In Re Microstrategy, Inc. Sec. Litig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert A. Scandlon, Jr., Et Al. V. Blue Coat Systems, Inc., Et Al. 11-CV

Case3:11-cv-04293-RS Document14 Filed10/31/11 Page1 of 2 1 Nicole Lavallee (SBN 165755) Anthony D. Phillips (SBN 259688) 2 BERMAN DEVALERIO One California Street, Suite 900 3 San Francisco, CA 94111 Telephone: (415) 433-3200 4 Facsimile: (415) 433-6282 Email: [email protected] 5 [email protected] 6 Liaison Counsel for Proposed Lead Plaintiff Inter-Local Pension Fund and 7 Proposed Liaison Counsel for the Class 8 Mark S. Willis SPECTOR ROSEMAN KODROFF & 9 WILLIS, P.C. 1101 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW 10 Suite 600 Washington, DC 20004 11 Telephone: (202) 756-3600 Facsimile: (202) 756 3602 12 Email: [email protected] 13 Attorneys for Proposed Lead Plaintiff Inter-Local Pension Fund and 14 Proposed Lead Counsel for the Class 15 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 16 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 17 18 ROBERT A. SCANDLON, JR., On behalf of ) Himself and All Others Similarly Situated, ) No. CV 11-04293 (RS) 19 ) ) DECLARATION OF ROBERT M. 20 Plaintiff, ) ROSEMAN IN SUPPORT OF THE ) MOTION OF THE INTER-LOCAL 21 v. ) ) PENSION FUND’S MOTION FOR APPOINTMENT AS LEAD 22 BLUE COAT SYSTEMS, INC., BRIAN M. ) NESMITH and GORDON C. BROOKS, ) PLAINTIFF AND FOR APPROVAL 23 Defendants. ) OF ITS SELECTION OF LEAD ) COUNSEL 24 ) ) CLASS ACTION 25 ) ) Date: December 8, 2011 26 ) Time: 1:30 p.m. ) Dept.: Courtroom 3 27 ) Judge: Hon. Richard Seeborg 28 [CV 11-04293 (RS)] D ECL . OF ROBERT M. ROSEMAN ISO I NTER-LOCAL PENSION FUND ' S M OT. FOR A PPOINTMENT OF L EAD PL . & A PPOINTMENT OF LEAD COUNSEL Case3:11-cv-04293-RS Document14 Filed10/31/11 -

Top 100 for 1H 2015

` Top 100 for 1H 2015 Securities Class Action Services, LLC Published: September 28, 2015 Executive Summary ISS Securities Class Action Services tracked 61 settlements for the first half of 2015, up from from 53 settlements seen duringthe first half of 2014. Out of the 61 settlement agreements, five settlements ranked in the ISS Securities Class Action Services Top 100 for 1H 2015, which amounted for a 450 percent increase in settlement funds when compared to the same period in the previous year. The cases identified include: › American International Group, Inc. (2008) (S.D.N.Y.), which brought the highest settlement fund($900 million for approximately 200 eligible securities). › Bear Stearns Mortgage Pass-Through Certificates › IndyMac Mortgage Pass-Through Certificates (Individual & Underwriter Defendants) › Activision Blizzard, Inc. › Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) (2008) Out of the five settlements, four were filed in the federal courts during the midst of the financial credit crisis, while one was filed in the state court relating to the company’s private sale transaction. Two of the five were alleged violating Rule 10b-5 of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 (Employment of Manipulative and Deceptive Practices) while three were alleged violations of the Securities Act of 1933 (Civil Liabilities on Account of False Registration Statement). Two of the five settlements relate to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles and have restated their financial during the relevant periods. Of the five settlements, two were identified in the S&P Index. One SEC initiated settlement placed in the Top 30 SEC Disgorgement amounting to $200 Million. The Securities Class Action Services Tentative Settlement Pipeline stands $17.3 Billion as of 31 July 2015. -

