgia Merchant) The Abominable Dr. Phibes. 1971. Vincent Price, Joseph Cotton. Above The Rim. 1994. Duane Martin, Tupac Shakur, Leon. (New Line) Abraham Lincoln. 1930. Walter Huston, Una Merkel. D.W. Griffith, director. (KVC Entertaiment) Absolute Power. 1996. Clint Eastwood, Gene Hackman, Laura Linney. (Castle Rock Entertainment) The Abyss, Part 1 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss, Part 2 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: [1] documentary; [2] scripts. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: scripts; special materials. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – I. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – II. Academy Award Winners: Animated Short Films. -

Sarjassa Pitkän Jussin Majatalo

26 sLÄHIKUVA s1/2016 2AMI-ËHKË &- Rami Mähkä +ULTTUURIHISTORIA 4URUNYLIOPISTO BASIL FAWLTY JA "ESITHATCHERILAISUUS" SARJASSA PITKÄN JUSSIN MAJATALO Klassikkoaseman saavutanut tilannekomedia Pitkän Jussin majatalo raken- tuu pitkälti töykeän ja katastrofaltiin hotellinjohtajahahmo Basil Fawltyn toilauksille. Mielipiteiltään konservatiivinen ja patriootinen Fawlty on sarjan naurun ensisijainen kohde. Sellaisena hän artikuloi käsityksiä Britannian yh- teiskunnallisesta tilanteesta 1970-luvun jälkipuoliskolla. Sarjan avainteemojen kontekstualisointi – sarjan komediallisuus huomioon otaen – autaa ymmärtä- mään yhteiskunnallista ja kultuurista kehitystä, jonka seurauksena Margaret Thatcher nousi Britannian pääministeriksi vuonna 1979. Artikkelini tarkastelee Pitkän Jussin majataloa (Fawlty Towers, BBC, 1975, 1979) tilannekomediana, jonka keskipisteenä on hotellinomistaja ja -johtaja Basil Fawltyn (John Cleese) keskiluokkainen, konservatiivinen hahmo. Sarjan muut keskushahmot ovat Sybil Fawlty (Prunella Scales), Polly (Connie Booth) ja Ma- nuel (Andrew Sachs). Sybil on Basilin vaimo, joka on miestään sosiaalisempi ja avomielisempi. Hän myös osallistuu hotellin pyörittämiseen ollen siinä itse asiassa miestään pätevämpi. Sisäkkö Polly taas on taideopiskelija, joka toimii järjen äänenä ja Basilin virheiden paikkaajana. Neljäs keskushenkilö Manuel on huonosti englantia taitava ja asioita hahmottava espanjalaistarjoilija (ks. myös Wilmut 1980, 243–247). Jo tässä vaiheessa on syytä painottaa, että sitcomin hahmot tai niiden yhdistelmä perustuvat komediallisille