Economic Development: Resolving the Parallel Universe Dilemma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rosin &Associates

BROOKLYN BRIDGE PARK ASSESSMENT ANALYSIS AS OF FEBRUARY 9, 2016 FOR MR. MARTIN HALE PEOPLE FOR GREEN SPACE FOUNDATION INC. 271 CADMAN PLAZA EAST STE 1 PO BOX 22537 BROOKLYN, NY 11201 BY ROSIN & ASSOCIATES 29 WEST 17TH STREET, 2ND FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10011 DATE OF REPORT: FEBRUARY 9, 2016 © ROSIN & ASSOCIATES 2016 29 West 17th Street, 2nd Floor ROSIN & ASSOCIATES New York, New York 10011 Tel: (212) 726-9090 Valuation & Advisory Services February 9, 2016 Mr. Martin Hale People For Green Space Foundation Inc. 271 Cadman Plaza East Ste 1 PO Box 22537 Brooklyn, NY 11201 Re: Brooklyn Bridge Park Assessment Analysis Dear Mr. Hale, As requested, we have reviewed the following in order to determine the plausibility of the parameters set forth therein: 1. “Financial Model Update: Public Presentation” presented to the public by Brooklyn Bridge Park Corporation (BBPC) report for Brooklyn Bridge on dated July 9, 2015. 2. Analysis of Brooklyn Bridge Park completed by Barbara Byrne Denham, titled “Report on Brooklyn Bridge Park’s Financial Model” dated July 2015. Rosin & Associates was hired to perform a market analysis of Brooklyn Bridge Park and the surrounding areas in order to determine if the market supports the BBPC model’s assessment base, which features in the Denham Analysis as well as Denham’s own research set forth in her report. It has been a pleasure to assist you in the assignment. If you have any questions concerning the analysis, or if Rosin & Associates can be of further service, please contact us at (212) 726-9090. Respectfully submitted, -

Public Design Commission Conceptual Presentation on Open

PUBLIC DESIGN COMMISSION FINAL REVIEW JANUARY 19, 2021 WILLOUGHBY SQUARE OPEN SPACE NEW YORK CITY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION HARGREAVES JONES LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE GARRISON ARCHITECTS // DELTA FOUNTAINS // TILLETT LIGHTING LANGAN // WESLER-COHEN ASSOCIATES // PAUL COWIE & ASSOCIATES // CRAUL LAND SCIENTIST NORTHERN DESIGN // SITEWORKS // MILROSE CONSULTANTS THE ORATORY CHURCH OF ST 4 METROTECH CENTER DELI BONIFACE CHURCH (1ST FL) (JP MORGAN CHASE & CO) FLATBUSH AVENUE BROOKLYN BROOKLYN SAVANNA DEVELOPMENT (141 WILLOUGHBY STREET) Manhattan New Jersey WILLOUGHBY WILLOUGHBY STREET SQUARE Brooklyn AVA DOBRO Staten Island BROOKLYN POINT MIXED USE - RESIDENTIAL/COMMERCIAL BRIDGE STREET DUFFIELD STREET ALOT WILLOUGHBY FLATBUSH AVENUE GOLD STREET / ALBEE SQUARE (W HOTELS) SQUARE CITY NTS East Brooklyn SHERATON Bridge BROOKLYN River Park Cadman Navy Plaza Flatbush Ave Ext Yard Flushing Ave Clark St Cadman Plaza W Commodore Barry Park 227 DUFFIELD 230 DUFFIELD ST STREET Pierrepont St Brooklyn-Queens Expwy Tillary St (TOWNHOUSE) Johnson St HOTEL INDIGO CITY POINT (299 DUFFIELD STREET) (7 DEKALB AVENUE) Henry St Myrtle Ave Clinton St Ft Greene Gold St Duffield St Bridge St Willoughby St Park OFFERMAN Vanderbilt Ave ONE WILLOUGHBY SQUARE WILLOUGHBY Bklyn BUILDING MIXED USE - SCHOOL/OFFICE Fulton St Long Island Hospital SQUARE University Center Dekalb Ave Adams St Smith St BRIQ Hoyt St (237 DUFFIELD STREET) Bond St Atlantic St Nevins St THE AZURE (436 ALBEE SQUARE) Brooklyn-Queens Expwy NEIGHBORHOOD 1000’ SITE N RESIDENTIAL MIXED-USE SCALE: NTS -

Eric L. Adams'

