William Adams and Early English Enterprise in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Edicts of Toyotomi Hideyoshi: Excerpts from Limitation on the Propagation of Christianity, 1587 Excerpts from Expulsion of Missionaries, 1587

Primary Source Document with Questions (DBQs) THE EDICTS OF TOYOTOMI HIDEYOSHI: EXCERPTS FROM LIMITATION ON THE PROPAGATION OF CHRISTIANITY, 1587 EXCERPTS FROM EXPULSION OF MISSIONARIES, 1587 Introduction The unification of Japan and the creation of a lasting national polity in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries required more than just military exploits. Japan’s “three unifiers,” especially Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536- 1598) and Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616), enacted a series of social, economic, and political reforms in order to pacify a population long accustomed to war and instability and create the institutions necessary for lasting central rule. Although Hideyoshi and Ieyasu placed first priority on domestic affairs — especially on establishing authority over domain lords, warriors, and agricultural villages — they also dictated sweeping changes in Japan’s international relations. The years from 1549 to 1639 are sometimes called the “Christian century” in Japan. In the latter half of the sixteenth century, Christian missionaries, especially from Spain and Portugal, were active in Japan and claimed many converts, including among the samurai elite and domain lords. The following edicts restricting the spread of Christianity and expelling European missionaries from Japan were issued by Hideyoshi in 1587. Selected Document Excerpts with Questions From Japan: A Documentary History: The Dawn of History to the Late Tokugawa Period, edited by David J. Lu (Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1997), 196-197. © 2001 M. E. Sharpe. Reproduced with the permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. The Edicts of Toyotomi Hideyoshi: Excerpts from Limitation on the Propagation of Christianity, 1587 1. Whether one desires to become a follower of the padre is up to that person’s own conscience. -

EARLY MODERN JAPAN FALL-WINTER, 2004 Introduction: Pre-Modern Japan Through the Prism of Patronage

EARLY MODERN JAPAN FALL-WINTER, 2004 Introduction: Pre-Modern Japan that this lack of corresponding words and con- cepts is good reason to avoid using the Western Through the Prism of Patronage terms in our discussions of pre-modern East ©Lee Butler Asian art and society. And yet practices of pa- University of Michigan tronage are clearly not culture specific. Where art is found, there is patronage, even if the extent Though not unfamiliar to scholarship on pre- and types and meanings of that patronage differ modern Japan, the concept of patronage has been from place to place and culture to culture. The treated unevenly and unsystematically. The same is undoubtedly true of religion. In the term is most commonly found in studies by art paragraphs that follow I briefly summarize the historians, but even they have frequently dealt approach to early modern patronage in Western with it indirectly or tangentially. The same is scholarship and consider patronage’s value as an true of the study of the history of religion, despite interpretive concept for Japan, addressing spe- the fact that patronage was fundamental to the cifically its artistic and political forms. establishment and growth of most schools and Scholars of early modern Europe have focused sects. Works like Martin Collcutt’s Five Moun- primarily on political and cultural patronage.3 tains, with its detailed discussion of Hōjō and Political patronage was a system of personal ties imperial patronage of Zen, are rare. 1 Other and networks that advanced the interests of the scholarly approaches are more common. Per- system’s participants: patrons and clients. -

William Adams and Tokugawa Ieyasu!

