The Trickster and Queen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Will Rock You”

“We Will Rock You” By Queen and Ben Elton At the Hippodrome Theatre through October 20 By Princess Appau WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS When one walks into the Hippodrome Theatre to view “We Will Rock You,” the common expectation is a compilation of classic rock and roll music held together by a simple plot. This jukebox musical, however, surpasses those expectations by entwining a powerful plot with clever updating of the original 2002 musical by Queen and Ben Elton. The playwright Elton has surrounded Queen’s songs with a plot that highlights the familiar conflict of our era: youths being sycophants to technology. This comic method is not only the key to the show’s success but also the antidote to any fear that the future could become this. The futuristic storyline is connected to many of Queen’s lyrics that foreshadow the youthful infatuation with technology and the monotonous lifestyle that results. This approach is emphasized by the use of a projector displaying programmed visuals of a futuristic setting throughout the show. The opening scene transitions into the Queen song “Radio Gaga,” which further affirms this theme. The scene includes a large projection of hundreds of youth, clones to the cast performing on stage. The human cast and virtual cast are clothed alike in identical white tops and shorts or skirts; they sing and dance in sublime unison, defining the setting of the show and foreshadowing the plot. Unlike most jukebox musicals the plot is not a biographical story of the performers whose music is featured. “We Will Rock You” is set 300 years in the future on the iPlanet when individuality and creativity are shunned and conformity reigns. -

Brian May Plays “God Save the Queen” from the Roof of Buckingham Palace to Commemorate Queen Elizabeth II’S Golden Jubilee on June 3, 2002

Exclusive interview Brian May plays “God Save the Queen” from the roof of Buckingham Palace to commemorate Queen Elizabeth II’s Golden Jubilee on June 3, 2002. © 2002 Arthur Edwards 26 Astronomy • September 2012 As a teenager, Brian Harold May was shy, uncer- tain, insecure. “I used to think, ‘My God, I don’t know what to do, I don’t know what to wear, I don’t know who I am,’ ” he says. For a kid who didn’t know who he was or what he wanted, he had quite a future in store. Deep, abiding interests and worldwide success A life in would come on several levels, from both science and music. Like all teenagers beset by angst, it was just a matter of sorting it all out. Skiffle, stars, and 3-D A postwar baby, Brian May was born July 19, 1947. In his boyhood home on Walsham Road in Feltham on the western side of Lon- science don, England, he was an only child, the offspring of Harold, an electronics engineer and senior draftsman at the Ministry of Avia- tion, and Ruth. (Harold had served as a radio operator during World War II.) The seeds for all of May’s enduring interests came early: At age 6, Brian learned a few chords on the ukulele from his father, who was a music enthusiast. A year later, he awoke one morning to find a “Spanish guitar hanging off the end of my bed.” and At age 7, he commenced piano lessons and began playing guitar with enthusiasm, and his father’s engineering genius came in handy to fix up and repair equipment, as the family had what some called a modest income. -

Bakalářská Práce 2012

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at University of West Bohemia Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalářská práce 2016 Martina Veverková Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalářská práce THE ROCK BAND QUEEN AS A FORMATIVE FORCE Martina Veverková Plzeň 2016 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Studijní program Filologie Studijní obor Cizí jazyky pro komerční praxi Kombinace angličtina – němčina Bakalářská práce THE ROCK BAND QUEEN AS A FORMATIVE FORCE Vedoucí práce: Mgr. et Mgr. Jana Kašparová Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Fakulta filozofická Západočeské univerzity v Plzni Plzeň 2016 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci zpracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. Plzeň, duben 2016 ……………………… I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. et Mgr. Jana Kašparová for her advice which have helped me to complete this thesis I would also like to thank my friend David Růžička for his support and help. Table of content 1 Introduction ...................................................................... 1 2 The Evolution of Queen ................................................... 2 2.1 Band Members ............................................................................. 3 2.1.1 Brian Harold May .................................................................... 3 2.1.2 Roger Meddows Taylor .......................................................... 4 2.1.3 Freddie Mercury -