Borough President Adams joined the family of the late Dr. John Elefterakis and community leaders in cutting the ribbon for the dedication of Dr. John’s Playground in his memory across from PS 277 LATEST INITIATIVES Gerritsen Beach School in Gerritsen Beach. On Thursday, May 3rd, Borough President Adams fully publicly-financed municipal elections. Council would display information online for both the tenant and Photo Credit: Erica Sherman/Brooklyn BP’s Oce announced the impact of his $1 million capital budget Member Albanese has campaigned across New York City for owner to view freely. In response to the legislation’s investment in Fiscal Year 2019 (FY19) of PB, a democratic a more robust public financing system, and Borough introduction, which he originally called for in 2016, Borough process in which local residents directly decide how to President Adams armed that this would be his priority on President Adams stated, “take it from The New York Times’ spend part of a public budget, which increased the number the new commission in testimony he submitted in March to own words yesterday: there is an eviction machine churning of community-driven projects funded in council districts the City Council’s Committee on Governmental its way through New York City. We’ve been playing catch up that encompass more than 60 percent of Brooklyn. Tens of Operations. Rather than New York City’s existing limited to these bad actors because we’ve been using an abacus in an thousands of Brooklyn residents cast ballots at locations matching funds system, Borough President Adams advocat- iPhone era. -

Find Dandelion Yellow Giveaway Packs at These Stores

find Dandelion Yellow giveaway packs at these stores Store Name Address City Zip-code Phone No Store Name Address City Zip-code Phone No Aberdeen 3316 7th Ave SE Birmingham 35226 (205) 747-1654 Latham 675 Troy Madison 35758 (256) 690-5890 Abilene 3710 Ridgemont Dr Birmingham 35235 (205) 655-6950 Schenectady Rd Green 762 Arlington Rdg Birmingham 35242 (205) 408-7687 East Greenbush 625 3rd Ave Ext Mobile 36695 (251) 607-0265 Cuyahoga Falls 449 Howe Ave Decatur 35601 (256) 898-3036 Saratoga Springs 3031 Route 50 Montgomery 36117 (334) 356-6265 Macedonia 8282 Golden Link Blvd Dothan 36303 (334) 340-1112 Niskayuna 428 Balltown Rd Opelika 36801 (334) 705-0152 Stow 4200 Kent Rd Florence 35630 (256) 764-6924 Glenville 204 Saratoga Rd Oxford 36203 (256) 231-2900 ALABAMA ALABAMA Albany 2255 14th Ave SE Homewood 35209 (205) 994-7531 Albuquerque 8510 Montgomery Tuscaloosa 35404 (205) 462-1064 Wyoming Blvd NE Clifton Park 26 Crossing Blvd Huntsville 35802 (256) 650-3491 Colonie Northway 1440 Central Ave Huntsville 35806 (256) 922-0189 Anchorage NE 1200 N Muldoon Anchorage 99504 (907) 269-2100 Wasilla 1801 E Parks Hwy Wasilla 99654 (907) 631-7200 Rd Ste F Anchorage South 150 W 100th Anchorage 99515 (907) 267-7500 Ave Ste A ALASKA ALASKA Chandler West 3425 W Frye Rd Chandler 85226 (480) 281-0007 South Mountain 2140 E Baseline Rd Phoenix 85042 (602) 281-1119 Santan Deer Valley 16806 N 7th St Phoenix 85022 (602) 794-3601 Chandler South 3777 S ARIZONA AVE Chandler 85248 (480) 612-6101 Phoenix Spectrum 5715 N 19th Ave Phoenix 85015 (602) 308-3604 Flagstaff -

A Specific Look Into Downtown Brooklyn's Albee Square Daniel Cartagena

A specific look into Downtown Brooklyn’s Albee Square Daniel Cartagena Dekalb Market When driving along Flatbush ave one couldn’t help but notice these colored shipping containers stacked upon one another with the words Dekalb Market painted on them. Along with the colorful striped fencing the site made quite an impression. Upon entry one was engulfed into a space that felt alienat- ed from the standard vernacular of New York City. The space was designed as a courtyard that had been surrounded with containers that were had been retrofitted to have windows and doors to create a storefront vernacular. The stores were eclectic and varied from jewelry to clothing and even art. At one end there was equality. The site itself is called Albee Square, the more retail style storefronts but at the oth- it was named after Edward Franklin Albee. Al- er one would find an array of picnic tables and bee was a theatrical manager who, as the gen- food sellers that were all organic and healthy eral manager of the Keith-Albee theatre circuit, using the garden integrated in the site for was the most influential person in vaudeville their needs as well as to show, those interest- in the United States. Albee was president of ed, in how to cultivate and harvest in the city. the United Bookings Office from its forma- Dekalb Market was born out of two key issues; tion in 1900. In 1916 he organized a union, it is a large space in Downtown Brooklyn that the National Vaudeville Artists, thus gaining a has always been at the center of contestation near monopoly on both talent and production and its created a struggle between power and in U.S. -

