B-El Sistema WILL 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Notes Anthony Mcgill, Clarinet Anna Polonsky, Piano

Program Notes Anthony McGill, clarinet Anna Polonsky, piano Brahms: Clarinet Sonata No. 2 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) was close to retiring when he heard a performance by clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld and was so deeply moved by his musical artistry that he deferred his retirement to compose four final works, all of which feature the clarinet in a starring role, including the two Clarinet Sonatas. The second sonata Opus 120, No. 2 in E-flat Major is made of up of four movements. The first movement is imbued with a sweetness that reflects Brahms’s own musical directions to the performers: Allegro amiable, a directive to play “…in a charming, gracious” manner. The second movement is a tour de force, marked “Apassionato, ma non troppo allegro” meaning with passion and features a Sostenuto middle section that is lyrical and dignified. The gentle third movement consists of a set of variations and is followed by a fourth movement defined by exuberance and joy. James Lee III: Ad Anah? James Lee III was born in Michigan in 1975. His major composition teachers include William Bolcom, Susan Botti and James Aikman. He was a composition fellow at Tanglewood Music Center in the summer of 2002, where he studied with Osvaldo Golijov and Kaija Saariaho. Mr. Lee’s works have been performed by orchestras including The National Symphony Orchestra, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. Dr. Lee, who earned a DMA in composition at the University of Michigan in 2005, is a Professor of Music at Morgan State University in Baltimore, Maryland. This beautiful composition, Ad Anah? means “How Long?” It is based on a Hebrew Prayer, and in the words of Anthony McGill before a recent performance, this short song reflects “…what we’re going through in this time…the struggle.” Clarinetist Anthony McGill serves as the principal clarinetist for the New York Philharmonic and serves on the faculty of the Juilliard School, the Curtis Institute of Music and Bard College Conservatory of Music. -

Anthony Mcgill 2019-20 Biography

ANTHONY MCGILL 2019-20 BIOGRAPHY Clarinetist Anthony McGill is one of classical music’s most recognizable and brilliantly multifaceted figures. He serves as the principal clarinet of the New York Philharmonic — that orchestra’s first African-American principal player — and maintains a dynamic international solo and chamber music career. Hailed for his “trademark brilliance, penetrating sound and rich character” (The New York Times), as well as for his “exquisite combination of technical refinement and expressive radiance” (The Baltimore Sun), McGill also serves as an ardent advocate for helping music education reach underserved communities and for addressing issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion in classical music. He was honored to take part in the inauguration of President Barack Obama, premiering a piece written for the occasion by John Williams and performing alongside violinist Itzhak Perlman, cellist Yo-Yo Ma, and pianist Gabriela Montero. McGill’s 2019-20 season includes the premiere of a new work by Tyshawn Sorey at the 92Y, and a special collaboration with mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato at Carnegie Hall. He will be a featured soloist at the Kennedy Center performing the Copland concerto at the SHIFT Festival of American Orchestras with the Jacksonville Symphony, and will also perform concertos by Copland, Mozart, and Danielpour with the Richmond, Delaware, Alabama, Reno, and San Antonio Symphonies. Additional collaborations include programs with Gloria Chien, Demarre McGill, Michael McHale, Anna Polonsky, Arnaud Sussman, and the Pacifica Quartet. McGill appears regularly as a soloist with top orchestras around North America including the New York Philharmonic, Metropolitan Opera, Baltimore Symphony, San Diego Symphony, and Kansas City Symphony. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Cara Mccool, Executive Director, MASNO 504.715.0818, [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Cara McCool, Executive Director, MASNO 504.715.0818, [email protected] Nocturne XIII Press Release September 27th, 2015, 5:00pm, Ritz-Carlton New Orleans The Musical Arts Society of New Orleans proudly announces acclaimed Venezuelan American pianist Gabriela Montero will be the featured performer at Nocturne XIII. MASNO’s annual fundraiser will be held on September 27th, 2015, 5:00pm, at the Ritz- Carlton New Orleans. This gala event is “black-tie preferred” and, as one of the area’s most anticipated musical evenings of the year, includes a champagne reception, salon recital by Gabriela Montero, and a fabulous dinner. Proceeds from the event help to fund MASNO’s wide variety of innovative, classical music programming during the year, including the New Orleans International Piano Competition, the New Orleans Piano Institute/Keyboard Festival, Salon Concert Events and Concerto Showcase in collaboration with the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra. Premium Sponsorship opportunities are still available. For details contact Executive Director Cara McCool at (504) 715-0818 or [email protected]. Event tickets are $200 per person or $2,000 for a table of ten, and may be purchased online at www.masno.org. Gabriela Montero Biography Montero’s visionary interpretations and unique improvisational gifts have won her a devoted following around the world. Anthony Tommasini remarked in The New York Times, "Montero's playing has everything: crackling rhythmic brio, subtle shadings, steely power in climactic moments, soulful lyricism in the ruminative passages and, best of all, unsentimental expressivity." Highlights from recent seasons include recitals at Avery Fisher Hall, Kennedy Center, Wigmore Hall, Vienna Konzerthaus, Berlin Philharmonie, Frankfurt Alte Oper, Cologne Philharmonie, Leipzig Gewandhaus, Munich Herkulessaal, Luxembourg Philharmonie, Lisbon Gulbenkian Museum, Tokyo Orchard Hall, and at the Edinburgh, Salzburg, Lucerne, Ravinia, Tanglewood, Saint-Denis, Dresden, Ruhr, Bergen, Istanbul, and Lugano festivals. -

