Rishi Malhotra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Killer Queen

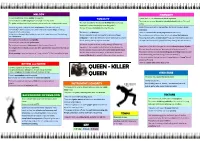

MELODY HARMONY The word setting is mainlysyllabic throughout TONALITY Queen liked to use adventurous chord sequences The melody has a wide range (goes very high and very low!) The song uses several altered or extended chords (such as 7ths and The main tonality for the piece is Eb Major (this is unusual The guitar solo borrows ideas from the chorus and verse sections of the song 11ths) because it’s a hard key to play in on the guitar!) The backing vocals use words and vocalisations (like oohs and aahs!) The key changes (modulates) during the song. Most of the chords are in root position, but there are some chord The melody is often conjunct, but with some wide angular leaps, including inversions. intervals of 6ths and octaves. The chorus is in Bb major There is a circle of 5ths chord progression in the chorus In the chorus the melody is harder to spot on it’s own because of the backing There are points where the tonality is not clear (“tonal The modulations to different keys are shown by perfect cadences vocal harmonies ambiguity”) - like in the first verse which starts with a C minor The song starts with a C minor chord—(you can’t tell that the piece is in The vocal part sometimes uses falsetto. chord, making the key signature unclear. Eb major until the chord is played half way through the verse—this is The vocal part also includes spoken text The vocal part contains a slide upwards (on the word “queen”) The chord sequences move quickly through different key Some parts of the chord sequence contain a faster harmonic rhythm The length of the melodic phrases are often uneven (like when the extra 6/8 bar signatures—for example in the first half of the chorus the (like one chord every beat on “guaranteed to blow your mind”) is added) chord sequence moves quickly through D minor and C major. -

RADIAL VELOCITIES in the ZODIACAL DUST CLOUD

A SURVEY OF RADIAL VELOCITIES in the ZODIACAL DUST CLOUD Brian Harold May Astrophysics Group Department of Physics Imperial College London Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy to Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine London · 2007 · 2 Abstract This thesis documents the building of a pressure-scanned Fabry-Perot Spectrometer, equipped with a photomultiplier and pulse-counting electronics, and its deployment at the Observatorio del Teide at Izaña in Tenerife, at an altitude of 7,700 feet (2567 m), for the purpose of recording high-resolution spectra of the Zodiacal Light. The aim was to achieve the first systematic mapping of the MgI absorption line in the Night Sky, as a function of position in heliocentric coordinates, covering especially the plane of the ecliptic, for a wide variety of elongations from the Sun. More than 250 scans of both morning and evening Zodiacal Light were obtained, in two observing periods – September-October 1971, and April 1972. The scans, as expected, showed profiles modified by components variously Doppler-shifted with respect to the unshifted shape seen in daylight. Unexpectedly, MgI emission was also discovered. These observations covered for the first time a span of elongations from 25º East, through 180º (the Gegenschein), to 27º West, and recorded average shifts of up to six tenths of an angstrom, corresponding to a maximum radial velocity relative to the Earth of about 40 km/s. The set of spectra obtained is in this thesis compared with predictions made from a number of different models of a dust cloud, assuming various distributions of dust density as a function of position and particle size, and differing assumptions about their speed and direction. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

We Will Rock You”

“We Will Rock You” By Queen and Ben Elton At the Hippodrome Theatre through October 20 By Princess Appau WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS When one walks into the Hippodrome Theatre to view “We Will Rock You,” the common expectation is a compilation of classic rock and roll music held together by a simple plot. This jukebox musical, however, surpasses those expectations by entwining a powerful plot with clever updating of the original 2002 musical by Queen and Ben Elton. The playwright Elton has surrounded Queen’s songs with a plot that highlights the familiar conflict of our era: youths being sycophants to technology. This comic method is not only the key to the show’s success but also the antidote to any fear that the future could become this. The futuristic storyline is connected to many of Queen’s lyrics that foreshadow the youthful infatuation with technology and the monotonous lifestyle that results. This approach is emphasized by the use of a projector displaying programmed visuals of a futuristic setting throughout the show. The opening scene transitions into the Queen song “Radio Gaga,” which further affirms this theme. The scene includes a large projection of hundreds of youth, clones to the cast performing on stage. The human cast and virtual cast are clothed alike in identical white tops and shorts or skirts; they sing and dance in sublime unison, defining the setting of the show and foreshadowing the plot. Unlike most jukebox musicals the plot is not a biographical story of the performers whose music is featured. “We Will Rock You” is set 300 years in the future on the iPlanet when individuality and creativity are shunned and conformity reigns. -