Mayor Bloomberg Highlights Some of the Many Free and Low- Cost Activities Available This Summer to New Yorkers and Their Families

THE CITY OF NEW YORK OFFICE OF THE MAYOR NEW YORK, NY 10007 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 26, 2012 No. 245 www.nyc.gov MAYOR BLOOMBERG HIGHLIGHTS SOME OF THE MANY FREE AND LOW- COST ACTIVITIES AVAILABLE THIS SUMMER TO NEW YORKERS AND THEIR FAMILIES Call 311 or Visit NYC.gov for More Information on these Events and Many Others Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg today outlined some of the free and low-cost, family- friendly cultural activities occurring throughout the five boroughs this summer. There are countless opportunities for New Yorkers and visitors to experience the creativity that makes New York City a great place to live, work and visit. New York City offers hundreds of events, exhibits and performances that are free or low-cost to the public. Call 311 or visit NYC.gov for more information on these and other programs. “All year-round, New York City is the best place in the world to experience arts and culture, and this summer, free events will transform our neighborhoods into dynamic stages for performances, exhibitions, movies and more,” said Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg. “The City is proud to work with cultural organizations from across the five boroughs to provide access to dynamic creative programming for New Yorkers and the record number of tourists who will visit our city this summer.” FESTIVALS AND CONCERTS The Downtown Brooklyn Partnership presents “Performing the Streets” The Downtown Brooklyn Partnership and the Downtown Brooklyn Arts Alliance present “Performing the Streets.” On Fridays in June, visit Downtown Brooklyn for outdoor performances at Albee Square (Fulton St & Bond St) and Renaissance Plaza (between Jay St & Adams St, adjacent to the Marriott Hotel). -

Brooklyn: the Bridge to the Future TABLE of CONTENTS • MARKETING REPORT • Q1 2016

Brooklyn Offce North Brooklyn The What MARKETING and Residential Brooklyn Tech Triangle The Why REPORT Development South of Atlantic Ave The Result Q1 2016 Brooklyn: The Bridge to the Future TABLE OF CONTENTS • MARKETING REPORT • Q1 2016 Brooklyn: The Bridge to the Future 1 A boom in living and working in Brooklyn: What’s driving it? - 2 3 North Brooklyn: - Greenpoint | Williamsburg | Bushwick 4 - 5 6 Brooklyn Tech Triangle: - Dumbo | Downtown Brooklyn | Brooklyn Navy Yard 7 - 8 9 South of Atlantic Ave: What’s Next? - Gowanus | Red Hook | Sunset Park 10 - 11 The Result 12 13 Recent Sales | Contact | About GFI Realty Services - 14 140 BROADWAY 41ST FLOOR | NEW YORK, NY 10005 P: (212) 837.4665 | E: [email protected] INTRODUCTION • MARKETING REPORT • Q1 2016 1 A boom in living and working in Brooklyn: What’s driving it? Due to Brooklyn’s exponential year-over-year residential and retail growth, combined with the staggering number of units in the pipeline, it’s nearly impossible to ignore the development currently taking place in Brooklyn. With the explosive growth of the borough’s population, particularly among millennials, and the borough’s emergence as an incubator for TAMI (Technology, Advertising, Media and Innovation) companies, we are seeing waves of developers “crossing the bridge” as they seek new investment opportunities. his trend began in Northern Brooklyn, with Tthe emergence of neighborhoods such as Greenpoint, Williamsburg and Bushwick, Residential 2015 By end of 2016 and has moved south, particularly in water- Growth front neighborhoods, to the Navy Yard, Down- 2,700 5,000 town Brooklyn, DUMBO, Gowanus, Red Hook and Sunset Park. -