Queen Medley Projector Lyrics ADELAIDE

QUEEN MEDLEY ALL PARTS: All we hear is radio ga ga Radio goo goo Radio ga ga I want to break free I want to break free I want to break free from your lies You're so self satisfied I don't need you I've got to break free God knows, God knows I want to break free It's strange but it's true I can't get over the way you love me like you do But I have to be sure When I walk out that door Oh how I want to be free, Oh how I want to be free Oh how I want to break free Part 2 PART 1 & 3 I work hard (he works hard) every day of my life I work till I ache in my bones At the end (at the end of the day) I take home my hard earned pay all on my own I get down (down) on my knees (knees) And I start to pray Till the tears run down from my eyes (AHHHHH ) Lord somebody (somebody), ooh somebody (somebody), can anybody ALL PARTS: find me Par2: somebody All Parts: to love? Part 2: Part 1 & 3 somebody (somebody), somebody (somebody), can anybody ALL PARTS: find me, somebody tooooooooooo……… Buddy you're a boy make a big noise Playin' in the street gonna be a big man some day You got mud on yo' face You big disgrace Kickin' your can all over the place We will we will rock you We will we will rock you Buddy you're a young man hard man Shouting in the street gonna take on the world some day You got blood on yo' face You big disgrace Wavin' your banner all over the place We will we will rock you We will we will rock you We will we will rock you We will we will rock you . -

Rishi Malhotra

TCNJ JOURNAL OF STUDENT SCHOLARSHIP VOLUME XIV APRIL 2012 HETEROSEXUAL ANDROGYNY, QUEER HYPERMASCULINITY, AND HETERONORMATIVE INFLUENCE IN THE MUSIC OF FREDDIE MERCURY AND QUEEN Author: Rishi Malhotra Faculty Sponsor: Wayne Heisler, Department of Music ABSTRACT AND INTRODUCTION In a musical career that spanned two decades, Freddie Mercury served as lead vocalist and chief songwriter for the rock band, Queen. Initially regarded as a glam-metal outfit, they later experimented with more eclectic musical styles, notably the rock-opera fusion that characterized Mercury‟s widely successful composition, “Bohemian Rhapsody.” Mercury‟s use of imagery in live performances and music videos helped to shape responses to his lyrics and music. His change in appearance from androgynous, heterosexual rock star to “gay macho clone” led many to speculate that he was homosexual, although he never disclosed his orientation until shortly before his death. His protean appearance contrasted with his lyrical and musical consistency and provided alternative avenues for interpreting his music beyond the scope of heteronormativity. Many songs that were initially construed as reflecting his assumed heterosexuality were later interpreted as expressions of his homosexuality. Mercury has retained a legacy amongst admirers of differing sexual orientations, from members of the gay community during the early years of the AIDS epidemic to sports fans in stadiums around the world. Heteronormativity, according to Judith Butler, assumes heterosexuality as the norm, and deviation from heterosexuality as unnatural or abnormal. The apparent tendency to avoid decentralization of sexual identities and to default to heteronormative viewpoints is evident in the rock and pop music of Freddie Mercury and Queen. -

Pink Floyd - Dark Side of the Moon Speak to Me Breathe on the Run Time the Great Gig in the Sky Money Us and Them Any Colour You Like Brain Damage Eclipse

Pink Floyd - Dark Side of the Moon Speak to Me Breathe On the Run Time The Great Gig in the Sky Money Us and Them Any Colour You Like Brain Damage Eclipse Pink Floyd – The Wall In the Flesh The Thin Ice Another Brick in the Wall (Part 1) The Happiest Days of our Lives Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2) Mother Goodbye Blue Sky Empty Spaces Young Lust Another Brick in the Wall (Part 3) Hey You Comfortably Numb Stop The Trial Run Like Hell Laser Queen Bicycle Race Don't Stop Me Now Another One Bites The Dust I Want To Break Free Under Pressure Killer Queen Bohemian Rhapsody Radio Gaga Princes Of The Universe The Show Must Go On 1 Laser Rush 2112 I. Overture II. The Temples of Syrinx III. Discovery IV. Presentation V. Oracle: The Dream VI. Soliloquy VII. Grand Finale A Passage to Bangkok The Twilight Zone Lessons Tears Something for Nothing Laser Radiohead Airbag The Bends You – DG High and Dry Packt like Sardine in a Crushd Tin Box Pyramid song Karma Police The National Anthem Paranoid Android Idioteque Laser Genesis Turn It On Again Invisible Touch Sledgehammer Tonight, Tonight, Tonight Land Of Confusion Mama Sussudio Follow You, Follow Me In The Air Tonight Abacab 2 Laser Zeppelin Song Remains the Same Over the Hills, and Far Away Good Times, Bad Times Immigrant Song No Quarter Black Dog Livin’, Lovin’ Maid Kashmir Stairway to Heaven Whole Lotta Love Rock - n - Roll Laser Green Day Welcome to Paradise She Longview Good Riddance Brainstew Jaded Minority Holiday BLVD of Broken Dreams American Idiot Laser U2 Where the Streets Have No Name I Will Follow Beautiful Day Sunday, Bloody Sunday October The Fly Mysterious Ways Pride (In the Name of Love) Zoo Station With or Without You Desire New Year’s Day 3 Laser Metallica For Whom the Bell Tolls Ain’t My Bitch One Fuel Nothing Else Matters Master of Puppets Unforgiven II Sad But True Enter Sandman Laser Beatles Magical Mystery Tour I Wanna Hold Your Hand Twist and Shout A Hard Day’s Night Nowhere Man Help! Yesterday Octopus’ Garden Revolution Sgt. -

