A Time for New Dreams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LA MUSICA D'avanguardia (Provenienza Sconosciuta

LA MUSICA D’AVANGUARDIA (provenienza sconosciuta!!) Presentazione Questo volume si propone di fornire una panoramica, la piu' aggiornata possibile, sui fenomeni musicali che esulano dalle correnti tradizionali del rock, del jazz e della classica, e che rappresentano in senso lato l'attuale "avanguardia". In tal senso l'avanguardia, piu' che un movimento monolitico e omogeneo, appare come una federazione piu' o meno aperta di tante scuole diverse e separate. Alcune costituiscono la cosiddetta "contemporanea" (capitoli 1-7), figlia dell'avanguardia classica; altre sono scaturite della sperimentazione dei complessi rock (capitoli 8-10); altre ancora appartengono al nuovo jazz, e non fanno altro che legittimare una volta per tutte il jazz nel novero della musica "intellettuale" (capitoli 11-13); la new age, infine, sfrutta le suggestioni delle scuole precedenti (capitoli 14-17). Piuttosto che un'introduzione generale ci sembra allora piu' opportuno fornire una presentazione capitolo per capitolo: 1. L'avanguardia popolare. Per avanguardia si intendeva un tempo soltanto l'avanguardia classica. A dimostrazione di come i tempi siano cambiati, questo libro e' in gran parte dedicato a musicisti che hanno le loro origini nel rock, nel jazz o nella new age. In questo primo capitolo ci proponiamo di fornire una panoramica storica sulla nascita dei movimenti musicali che hanno introdotto le novita' armoniche, acustiche, ideologiche su cui speculano tuttora gli sperimentatori moderni. Ci premeva anche trasmettere la sensazione che esista una qualche continuita' fra i lavori di Varese e Stockhausen (per citarne due particolarmente famosi) e i protagonisti di questo libro. 2. Minimalismo. La scuola minimalista degli anni Settanta era chiaramente delimitata. -

Stan Magazynu Caĺ†Oĺıäƒ Lp Cd Sacd Akcesoria.Xls

CENA WYKONAWCA/TYTUŁ BRUTTO NOŚNIK DOSTAWCA ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - AT FILLMORE EAST 159,99 SACD BERTUS ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - AT FILLMORE EAST (NUMBERED 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - BROTHERS AND SISTERS (NUMBE 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - EAT A PEACH (NUMBERED LIMIT 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - IDLEWILD SOUTH (GOLD CD) 129,99 CD GOLD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - THE ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND (N 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ASIA - ASIA 179,99 SACD BERTUS BAND - STAGE FRIGHT (HYBRID SACD) 89,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BAND, THE - MUSIC FROM BIG PINK (NUMBERED LIMITED 89,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BAND, THE - THE LAST WALTZ (NUMBERED LIMITED EDITI 179,99 2 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BASIE, COUNT - LIVE AT THE SANDS: BEFORE FRANK (N 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BIBB, ERIC - BLUES, BALLADS & WORK SONGS 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC - JUST LIKE LOVE 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC - RAINBOW PEOPLE 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC & NEEDED TIME - GOOD STUFF 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC & NEEDED TIME - SPIRIT & THE BLUES 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BLIND FAITH - BLIND FAITH 159,99 SACD BERTUS BOTTLENECK, JOHN - ALL AROUND MAN 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 CAMEL - RAIN DANCES 139,99 SHMCD BERTUS CAMEL - SNOW GOOSE 99,99 SHMCD BERTUS CARAVAN - IN THE LAND OF GREY AND PINK 159,99 SACD BERTUS CARS - HEARTBEAT CITY (NUMBERED LIMITED EDITION HY 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY CHARLES, RAY - THE GENIUS AFTER HOURS (NUMBERED LI 99,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY CHARLES, RAY - THE GENIUS OF RAY CHARLES (NUMBERED 129,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY -

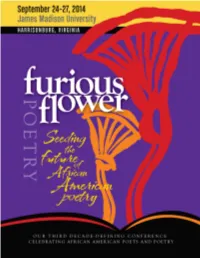

Furiousflower2014 Program.Pdf

Dedication “We are each other’s harvest; we are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond.” • GWENDOLYN BROOKS Dedicated to the memory of these poets whose spirit lives on: Ai Margaret Walker Alexander Maya Angelou Alvin Aubert Amiri Baraka Gwendolyn Brooks Lucille Clifton Wanda Coleman Jayne Cortez June Jordan Raymond Patterson Lorenzo Thomas Sherley Anne Williams And to Rita Dove, who has sharpened love in the service of myth. “Fact is, the invention of women under siege has been to sharpen love in the service of myth. If you can’t be free, be a mystery.” • RITA DOVE Program design by RobertMottDesigns.com GALLERY OPENING AND RECEPTION • DUKE HALL Events & Exhibits Special Time collapses as Nigerian artist Wole Lagunju merges images from the Victorian era with Yoruba Gelede to create intriguing paintings, and pop culture becomes bedfellows with archetypal imagery in his kaleidoscopic works. Such genre bending speaks to the notions of identity, gender, power, and difference. It also generates conversations about multicultur- alism, globalization, and transcultural ethos. Meet the artist and view the work during the Furious Flower reception at the Duke Hall Gallery on Wednesday, September 24 at 6 p.m. The exhibit is ongoing throughout the conference, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. FUSION: POETRY VOICED IN CHORAL SONG FORBES CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS Our opening night concert features solos by soprano Aurelia Williams and performances by the choirs of Morgan State University (Eric Conway, director) and James Madison University (Jo-Anne van der Vat-Chromy, director). In it, composer and pianist Randy Klein presents his original music based on the poetry of Margaret Walker, Michael Harper, and Yusef Komunyakaa. -

A Real Love Story Camila Batmanghelidjh, Founder of Kids Company, Talks About Neuroplasticity

MUSE.09/10/12 A Real Love Story Camila Batmanghelidjh, founder of Kids Company, talks about neuroplasticity The Pride of the North How Gay Pride in York is changing perceptions Freshers’ Week 1964 What the crazy kids of York were up to in the Sixties M2 www.ey.com/uk/careers 09/10/12 Muse. M10 M12 M22 Features. Arts. Film. M4. Flamboyant psychotherapist Camila Bat- M18. Mary O’Connor speaks to poet and rap- M22. James Tyas interviews Sally El Hosaini, manghelidjh speaks to Sophie Rose Walker per Kate Tempest about love and we look back Director of My Brother the Devil, premiering at about the work of her charity Kids Company. at the legacy of Gustav Klimt. the BFI’s London Film Festival this October. M6. What is the frankly rather cool history of Freshers at York? Bella Foxwell investigates Fashion. Food & Drink. what’s changed and what hasn’t. M16. Ben Burns interviews fashion illustra- M23. Ward off Freshers Flu with Hana Teraie- M8. Gay Pride is out and thriving in York. tor Richard Kilroy, Miranda Larbi goes crazy for Wood’s delicous Ratatouille and Irish Coffee. Stefan Roberts and Tom Witherow looks at jacquard, and the ‘Whip-ma-Whop-ma’ shoot on Plus our review of Jamie Oliver’s new restaurant. the Northern scene’s dynamic. M12. M10. Young girls in Sri Lanka are prime Music. Image Credits. targets for terrorism training. Laura Hughes investigates why. M20. Death-blues duo Wet Nuns talk to Ally Cover: Kate Treadwell, Kids Company Swadling about facial hair, and there are stories Photoshoot: All photos credit to the marvellous from Pale Seas. -

Table of Contents

1 •••I I Table of Contents Freebies! 3 Rock 55 New Spring Titles 3 R&B it Rap * Dance 59 Women's Spirituality * New Age 12 Gospel 60 Recovery 24 Blues 61 Women's Music *• Feminist Music 25 Jazz 62 Comedy 37 Classical 63 Ladyslipper Top 40 37 Spoken 65 African 38 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 "Mehn's Music' 70 Asian 39 Videos 72 Celtic * British Isles 40 Kids'Videos 76 European 43 Songbooks, Posters 77 Latin American _ 43 Jewelry, Books 78 Native American 44 Cards, T-Shirts 80 Jewish 46 Ordering Information 84 Reggae 47 Donor Discount Club 84 Country 48 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 49 Artist Index 86 Art exhibit at Horace Williams House spurs bride to change reception plans By Jennifer Brett FROM OUR "CONTROVERSIAL- SUffWriter COVER ARTIST, When Julie Wyne became engaged, she and her fiance planned to hold (heir SUDIE RAKUSIN wedding reception at the historic Horace Williams House on Rosemary Street. The Sabbats Series Notecards sOk But a controversial art exhibit dis A spectacular set of 8 color notecards^^ played in the house prompted Wyne to reproductions of original oil paintings by Sudie change her plans and move the Feb. IS Rakusin. Each personifies one Sabbat and holds the reception to the Siena Hotel. symbols, phase of the moon, the feeling of the season, The exhibit, by Hillsborough artist what is growing and being harvested...against a Sudie Rakusin, includes paintings of background color of the corresponding chakra. The 8 scantily clad and bare-breasted women. Sabbats are Winter Solstice, Candelmas, Spring "I have no problem with the gallery Equinox, Beltane/May Eve, Summer Solstice, showing the paintings," Wyne told The Lammas, Autumn Equinox, and Hallomas. -