Realize a NHK drama centered on William Adams and Tokugawa Ieyasu! We request for your support and cooperation with our Petition Campaign! Recognized in Japan by the name, Miura Anjin, this English sailor became the diplomatic advisor to Tokugawa Ieyasu, and greatly contributed to the development of Japan with his profound knowledge of navigation and shipbuilding. Four cities connected to Adams: Usuki of Oita prefecture, Ito of Shizuoka prefecture, Yokosuka of Kanagawa prefecture, and Hirado of Nagasaki prefecture, have formed the “ANJIN Project Committee,” and are working together to honor Adams achievements, and also propose a theme based on William Adams and Tokugawa Ieyasu for Taiga Drama. Taiga Drama is a renowned historical drama series created by NHK, Japan’s sole public broadcasting organization. Themes for this annual drama are selected from Japan’s rich history. To further increase the chances of our Taiga Drama proposal to NHK, we have started a Petition Campaign! To sign the petition, please fill your name and address on the form below: Petition Form I support the creation of a NHK Taiga Drama based around the theme of William Adams and Tokugawa Ieyasu. Address Name Prefecture* Municipality* Land number is e.g. Taro Yokosuka Kanagawa Ogawa-cho, Yokosuka not required. e.g. William Adams U.K. Medway 1 2 按針メモリアルパーク 3 4 5 三浦按針上陸記念公園 6 7 三浦按針之墓 8 9 会社名 10 *Those overseas should write your Country in “Prefecture” (e.g. U.K.) and your City in “Municipality” (e.g. Medway). ・Please submit the completed form to the division below (bring the form directly or send it by mail or FAX). -

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogunâ•Žs

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Economics Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Abstract In this study I shall discuss the marriage politics of Japan's early ruling families (mainly from the 6th to the 12th centuries) and the adaptation of these practices to new circumstances by the leaders of the following centuries. Marriage politics culminated with the founder of the Edo bakufu, the first shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616). To show how practices continued to change, I shall discuss the weddings given by the fifth shogun sunaT yoshi (1646-1709) and the eighth shogun Yoshimune (1684-1751). The marriages of Tsunayoshi's natural and adopted daughters reveal his motivations for the adoptions and for his choice of the daughters’ husbands. The marriages of Yoshimune's adopted daughters show how his atypical philosophy of rulership resulted in a break with the earlier Tokugawa marriage politics. -

A Biomolecular Anthropological Investigation of William Adams, The

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A biomolecular anthropological investigation of William Adams, the frst SAMURAI from England Fuzuki Mizuno1*, Koji Ishiya2,3, Masami Matsushita4, Takayuki Matsushita4, Katherine Hampson5, Michiko Hayashi1, Fuyuki Tokanai6, Kunihiko Kurosaki1* & Shintaroh Ueda1,5 William Adams (Miura Anjin) was an English navigator who sailed with a Dutch trading feet to the far East and landed in Japan in 1600. He became a vassal under the Shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu, was bestowed with a title, lands and swords, and became the frst SAMURAI from England. "Miura" comes from the name of the territory given to him and "Anjin" means "pilot". He lived out the rest of his life in Japan and died in Hirado, Nagasaki Prefecture, in 1620, where he was reportedly laid to rest. Shortly after his death, graveyards designated for foreigners were destroyed during a period of Christian repression, but Miura Anjin’s bones were supposedly taken, protected, and reburied. Archaeological investigations in 1931 uncovered human skeletal remains and it was proposed that they were those of Miura Anjin. However, this could not be confrmed from the evidence at the time and the remains were reburied. In 2017, excavations found skeletal remains matching the description of those reinterred in 1931. We analyzed these remains from various aspects, including genetic background, dietary habits, and burial style, utilizing modern scientifc techniques to investigate whether they do indeed belong to the frst English SAMURAI. William Adams was born in Gillingham, England in 1564. He worked in a shipyard from the age of 12, and later studied shipbuilding techniques, astronomy and navigation. -