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Artist Series: Anthony Mcgill Program

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Artist Series: Anthony McGill Program Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) “Abyss of the Birds” from Quatuor pour la fin du temps (Quartet for the End of Time) for Clarinet, Violin, Cello, and Piano (1940-41) Anthony McGill, clarinet Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) Sonata for Clarinet and Piano (1962) Allegro tristamente Romanza: Très calme Allegro con fuoco Anthony McGill, clarinet; Gloria Chien, piano Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Trio in A minor for Clarinet, Cello, and Piano, Op. 114 (1891) Allegro Adagio Andantino grazioso Allegro Anthony McGill, clarinet; Alisa Weilerstein, cello; Inon Barnatan, piano 2 Program Notes Program Notes By Laura Keller “Abyss of the Birds” from Quatuor pour la fin du temps (Quartet for the End of Time) for Clarinet, Violin, Cello, and Piano (1940-41) Olivier Messiaen (Avignon, 1908 – Paris, 1992) “The abyss is Time with its sadness, its weariness. The birds are the opposite of Time; they are our desire for light, for stars, for rainbows, and for jubilant songs.” -Messiaen Quartet for the End of Time had one of the most remarkable premieres of the 20th century. Messiaen served in the French army during World War II and was captured by the Germans at Verdun in June 1940. He was sent to Stalag VIII-A in Görlitz, Germany (today in Poland), where he was imprisoned during the winter of 1940-41. The prisoner-of-war camp was bitterly cold and food was in short supply, but Messiaen’s fame helped him greatly. A sympathetic guard provided him with the materials to compose this quartet and arranged the premiere on January 15, 1941 in a barely heated hall in front of a few hundred spellbound prisoners and guards. -

1 Series Salutes the American Composer and the American

August 16, 2010 Press contact: Erin Allen (202) 707-7302, [email protected] Public contact: Solomon Haile Selassie (202) 707-5347,[email protected] Website: www.loc.gov/rr/perform/concert CONCERTS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS ANNOUNCES 2010-2011 Anniversary Season Series Salutes the American Composer and the American Songbook The Library of Congress celebrates its 85 years of history as a concert presenter with a stellar 36-event season presenting new American music at the intersection of many genres–classical music, jazz, country, folk and pop. All concerts are presented free of charge in the Library’s historic, 500-seat Coolidge Auditorium. Tickets are available, for a nominal service charge only, through TicketMaster. Visit the Concerts from the Library of Congress websitefor detailed program and ticket information, at www.loc.gov/concerts. Honoring a longstanding commitment to American creativity and strong support for American composers, the series offers a springtime new music mini-festival, with world premiere performances of Library of Congress commissions by Sebastian Currier and Stephen Hartke. An impressive lineup of period instrument ensembles and artists, including Ensemble 415 and The English Concert, acknowledges the long history of the Coolidge Auditorium as a venue for early music. And the ever-expanding American Songbook is a major thematic inspiration throughout the year: among the many explorations are George Crumb’s sweeping song cycle of the same name, built on folk melodies, cowboy tunes, Appalachian ballads and African American spirituals; art songs from the Library’s Samuel Barber Collection; a new Songwriter’s Series collaboration with the Country Music Association; jazz improvisations on classics by George and Ira Gershwin; a Broadway cabaret evening–Irving Berlin to Kander & Ebb; and a lecture on the wellsprings of blues and the American popular song by scholar and cultural critic Greil Marcus. -