Art Commission Meeting Agenda Monday, June 16, 2008

Art Commission Meeting Agenda Monday, June 16, 2008 Public Meeting 1:25 p.m. Consent Items 23160: Reconstruction of Engine Company 63/Ladder 39/Battalion 15, including the construction of an addition, 755 East 233rd Street, Bronx. (Preliminary) (CC 12, CB 12) DDC 23161: Reconstruction of the entrance, Queensboro Hill Community Library, 60- 05 Main Street, Queens. (Final) (CC 20, CB 7) DDC 23162: Installation of 16 signs as part of a campus-wide wayfinding signage program, New York Presbyterian Hospital and Columbia University Medical Center, West 168th Street, St. Nicholas Avenue, West 165th Street and Riverside Drive, Manhattan. (Preliminary and Final) (CC7 & 10, CB 12) DOT 23163: Installation of four fenced-in planted areas, 15 Central Park West, Manhattan. (Preliminary and Final) (CC 6, CB 7) DOT 23164: Installation of a planted area, LaGuardia Center, 45th Street between Ditmars Boulevard and 23rd Avenue, Queens. (Preliminary and Final) (CC 22, CB 401) DOT 23165: Installation of 22 M-poles, 86th Street between Fourth Avenue and Fort Hamilton Parkway, Brooklyn. (Preliminary and Final) (CC 43, CB 10) DOT 23142: Installation of streetscape improvements, including the reconstruction of Albee Square, Fulton Mall, Fulton Street from Adams Street to Flatbush Avenue, Brooklyn. (Final) (CC 33, CB 2) EDC/DOT 23166: Reconstruction of the Arthur Avenue Retail Market, 2344 Arthur Avenue, Bronx. (Final) (CC 15, CB 6) EDC 23167: Construction of an environmental education center and rehabilitation of and addition to the current facility, including adjacent site work, New York Restoration Project’s Sherman Creek Campus, Sherman Creek Park, 10th Avenue, Harlem River Drive, Academy Street and Sherman Creek, Manhattan. -

Protest & Comments in Response to NYISO Demand Curve

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BEFORE THE FEDERAL ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION ) New York Independent System Operator, Inc. ) Docket No. ER21-502-000 ) PROTEST AND SUPPORTING COMMENTS OF INDEPENDENT POWER PRODUCERS OF NEW YORK, INC. On November 30, 2020, the New York Independent System Operator, Inc. (“NYISO”) filed, pursuant to Section 205 of the Federal Power Act, proposed tariff revisions to its Market Administration and Control Area Services Tariff (“Services Tariff”), which define new installed capacity (“ICAP”) Demand Curves applicable for the 2021/2022 Capability Year and proposed the inputs and parameters for conducting the annual updates to determine the ICAP Demand Curves for the 2022/2023, 2023/2024, and 2024/2025 Capability Years, with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (“Commission”) in the above-captioned docket.1 Pursuant to Rule 211 of the Commission’s Rules of Practice and Procedure, 18 C.F.R. § 385.211, and the Commission’s Combined Notice of Filings #1, issued on November 30, 2020, Independent Power Producers of New York, Inc. (“IPPNY”)2 hereby protests, and comments on, the NYISO Filing. I. BACKGROUND AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On May 20, 2003, the Commission first approved ICAP Demand Curves for the NYISO ICAP market to replace a critically flawed capacity market structure that had led to severely 1 Docket No. ER21-502-000, New York Independent System Operator, Inc., 2021-2025 ICAP Demand Curve Reset Proposal (Nov. 30, 2020) (“NYISO Filing”). 2 IPPNY is a not-for-profit trade association representing the independent power industry in New York State. Its members include companies involved in the development and operation of electric generating facilities and the marketing and sale of electric power in New York. -

Council Won't Listen

WIN A MAGNIFICENT HONEYMOON CRUISE — EASY ENTRY ON PAGE 2 BROOKLYN’S REAL NEWSPAPERS Including The Brooklyn Heights Paper, Carroll Gardens-Cobble Hill Paper, DUMBO Published every Saturday — online all the time — by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, Paper and 55 Washington St, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY the Downtown News 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.Br ooklynPapers.com • © 2005 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 20 pages •Vol.28, No. 23 BWN •Saturday, June 4, 2005 • COUNCIL WON’T LISTEN FREE Public barred from hearing on Ratner plan By Jess Wisloski The Brooklyn Papers ment testimonials by elected offi- The only public hearing before cials and representatives of the de- a committee of the City Council veloper, Forest City Ratner, to go on project’s footprint. on the Atlantic Yards project was for more than two hours. The room designated for the held in a room so small that “The general public didn’t get to hearing, at 250 Broadway, one dozens of people — including, speak,” said Daniel Goldstein, a block from City Hall, had only 50 for a time, Borough President persistent critic of the plan to build chairs, but at least 100 people Marty Markowitz — were barred high-rise housing and office build- showed up. by police from entering. ings as well as an arena for the The room was crowded early by New Jersey Nets. organized proponents of the Ratner “I’m supposed to be in there,” Even for those who did get into project, including trade union Markowitz yelled at the officers. the May 26 hearing, there was little “[Committee Chairman James] members and members of BUILD Gesturing to the officials inside, he time for public input, although the Sanders cut it off at five [o’clock] (Brooklyn United for Innovative asked an aide, “Do they know who committee allowed pro-develop- for no apparent reason other than he just felt like leaving,” said Gold- Local Development). -