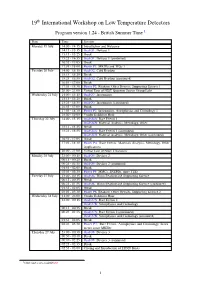

19 International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors

19th International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors Program version 1.24 - British Summer Time 1 Date Time Session Monday 19 July 14:00 - 14:15 Introduction and Welcome 14:15 - 15:15 Oral O1: Devices 1 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O1: Devices 1 (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:00 Poster P1: MKIDs and TESs 1 Tuesday 20 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O2: Cold Readout 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O2: Cold Readout (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P2: Readout, Other Devices, Supporting Science 1 20:00 - 21:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Quantum Sensor Group Labs Wednesday 21 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O3: Instruments 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O3: Instruments (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P3: Instruments, Astrophysics and Cosmology 1 18:00 - 19:00 Vendor Exhibitor Hour Thursday 22 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 (continued) Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P4: Rare Events, Materials Analysis, Metrology, Other Applications 20:00 - 21:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Cleanoom Monday 26 July 23:00 - 00:15 Oral O5: Devices 2 00:15 - 00:25 Break 00:25 - 01:55 Oral O5: Devices 2 (continued) 01:55 - 02:05 Break 02:05 - 03:30 Poster P5: MMCs, SNSPDs, more TESs Tuesday 27 July 23:00 - 00:15 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science 00:15 - 00:25 Break 00:25 - 01:55 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science -

Best of Hokkaido and Tohoku Self Guided 15 Day/14 Nights Best of Hokkaido and Tohoku Self Guided

Best of Hokkaido and Tohoku Self Guided 15 Day/14 Nights Best of Hokkaido and Tohoku Self Guided Tour Overview Experience more of Hokkaido and Tohoku on the Best of Hokkaido and Tohoku Self Guided tour. The northernmost of the main islands, Hokkaido, is Japan’s last frontier. It is a natural wonderland of mountain ranges, deep caldera lakes, active volcanoes, numerous thermally-heated mineral springs, and virgin forests. The attitudes of the inhabitants are akin to those of the pioneers of the American West, but still unmistakably Japanese. Tohoku is the northern part of Honshu, the main island of the Japanese archipelago. It is known as a remote and scenic region, and for its numerous traditional onsens, lakes, mountains, high quality rice, and welcoming people. You will enjoy exploring Tohoku’s rich cultural heritage and history, and the beautiful scenery that it has to offer. Destinations Tokyo, Sapporo, Otaru, Noboribetsu Onsen, Hakodate, Aomori, Hiraizumi, Sendai, Matsushima, Yamadera, Aizu-Wakamatsu, Ouchijuku, Kinugawa Onsen, Nikko Tour Details Among the Japanese, Hokkaido has become synonymous with sensational food, stunning scenery, and some of the best onsens in Japan. You will enjoy Sapporo, Hokkaido’s largest city and host to the 1972 Winter Olympics, with its many fine restaurants. You will have the opportunity to explore the morning market of Hakodate where you can try the local specialties of crab, sea urchin, or squid prepared for you. Here you can learn about Hokkaido’s original inhabitants, the Ainu, whose culture almost disappeared until recent efforts of restoration. Tohoku may share the main island of Honshu, but it is a world apart from the crowded and busy south. -

Iai – Naginata

Editor: Well House, 13 Keere Street, Lewes, East Sussex, England No. 301 Summer 2012 Takami Taizō - A Remarkable Teacher (Part Three) by Roald Knutsen In the last Journal I described something of Takami-sensei’s ‘holiday’ with the old Shintō- ryū Kendō Dōjō down at Charmouth in West Dorset. The first week to ten days of that early June, in perfect weather, we all trained hard in the garden of our house and on both the beach and grassy slopes a few minutes away. The main photo above shows myself, in jōdan-no-kamae against Mick Greenslade, one of our early members, on the cliffs just east of the River Char. The time was 07.30. It is always interesting to train in the open on grass, especially if the ground slopes away! Lower down, we have a pic taken when the tide was out on Lyme Bay. Hakama had to be worn high or they became splashed and sodden very quickly. It is a pity that we haven’t more photos taken of these early practices. The following year, about the same date, four of us were again at Charmouth for a few days and I recall that we had just finished keiko on the sands at 06.30 when an older man, walking his dog, came along – and we were half Copyright © 2012 Eikoku Kendo Renmei Journal of the Eikoku Kendō Renmei No. 301 Summer 2012 a mile west towards the Black Ven (for those who know Charmouth and Lyme) – He paused to look at us then politely asked if we had been there the previous year? We answered in the affirmative, to which he raised his hat, saying: ‘One Sunday morning? I remember you well. -