List of Section 13F Securities

List of Section 13F Securities 1st Quarter FY 2004 Copyright (c) 2004 American Bankers Association. CUSIP Numbers and descriptions are used with permission by Standard & Poors CUSIP Service Bureau, a division of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. No redistribution without permission from Standard & Poors CUSIP Service Bureau. Standard & Poors CUSIP Service Bureau does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the CUSIP Numbers and standard descriptions included herein and neither the American Bankers Association nor Standard & Poor's CUSIP Service Bureau shall be responsible for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of the use of such information. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission OFFICIAL LIST OF SECTION 13(f) SECURITIES USER INFORMATION SHEET General This list of “Section 13(f) securities” as defined by Rule 13f-1(c) [17 CFR 240.13f-1(c)] is made available to the public pursuant to Section13 (f) (3) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 [15 USC 78m(f) (3)]. It is made available for use in the preparation of reports filed with the Securities and Exhange Commission pursuant to Rule 13f-1 [17 CFR 240.13f-1] under Section 13(f) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. An updated list is published on a quarterly basis. This list is current as of March 15, 2004, and may be relied on by institutional investment managers filing Form 13F reports for the calendar quarter ending March 31, 2004. Institutional investment managers should report holdings--number of shares and fair market value--as of the last day of the calendar quarter as required by Section 13(f)(1) and Rule 13f-1 thereunder. -

The Enron Failure and the State of Corporate Disclosure George Benston, Michael Bromwich, Robert E

Following the Moneythe The Enron Failure and the State of Corporate Disclosure George Benston, Michael Bromwich, Robert E. Litan, and Alfred Wagenhofer AEI-Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies 00-0890-FM 1/30/03 9:33 AM Page i Following the Money 00-0890-FM 1/30/03 9:33 AM Page iii Following the Money The Enron Failure and the State of Corporate Disclosure George Benston Michael Bromwich Robert E. Litan Alfred Wagenhofer - Washington, D.C. 00-0890-FM 1/30/03 9:33 AM Page iv Copyright © 2003 by AEI-Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies, the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Washington, D.C., and the Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without per- mission in writing from the AEI-Brookings Joint Center, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. Following the Money may be ordered from: Brookings Institution Press 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 Tel.: (800) 275-1447 or (202) 797-6258 Fax: (202) 797-6004 www.brookings.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data Following the money : the Enron failure and the state of corporate disclosure / George Benston . [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8157-0890-4 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Disclosure in accounting—United States. 2. Corporations—United States—Accounting. 3. Corporations—United States—Auditing. 4. Accounting—Standards—United States. 5. Financial statements—United States. 6. Capital market—United States. -

Adam Wisniewski | 373 Front St W, Toronto, Ontario [email protected] | 905-999-7514

Adam Wisniewski | 373 Front St W, Toronto, Ontario [email protected] | 905-999-7514 Highlights ● Cloudera certified CCA Spark and Hadoop Developer (CCA175) ● Over a decade of Full Stack development including disparate design, back end and front end development ● Recently focused on Big Data and Distributed Computing with a touch of Machine Learning Project X, Ltd. – Big Data Engineer June 2017 – Present ● Big Data pipeline, ETL, and Data Lake development for a large Canadian telecom client ◦ Architecting and development of Oozie based scheduled workflows ingesting and transforming diverse internal and external data sources ◦ Development of PySpark and Scala data transformation scripts ◦ Writing and optimizing Hive and Impala SQL queries and transformations ◦ Java development of Excel exporting functionality ● Historical and forecast weather reporting platform architected and developed from conception to production ◦ Python Celery scheduling backed by a Redis message queue back end ◦ Sourcing and automated retrieval of several NOAA weather data feeds ◦ Time series telemetry data stored in InfluxDB and presented in a Grafana user interface ◦ Main data store backed by the Elasticsearch JSON document storage engine ◦ Entire stack containerized in a Docker environment Format Inc. – Full Stack Developer May 2014 – April 2016 ● Implemented third party API integrations including Facebook, Twitter, Amazon S3, MailChimp, Disqus, Tumblr ● Led backend development team on new products such as Format Magazine ● Contributed to code in every level -