Queen Medley

I work hard (he works hard) every day of my life I work till I ache my bones The Online Choir At the end (at the end of the day) I take home my hard earned pay all on my own Throwback Thursdays I get down on my knees, ‘n’ I start to pray Till the tears run down from my eyes Lord Queen medley Somebody, somebody, somebody, somebody Can anybody find me, somebody to love? I see a little silhouetto of a man, Guitar Solo Scaramouche, Scaramouche, will you do the Fandango. Thunderbolt and lightning, very very Ooh, somebody, somebody, somebody, somebody frightening me. Can anybody find me, somebody to love? Galileo Galileo Galileo Galileo, Galileo figaro Magnifico Buddy you’re a boy make a big noise Playin’ in the street gonna be a big man some day I'm just a poor boy and nobody loves me You got mud on yo’ face, You big disgrace He's just a poor boy from a poor family, Kickin’ your can all over the place singin’ Spare him his life from this monstrosity We will we will rock you. We will we will rock you Easy come, easy go, will you let me go Buddy you’re a young man hard man Bismillah! No, we will not let you go Shoutin’ in the street gonna take on the world some day Let him go! Bismillah! We will not let you go You got blood on yo’ face, you big disgrace Let him go! Bismillah! We will not let you go Wavin’ your banner all over the place, singin’ Let me go Will not let you go We will we will rock you, we will we will rock you Let me go Will not let you go Let me go (Ah) We will we will rock you, we will we will rock you No, no, no, no, no, no, -

Set List All the Time

QUEENIE – set list all the time 39’ - Words and music by Brian May A Kind Of Magic - Words and music by Roger Taylor A Winter's Tale - Words and music by Freddie Mercury Action This Day - Words and music by Roger Taylor Another One Bites The Dust - Words and music by John Deacon Back Chat - Words and music by John Deacon Bicycle Race - Words and music by Freddie Mercury Bohemian Rhapsody - Words and music by Freddie Mercury Breakthru - Words and music by Queen Brighton Rock (intro) - Words and music by Brian May Crazy Little Thing Called Love - Words and music by Freddie Mercury Death On Two Legs - Words and music by Freddie Mercury Don’t Stop Me Now - Words and music by Freddie Mercury Dragon Attack - Words and music by Brian May Fat Bottomed Girls - Words and music by Brian May Flash (intro) - Words and music by Brian May Friends Will Be Friends - Words and music by Freddie Mercury and John Deacon God Save The Queen (outro) - (traditional) Arranged by Brian May Guitar Solo - Arranged by Brian May Hammer To Fall - Words and music by Brian May Headlong - Words and music by Queen Heaven For Everyone - Words and music by Roger Taylor I Want It All - Words and music by Brian May I Want To Break Free - Words and music by John Deacon I Was Born To Love You - Words and music by Freddie Mercury I'm Going Slightly Mad - Words and music by Queen In The Lap Of The Gods...Revisited - Words and music by Freddie Mercury Innuendo - Words and music by Queen Is This The World We Created? - Words and music by Brian May It’s A Hard Life - Words and music -

THE OFFICIAL INTERNATIONAL QUEEN FAN CLUB Winter 2012

THE OFFICIAL INTERNATIONAL QUEEN FAN CLUB Winter 2012 Editorial Hi Everyone! NOTES FROM GREG BROOKS elcome to the Winter issue of the fan club magazine! As I write it‘s certainly winter QUEEN ARCHIVIST. of the montages covers an area of 12 feet across by 7 feet, Where, freezing cold, and one little snow so that’s 84 square feet of ‘Works’ memorabilia in this case shower shut the UK own, as usual! I hope you are all s I write, we are working on a new presentation - hence even a very large 5’ x 8’ poster seems relatively small warm and well if you are sharing our weather (or of the 1974 Rainbow concerts – possibly a in the mix, when in fact it’s a signifi cant size. worse!). And if you are enjoying sunshine and heat- A new edit of the November shows, distilling both I was really pleased with the 21 montages we shot, and waves... I‘m SO jealous! into one, and looking at the audio from the March concert though each one took hours to set up and shoot, I’m glad we It‘s been a great Queen fi lled year hasn‘t it?! With va- and seeing what we can do with that - as well as the limi- spent that kind of time on them because we were acutely rious CD and DVD releases, and the excellent live ted video from that night too. We are searching like mad aware we’d only get one chance to do this to this scale and shows! And for those in North America, the highly ac- for more footage from that night, since every fan I know detail. -