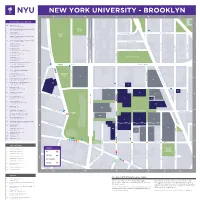

Directions to NYU Washington Square Campus Directions to NYU Washington Square Campus 5 ATM - Chase Bank (D-3) 5 Metrotech Ctr

. E A Z A L P NEW YORKAN UNIVERSITY - BROOKLYN M D A B C D NASSAU STREET E CA NYU Buildings & Destinations 16 Admissions (D-3) Wunsch Hall • 311 Bridge St. WALT 5 Bern Dibner Library of Science & Technology WHITMAN (D-3) • 5 MetroTech Ctr. B 1 PARK ROOK 1 6 Café & Servery (C-3) CONCORD STREET CADMAN CONCORD STREET L Rogers Hall • 6 MetroTech Ctr. Y PLAZA N Q 1 Center for Urban Science + Progress (CUSP) PARK U EEN T T (C-4) • 1 MetroTech Ctr. E E E S E E E 20 Center for Urban Science + Progress (CUSP) X P (A-3) • 1 Pierrepont Plaza ENAD CHAPEL STREET Y T M E T MS STR MS STR (C-3) T 6 Computer Lab E RO C E A A E Jacobs Academic Building P A D D D 6 MetroTech Ctr. A A M GE STR A E DUMBO Incubator D N C 20 Jay Street • (Not located on map) CATHEDRAL PLACE N P OLD STRE L BRI RI G A P 6 Greenhouse (C-3) N Z DUFFIELD STRE T Jacobs Academic Building A E 6 MetroTech Ctr. W . MCLAUGHLIN PARK 6 Gymnasium (C-3) Jacobs Academic Building BROOKLY AY STRE 6 MetroTech Ctr. J 6 Information Technology Help Desks (C-3) 2 2 Rogers Hall • 6 MetroTech Ctr. 25 38 103 TILLARY STREET TILLARY STREET 6 Jacobs Academic Building (C-3) 6 MetroTech Ctr. FLATBUSH 26 . 6 Jacobs Administration Building (C-3) 41 A E 6 MetroTech Ctr. T Z 52 E E (D-3) KOREAN WAR LA 5 LC400 Event Space A P Bern Dibner Library Building VETERANS V N PLAZA STR E 5 MetroTech Ctr. -

REC-U-U-USE ME! Dolly Sits out Atlantic Yards Review, Keeps Nets Investment, Leaving Brooklyn with No Voice

E I D BROOKLYN S PLUS I N Nightlife Where to FITNESS SPECIAL CALENDAR OF EVENTS BROOKLYN’S REAL NEWSPAPERS Including Windsor Terrace, Sunset Park, Midwood, Kensington, Ocean Parkway Papers Published every Saturday — online all the time — by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington St, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2005 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 18 pages •Vol. 28, No. 12 BWN • Saturday, March 19, 2005 • FREE REC-U-U-USE ME! Dolly sits out Atlantic Yards review, keeps Nets investment, leaving Brooklyn with no voice By Jess Wisloski est development proposal because, interest, although the city’s Con- each borough president is repre- The Brooklyn Papers as first reported by The Brooklyn flicts of Interest Board has yet to sented, along with an appointee of Brooklyn’s sole appointee Papers last August, she owns a render a determination one way the public advocate and seven to the City Planning Com- stake in the New Jersey Nets, a or the other. mayoral appointees. Markowitz’s planning commission spokes- A City Planning Commission 2003 appointment of Williams to mission, one of only two city woman said this week. spokeswoman told The Papers the powerful planning commis- agencies with an official role Nets principal owner Bruce this week that while the commis- sion made her a key player in the in the proposed Atlantic Yards Ratner wants to move the basket- sion would have a minor role in city’s land use approval process. arena, housing and office ball team to an arena he would review of the Ratner plan, prima- The City Planning Commis- complex will have no voice, build at the intersection of Flat- rily ratifying the state’s right to sion is the only city authority oth- the city said this week.