The Macquarie Bicentennial: a Reappraisal of the Bigge Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish in Australia

THE IRISH IN AUSTRALIA. BY THE SAME AUTHOR. AN AUSTRALIAN CHRISTMAS COLLECTIONt A Series of Colonial Stories, Sketches , and Literary Essays. 203 pages , handsomely bound in green and gold. Price Five Shillings. A VERYpleasant and entertaining book has reached us from Melbourne. The- author, Mr. J. F. Hogan, is a young Irish-Australian , who, if we are to judge- from the captivating style of the present work, has a brilliant future before him. Mr. Hogan is well known in the literary and Catholic circles of the Australian Colonies, and we sincerely trust that the volume before us will have the effect of making him known to the Irish people at home and in America . Under the title of " An Australian Christmas Collection ," Mr. Hogan has republished a series of fugitive writings which he had previously contributed to Australian periodicals, and which have won for the author a high place in the literary world of the. Southern hemisphere . Some of the papers deal with Irish and Catholic subjects. They are written in a racy and elegant style, and contain an amount of highly nteresting matter relative to our co-religionists and fellow -countrymen under the Southern Cross. A few papers deal with inter -Colonial politics , and we think that home readers will find these even more entertaining than those which deal more. immediately with the Irish element. We have quoted sufficiently from this charming book to show its merits. Our readers will soon bear of Mr. Hogan again , for he has in preparation a work on the "Irish in Australia," which, we are confident , will prove very interesting to the Irish people in every land. -

Westerly Magazine

latest release DECADE QUARRY a selection of a selection of contemporary contemporary western australian western australian short fiction poetry edited by edited by B.R. COFFEY . FAY ZWICKY Twenty-one writers, including Peter Cowan, Twenty-six poets, includes Alan Alexander, Elizabeth Jolley, Fay Zwicky, Margot Luke, Nicholas Hasluck, Wendy Jenkins, Fay Zwicky, James Legasse, Brian Dibble and Robin Sheiner. Ian Templeman and Philip Salom. ' ... it challenges the reader precisely because it 'The range and quality of the work being done offers such lively, varied and inventive stories. is most impressive' - David Brooks. No question here of recipe, even for reading, ' ... a community of voices working within a much less for writing, but rather a testimony to range of registers, showing us how we are the liveliness and questioning' - Veronica Brady. same but different in our private responses . .' recommended retail price: $9.95 - James Legasse. recommended retail price: $6.00 SCARPDANCER DESERT MOTHER poems by poems by ALAN PHIUP COLliER ALEXANDER Sazrpdoncer consolidates Alan Alexander's Desert Mother introduces a new poet with a reputation as one of Australia's finest lyric fme wit and a marvellously exact ear for the poets. He is a poet of great flexibility and tone, style and idiosyncrasies of language. fmesse whose origins are clearly with the Irish Philip Collier is a poet who has developed tradition of post-Yeatsean lyricism. himself a lively and refreshingly original voice. West Coast Writing 14 West Coast Writing 15 recommended -

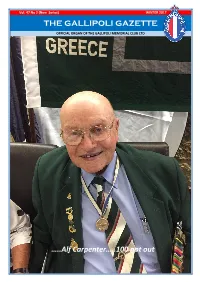

Alf Carpenter…..100 Not Out

Vol. 47 No 2 (New Series) WINTER 2017 THE GALLIPOLI GAZETTE OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE GALLIPOLI MEMORIAL CLUB LTD …..Alf Carpenter…..100 not out 1 EDITORIAL…….. This edition carries a full report on the Gallipoli Art celebration and presented Alf Carpenter with a Prize which again attracted a broad range of entries. certificate of Club Life Membership. We also look at the commemoration of Anzac Day The elevation of John Robertson to Club President at the Club which included the HMAS Hobart at the April Annual Meeting sees the continuity of Association and was highlighted by the 2/4th the strong leadership the Club has benefitted from Australian Infantry Battalion Reunion which over past decades since the Club was lifted out of doubled as celebration of the 100th birthday three financial uncertainty in the early 1990s. "Robbo" days earlier of its Battalion Association President for joined the Committee in 1991 along with outgoing the past 33 years, Alf Carpenter. President Stephen Ware and myself. So, I know first- The numbers at the reunion lunch were bolstered hand of John's strong commitment over many years by the many friends Alf has made among the to the Club and its ideals. The Club also owes a families of his World War Two mates and the massive debt to retiring President Stephen Ware, support he has given to those families as the ranks who has stepped down to be a Committee member of the 2/4th diminished over the years. The new for continuity. Thank you Stephen for your visionary Gallipoli Club President, John Robertson, joined the leadership and prudent financial management over three decades. -

