A New Approach to Biography in Early Medieval China: the Case of Zuo Si

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animals and Morality Tales in Hayashi Razan's Kaidan Zensho

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses March 2015 The Unnatural World: Animals and Morality Tales in Hayashi Razan's Kaidan Zensho Eric Fischbach University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fischbach, Eric, "The Unnatural World: Animals and Morality Tales in Hayashi Razan's Kaidan Zensho" (2015). Masters Theses. 146. https://doi.org/10.7275/6499369 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/146 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNNATURAL WORLD: ANIMALS AND MORALITY TALES IN HAYASHI RAZAN’S KAIDAN ZENSHO A Thesis Presented by ERIC D. FISCHBACH Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 2015 Asian Languages and Literatures - Japanese © Copyright by Eric D. Fischbach 2015 All Rights Reserved THE UNNATURAL WORLD: ANIMALS AND MORALITY TALES IN HAYASHI RAZAN’S KAIDAN ZENSHO A Thesis Presented by ERIC D. FISCHBACH Approved as to style and content by: __________________________________________ Amanda C. Seaman, Chair __________________________________________ Stephen Miller, Member ________________________________________ Stephen Miller, Program Head Asian Languages and Literatures ________________________________________ William Moebius, Department Head Languages, Literatures, and Cultures ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank all my professors that helped me grow during my tenure as a graduate student here at UMass. -

Treating Osteoarthritis with Chinese Herbs by Jake Schmalzriedt, DOM

TREATING OSTEOARTHRITIS WITH CHINESE HERBS By Jake Schmalzriedt, DOM Osteoarthritis is a progressive joint disorder that is also known as WESTERN MEDICAL DIAGNOSIS degenerative joint disease, degenerative arthritis, osteoarthrosis Western diagnosis is made primarily from signs and symptoms, (implying lack of inflammation), and commonly “wear and tear” history, and a physical exam checking for tenderness, alignment, arthritis. It is the gradual breakdown of cartilage in the joints and gait, stability, range of motion, and absence of an inflammatory the development of bony spurs at the margins of the joints. The response (heat, redness, and swelling). Western blood work is term osteoarthritis is derived from the Greek words, osteo mean- also used to rule out rheumatoid arthritis and gout. X-rays can ing bone, arthro meaning joint, and itis referring to inflamma- show joint narrowing and osteophyte formation, confirming the tion. This is somewhat of a contradictory term as osteoarthritis osteoarthritis diagnosis. generally has little inflammation associated with it. WESTERN MEDICAL TREATMENT Osteoarthritis falls under rheumatic diseases. There are two main The Western medical treatment principle is categories of arthritis: inflammatory and non- Cartilage and symptomatic relief and supportive therapy inflammatory. Osteoarthritis belongs in the Bone Fragment Normal Bone with an emphasis on controlling pain, in- non-inflammatory category. There are over Thinned Cartilage creasing function and range of motion, and 100 different types of arthritis (all sharing the Normal Cartilage improving quality of life. common symptom of persistent joint pain) Eroded Cartilage with osteoarthritis being the most common Western Therapy and affecting over 27 million people in the Physical therapy and gentle exercises are United States. -

Is Shuma the Chinese Analog of Soma/Haoma? a Study of Early Contacts Between Indo-Iranians and Chinese