GABRIELA MONTERO Piano

GABRIELA MONTERO Piano Gabriela Montero’s visionary interpretations and unique compositional gifts have garnered her critical acclaim and a devoted following on the world stage. Anthony Tommasini remarked in The New York Times that “Montero’s playing had everything: crackling rhythmic brio, subtle shadings, steely power…soulful lyricism…unsentimental expressivity.” Recipient of the prestigious 2018 Heidelberger Frühling Music Prize and of the 4th International Beethoven Award, Montero’s recent and forthcoming highlights include debuts with the San Francisco Symphony (Edward Gardner), New World Symphony (Michael Tilson Thomas), Yomiuri Nippon Symphony in Tokyo (Aziz Shokhakimov), Orquesta de Valencia (Pablo Heras-Casado), and the Bournemouth Symphony (Carlos Miguel Prieto), the latter of which will feature her as Artist-in- Residence for the 2019-2020 season. Montero also recently performed her own “Latin” Concerto with the Orchestra of the Americas at the Hamburg Elbphilharmonie and Edinburgh Festival, as well as at Carnegie Hall and the New World Center with the NYO2. Additional highlights include a European tour with the City of Birmingham Symphony and Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla; a second tour with the cutting edge Scottish Ensemble, this time with Montero’s latest composition Babel as the centrepiece of the programme; her long-awaited return to Warsaw for the Chopin in Europe Festival, marking 23 years since her prize win at the International Chopin Piano Competition; and return invitations to work with Marin Alsop and the Baltimore Symphony, -

142093 Subscription Brochure-Rev2.Indd

San Francisco Symphony 2018–19 Season Join Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony for the 2018-19 Season. Subscribe now to guarantee your seats! A new, special offer just for subscribers. Get 2 additional DSH concerts free when you buy a Davies Symphony Hall 6 or 7-concert package. Get 3 additional DSH concerts free when you buy a Davies Symphony Hall 12-concert or more package. Act now! This limited-time offer ends April 30, 2018. Exclusions apply. facebook @sfsymphony FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHY: Brandon Patoc and Spencer Lowell ADDITIONAL PHOTOGRAPHY: Stefan Cohen and Kristen Loken ON THE COVER: Michael Tilson Thomas Music Director, Jacob Nissly Principal Percussion, Nadya Tichman Associate Concertmaster, Polina Sedukh Second Violin, In Sun Jang First Violin ON THE BACK COVER: Raushan Akhmedyarova Second Violin, Ed Stephan Principal Timpani, Paul Welcomer Second Trombone, Scott Pingel Principal Bass “Glorious music in a glorious city–there 01 Why Subscribe is nothing better!” Table of Season 02 Highlights Nadya Tichman / Associate Concertmaster 04 Film Series 05 Concerts Contents Subscription 15 Packages Great Performers 18 Packages Film Series 19 Packages Music 20 for Families Chamber 21 Music Organ 21 Concerts Youth 22 Orchestra Open 23 Rehearsals Amazing 24 Add-Ons 27 Seating 28 Prices ASSOCIATE CONCERTMASTER ASSOCIATE Season 29 at a Glance SFS Media NADYA TICHMAN, NADYA 34 volume Listen to music excerpts: sfsymphony.org Subscribe: 415-864-6000 sfsymphony.org 01 / “ One of the things I love most Why Why Subscribe about working with the San Francisco Symphony Subscribe is that we play music that As a Symphony subscriber, you move to the front of the line for fi rst pick of spectacular seats that are sure to go fast. -