Culture and Customs of Australia

Culture and Customs of Australia LAURIE CLANCY GREENWOOD PRESS Culture and Customs of Australia Culture and Customs of Australia LAURIE CLANCY GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Clancy, Laurie, 1942– Culture and customs of Australia / Laurie Clancy. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–32169–8 (alk. paper) 1. Australia—Social life and customs. I. Title. DU107.C545 2004 306'.0994 —dc22 2003027515 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2004 by Laurie Clancy All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2003027515 ISBN: 0–313–32169–8 First published in 2004 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Neelam Contents Preface ix Acknowledgments xiii Chronology xv 1 The Land, People, and History 1 2 Thought and Religion 31 3 Marriage, Gender, and Children 51 4 Holidays and Leisure Activities 65 5 Cuisine and Fashion 85 6 Literature 95 7 The Media and Cinema 121 8 The Performing Arts 137 9 Painting 151 10 Architecture 171 Bibliography 185 Index 189 Preface most americans have heard of Australia, but very few could say much about it. -

KAVHA, Is an Outstanding National Heritage Place As a Convict Settlement Spanning the Era of Convict Transportation to Eastern Australia Between 1788-1855

Australian Heritage Database Places for Decision Class : Historic Identification List: National Heritage List Name of Place: Kingston and Arthurs Vale Historic Area Other Names: Place ID: 105962 File No: 9/00/001/0036 Nomination Date: 01/12/2006 Principal Group: Law and Enforcement Status Legal Status: 01/12/2006 - Nominated place Admin Status: 05/12/2006 - Under assessment by AHC--Australian place Assessment Recommendation: Place meets one or more NHL criteria Assessor's Comments: Other Assessments: : Location Nearest Town: Kingston Distance from town (km): Direction from town: Area (ha): 250 Address: Quality Row, Kingston, EXT 2899 LGA: Norfolk Island Area EXT Location/Boundaries: About 250ha, at Kingston, being an area bounded by a line commencing at the High Water Mark approximately 120m to the south east of Bloody Bridge, then proceeding westerly via the High Water Mark to about 230m west of the eastern boundary of Block 91a, then from high water level following the watershed boundary along the ridge west of Watermill Creek up to the 90m contour, then north-westerly via that contour to the boundary of Block 176, then following the western and northern boundary of Block 176 or the 90m ASL (whichever is the lower) to the north west corner of Block 52r, then via the northern boundary of Block 52r and its prolongation across Taylors Road to the western boundary of Block 79a, then northerly and easterly via the western and northern boundary of Block 79a to its intersection with the 90m ASL, then easterly via the 90m ASL to its intersection -

PR8022 C5B3 1984.Pdf

'PR C60d.a.. •CS�� lq81t- � '"' �r,;,�{ cJ c::_,.:;;J ; �· .;:,'t\� -- -- - - -- -2-fT7UU \�1\\�l\1�\\�1\l�l\\\\\ I 930171 3\ �.\ 3 4067 00 4 ' PR8022. C5B3198 D e CENG __ - Qv1.1T'n on Pn-oU.t::t!. C 5831984 MAIN GEN 04/04/85 THE UNIVERSI'IY OF QUEENSlAND LIBRARIES Death Is A Good Solution THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND PRESS SCHOLARS' LIBRARY Death Is A Good Solution The Convict Experience in Early Australia A.W. Baker University of Queensland Press First published 1984 by University of Queensland Press Box 42, St Lucia, Queensland, AustraW. ©A.W.Bakerl984 This book is copyright. Aput &om my fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisher. Typeset by University of Queensland Press Printed in Hong Kong by Silex Enterprise & Printing Co. Distributed in the UK, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and the Caribbe1n by Prentice Hall International, International Book DistnOutors Ltd, 66 Wood Lane End, Heme! Hempstead, Herts., England Distributed in the USA and Canada by Technical lmpex Corporation, 5 South Union Street, Lawrence, Mass. 01843 USA Cataloauing ia Publication Data Nt�tiorralLibraryoJAustrtJ!ia Baker, A.W. (Anthony William), 1936- Death is a good solution. Bibliography. .. ---· ---- ��· -�No -L' oRAR'V Includes index. � OF C\ :��,t;�,�k'f· I. Aumalim litera�- History mdl>AAI�. � �· 2. Convicts in literature. I. Title (Series: University of Queensland Press scholars' library). A820.9'3520692 LibrtJryofCortgrtss Baker, A.W.(Anthony William), 1936- Death is a good solution. -