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 216 October, 2011 Is Shuma the Chinese Analog of Soma/Haoma? A Study of Early Contacts between Indo-Iranians and Chinese by ZHANG He Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation A/L Krishnan Thiinash Bachelor of Information Technology March 2015 A/L Selvaraju Theeban Raju Bachelor of Commerce January 2015 A/P Balan Durgarani Bachelor of Commerce with Distinction March 2015 A/P Rajaram Koushalya Priya Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Hiba Mohsin Mohammed Master of Health Leadership and Aal-Yaseen Hussein Management July 2015 Aamer Muhammad Master of Quality Management September 2015 Abbas Hanaa Safy Seyam Master of Business Administration with Distinction March 2015 Abbasi Muhammad Hamza Master of International Business March 2015 Abdallah AlMustafa Hussein Saad Elsayed Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Abdallah Asma Samir Lutfi Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdallah Moh'd Jawdat Abdel Rahman Master of International Business July 2015 AbdelAaty Mosa Amany Abdelkader Saad Master of Media and Communications with Distinction March 2015 Abdel-Karim Mervat Graduate Diploma in TESOL July 2015 Abdelmalik Mark Maher Abdelmesseh Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Master of Strategic Human Resource Abdelrahman Abdo Mohammed Talat Abdelziz Management September 2015 Graduate Certificate in Health and Abdel-Sayed Mario Physical Education July 2015 Sherif Ahmed Fathy AbdRabou Abdelmohsen Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdul Hakeem Siti Fatimah Binte Bachelor of Science January 2015 Abdul Haq Shaddad Yousef Ibrahim Master of Strategic Marketing March 2015 Abdul Rahman Al Jabier Bachelor of Engineering Honours Class II, Division 1 -

Ch'uan Shu Tsung Mu, Ch

F '£2i)l,(: j{, :;i/(r;l£'fili w,,, \l0 t 11<,,,,.,;,s-1y:.tls\ '"'%•,:5 ,\f�i)�frIS ·!M . '.� ' , \,jf:); 'ii• • " &i >�,, i - ., .., ;;. · .... - .. ERR AT.A Page 5: Line 11, fill in characters for Che-tung it� Az . ,Linen·12, after the·word "written",. .fill inih}Jl . .Line 15,· . after the ·word "wr.i te� ", , fill· in .,fN . .Line 31 should. read,. "Comment: we·hold·.that rl y·ang· ip, written .f MAN SHU Book of the southern Barbarians THE CORNELL UNIVERSITY SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM The Southeast Asia Program was organized at Cornell University in the Department of Far Eastern Studies in 1950. It is a teaching and research program of inter- · disciplinary studies in the humanities, social sciences, and some natural sciences. It deals with Southeast Asia as a region, and with the individual countries of the area: Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaya, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. The activities of the Program are carried on both at Cornell and in southeast Asia. They include an under graduate and graduate curriculum at Cornell which provides instruction by special.ists in southeast Asian cultural history and present-day aff�irs and offers intensive train� ing in each of the major languages of the area. The Program sponsors group research projects on Thailand, on Indonesia, on the Philippines, and on the area's Chinese minorities. At the same time, individual staff and students of the Program have done field research in every Southeast Asian country• . A list of publications relating to Southeast Asia which may be obtained on prepaid order directly from the Program is given at the end of this volume. -

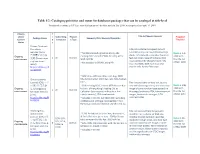

Chinese Language Resources Cataloging Priorities and Status

Table 1/2: Cataloging priorities and status for databases/packages that can be cataloged at title-level Prioritized according to UC East Asian bibliographers’ decision made in July 2009; status updated on April 19, 2010 Priority T and/or i Subscribing Resourc Title list/Vendor Records Proposed Package Name Summary/OCLC Records/OpenURLs Current e Campuses e Type Timeline/ Status r Taiwan Electronic Periodicals Title list available by request but not Services (TEPS) = *700 titles (including hidden titles), 280 available online, no new titles/coverage Done in July 台灣電子期刊服 alerts; rich metadata, one clear (zoom-in Ongoing existing OCLC records (~40% hit rate), 420 k- 2008 with 務網 2 all Journals feature) cover image of some random maintenance (Taiwan dian level records the title list zi qi kan fu wu issue posted, title changes listed; 10% *Not included in SFX KB, using PID of Apr. 2008 wang) incorrect ISSNs; 40% have incorrect http://uclibs.org/P imprint info. for the first issue ID/126969 *3400 titles, 400 new titles from Aug. 2008 China Academic title list (initial list: 2007 Dec. list), 600+ hidden Journals (CAJ) = 中 titles Title lists available on Web site, but no 国期刊全文数据 *3200 existing OCLC records (97% hit rate due new titles/coverage alerts; one blur cover Done in May Ongoing 库 (Zhongguo qi to Univ. of Hong Kong’s loading CAJ as image of some random issue posted, no 2009 with 1 all Journals maintenance kan quan wen shu Collection Sets recently, with quite a few title page/back cover/TOC/advertisement the title list ju ku) hybrid records,), 75 k-level records images, hidden title changes; 9.7% of Dec. -