2020-2021 Season Chronology of Events

Carnegie Hall 2020–2021 Season Chronological Listing of Events All performances take place at Carnegie Hall, 57th Street and Seventh Avenue, unless otherwise indicated. October CARNEGIE HALL'S Wednesday, October 7, 2020 at 7:00 PM OPENING NIGHT GALA Los Angeles Philharmonic LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC Gustavo Dudamel, Music and Artistic Director Stern Auditorium / Perelman Stage Lang Lang, Piano Liv Redpath, Soprano JOHN ADAMS Tromba Lontana EDVARD GRIEG Piano Concerto in A Minor, Op. 16 EDVARD GRIEG Selections from Peer Gynt DECODA Thursday, October 8, 2020 at 7:30 PM Weill Recital Hall Decoda LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Septet in E-flat Major, Op. 20 FRANZ SCHUBERT String Trio in B-flat Major, D. 471 GUSTAV MAHLER Selection from "Kräftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell" from Symphony No. 1 in D Major (arr. Decoda) ARNOLD SCHOENBERG Selections from Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31 (arr. Decoda) VARIOUS COMPOSERS Ode to Beethoven (World Premiere created in collaboration with the audience) LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC Thursday, October 8, 2020 at 8:00 PM Stern Auditorium / Perelman Stage Los Angeles Philharmonic Gustavo Dudamel, Music and Artistic Director Leila Josefowicz, Violin Gustavo Castillo, Narrator GABRIELLA SMITH Tumblebird Contrails (NY Premiere) ANDREW NORMAN Violin Concerto (NY Premiere, co-commissioned by Carnegie Hall) ALBERTO GINASTERA Estancia, Op. 8 Andrew Norman is holder of the 2020-2021 Richard and Barbara Debs Composer's Chair at Carnegie Hall. LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC Friday, October 9, 2020 at 8:00 PM Stern Auditorium / Perelman -

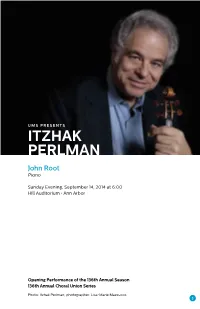

ITZHAK PERLMAN John Root Piano

UMS PRESENTS ITZHAK PERLMAN John Root Piano Sunday Evening, September 14, 2014 at 6:00 Hill Auditorium • Ann Arbor Opening Performance of the 136th Annual Season 136th Annual Choral Union Series Photo: Itzhak Perlman; photographer: Lisa-Marie Mazzucco. 3 UMS PROGRAM J. S. Bach Sonata for Violin and Keyboard in G Major, BWV 1019 Allegro Largo Allegro Adagio Allegro César Franck Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Major Allegretto ben moderato Allegro Recitativo — Fantasia Allegretto poco mosso INTERMISSION Maurice Ravel Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 2 in G Major FALL 2014 FALL Allegretto Blues: Moderato Perpetuum mobile: Allegro Additional works will be announced by Mr. Perlman. This evening’s performance is sponsored by KeyBank. This evening’s performance is supported by Drs. Max Wicha and Sheila Crowley, by Richard and Susan Gutow, and by Tom and Debby McMullen and McMullen Properties. Media partnership is provided by WGTE 91.3 FM and WRCJ 90.9 FM. The Steinway piano used in this evening’s recital is made possible by the William and Mary Palmer Endowment Fund. Special thanks to Tom Thompson of Tom Thompson Flowers, Ann Arbor, for his generous contribution of floral art for this evening’s recital. Mr. Perlman records for Sony Classical/Sony Music Entertainment; Warner Classics and Erato Classics/ Warner Music; Deutsche Grammophon and Decca/Universal Music Group; and Telarc. Mr. Perlman appears by arrangement with IMG Artists, LLC. ITZHAK PERLMAN 4 BE PRESENT NOW THAT YOU’RE IN YOUR SEAT… The sonatas of Franck and Ravel — two of the most beloved works in the French violin repertory — are a study in contrasts. -

