FÜTİRİST TİPOGRAFİ FUTURIST TYPOGRAPHY Ayşe Derya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Legacy of Futurism's Obsession with Speed in 1960S

Deus (ex) macchina: The Legacy of Futurism’s Obsession with Speed in 1960s Italy Adriana M. Baranello University of California, Los Angeles Il Futurismo si fonda sul completo rinnovamento della sensibilità umana avvenuto per effetto delle grandi scoperte scientifiche.1 In “Distruzione di sintassi; Imaginazione senza fili; Parole in lib- ertà” Marinetti echoes his call to arms that formally began with the “Fondazione e Manifesto del Futurismo” in 1909. Marinetti’s loud, attention grabbing, and at times violent agenda were to have a lasting impact on Italy. Not only does Marinetti’s ideology reecho throughout Futurism’s thirty-year lifespan, it reechoes throughout twentieth-century Italy. It is this lasting legacy, the marks that Marinetti left on Italy’s cultural subconscious, that I will examine in this paper. The cultural moment is the early Sixties, the height of Italy’s boom economico and a time of tremendous social shifts in Italy. This paper will look at two specific examples in which Marinetti’s social and aesthetic agenda, par- ticularly the nuova religione-morale della velocità, speed and the car as vital reinvigorating life forces.2 These obsessions were reflected and refocused half a century later, in sometimes subtly and sometimes surprisingly blatant ways. I will address, principally, Dino Risi’s 1962 film Il sorpasso, and Emilio Isgrò’s 1964 Poesia Volkswagen, two works from the height of the Boom. While the dash towards modernity began with the Futurists, the articulation of many of their ideas and projects would come to frui- tion in the Boom years. Leslie Paul Thiele writes that, “[b]reaking the chains of tradition, the Futurists assumed, would progressively liberate humankind, allowing it to claim its birthright as master of its world.”3 Futurism would not last to see this ideal realized, but parts of their agenda return continually, and especially in the post-war period. -

The Train and the Cosmos: Visionary Modernity

The Train and the Cosmos: Visionary Modernity Matilde Marcolli 2015 • Mythopoesis: the capacity of the human mind to spontaneously generate symbols, myths, metaphors, ::: • Psychology (especially C.G. Jung) showed that the human mind (especially the uncon- scious) continuously generates a complex lan- guage of symbols and mythology (archetypes) • Religion: any form of belief that involves the supernatural • Mythopoesis does not require Religion: it can be symbolic, metaphoric, lyrical, visionary, without any reference to anything supernatural • Visionary Modernity has its roots in the Anarcho-Socialist mythology of Progress (late 19th early 20th century) and is the best known example of non-religious mythopoesis 1 Part 1: Futurist Trains 2 Trains as powerful symbol of Modernity: • the world suddenly becomes connected at a global scale, like never before • trains collectively drive humankind into the new modern epoch • connected to another powerful symbol: electricity • importance of the train symbolism in the anarcho-socialist philosophy of late 19th and early 20th century (Italian and Russian Futurism avant garde) 3 Rozanova, Composition with Train, 1910 4 Russolo, Dynamism of a Train, 1912 5 From a popular Italian song: Francesco Guccini \La Locomotiva" ... sembrava il treno anch'esso un mito di progesso lanciato sopra i continenti; e la locomotiva sembrava fosse un mostro strano che l'uomo dominava con il pensiero e con la mano: ruggendo si lasciava indietro distanze che sembravano infinite; sembrava avesse dentro un potere tremendo, la stessa forza della dinamite... ...the train itself looked like a myth of progress, launched over the continents; and the locomo- tive looked like a strange monster, that man could tame with thought and with the hand: roaring it would leave behind seemingly enor- mous distances; it seemed to contain an enor- mous might, the power of dynamite itself.. -

Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2

MIT 4.602, Modern Art and Mass Culture (HASS-D) Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2 PHOTOGRAPHY, PROPAGANDA, MONTAGE: Soviet Avant-Garde “We are all primitives of the 20th century” – Ivan Kliun, 1916 UNOVIS members’ aims include the “study of the system of Suprematist projection and the designing of blueprints and plans in accordance with it; ruling off the earth’s expanse into squares, giving each energy cell its place in the overall scheme; organization and accommodation on the earth’s surface of all its intrinsic elements, charting those points and lines out of which the forms of Suprematism will ascend and slip into space.” — Ilya Chashnik , 1921 I. Making “Modern Man” A. Kasimir Malevich – Suprematism 1) Suprematism begins ca. 1913, influenced by Cubo-Futurism 2) Suprematism officially launched, 1915 – manifesto and exhibition titled “0.10 The Last Futurist Exhibition” in Petrograd. B. El (Elazar) Lissitzky 1) “Proun” as utopia 2) Types, and the new modern man C. Modern Woman? 1) Sonia Terk Delaunay in Paris a) “Orphism” or “organic Cubism” 1911 b) “Simultaneous” clothing, ceramics, textiles, cars 1913-20s 2) Natalia Goncharova, “Rayonism” 3) Lyubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova stage designs II. Monuments without Beards -- Vladimir Tatlin A. Constructivism (developed in parallel with Suprematism as sculptural variant) B. Productivism (the tweaking of “l’art pour l’art” to be more socialist) C. Monument to the Third International (Tatlin’s Tower), 1921 III. Collapse of the Avant-Garde? A. 1937 Paris Exposition, 1937 Entartete Kunst, 1939 Popular Front B. -

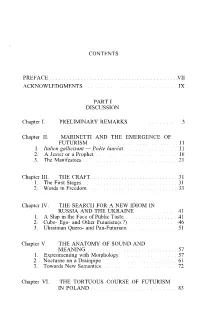

Contents Preface Vii Acknowledgments Ix Part I

CONTENTS PREFACE VII ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IX PART I DISCUSSION Chapter I. PRELIMINARY REMARKS 3 Chapter II. MARINETTI AND THE EMERGENCE OF FUTURISM 11 1. Italien gallicisant — Poète lauréat 11 2. A Jester or a Prophet 16 3. The Manifestoes 21 Chapter III. THE CRAFT 31 1. The First Stages 31 2. Words in Freedom 33 Chapter IV. THE SEARCH FOR A NEW IDIOM IN RUSSIA AND THE UKRAINE 41 1. A Slap in the Face of Public Taste 41 2. Cubo- Ego- and Other Futurism(s ?) 46 3. Ukrainian Quero- and Pan-Futurism 51 Chapter V. THE ANATOMY OF SOUND AND MEANING 57 1. Experimenting with Morphology 57 2. Nocturne on a Drainpipe 61 3. Towards New Semantics 72 Chapter VI. THE TORTUOUS COURSE OF FUTURISM IN POLAND 83 XII FUTURISM IN MODERN POETRY Chapter VII. THE FURTHER EXPANSION OF THE FUTURIST IDEAS 97 1. Futurism in Czech and Slovak Poetry 97 2. Slovenia 102 3. Spain and Portugal 107 4. Brazil 109 Chapter VIII. CONCLUSION 117 PART II A SELECTION OF FUTURIST POETRY I. ITALY 125 A. FREE VERSE 125 Libero Altomare Canto futurista 126 A Futurist Song 127 A un aviatore 130 To an Aviator 131 Enrico Cardile Ode alia violenza 134 Ode to Violence 135 Enrico Cavacchioli Fuga in aeroplano 142 Flight in an Aeroplane 143 Auro D'Alba II piccolo re 146 The Little King 147 Luciano Folgore L'Elettricità 150 Electricity 151 F.T. Marinetti À l'automobile de course 154 To a Racing Car 155 Armando Mazza A Venezia 158 To Venice 159 Aldo Palazzeschi E lasciatemi divertire 164 And Let Me Have Fun 165 B. -