Origins of Nature Tourism in Imperial China

Origins of nature tourism in imperial China Libo Yan Abstract Libo Yan is based at the Faculty Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to apply what can be learned from the emergence of nature tourism of Hospitality and Tourism to understand some current and future trends of tourism. Management, Macau Design/methodology/approach – This study adopted the evolutionary paradigm for investigation. University of Science and Findings – The emergence of nature tourism in early medieval China can be attributed to four major factors, Technology, Macau, China. including transformation of value orientations, seeking longevity, interest in suburbs and population migration. Research limitations/implications – Historical studies help understand the current and future trends. When the contributing factors for nature tourism are linked to the contemporary world, it can be found that these factors are still playing a part in shaping tourism trends or patterns in their original or alternative forms. These trends or patterns are worthy of scholarly investigations. Originality/value – This paper offers a comprehensive understanding of the origins of nature tourism. Keywords Early medieval China, Landscape appreciation, Population migration, Seeking longevity, Suburban excursions, Value transformation Paper type Research paper Introduction The origins of tourism have been a fascinating area for investigation. According to Cohen (1972, as cited in Stronza, 2001), such investigation should pay attention to the specific forms of tourism as different forms of tourism might have different origins. It is thus necessary to examine the social, political and environmental factors that caused the emergence of certain types of tourism (Dann, 1981, as cited in Stronza, 2001). In the broad sense, tourism can be classified into two types, cultural tourism and nature tourism. -

Linguistic Composition and Characteristics of Chinese Given Names DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.51/2016/8

Onoma 51 Journal of the International Council of Onomastic Sciences ISSN: 0078-463X; e-ISSN: 1783-1644 Journal homepage: https://onomajournal.org/ Linguistic composition and characteristics of Chinese given names DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.51/2016/8 Irena Kałużyńska Sinology Department Faculty of Oriental Studies University of Warsaw e-mail: [email protected] To cite this article: Kałużyńska, Irena. 2016. Linguistic composition and characteristics of Chinese given names. Onoma 51, 161–186. DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.51/2016/8 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.34158/ONOMA.51/2016/8 © Onoma and the author. Linguistic composition and characteristics of Chinese given names Abstract: The aim of this paper is to discuss various linguistic and cultural aspect of personal naming in China. In Chinese civilization, personal names, especially given names, were considered crucial for a person’s fate and achievements. The more important the position of a person, the more various categories of names the person received. Chinese naming practices do not restrict the inventory of possible given names, i.e. given names are formed individually, mainly as a result of a process of onymisation, and given names are predominantly semantically transparent. Therefore, given names seem to be well suited for a study of stereotyped cultural expectations present in Chinese society. The paper deals with numerous subdivisions within the superordinate category of personal name, as the subclasses of surname and given name. It presents various subcategories of names that have been used throughout Chinese history, their linguistic characteristics, their period of origin, and their cultural or social functions. -

The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933

The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Schluessel, Eric T. 2016. The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493602 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 A dissertation presented by Eric Tanner Schluessel to The Committee on History and East Asian Languages in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History and East Asian Languages Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April, 2016 © 2016 – Eric Schluessel All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Mark C. Elliott Eric Tanner Schluessel The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933 Abstract This dissertation concerns the ways in which a Chinese civilizing project intervened powerfully in cultural and social change in the Muslim-majority region of Xinjiang from the 1870s through the 1930s. I demonstrate that the efforts of officials following an ideology of domination and transformation rooted in the Chinese Classics changed the ways that people associated with each other and defined themselves and how Muslims understood their place in history and in global space. -