The Camera, the Convict and the Criminal Life1

1 ‘Through a Glass, Darkly’: the Camera, the Convict and the Criminal Life1 Julia Christabel Clark B.A. (Hons.) Thomas Fleming Taken at Port Arthur 1873-4 Photographer: probably A.H. Boyd Queen Victoria Museum & Art Gallery Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) University of Tasmania November 2015 1 ‘For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.’ 1 Corinthians 13:12, King James Bible. 2 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Julia C. Clark, 14 November 2015 3 ABSTRACT A unique series of convict portraits was created at Tasmania’s Port Arthur penal station in 1873 and 1874. While these photographs are often reproduced, their author remained unidentified, their purpose unknown. The lives of their subjects also remained unexamined. This study used government records, contemporary newspaper reportage, convict memoirs, historical research and modern criminological theory to identify the photographer, to discover the purpose and use of his work, and to develop an understanding of the criminal careers of these men. -

Deconstructing and Reconstructing the Martin Cash/James Lester Burke

___________________________________________________________ DECONSTRUCTING AND RECONSTRUCTING THE MARTIN CASH/JAMES LESTER BURKE NARRATIVE/MANUSCRIPT OF 1870 Duane Helmer Emberg BA, BD, M Divinity, MA Communications Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2011 School of History and Classics The University of Tasmania Australia ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work began in the Archives of the State Library in Hobart, Tasmania, approximately twenty-one years ago when my wife, Joan, and I discovered a large bundle of foolscap pages. They were thick with dust, neatly bound and tied with a black ribbon. I mused, ‗perhaps this is it!' Excitement mounted as we turned to Folio 1 of the faded, Victorian handwritten manuscript. Discovered was the original 1870 narrative/manuscript of bushranger Martin Cash as produced by himself and scribe/co-author, James Lester Burke. The State Archives personnel assisted in reproducing the 550 pages. They were wonderfully helpful. I wish I could remember all their names. Tony Marshall‘s help stands out. A study of the original manuscript and a careful perusal of the many editions of the Cash adventure tale alerted me that the Cash/Burke narrative/manuscript had not been fully examined before, as the twelve 1880-1981 editions of Martin Cash, His Adventures…had omitted 62,501 words which had not been published after the 1870 edition. My twenty years of study is here presented and, certainly, it would not have happened without the help of many. Geoff Stillwell (deceased) pointed me in the direction of the possible resting place of the manuscript. The most important person to help in this production was Joan. -

Bushrangers in the Novel

DINGO (MANUSCRIPT) AND GENTLEMEN AT HEART: BUSHRANGERS IN THE NOVEL Submitted by Aidan Windle BA (Hons), Deakin University Grad. Dip. Ed., The University of Melbourne A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Communication, Arts and Critical Enquiry Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences La Trobe University Bundoora, Victoria 3086 Australia December 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… v Statement of Authorship………………………………………………………………………………………….. vi Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................... vii Dingo (Manuscript)…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Gentlemen at Heart: Bushrangers in the Novel (Dissertation) Preface……………………………………………………………………………………………… 257 Chapter One ........................................................................................... 262 Chapter Two........................................................................................... 283 Chapter Three......................................................................................... 301 Chapter Four........................................................................................... 325 Famous Last Words................................................................................. 347 Appendices Appendix A: Untitled Verse, Van Diemen’s Land, 1825 ....................... 353 Appendix B: The First Century of Bushranger Literature..................... -