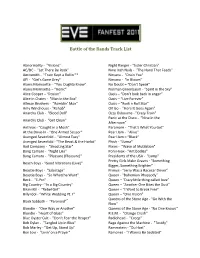

Battle of the Bands Track List

Battle of the Bands Track List Abnormality ‐ "Visions" Night Ranger ‐ "Sister Christian" AC/DC ‐ "Let There Be Rock" Nine Inch Nails ‐ "The Hand That Feeds" Aerosmith ‐ "Train Kept a Rollin'"* Nirvana ‐ "Drain You" AFI ‐ "Girl's Gone Grey" Nirvana ‐ "In Bloom" Alanis Morissette ‐ "You Oughta Know" No Doubt – “Don’t Speak” Alanis Morrisette – “Ironic” Norman Greenbaum ‐ "Spirit in the Sky" Alice Cooper – “Posion” Oasis – “Don’t look back in anger” Alice in Chains ‐ "Man in the Box" Oasis – “Live Forever” Allman Brothers ‐ "Ramblin' Man" Oasis – “Rock n Roll Star” Amy Winehouse ‐ "Rehab" OK Go ‐ "Here It Goes Again" Anarchy Club ‐ "Blood Doll" Ozzy Osbourne ‐ "Crazy Train" Panic at the Disco ‐ "Nine in the Anarchy Club ‐ "Get Clean" Afternoon" Anthrax ‐ "Caught in a Mosh" Paramore ‐ "That's What You Get" At the Drive‐In ‐ "One Armed Scissor" Pearl Jam ‐ "Alive" Avenged Sevenfold ‐ "Almost Easy" Pearl Jam – “Black” Avenged Sevenfold ‐ "The Beast & the Harlot" Phish ‐ "Llama" Bad Company ‐ "Shooting Star" Pixies ‐ "Wave of Mutilation" Bang Camaro ‐ "Night Lies" Poni Hoax ‐ "Antibodies" Bang Camaro ‐ "Pleasure (Pleasure)" Presidents of the USA ‐ "Lump" Pretty Girls Make Graves ‐ "Something Beach Boys ‐ "Good Vibrations (Live)" Bigger, Something Brighter" Beastie Boys ‐ "Sabotage" Primus ‐ "Jerry Was a Racecar Driver" Beastie Boys ‐ "So Whatcha Want" Queen ‐ "Bohemian Rhapsody" Beck ‐ "E‐Pro" Queen – ‘Crazy little thing called love” Big Country ‐ "In a Big Country" Queen – “Another One Bites the Dust” Bikini Kill ‐ "Rebel Girl" Queen – “I Want to Break Free” Billy Idol ‐ “White Wedding Pt. I" Queen – “One Vision” Queens of the Stone Age ‐ "Go With the Black Sabbath ‐ "Paranoid"* Flow" Blondie ‐ "One Way or Another" Queens of the Stone Age ‐ "No One Knows" Blondie ‐ "Heart of Glass" R.E.M. -