Top 5 Underrated Queen Songs Laura Ballinger Explores the Joys Of

Top 5 Underrated Queen Songs Laura Ballinger explores the joys of Queen’s lesser-known tracks Everyone knows the Queen classics, ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ and ‘Killer Queen’ to name just two. But what about those songs that are less well known and equally as good? Here’s a list of five of Queen’s most underrated songs, with the albums they feature on. 1. One Vision (A Kind of Magic) In top position comes ‘One Vision’. It starts with a slow motion, sci-fi sound, building into a funky beat and a classic Brian May guitar solo. The lyrics are memorable and catchy, with a fun back story as to why they became so iconic. When the band recorded this, they played around with the lyrics, finding alternative versions of ‘one vision’ which would fit the number of syllables. Some examples include, ‘John Deacon’, ‘One sex position’, then drifting into ones that didn’t quite fit, like ‘one shrimp’ and ‘one clam’. They actually settled on ‘fried chicken’ and, if you listen closely, it’s the final line in the song. Despite the comedic aspect, this song has quite a serious and meaningful undertone. It was written following Queen’s performance at Live Aid in 1985 and depicts the joining together of millions of people, united with the ‘one vision’ of making a better world for everyone. For this reason, it makes the top of the list. 2. Death on Two Legs (Dedicated To…) (A Night at the Opera) As one of Queen’s heavier songs, it’s not for everyone. -

MEDLEY Peter Buck, Michael Mills and Michael Stipe

Shinyg Happy People Words and Music by William Berry, MEDLEY Peter Buck, Michael Mills and Michael Stipe Shiny happy people laughing. WE WILL ROCK YOU (No wrong, no right, I’m gonna tell you there’s no black and no white. Buddy you’re a boy, make a big noise Meet me in the crowd, people, people. No blood, no stain. playing in the street, gonna be a big man someday, Throw your love around, love me, love me. All we need is) you got mud on your face, you big disgrace, Take it into town, happy, happy. one worldwide vision. kicking your can all over the place. Put it in the ground where the fowers grow. One fesh, one bone, one true religion. Gold and silver shine. We will, we will rock you! One voice, one hope, one real decision. We will, we will rock you! Gimme one night, gimme one hope. Shiny happy people holding hands. We will, we will rock you! Shiny happy people holding hands. We will, we will rock you! 1 2 Shiny happy people laughing Just gimme. Just gimme. CRAZY LITTLE THING CALLED LOVE One man, one bar, one day. One man, one night, hey, hey, Everyone around, love them, love them. Just gimme, Put it in your hands, take it, take it. This thing called love I just can’t handle it, There’s no time to cry, happy, happy. this thing called love I must get around to it, gimme, gimme, gimme fried chicken! Put it in your heart where tomorrow shines. -

2021 Cyclist Bible 2021 Cyclist

2021 CYCLIST BIBLE 39TH ANNUAL LOGAN, UTAH TO JACKSON HOLE, WYOMING BIKE RACE HOW IT ALL BEGAN The LoToJa was started in 1983 by two Logan cyclists, David Bern, a student at Utah State University, and Jeff Keller, the owner of Sunrise Cyclery. The two men wanted a race that resembled the difficulty of a one-day European classic, like Paris-Roubaix or the Tour of Flanders. LoToJa's first year featured seven cyclists racing 192 miles from Logan to a finish line in Jackson's town square. The winning time was just over nine hours by Logan cyclist, Bob VanSlyke. Since then, LoToJa has grown into one of the nation’s premier amateur cycling races and continues to be a grueling test of one's physical and mental stamina. Many compete to win their respective category, while others just ride to cross the finish line. At 200+ miles, LoToJa is the longest one-day USAC-sanctioned bicycle race in the country. Thank you for riding with us! Cover art courtesy of David V. Gonzales - davidvgonzalesart.com Photos provided by Snake River Photo - snakeriverphoto.com WELCOME TO LOTOJA INSIDE THIS GUIDE 1 — Event Schedule 15 — Crew Guidelines & Information 2 — Check-in/Packet Pickup 17 — Crew Vehicle Drive Distance Schedule 2 — Podium Awards & Protest Period 18 — Crew Driving Directions 3 — 2021 Start Schedule 19 — Cyclist Care / First-Aid Reminders 4 — Timing Chip, Finish Line, and Results 21 — Course Elevations and Map 5 — Cyclist Information 23 — Logan to Preston • Leg 1 Information 7 — Cyclist Guidelines 25 — Preston to Montpelier • Leg 2 Information 9 — Feed Zone Information 27 — Montpelier to Afton • Leg 3 Information 11 — Relay Team Guidelines 29 — Afton to Alpine • Leg 4 Information 12 — Additional Safety Guidelines 31 — Alpine to Finish • Leg 5 Information 13 — Veteran Advice 33 — King/Queen of Mtn. -