Microstrategy (MSTR) the Best Way to Own Bitcoin in the Stock Market Price Target $700

November 24, 2020 MicroStrategy (MSTR) The Best Way to Own Bitcoin in the Stock Market Price Target $700 To be clear, we are not recommending anyone to be long bitcoin. However, we’ve been asked our opinion on bitcoin by many of our readers, so here it is. The Citron Fund has a position in MSTR, which we believe is the best way to own Bitcoin. While we believe BTC is going higher, we cannot provide any deeper analysis than what has been overanalyzed by all. If you don't know Michael Saylor – it is time you do now. Watch any of these YouTube videos and you will understand why we are excited about Bitcoin and MSTR. https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=michael+saylor Three years ago, Citron was a vocal skeptic of bitcoin and particularly on low quality companies that soared on nothing more than hype such as Longfin and Riot Blockchain. https://www.cnbc.com/2017/12/19/infamous-short-seller-andrew-left-scrambling-for-ways-to-bet-against- bitcoin.html#:~:text=Infamous%20short%2Dseller%20Andrew%20Left%20scrambling%20for%20ways%20to%20be t%20against%20bitcoin,- Published%20Tue%2C%20Dec&text=Opportunities%20to%20short%2C%20or%20bet,on%20CNBC's%20%E2%80% 9CFast%20Money.%E2%80%9D Today, we are long bitcoin as we believe there is no better inflation hedge in the market. As stated by one of the greatest macro investors of our lifetime, Paul Tudor Jones, last month on CNBC: • “Bitcoin has a lot of the characteristics of being an early investor in a tech company… like investing with Steve Jobs and Apple, or investing in Google early” • “I think we are in the first inning of bitcoin and it’s got a long way to go” https://www.cnbc.com/video/2020/10/22/paul-tudor-jones-on-bitcoin-its-like-investing-early-in-a-tech- company.html © Copyright 2020 | Citron Research | www.citronresearch.com | All Inquiries – [email protected] November 24, 2020 For anyone who has tried to buy Bitcoin, it is a real pain in the ass with the constant fear that it can get stolen. -

Business Intelligence & Big Data On

Business Intelligence & Big Data on AWS Leveraging ISV AWS Marketplace Solutions October 2016 Contributors: Das Pratim, Rahul Bhartia, David Potes, Kim Schmidt, Jorge A. Lopez, and Luis Daniel Soto Business Intelligence & Big Data on AWS Oct 2016 Table of Contents Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Data Orchestration on AWS ................................................................................................................... 4 Data Collection Phase ............................................................................................................................ 5 Data Preparation Phase.......................................................................................................................... 6 AWS Marketplace ISV Solutions for Data Collection, Storing, Cleansing and Processing ............. 7 Data Visualization Phase for Reporting and Analysis ....................................................................... 11 AWS Marketplace ISV Solutions for Data Visualization, Reporting and Analysis .......................... 11 Analytical Platforms and Advanced Analytics Phase ....................................................................... 13 AWS Marketplace ISV Solutions for Advanced Analytics ................................................................ -

Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech

Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech) Center for the Development and Application of Internet of Things Technologies (CDAIT) IoT Thought Leadership Working Group Atlanta, Georgia, USA Georgia Tech Center for the Development and ApplicationNovemb of Interneter 2019 of Things Technologies (CDAIT) Page 1 of 78 PREFACE The topic for this white paper, Digital Transformation and the Internet of Things, was presented by the Center for the Development and Application of Internet of Things Technologies (CDAIT) IoT Thought Leadership Working Group1, headed by Karen I. Matthews, Ph.D. and Technology and Market Development Manager, Science and Technology at Corning Incorporated, and was approved for creation October 2018 by the CDAIT Executive Advisory Board. The CDAIT IoT Thought Leadership Working Group, along with other CDAIT collaborators, subsequently authored this paper for publication. The key contributors, listed at the end of the paper, come from different walks of industry and academia and are directly involved in Digital Business Transformation and the building of IoT. Special thanks goes to Michelle Mindala-Freeman, former Vice President in the Telecommunications, Media and Technology Practice at Capgemini; Pramod Kalyanasundaram, Ph.D., former Vice President and CTO at Verizon Connect; and Sébastien Lafon former Global Head of Digital and Marketing Services at Boehringer Ingelheim, all Georgia Tech Visiting Scholars at CDAIT, who animated and guided the team’s effort. Following the same approach as for other CDAIT publications, contributors have shared their personal ideas, observations and opinions grounded in research and real-life experience. As a result, the views expressed in this white paper are solely the authors’ collective own and do not necessarily represent those of Georgia Tech, the CDAIT company members, the individual members of the IoT Thought Leadership Working Group, the University System of Georgia or the State of Georgia. -