Cityfm Classic Rock Queen Top

1 BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY 2 WE WILL ROCK YOU 3 RADIO GA GA 4 ANOTHER ONE BITES THE DUST 5 DON'T STOP ME NOW 6 UNDER PRESSURE 7 SOMEBODY TO LOVE 8 I WANT TO BREAK FREE 9 CRAZY LITTLE THING CALLED LOVE 10 YOU'RE MY BEST FRIEND 11 A KIND OF MAGIC 12 WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS 13 LIVING ON MY OWN 14 BODY LANGUAGE 15 WHO WANTS TO LIVE FOREVER 16 BREAKTHRU 17 THE MARCH OF THE BLACK QUEEN 18 TIE YOUR MOTHER DOWN 19 FRIENDS WILL BE FRIENDS 20 I WAS BORN TO LOVE YOU 21 IS THIS THE WORLD WE CREATED... 22 ONE VISION 23 THE PROPHET'S SONG 24 FAT BOTTOMED GIRLS 25 THE MIRACLE 26 TOO MUCH LOVE WILL KILL YOU 27 '39 28 INNUENDO 29 LET ME LIVE 30 SHEER HEART ATTACK 31 HEAVEN FOR EVERYONE 32 I WANT IT ALL 33 BICYCLE RACE 34 THE GREAT PRETENDER 35 SON & DAUGHTER 36 BARCELONA 37 THE SHOW MUST GO ON 38 THESE ARE THE DAYS OF OUR LIVES 39 FLASH'S THEME 40 DREAMER'S BALL 41 KILLER QUEEN 42 YOU DON'T FOOL ME 43 IT'S A HARD LIFE 44 A WINTER'S TALE 45 HEADLONG 46 IT'S A BEAUTIFUL DAY 47 STONE COLD CRAZY 48 HAMMER TO FALL 49 I'M GOING SLIGHTLY MAD 50 FATHER TO SON 51 DRIVEN BY YOU 52 GOOD OLD-FASHIONED LOVER BOY 53 KEEP YOURSELF ALIVE 54 LEAVING HOME AIN'T EASY 55 MOTHER LOVE 56 ONE YEAR OF LOVE 57 RAIN MUST FALL 58 RIDE THE WILD WIND 59 IF YOU CAN'T BEAT THEM 60 THE INVISIBLE MAN (12' VERSION) 61 BACK CHAT 62 COOL CAT 63 DANCER 64 DOING ALL RIGHT 65 LOVE OF MY LIFE 66 PUT OUT THE FIRE 67 LET ME ENTERTAIN YOU 68 MODERN TIMES ROCK 'N' ROLL 69 MY LIFE HAS BEEN SAVED 70 ALL GOD'S PEOPLE 71 SAVE ME 72 SWEET LADY 73 ACTION THIS DAY 74 PUT OUT THE FIRE.MP3 75 DON'T LOSE YOUR HEAD 76 FOREVER 77 IN ONLY SEVEN DAYS 78 MADE IN HEAVEN 79 PLAY THE GAME 80 I CAN'T LIVE WITH YOU 81 SEASIDE RENDEZVOUS 82 GIMME THE PRIZE 83 GOOD COMPANY 84 LONG AWAY 85 MUSTAPHA 86 MY FAIRY KING 87 PRINCES OF THE UNIVERSE 88 PROCESSION 89 SOME DAY ONE DAY 90 STAYING POWER.MP3 91 THE LOSER IN THE END 92 FIGHT FROM THE INSIDE 93 GET DOWN, MAKE LOVE 94 LAZING ON A SUNDAY AFTERNOON 95 LIAR 96 OGRE BATTLE 97 SLEEPING ON THE SIDEWALK 98 MAN ON THE PROWL 99 PAIN IS SO CLOSE TO PLEASURE 100 WHITE QUEEN (AS IT BEGAN). -

Im Auftrag: Medienagentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 01805 - 060347 90476 [email protected]

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 01805 - 060347 90476 [email protected] QUEEN: NEUAUFLAGEN DER LETZTEN FÜNF ALBEN ERSCHEINEN AM 02. SEPTEMBER 2011 The Works, A Kind Of Magic, The Miracle, Innuendo Made in Heaven THE WORKS 2011 Remaster 00602527717623 Deluxe Edition 2011 Remaster 00602527717661 2011 Remaster - iTunes LP 00602527799650 TRACKLISTING Radio Ga Ga Tear It Up It's A Hard Life Man On The Prowl Machines (Back To Humans) I Want To Break Free Keep Passing The Open Windows Hammer To Fall Is This The World We Created...? BONUS EP I Go Crazy (B-Side) [Brian May] I Want To Break Free (Single Remix) [John Deacon] Hammer To Fall (Headbanger’s Mix) [Brian May] Is This The World We Created…? (Live in Rio, January 1985) [Freddie Mercury & Brian May] It's A Hard Life (Live in Rio, January 1985) [Freddie Mercury] Thank God It’s Christmas (Non-Album Single) [Roger Taylor & Brian May] A KIND OF MAGIC 2011 Remaster 00602527799711 Deluxe Edition 2011 Remaster 00602527799742 2011 Remaster - iTunes LP 00602527799803 TRACKLISTING One Vision A Kind Of Magic One Year Of Love Pain Is So Close To Pleasure Friends Will Be Friends Who Wants To Live Forever Gimme The Prize (Kurgan's Theme) Don't Lose Your Head Princes Of The Universe A Kind Of 'A Kind Of Magic' Friends Will Be Friends Forever BONUS EP A Kind Of Magic (Highlander Version) [Roger Taylor] One Vision (Single Version) [Queen] Pain Is So Close To Pleasure (Single Remix) [Freddie Mercury & John Deacon] Forever (Piano Version) [Brian May] A Kind Of Vision (Demo,