Freddie Mercury's Bicycle Race Turns Real 42 Years On

ANEESH PHADNIS RAM PRASAD SAHU SHINE JACOB ARUP ROYCHOUDHURY TAMAL BANDYOPADHYAY SUDIPTO DEY JOYDEEP GHOSH Freddie Mercury’s bicycle race turns real 42 years on ISHITA AYAN DUTT excitement around bicycles and you as gyms continue to remain shut. It’s Kolkata, 19 July are talking to a 57-year-old man,” COVID NO SPOKE good to see women also joining in,” said Pankaj M Munjal, chairman IN THE WHEEL FOR said a professional cyclist. Bicycle, bicycle, bicycle and managing director, Hero Motors The new entrants to the cycling I want to ride my bicycle, bicycle, Company (HMC). PEDAL PUSHERS arena are either gym goers trying to get bicycle... Hero has a 43 per cent share in the | Hero has seen 50% increase their dose of cardio, or people cooped 16-million Indian bicycle market. in demand for premium bicycles; up at home wanting to catch a breath Freddie Mercury of the British HMC plants are working overtime, demand for e-bikes shot up by of fresh air with some physical activity rock band Queen penned the song at about 110 per cent. “We are working almost 100% after lockdown thrown in. Either way, cycling just Bicycle Race in 1978 inspired by on Saturdays and Sundays,” he said. | Decathlon Sports India has seen got a fresh lease on life. Tour de France, the famed multiple Small wonder, given it had A spokesperson for Decathlon stage bicycling race. But 42 years later, orders for 500,000 bicycles in June, more than 45% cent year-on-year Sports India (DSI), the Indian arm of the Covid-19 pandemic has pushed compared to actual sales of 350,000 growth in sales in June and July the French sporting goods retailer, everyone into singing the same tune. -

Brian May Plays “God Save the Queen” from the Roof of Buckingham Palace to Commemorate Queen Elizabeth II’S Golden Jubilee on June 3, 2002

Exclusive interview Brian May plays “God Save the Queen” from the roof of Buckingham Palace to commemorate Queen Elizabeth II’s Golden Jubilee on June 3, 2002. © 2002 Arthur Edwards 26 Astronomy • September 2012 As a teenager, Brian Harold May was shy, uncer- tain, insecure. “I used to think, ‘My God, I don’t know what to do, I don’t know what to wear, I don’t know who I am,’ ” he says. For a kid who didn’t know who he was or what he wanted, he had quite a future in store. Deep, abiding interests and worldwide success A life in would come on several levels, from both science and music. Like all teenagers beset by angst, it was just a matter of sorting it all out. Skiffle, stars, and 3-D A postwar baby, Brian May was born July 19, 1947. In his boyhood home on Walsham Road in Feltham on the western side of Lon- science don, England, he was an only child, the offspring of Harold, an electronics engineer and senior draftsman at the Ministry of Avia- tion, and Ruth. (Harold had served as a radio operator during World War II.) The seeds for all of May’s enduring interests came early: At age 6, Brian learned a few chords on the ukulele from his father, who was a music enthusiast. A year later, he awoke one morning to find a “Spanish guitar hanging off the end of my bed.” and At age 7, he commenced piano lessons and began playing guitar with enthusiasm, and his father’s engineering genius came in handy to fix up and repair equipment, as the family had what some called a modest income. -