African-American Writers

AFRICAN-AMERICAN WRITERS Philip Bader Note on Photos Many of the illustrations and photographs used in this book are old, historical images. The quality of the prints is not always up to current standards, as in some cases the originals are from old or poor-quality negatives or are damaged. The content of the illustrations, however, made their inclusion important despite problems in reproduction. African-American Writers Copyright © 2004 by Philip Bader All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bader, Philip, 1969– African-American writers / Philip Bader. p. cm.—(A to Z of African Americans) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes. ISBN 0-8160-4860-6 (acid-free paper) 1. American literature—African American authors—Bio-bibliography—Dictionaries. 2. African American authors—Biography—Dictionaries. 3. African Americans in literature—Dictionaries. 4. Authors, American—Biography—Dictionaries. I. Title. II. Series. PS153.N5B214 2004 810.9’96073’003—dc21 2003008699 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Joan M. -

An AZ of Merton's Black Heritage

An A-Z of Merton’s Black Heritage: Part Two. MUSIC: Merton musical associations. SLICK RICK ( real name Richard Walters. ) Of Jamaican heritage, Rick was born in Mitcham in 1965 and sadly blinded in one eye during childhood. In 1976 his family emigrated, settling in the Bronx district of New York. After studying at the Laguardia High School of Music & Art, Rick began rapping and beat-boxing as part of the Get Fresh Crew. Then known as MC Ricky D, Walters appeared alongside Doug E Fresh on “Top of the Pops” and “Soul Train,” performing their hit singles “The Show” and ”La Di Da Di.” In 1986 Rick joined the leading rap/hip-hop label Def Jam Records. His album The Great Adventures of Slick Rick” reached No. 1 in the Billboard R&B/Hip-hop chart. After a five year jail term for injuring his bodyguard cousin ( and a passer-by, ) who had been extorting money and threatening his family, Rick released a further two albums but these had mixed reviews. His fourth album “The Art of Storytelling” was released in 1999 to critical acclaim and featured collaborations with OutKast, Raekwon and Snoop Dog. He has also worked with Will.i.am. After reforming his behaviour, Rick was pardoned of former charges and given U S citizenship. He now mentors youngsters against violence and supports humanitarian charities. (Left ) Slick Rick pictured during the late 1980s and ( right ) performing in Los Angeles in 2009. YOUNG MC ( Real name Marvin Young ) A Hip-hop, rapper and producer, Marvin is the son of Jamaican immigrants and was born in South Wimbledon in May 1967. -

Traineeships

Traineeships Closing date: Monday 19th November 2018 Manchester International Festival (MIF) is an extraordinary 18-day festival, held every two years, that brings the best new music, art, theatre, dance and free events to places and spaces across Manchester. We’ve previously featured the likes of Sampha, The xx, FKA twigs, Björk, Levelz, Gorillaz and Bugzy Malone – and we’ve just announced that our 2019 Festival next summer will feature new and exclusive projects from Skepta, Idris Elba and Yoko Ono, among others. We’re looking for 30 people from Manchester to take part in a two-week creative industry training academy, where you’ll learn a variety of new skills. Five people from this group will then be selected to join our first ever Creative Traineeship Programme from January to August 2019, when you’ll be offered paid positions as we work towards putting on our next Festival in July. You don’t need any qualifications or experience to apply – and MIF Creative Trainees can earn money (living wage) while gaining valuable skills and experience in our fast-paced festival environment. Are you: • 19+ and register unemployed? • Interested in creativity and music • Proud of Manchester • Able to communicate with people well • Eager to learn new IT skills • Enthusiastic to start your career in the arts. • Positive, motivated and cooperative • Respectful of people from all backgrounds Experience offered as part of an MIF Traineeship Working with technical and arts professionals from many different organisations Providing general administrative -

Ambient Music the Complete Guide

Ambient music The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 05 Dec 2011 00:43:32 UTC Contents Articles Ambient music 1 Stylistic origins 9 20th-century classical music 9 Electronic music 17 Minimal music 39 Psychedelic rock 48 Krautrock 59 Space rock 64 New Age music 67 Typical instruments 71 Electronic musical instrument 71 Electroacoustic music 84 Folk instrument 90 Derivative forms 93 Ambient house 93 Lounge music 96 Chill-out music 99 Downtempo 101 Subgenres 103 Dark ambient 103 Drone music 105 Lowercase 115 Detroit techno 116 Fusion genres 122 Illbient 122 Psybient 124 Space music 128 Related topics and lists 138 List of ambient artists 138 List of electronic music genres 147 Furniture music 153 References Article Sources and Contributors 156 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 160 Article Licenses License 162 Ambient music 1 Ambient music Ambient music Stylistic origins Electronic art music Minimalist music [1] Drone music Psychedelic rock Krautrock Space rock Frippertronics Cultural origins Early 1970s, United Kingdom Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments, electroacoustic music instruments, and any other instruments or sounds (including world instruments) with electronic processing Mainstream Low popularity Derivative forms Ambient house – Ambient techno – Chillout – Downtempo – Trance – Intelligent dance Subgenres [1] Dark ambient – Drone music – Lowercase – Black ambient – Detroit techno – Shoegaze Fusion genres Ambient dub – Illbient – Psybient – Ambient industrial – Ambient house – Space music – Post-rock Other topics Ambient music artists – List of electronic music genres – Furniture music Ambient music is a musical genre that focuses largely on the timbral characteristics of sounds, often organized or performed to evoke an "atmospheric",[2] "visual"[3] or "unobtrusive" quality. -