Cubism Futurism Art Deco

20TH Century Art Early 20th Century styles based on SHAPE and FORM: Cubism Futurism Art Deco to show the ‘concept’ of an object rather than creating a detail of the real thing to show different views of an object at once, emphasizing time, space & the Machine age to simplify objects to their most basic, primitive terms 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Pablo Picasso 1881-1973 Considered most influential artist of 20th Century Blue Period Rose Period Analytical Cubism Synthetic Cubism 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Early works by a young Picasso Girl Wearing Large Hat, 1901. Lola, the artist’s sister, 1901. 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Blue Period (1901-1904) Moves to Paris in his late teens Coping with suicide of friend Paintings were lonely, depressing Major color was BLUE! 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Pablo Picasso, Blue Nude, 1902. BLUE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Pablo Picasso, Self Portrait, 1901. BLUE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Pablo Picasso, Tragedy, 1903. BLUE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Pablo Picasso, Le Gourmet, 1901. BLUE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s work at the National Gallery (DC) 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Rose Period Rose Period (1904-1906) Much happier art than before Circus people as subjects Reds and warmer colors Pablo Picasso, Harlequin Family, 1905. ROSE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Rose Period Pablo Picasso, La Familia de Saltimbanques, 1905. -

NATALIA-GONCHAROVA EN.Pdf

INDEX Press release Fact Sheet Photo Sheet Exhibition Walkthrough A CLOSER LOOK Goncharova and Italy: Controversy, Inspiration, Friendship by Ludovica Sebregondi ‘A spritual autobiography’: Goncharova’s exhibition of 1913 by Evgenia Iliukhina Activities in the exhibition and beyond List of the works Natalia Goncharova A woman of the avant-garde with Gauguin, Matisse and Picasso Florence, Palazzo Strozzi, 28.09.2019–12.01.2020 #NataliaGoncharova This autumn Palazzo Strozzi will present a major retrospective of the leading woman artist of the twentieth- century avant-garde, Natalia Goncharova. Natalia Goncharova will offer visitors a unique opportunity to encounter Natalia Goncharova’s multi-faceted artistic output. A pioneering and radical figure, Goncharova’s work will be presented alongside masterpieces by the celebrated artists who served her either as inspiration or as direct interlocutors, such as Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Giacomo Balla and Umberto Boccioni. Natalia Goncharova who was born in the province of Tula in 1881, died in Paris in 1962 was the first women artist of the Russian avant-garde to reach fame internationally. She exhibited in the most important European avant-garde exhibitions of the era, including the Blaue Reiter Munich, the Deutsche Erste Herbstsalon at the Galerie Der Sturm in Berlin and at the post-impressionist exhibition in London. At the forefront of the avant- garde, Goncharova scandalised audiences at home in Moscow when she paraded, in the most elegant area of the city with her face and body painted. Defying public morality, she was also the first woman to exhibit paintings depicting female nudes in Russia, for which she was accused and tried in Russian courts. -

'Kurt Schwitters in England', Baltic, No 4, Gateshea

1 KURT SCHWITTERS IN ENGLAND, Sarah Wilson, Courtauld Institute of Art, ‘Kurt Schwitters in England', Baltic, no 4, Gateshead, np, 1999 (unfootnoted version); ‘Kurt Schwitters en Inglaterra el "Anglismo" o la dialéctica del exilio’, Kurt Schwitters, IVAM Centre Julio González, Valencia, pp. 318-335, 1995 ‘Kurt Schwitters en Angleterre’, Kurt Schwitters, retrospective, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, pp. 296-309 `ANGLISM': THE DIALECTICS OF EXILE' Three orthodoxies have dictated previous accounts of the life of Kurt Schwitters in England: that England was simply `exile', a cultural desert, that he was lonely, unappreciated, that his late figurative work is too embarrassing to be displayed in any authoritative retrospective. Scholars ask `What if?' What if Schwitters had got a passport to United States and had joined other artists in exile? He would have continued making Merz with American material. He would have had no `need' to paint figuratively.1 Would he have fitted his past into an even more `modernist' mould like his friend Naum Gabo, to please the New Yorkers?2 Surely not. `Emigration is the best school of dialectics' declared Bertold Brecht.3 Schwitters' last period must be investigated not in terms of `exile' but the dialectics of exile: as a future which cuts off a past which lives on through it all the more intensely in memory, repetition, recreation. `Exile' moreover is a purely negative term, foreclosing all the inspirational possibilities of a new `genius loci', a spirit of place: England. The Germany Schwitters knew was disfigured, disintegrating, self-destructing. His longing was for place which was no more. His Merzbau was destroyed by Allied bombing in 1943; Helma died in 1944: `Hanover a heap of ruins, Berlin destroyed, and you're not allowed to say how you feel.'4 The English period was a both a death and a birth, a question of identity through time, of new and old languages. -