Queen 39 Live Killers Bass Transcription Sheet Music

Queen 39 Live Killers Bass Transcription Sheet Music Download queen 39 live killers bass transcription sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 2 pages partial preview of queen 39 live killers bass transcription sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 3939 times and last read at 2021-09-27 23:16:26. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of queen 39 live killers bass transcription you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Bass Guitar Tablature, Double Bass, Easy Piano Ensemble: Musical Ensemble Level: Beginning [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Queen Spread Your Wings Live Killers Accurate Bass Transcription Whit Tab Queen Spread Your Wings Live Killers Accurate Bass Transcription Whit Tab sheet music has been read 5215 times. Queen spread your wings live killers accurate bass transcription whit tab arrangement is for Early Intermediate level. The music notes has 3 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 08:45:45. [ Read More ] 39 Live Killers Queen John Deacon Complete And Accurate Bass Transcription Whit Tab 39 Live Killers Queen John Deacon Complete And Accurate Bass Transcription Whit Tab sheet music has been read 2960 times. 39 live killers queen john deacon complete and accurate bass transcription whit tab arrangement is for Beginning level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 16:50:19. [ Read More ] Queen John Deacon Dreamers Ball Live Killers Complete And Accurate Bass Transcription Whit Tab Queen John Deacon Dreamers Ball Live Killers Complete And Accurate Bass Transcription Whit Tab sheet music has been read 4720 times. -

'Killer Queen' (From the Album Sheer Heart Attack)

Queen: ‘Killer Queen’ (from the album Sheer Heart Attack) (For component 3: Appraising) Background information and performance circumstances ‘Killer Queen’ was written by Freddie Mercury and featured on Queen’s third studio album Sheer Heart Attack released in November 1974. Freddie Mercury was born Farrokh Bulsara on 5 September 1946 in Stone Town, Sultanate of Zanzibar (now Tanzania) and grew up in India, where he was educated at St Peter’s Boys School and took up the piano at the age of 7. At the age of 17 his family moved to Middlesex, England. Queen was formed in London in 1970 with singer Freddie Mercury, guitarist Brian May, drummer Roger Taylor and bassist John Deacon. Sheer Heart Attack and A Night at the Opera (1975) brought them international success. ‘Killer Queen’ was the first single from the album and it is one of the few songs where Freddie Mercury wrote the lyrics first, which are about an upper-class prostitute. ‘Killer Queen’ reached number 2 in the British charts and provided them with their first top 20 hit in the US, peaking at number 12 on the Billboard singles chart. The song won Freddie Mercury his first Ivor Novello Award. Performing forces and their handling The vocal part is performed by Freddie Mercury and is a high male voice – tenor. ‘Killer Queen’ uses lead and backing vocals, piano, overdubbed with a honky-tonk (jangle) piano, four electric guitars, bass guitar and drum kit. Guitars and vocals are overdubbed to create a richer colour. The guitars use techniques such as slides, bends, pull-offs and vibrato. -

Fat Bottomed Girls for Flute Quartet Or Flute Choir Sheet Music

Fat Bottomed Girls For Flute Quartet Or Flute Choir Sheet Music Download fat bottomed girls for flute quartet or flute choir sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of fat bottomed girls for flute quartet or flute choir sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 9673 times and last read at 2021-09-25 10:36:59. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of fat bottomed girls for flute quartet or flute choir you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Flute Ensemble: Flute Choir Level: Intermediate [ Read Sheet Music ] Other Sheet Music Fat Bottomed Girls Queen For Wind Quintet Drums Opt Fat Bottomed Girls Queen For Wind Quintet Drums Opt sheet music has been read 10115 times. Fat bottomed girls queen for wind quintet drums opt arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 22:46:43. [ Read More ] Fat Bottomed Girls For 8 Trombones Fat Bottomed Girls For 8 Trombones sheet music has been read 10934 times. Fat bottomed girls for 8 trombones arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-22 18:55:10. [ Read More ] Fat Bottomed Girls Fat Bottomed Girls sheet music has been read 13791 times. Fat bottomed girls arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 02:51:50.