The Japanese Samurai Code: Classic Strategies for Success Kindle

THE JAPANESE SAMURAI CODE: CLASSIC STRATEGIES FOR SUCCESS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Boye Lafayette De Mente | 192 pages | 01 Jun 2005 | Tuttle Publishing | 9780804836524 | English | Boston, United States The Japanese Samurai Code: Classic Strategies for Success PDF Book Patrick Mehr on May 4, pm. The culture and tradition of Japan, so different from that of Europe, never ceases to enchant and intrigue people from the West. Hideyoshi was made daimyo of part of Omi Province now Shiga Prefecture after he helped take the region from the Azai Clan, and in , Nobunaga sent him to Himeji Castle to face the Mori Clan and conquer western Japan. It is an idea taken from Confucianism. Ieyasu was too late to take revenge on Akechi Mitsuhide for his betrayal of Nobunaga—Hideyoshi beat him to it. Son of a common foot soldier in Owari Province now western Aichi Prefecture , he joined the Oda Clan as a foot soldier himself in After Imagawa leader Yoshimoto was killed in a surprise attack by Nobunaga, Ieyasu decided to switch sides and joined the Oda. See our price match guarantee. He built up his capital at Edo now Tokyo in the lands he had won from the Hojo, thus beginning the Edo Period of Japanese history. It emphasised loyalty, modesty, war skills and honour. About this item. Installing Yoshiaki as the new shogun, Nobunaga hoped to use him as a puppet leader. Whether this was out of disrespect for a "beast," as Mitsuhide put it, or cover for an act of mercy remains a matter of debate. While Miyamoto Musashi may be the best-known "samurai" internationally, Oda Nobunaga claims the most respect within Japan. -

Tokugawa Ieyasu, Shogun

Tokugawa Ieyasu, Shogun 徳川家康 Tokugawa Ieyasu, Shogun Constructed and resided at Hamamatsu Castle for 17 years in order to build up his military prowess into his adulthood. Bronze statue of Tokugawa Ieyasu in his youth 1542 (Tenbun 11) Born in Okazaki, Aichi Prefecture (Until age 1) 1547 (Tenbun 16) Got kidnapped on the way taken to Sunpu as a hostage and sold to Oda Nobuhide. (At age 6) 1549 (Tenbun 18) Hirotada, his father, was assassinated. Taken to Sunpu as a hostage of Imagawa Yoshimoto. (At age 8) 1557 (Koji 3) Marries Lady Tsukiyama and changes his name to Motoyasu. (At age 16) 1559 (Eiroku 2) Returns to Okazaki to pay a visit to the family grave. Nobuyasu, his first son, is born. (At age 18) 1560 (Eiroku 3) Oda Nobunaga defeats Imagawa Yoshimoto in Okehazama. (At age 19) 1563 (Eiroku 6) Engagement of Nobuyasu, Ieyasu’s eldest son, with Tokuhime, the daughter of Nobunaga. Changes his name to Ieyasu. Suppresses rebellious groups of peasants and religious believers who opposed the feudal ruling. (At age 22) 1570 (Genki 1) Moves from Okazaki 天龍村to Hamamatsu and defeats the Asakura clan at the Battle of Anegawa. (At age 29) 152 1571 (Genki 2) Shingen invades Enshu and attacks several castles. (At age 30) 豊根村 川根本町 1572 (Genki 3) Defeated at the Battle of Mikatagahara. (At age 31) 東栄町 152 362 Takeda Shingen’s151 Path to the Totoumi Province Invasion The Raid of the Battlefield Saigagake After the fall of the Imagawa, Totoumi Province 犬居城 武田本隊 (別説) Saigagake Stone Monument 山県昌景隊天竜区 became a battlefield between Ieyasu and Takeda of Yamagata Takeda Main 堀之内の城山Force (another theoried the Kai Province. -