Downloaded 2021-09-26T23:35:06Z

Provided by the author(s) and University College Dublin Library in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title "The Futurist Mountains": F.T. Marinetti's experiences of mountain combat in the First World War Authors(s) Daly, Selena Publication date 2013-06-24 Publication information Modern Italy, 18 (4): 323-338 Publisher Routledge (Taylor & Francis) Item record/more information http://hdl.handle.net/10197/4507 Publisher's statement This is an electronic version of an article published in Modern Italy. Modern Italy is available online at: www.tandfonline.com//doi/abs/10.1080/13532944.2013.806289 Publisher's version (DOI) 10.1080/13532944.2013.806289 Downloaded 2021-09-26T23:35:06Z The UCD community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters! (@ucd_oa) © Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. ‘TheFuturistmountains’:FilippoTommasoMarinetti’sexperiencesof mountaincombatintheFirstWorldWar SelenaDaly 1VCMJTIFEJO.PEFSO*UBMZ +VOF Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s first experience of active combat was as a member of the Lombard Battalion of Volunteer Cyclists and Motorists in the autumn of 1915, when he fought in the mountains of Trentino at the border of Italy and Austria Hungary. This article examines his experience of mountain combat and how he communicated aspects of it both to specialist, Futurist audiences and to the general public and soldiers, through newspaper articles, manifestos, ‘words in freedom’ drawings, speeches and essays written between 1915 and 1917. Marinetti’s aim in all of these wartime writings was to gain maximum support for the Futurist movement. -

Transition in Post-Soviet Art

Transition in Post-Soviet Art: “Collective Actions” Before and After 1989 by Octavian Eșanu Department of Art, Art History & Visual Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Supervisor ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Patricia Leighten ___________________________ Pamela Kachurin ___________________________ Valerie Hillings Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History & Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 ABSTRACT Transition in Post-Soviet Art: “Collective Actions” Before and After 1989 by Octavian Eșanu Department of Art, Art History & Visual Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Supervisor ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Patricia Leighten ___________________________ Pamela Kachurin ___________________________ Valerie Hillings An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History & Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 Copyright by Octavian Eșanu 2009 ABSTRACT For more than three decades the Moscow-based conceptual artist group “Collective Actions” has been organizing actions. Each action, typically taking place at the outskirts of Moscow, is regarded as a trigger for a series of intellectual -

Alexandra Exter's Dynamic City in 1913

GEORGII KOVALENKO Alexandra Exter’s Dynamic City in 1913 Georgii Kovalenko is a Doctor of Art History, head of the Department of 20th century Russian Art at the Research Institute of the Theory and History of Fine Arts at the Russian Academy of Art, and the lead scientist at the State Institute of Art History. He is the deputy chairman of the Commission for the Study of Avant-Garde Art of the 1910s and 1920s at the Russian Academy of Sciences, as well as the editor of the series h!VANT 'ARDE!RTOFTHESANDSvINVOLUMES ANDh2USSIAN !RTTH#ENTURYvINVOLUMES (ISPUBLICATIONSINCLUDEAlexandra Exter – Farbrhytthmen (State Russian Museum, 2001) and iÝ>`À>Ê ÝÌiÀÊUÊÊ Retrospective (Moscow Museum of Modern Art, 2010). 34 Alexandra Exter painted one night landscape after into it, demanding to be remembered, as if in another minute another. Night time streets, buildings with darkened it will change unrecognizably, disappear, go out and be carried windows, deep shadows on gleaming sidewalks and sharp rays away along with the frantically flying lights. diverging in a cone shape – light from streetlamps and from car headlights, tram lights. Exter sometimes indicated the relevant city in the titles of her works – Kiev (Fundakleyevskaya Street), Florence – but more often it is just City at Night, just Night Time City. And geographical details add little, in essence, to the painting: speaking generally we are looking at one and the same city. And the important thing is that it is a city at night. And it so resembles the Paris described by Apollinaire: Night of Paris, drunk on gin, Filled with electric light. -