Tips & Tricks to Monitor, Manage & Optimize Microstrategy System

Tips and Techniques on how to better Monitor, Manage and Optimize your MicroStrategy System By: InfoCepts Jan 2013 High ROI DW and BI Solutions Brief Overview of InfoCepts High ROI DW and BI Solutions Helping Our Customers Derive Value from Their Data since 2004 . High quality global delivery model with savings of up to 40% . Founded and led by ex-MicroStrategists . 350+ people devoted to delivering BI, DW 355 and Integration Solutions 250 . We have one of the largest Global pools of MicroStrategy Consultants 167 . 8 years of growth driven largely by referrals 111 and increasing levels of responsibility 71 . Focus on culture and excellence 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 High ROI DW and BI Solutions Our Services Data Management BI Strategic Services BI Application Development & Management . Data Governance & . Enterprise Information . Business Analytics Stewardship Strategy and Planning . Text Analytics . Data Quality . BI Metrics . Predictive Analytics Management . Data Integration . BI Application . Unstructured Data . BI Centers of Customization Excellence Program Integration . Administration and . Metadata Management Technology – Managed . Master Data Services Management . Program/Project . Data Analysis Management . Data Design High ROI DW and BI Solutions Our Capabilities Span across Industries and Technologies Technologies BI MicroStrategy, IBM Cognos, Microsoft BI, Pentaho, TIBCO Spotfire, Tableau, OBIEE Data Integration Informatica, SQL Scripts, Microsoft SSIS, Oracle Data Integrator, Talend Databases Oracle, Microsoft SQL Server, IBM -

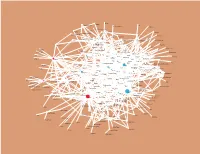

Sun IBM Walmart Blockbuster Circuitcity Gateway SBC

Netopia Tellabs JuniperNetworks GE NetworkSolutions Citibank GeneralInstrument Lumeta Fujitsu CheckPoint Siemens SonusNetworks Juno CharlesSchwab NetZero Harbinger GM Broadcom Alcatel NetworkAssociates Lucent BofA ComputerAssociates MicroStrategy Tibco CommerceOne Netegrity Ericsson AmEx GlobalCrossing ALLTEL Verizon VeriSign PwC UPS MapInfo Lawson RIM RSA AnswerThink KMart NortelNetworks 3COM i2 CheckFree MasterCard Verity VISA BaltimoreTechnologies Handspring AvantGo Macromedia SAP CareerMosaic Livelink Nokia ATG Motorola Palm CIBER JDEdwards MP3.com BT Unisys Interwoven Staples Qualcomm Yahoo! Ariba Veritas EMC Oracle Peoplesoft Sun FoundryNetworks EDS Ford Sprint DeloitteToucheTohmatsu divine WebMethods Drugstore Adobe IBM E.piphany iPlanet HP Siebel BMCSoftware CSC bowstreet Borders Agency.com Vodafone Cisco Amazon Novell Intel AT&T Kana ExodusComm WebTrends BroadVision ToysRUs Monster KPNQwest Vignette InfoSpace CDNow Nextel D&B CacheFlow METAGroup Accenture BEASystems Apple Interliant Participate.com AP Sony NewsCorp Kodak Loudcloud C|Net SoftBank KPMG SAS GartnerGroup TARGET EarthLink Fidelity Compaq RedHat RealNetworks BankOne Universal Dell moreover.com ForresterResearch OfficeMax C&W CNN Travelocity XOComm. RadioShack AberdeenGroup E*Trade VerticalNet AltaVista CircuitCity Audible Akamai MSFT McAfee WebMD Inktomi Cablevision Samsung SportsLine InterNap QXL.com CVS MediaOne theStreet AOL WalMart BestBuy Buy.com Teleglobe CMGI NBC Starbucks Gateway CapGemini BellSouth RoadRunner AskJeeves DigitalIsland Blockbuster CBS Excite TerraLycos PivotalSoftware Intuit NTT Slate ViacomCBS Genuity SBC Comcast LookSmart LibertyMedia Spyglass eLance IDT Disney/ABC BellCanada B&N NaviSite AAdvantage EMI DoubleClick Net2Phone eBay Prodigy Netcentives Kinko's LiquidAudio MapQuest Bertelsmann Oxygen MercuryInteractive WellsFargo Level3 AutoTrader Sears CareerBuilder napster USATODAY Pajek. -