ANTHONY Mcgill, Clarinet Recognized As One of the Classical

ANTHONY McGILL, clarinet Recognized as one of the classical music world’s finest solo, chamber and orchestral musicians, Anthony McGill was named Principal Clarinet of the New York Philharmonic beginning in September 2014. He previously served as Principal Clarinet of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Associate Principal Clarinet of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. McGill has appeared as soloist with many orchestras including the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, the American Symphony Orchestra and the New York String Orchestra, all at Carnegie Hall. In January of 2015 he performed and recorded the Nielsen Photo by David Finlayson Clarinet Concerto with the New York Philharmonic. Other orchestra performances have been with the Baltimore, Kansas City, Memphis, New Jersey and San Diego symphonies, as well as Orchestra 2001 and the Chicago Youth Symphony Orchestra. As a chamber musician McGill has performed throughout the United States, Europe, and Asia with the Brentano, Daedalus, Guarneri, Miro, Pacifica, Shanghai and Tokyo quartets and in 2015-16 will be with the Dover, JACK and Takacs quartets. He will tour with Musicians from Marlboro, performs under the auspices of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, and appears on such series as the Philadelphia Chamber Music Society and the University of Chicago Presents. Festival appearances include Tanglewood, Marlboro, Mainly Mozart, Music@Menlo, and Santa Fe, Seattle and Skaneateles chamber music festivals, to name a few. Anthony McGill has collaborated with Emanuel Ax, Yefim Bronfman, Gil Shaham, Midori, Mitsuko Uchida and Lang Lang, and on January 20, 2009, performed with Itzhak Perlman, Yo-Yo Ma and Gabriela Montero at the inauguration of President Barack Obama. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 155, Pt. 1 January 20, 2009 Court of the United States John Paul Ste- the Ways We Use Energy Strengthen Our Ad- Tories

1182 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 155, Pt. 1 January 20, 2009 Court of the United States John Paul Ste- the ways we use energy strengthen our ad- tories. And we will transform our schools vens, who will administer the oath of office versaries and threaten our planet. These are and colleges and universities to meet the de- to the Vice President-elect. Will you all the indicators of crisis, subject to data and mands of a new age. All this we can do. All please stand. statistics. Less measurable but no less pro- this we will do. Associate Justice JOHN PAUL STEVENS found is a sapping of confidence across our Now, there are some who question the administered to the Vice President-elect the land, a nagging fear that America’s decline scale of our ambitions, who suggest that our oath of office prescribed by the Constitution, is inevitable, that the next generation must system cannot tolerate too many big plans. which he repeated, as follows: lower its sights. Their memories are short. For they have for- ‘‘I, JOSEPH ROBINETTE BIDEN, JR. do Today I say to you that the challenges we gotten what this country has already done, solemnly swear that I will support and de- face are real. They are serious, and they are what free men and women can achieve when fend the Constitution of the United States many. They will not be met easily or in a imagination is joined to common purpose against all enemies foreign and domestic; short span of time. But know this, America— and necessity to courage. -

4-16 Montero Program

Williams College Department of Music Williamstown Jazz Festival with Opus 3 Artists Presents G A B R I E L A M O N T E R O Piano Johann Sebastian Bach Chaconne (From Partita No. 2 in D Minor (1685-1750) for Violin), BWV 1004 Arr. by F. Busoni Frederic Chopin Ballade No. 3 in A-flat Major, opus 47 (1810-1849) Alberto Ginastera Sonata No. 1, opus 22 (1916-1983) Allegro marcato Presto misterioso Adagio molto appassionato Ruvido ed ostinato ***intermission*** Improvisation on themes or pieces suggested by audience members (Please be prepared to sing the theme if Ms. Montero does not know the piece) Wednesday, April 16, 2008 8:00 P.M. The Clark Williamstown, Massachusetts Upcoming events: 4/18: Williams Chamber Choir, Williams College Museum of Art, 4:00 p.m. 4/18: Williams Percussion Ensemble, Chapin Hall, 8:00 p.m, 4/19: Junior Recital: Alicia Choi, violin, Brooks-Rogers, 3:00 p.m. 4/19: Williams Chamber Choir, Griffin 3, 5:00 p.m. 4/20: Artsbreak, The Clark, 1:00 p.m. 4/20: Maru A Pula, Chapin Hall, 3:00 p.m. 4/23: MIDWEEKMUSIC, Chapin Hall, 12:15 p.m. Please turn off or mute cell phones. No photography or recording is permitted. Tonight’s concert is also made possible in part by the following Friends of the Williamstown Jazz Festival*: The Crabtree Family Suzanne and David Kemple Robert B. Lee, M.D. Frank Ubile Jean F. Vankin Ann Vanneman in memory of Tom Mitchell * to find out how to become a friend of the Williamstown Jazz Festival, contact Artistic Director Andy Jaffe at: [email protected] “Ms Montero’s playing had everything: crackling rhythmic brio, subtle shadings, steely power in climactic moments, soulful lyricism in ruminative passages and, best of all, unsentimental expressivity.” - Anthony Tommasini, New York Times Gabriela Montero’s visionary interpretations and unique improvisational gift have won her a quickly expanding audience and devoted following around the world.