Tony Robinson Explores Australia Is a Documentary Series

A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER & FIONA EDWARDS http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN-13-978-1-74295-058-7 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au A STUDY GUIDE OVERVIEW Tony Robinson, who has previously presented Time Team and Ned Kelly Uncovered, embarks on a case study of Australia’s past, from the earliest explorers to white settlement, Indigenous Australians, multiculturalism and Australia’s role in two world wars. Filmed on location around the country in November and December 2010, in this exciting and fast-paced six-part series Robinson is joined on his mammoth journey by some of Australia’s foremost historians and writers, including Tim Flannery, Thomas Keneally and Eric Wilmott. From the search to identify the ‘great southern land’, through colonial trials and tribulations and right up to the establishment of the dynamic modern Australia, Tony Robinson covers a huge amount of ground as he reveals the key events and major influences that define Australia – and Australians – today. SCREEN EDUCATION © ATOM 2 • Discuss the pros and cons of both television and film. Look at the following link. View the excerpts provided. http://listverse.com/2007/12/04/ top-10-greatest-tv-documentary-series/ • History of Medicine: thirteen parts, shown in 1978 on the BBC and on PBS stations in America. Jonathan Miller, in the series, used a combina- tion of visual images and lecture-like presentations to not only trace the history of medicine, but to explain the working of the human body in entertaining ways. • Victory at Sea: One of the earliest tel- evision documentary series and one of the first dealing with World War Two, Victory at Sea used extensive archival footage – up to that point unseen by the public – taken during the war to illustrate the long naval struggle that helped bring Allied vic- tory, from the Battle of the Atlantic to the island-hopping campaigns in the Pacific. -

The Canberra Region, Like Much of New South Wales, Was Largely Developed by Convicted Criminals, Known As Convicts

Convicts, Bolters and Bushrangers The Canberra region, like much of New South Wales, was largely developed by convicted criminals, known as convicts. In the 1820s and 1830s, when pastoralists were first establishing land holdings in the region, convicts were assigned to work as labourers on their properties. They cleared the land, tended the livestock and constructed roads and buildings. Whether driven to escape by harsh treatment from their masters, or simply by the desire for liberty, some convicts chose to take to the bush. These ‘bolters’ stole food, clothing, horses and guns from settlers and travellers to survive at large. From the 1850s onwards, after gold was discovered in NSW, the bushrangers, who were largely native-born men, held up travellers, local landowners and coaches transporting gold and cash. As one of the most isolated regions of nineteenth-century Australian settlement, the Canberra region had its fair share of bushrangers. In 1829, the Sydney Gazette and NSW Advertiser reported that in the county of Argyle ‘bushrangers [were] robbing and plundering in the most audacious manner’. The convicts and bushrangers featured here are just a few of the many who left their mark on the history of the Canberra region. Garrett Cotter (1802 – 86) Garrett Cotter was transported to Australia from Ireland at the age of nineteen. His crime was firing on British troops during an uprising, for which he was sentenced to be transported for life. Cotter was described by his employers as a good stockman and was eventually assigned to Francis Kenny’s property on the eastern side of Lake George. -

Cutting out and Taking Liberties: Australia's Convict Pirates, 1790

IRSH 58 (2013), Special Issue, pp. 197–227 doi:10.1017/S0020859013000278 r 2013 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Cutting Out and Taking Liberties: Australia’s Convict Pirates, 1790–1829 I AN D UFFIELD Honorary Fellow, University of Edinburgh 19/3F2 Dundas Street, Edinburgh EH3 6QG, UK E-mail: Ian.Duffi[email protected] ABSTRACT: The 104 identified piratical incidents in Australian waters between 1790 and 1829 indicate a neglected but substantial and historically significant resistance practice, not a scattering of unrelated spontaneous bolts by ships of fools. The pirates’ ideologies, cultural baggage, techniques, and motivations are identified, interrogated, and interpreted. So are the connections between convict piracy and bushranging; how piracy affected colonial state power and private interests; and piracy’s relationship to ‘‘age of revolution’’ ultra-radicalism elsewhere. HIDDEN HISTORY Transported convicts piratically seized at least eighty-two ships, vessels, and boats in Australian waters between 1790 and 1829. Unsuccessful piratical ventures involved at least twenty-two more. Somewhat more episodes occurred from 1830 to 1859,1 but until the 2000s this extensive phenomenon remained unrecognized among academic Australianists2 and 1. See Tables 1–7. Their data are drawn from my research, identifying 172 incidents, 1790–1859. Graeme Broxam has generously given me a draft of his forthcoming book on convict piracies. It identifies 39 incidents previously unknown to me – hence a current 1790–1859 total of 211. I do not discuss the incidents I know of only through Broxam. 2. For the exclusion of convict pirates, see Alan Atkinson, The Europeans in Australia, I and II (Oxford [etc.], 1997, 2004); Manning Clark, A History of Australia, I and II (Carlton, 1962, 1968); Grace Karskens, The Rocks: Life in Early Sydney (Carlton, 1997).