November 16, 2020

Investor Day November 16, 2020 Intelligence Everywhere Copyright © 2020 MicroStrategy Incorporated. All Rights Reserved. Safe Harbor Statement Forward-Looking Statements Some of the information we provide in this presentation regarding our future expectations, plans, and prospects may constitute forward-looking statements. Actual results may differ materially from these forward- looking statements due to various important factors, including the risk factors discussed in our most recent 10- Q filed with the SEC. We assume no obligation to update these forward-looking statements, which speak only as of today. Also, in this presentation, we will refer to certain non-GAAP financial measures. Reconciliations showing GAAP versus non-GAAP results are available in the appendix of this presentation, which is available on our website at www.microstrategy.com. Intelligence Everywhere Copyright © 2020 MicroStrategy Incorporated. All Rights Reserved. 2 Presenters Michael Saylor Phong Le Tim Lang Hugh Owen Chairman and President and Chief Technology Officer Chief Marketing Officer Chief Executive Officer Chief Financial Officer Intelligence Everywhere Copyright © 2020 MicroStrategy Incorporated. All Rights Reserved. 3 Agenda Introduction Phong Le, President and CFO Company Vision Michael J. Saylor, Chairman and CEO Product Update and Shift to Cloud Timothy Lang, CTO Demand Generation and Productive Growth Hugh Owen, CMO Finance and Growth Phong Le, President and CFO Q & A Intelligence Everywhere Copyright © 2020 MicroStrategy Incorporated. All Rights -

Securities Class Action Services

Securities Class Action Services Securities Class Action Services The SCAS 100 for 2H 2012 The SCAS “Top 100 Settlements Semi-Annual Report” identifies the largest securities class action settlements filed after the passage of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, ranked by the total value of the settlement fund. The Top 100 Settlements Semi-Annual Report provides a wealth of information, including the settlement date, filing court, settlement fund, and identifies the key players for each settlement. The report, which is updated and circulated semi-annually, is broken down into following categories: SCAS Top 100 Settlements Semi-Annual Report The Front Page provides the complete list of the Top 100 Securities Class Action Settlements, ranked according to the Total Settlement Amount, and provides information on the filing court, settlement year and settlement fund. The SCAS Top 100 does not include non-US cases and the SEC disgorgements. Cases with the same settlement amount are given the same ranking. For cases with multiple partial settlements, the amount indicated in the Total Settlement Amount is computed by combining all partial settlements. The settlement year reflects the year the most recent settlement received final approval from the Court. Cases in the Top 100 settlements are limited to those that have been filed on or after January 1, 1996. Only final settlements are included. Data on SEC settlements are not included, but rather compiled in a separate list—the Top 30 SEC Disgorgements. No. of Settlements Added to SCAS 100 (1996-2012) The Top 100 Settlements from 1996-2012 section provides a chart of the cases in the Top 100 Settlements Semi-Annual Report, categorized by Settlement Year.