BOOK ARTS NEWSLETTER ISSN 1754-9086 No

BOOK ARTS NEWSLETTER ISSN 1754-9086 No. 128 November 2019 Published by Impact Press at the Centre for Fine Print Research, UWE Bristol, UK ARTIST’S COVER PAGE: TIM HOPKINS / HALF PINT PRESS - IMAGINARY LETTERS In this issue: National and International Artists’ Books Exhibitions Pages 2 - 17 Courses, Conferences, Lectures & Workshops Pages 18 - 25 Opportunities Pages 25 - 34 Artist’s Book Fairs & Events Pages 35- 37 Internet News Pages 37 - 38 New Artists’ Publications Pages 38 - 52 Reports & Reviews Pages 52 - 56 Stop Press! Pages 56 - 63 Artists’ Books Exhibitions in the Bower Ashton Library It writes Soares’s ideas across the everyday detritus of showcases, UWE, Bristol, UK a life lived, on objects as diverse as a postage stamp, a compliments slip, a booze label, a page of accounts and an Tim Hopkins / Half Pint Press internal transit envelope. Not all the objects are paper: the The Book of Disquiet and Imaginary Letters box includes a pencil, a lollipop stick and a matchbook. 1st - 30th November 2019 Some are beautiful, others grubbily everyday. Likewise the box, which is deliberately not a cloth-bound fine press Tim Hopkins will be showing two bookworks: The Book of production but instead hand-printed on a commercially- Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa (2017), and Imaginary Letters available stitched board box. by Mary Butts (2019). The impression is of a box of belongings, each with a value The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa. of some kind to the owner. Each may be kept because it’s The texts that make up The Book of Disquiet were found in a beautiful, or important, or useful, or attached to a memory: box in Pessoa’s room after his death in 1935. -

Kirill Zdanevich Way of Orchestra Life

Kirill Zdanevich Way of Orchestra Life Салами арцивебс Салами футуризм Vasily Kamensky1 The Polish-Georgian family of Mikhail Zdanevich, the heir of a Polish officer having rebelled against the Russian Empire and Valentina Gamkrelidze, the daughter of an impoverished nobleman Rostom Gamkrelidze lived in Aguri (Brick) Street, Tiflis. Valentina Gamkrelidze trained her sons, Kirill and Ilia, to keep diaries from their childhood. It developed into a life-long habit, and today it is those diaries that we learn Kirill’s life history from. In the summer of 1907, 15-year old Kirill, together with his cousin Valodia Mrozovsky, wrote ingenuous, boyish stories about a tin soldier having got from a toy factory in a Tiflis store where he met with a thrilling adventure (this was a story that completely differed from the tale of H.C. Andersen) and illustrated the story with his own drawings. The notebook with a blue cover and the rarest notebook-like books will re-appear in Kirill Zdanevich’s life some ten years later and become one of the determinants of his work and, generally, of the uniqueness of Tiflis Avant-garde. The desire to learn drawing prevailed over his ardor for literature. From the age of 8 Kirill attended N. Sklifosofsky’s School of Painting and Drawing. He used to repeatedly process figures and details reverting again and again to one and the same motif. His ardor with Impressionism was the result of the influence of the artists – Fogel and Sklifosofsky; the painting tendencies used to reach Georgia as well as the entire Empire from the West when they were already coming to their end there.