From Ieyasu to Yoshinao

2021 Summer Special Exhibition From Ieyasu to Yoshinao The Transition to a Powerful Pre-Modern State July 17 (Sat.) - September 12 (Sun.), 2021 INTRODUCTION Striving through the sengoku (Warring States) period, Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616) finally achieved the unification of the whole country. Yoshinao (1601-1650), the ninth son of Ieyasu, was assigned to govern the Owari domain during the era of peace. The two were father and son, yet they lived in contrasting times. Yoshinao, who inherited a large fortune of assets and texts from Ieyasu, established the foundations of the Owari domain and led Nagoya to prosperity. Focusing on the principles of their rule, passed down from Ieyasu to Yoshinao, this exhibition traces their lives, their administration, and Yoshinao’s feelings towards Ieyasu, as observed in historical documents and inherited objects. Part 1 Tokugawa Ieyasu, Toyotomi Family, and Tokugawa Yoshinao [ Exhibits Number: 1-42 ] Exhibition Rooms at Hosa Library [Section 1] Ieyasu during the Age of the Warring States: the Eve of Yoshinao’s Birth This section deals with the dramatic changes that occurred in the latter part of Ieyasu’s life, spanning the battle of Nagakute in 1584—in which Ieyasu and Nobukatsu (the second son of Nobunaga) fought Hideyoshi after Nobunaga’s death in 1582, Ieyasu’s subsequent vassalage to Hideyoshi, and the battle of Sekigahara in 1600. [Section 2] Yoshinao during the Age of the Warring States After the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi on the 18th of the 8th month of 1598, Ieyasu increasingly came into conflict with Hideyoshi’s heir, Hideyori, and his vassals of western Japan, led by Ishida Mitsunari. -

Miyagi Prefecture Is Blessed with an Abundance of Natural Beauty and Numerous Historic Sites. Its Capital, Sendai, Boasts a Popu

MIYAGI ACCESS & DATA Obihiro Shin chitose Domestic and International Air Routes Tomakomai Railway Routes Oshamanbe in the Tohoku Region Muroran Shinkansen (bullet train) Local train Shin Hakodate Sapporo (New Chitose) Ōminato Miyagi Prefecture is blessed with an abundance of natural beauty and Beijing Dalian numerous historic sites. Its capital, Sendai, boasts a population of over a million people and is Sendai仙台空港 Sendai Airport Seoul Airport Shin- filled with vitality and passion. Miyagi’s major attractions are introduced here. Komatsu Aomori Aomori Narita Izumo Hirosaki Nagoya(Chubu) Fukuoka Hiroshima Hachinohe Osaka(Itami) Shanghai Ōdate Osaka(kansai) Kuji Kobe Okinawa(Naha) Oga Taipei kansen Akita Morioka Honolulu Akita Shin Miyako Ōmagari Hanamaki Kamaishi Yokote Kitakami Guam Bangkok to the port of Hokkaido Sakata Ichinoseki (Tomakomai) Shinjō Naruko Yamagata Shinkansen Ishinomaki Matsushima International Murakami Yamagata Sendai Port of Sendai Domestic Approx. ShiroishiZaō Niigata Yonezawa 90minutes Fukushima (fastest train) from Tokyo to Sendai Aizu- Tohoku on the Tohoku wakamatsu Shinkansen Shinkansen Nagaoka Kōriyama Kashiwazaki to the port of Nagoya Sendai's Climate Naoetsu Echigo Iwaki (℃)( F) yuzawa (mm) 30 120 Joetsu Shinkansen Nikko Precipitation 200 Temperature Nagano Utsunomiya Shinkansen Maebashi 20 90 Mito Takasaki 100 10 60 Omiya Tokyo 0 30 Chiba 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Publication Date : December 2019 Publisher : Asia Promotion Division, Miyagi Prefectural Government Address : 3-8-1 Honcho, Aoba-ku, Sendai, Miyagi