Five Years of the Momentum Music Fund

Five Years of the Momentum Music Fund “... a beacon of progressive investment in a transforming industry” 1 Contents FOREWORD .........................................................................................................................2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................6 INFOGRAPHIC ...................................................................................................................10 KEY FINDINGS ...................................................................................................................12 CASE STUDY – LITTLE SIMZ .............................................................................................28 CASE STUDY – SPRING KING ...........................................................................................29 CASE STUDY – YEARS AND YEARS ..................................................................................30 CASE STUDY – THIS IS THE KIT ........................................................................................31 CASE STUDY - LIFE ............................................................................................................32 CASE STUDY - MOSES BOYD ...........................................................................................33 FUTURE OF MOMENTUM ................................................................................................34 -

Analyzing Genre in Post-Millennial Popular Music

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Analyzing Genre in Post-Millennial Popular Music Thomas Johnson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2884 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ANALYZING GENRE IN POST-MILLENNIAL POPULAR MUSIC by THOMAS JOHNSON A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 THOMAS JOHNSON All rights reserved ii Analyzing Genre in Post-Millennial Popular Music by Thomas Johnson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________ ____________________________________ Date Eliot Bates Chair of Examining Committee ___________________ ____________________________________ Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Mark Spicer, advisor Chadwick Jenkins, first reader Eliot Bates Eric Drott THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract Analyzing Genre in Post-Millennial Popular Music by Thomas Johnson Advisor: Mark Spicer This dissertation approaches the broad concept of musical classification by asking a simple if ill-defined question: “what is genre in post-millennial popular music?” Alternatively covert or conspicuous, the issue of genre infects music, writings, and discussions of many stripes, and has become especially relevant with the rise of ubiquitous access to a huge range of musics since the fin du millénaire. -

The Issue Angel Haze

X AMBASSADORS • BETTY WHO • THE CHAINSMOKERS • JON BELLION • BOMBAY BICYCLE CLUB • SWITCHFOOT VARIANCETHE SIGHTS + SOUNDS YOU LOVE 40 ALBUMS TO WATCH FOR IN 2014 BASTILLE t ANGEL HAZE PHANTOGRAM JAMES VINCENT MCMORROW THE FUTURESOUNDS ISSUE VOICES THAT WILL REIGN THIS YEAR VOL. 5, ISSUE 1 | FEB_WINTER 2014 AVAILBLE NOW AT SKULLCANDY.COM @SKULLCANDY / FEATURING KAI OTTON Variancemagazine_Navigator_Kai.indd 1 12/14/12 3:10 PM TAPE MIX JAMES VINCENT MCMORROW PHANTOGRAM LILY ALLEN “Gold” “Black Out Days” “Hard Out Here” by @AlainUlises by @OJandCigs by @AleksaConic WINTER2014 VANCOUVER SLEEP CLINIC CHILDISH GAMBINO BOMBAY BICYCLE CLUB “Collapse” “telegraph ave. (‘Oakland’ by Lloyd)” “Carry Me” by @Jedshepherd by @tylersduke by @mardycum ANGEL HAZE FEAT. SIA JAMIE N COMMONS & X AMBASSADORS LO-FANG “Battle Cry” “Jungle” “#88” by @jenryannyc zz by @JK1KJ by @6n6challenge SAM SMITH MATTHEW MAYFIELD “Money on My Mind” “Heartbeat” by @AllenOVCH by @MissBehavinC YOU CREATE THE PLAYLIST ST. VINCENT "Digital Witness" Annie Clark foreshadows her new album with this catchy tune FIRSTTHINGSFIRST PHOTO BY KIM ERLANDSEN You” shot up the blogosphere last summer when video of a marriage proposal utilizing the song went viral. She’s since signed to RCA Records and is working on her major label debut. Also on the roster are X Ambassadors, the little band that could from Ithaca, N.Y. After teaming up with Alex Da Kid, who can do no wrong, in our opinion, the ris- ing act is expected to release a full-length this year. And based on everything we’ve heard so far, these guys will only continue to climb.