Revista De Cultura Revista De Cultura Review of Culture INSTITUTO CULTURAL Do Governo Da R.A.E De Macau

55 International Edition 55 Edição Internacional 2017 International Edition Edição Internacional Revista de Cultura Revista Revista de Cultura Review of Culture INSTITUTO CULTURAL do Governo da R.A.E de Macau do Governo CULTURAL INSTITUTO Review of Culture Review IC Assine a EDITOR é uma revista de Cultura e, domínio do Espírito, é Livre. Avassalada Publisher ao encontro universal das culturas, servente da identidade cultural de Revista de Cultura Subscribe to INSTITUTO CULTURAL Macau, agente de mais íntima relação entre o Oriente e o Ocidente, do Governo da Região Administrativa particularmente entre a China e Portugal. RC propõe-se publicar todos Review of Culture Especial de Macau os textos interessantes aos objectivos confessados, pelo puro critério da CONSELHO DE DIRECÇÃO qualidade. Assim, as opiniões e as doutrinas, expressas ou professas nos textos Editorial Board assinados, ou implícitas nas imagens de autoria, são da responsabilidade Leung Hio Ming, Chan Peng Fai, dos seus autores, e nem na parte, nem no todo, podem confundir-se com a Wong Man Fai, Luís Ferreira orientação da RC. A Direcção da revista reserva-se o direito de não publicar, [email protected] nem devolver, textos não solicitados. EDITOR EXECUTIVO é uma revista simultaneamente publicada nas versões Chinesa e Executive Editor Internacional (em Português e Inglês). Buscando o diálogo e o encontro Sofia Salgado francos de Culturas, RC tem na limpidez a vocação e na transparência [email protected] o seu processo. COORDENADOR Co-ordinator Luís Ferreira is a cultural magazine published in two versions — Chinese and [email protected] International (Portuguese/English)—whose purpose is to reflect the uni- que identity of Macao. -

Study on the Rise and Fall of the Duyi Fu and Geography Record of the Pre-Tang Dynasty and the Mutual Influence

2017 International Conference on Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities (SSAH 2017) Study on the Rise and Fall of the Duyi Fu and Geography Record of the Pre-Tang Dynasty and The Mutual Influence Tongen Li College of Chinese Language and Literature of Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, Gansu, 730070 Keywords: The Duyi Fu, The Geography Record, The Earthly Consciousness, The Literariness, The Mutual Influence Abstract. There are two important regional works in the Tang Dynasty. As an important subject of Fu literature, it has a close relationship with the flourishing period of the Wei, Jin and Southern and Northern Dynasties. Both have a common origin, but also has a different development track; both self-contained, but also mutual influence. The artistic nature of the city and the nature of the material are permeated with each other, and the development and new changes are promoted. Introduction Duyi Fu, including Jingdu Fu and Yi Ju Fu, began in the Western Han Dynasty, to Yang Xiong "Shu Du Fu" as the earliest. Xiao Tong "anthology" received more than 90 articles, divided into 15 categories, the first category of "Kyoto", income 8; Li Fang and others compiled "Wen Yuan Yinghua" sub-43, "Kyoto" Yi "in the head; Chen Yuan-long series of" calendar Fu "column" city "head, a total of 10 volumes of 70 articles. Duyi Fu mainly revolves around the geography, politics, culture and social life of the metropolis,used for singing praises of the emperor and boast of their homelands, with obvious geographical characteristics. Geography Record also known as the geography, geography or geography book, "Sui Shu · books catalogue" called it "geography". -

Names of Chinese People in Singapore

101 Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 7.1 (2011): 101-133 DOI: 10.2478/v10016-011-0005-6 Lee Cher Leng Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore ETHNOGRAPHY OF SINGAPORE CHINESE NAMES: RACE, RELIGION, AND REPRESENTATION Abstract Singapore Chinese is part of the Chinese Diaspora.This research shows how Singapore Chinese names reflect the Chinese naming tradition of surnames and generation names, as well as Straits Chinese influence. The names also reflect the beliefs and religion of Singapore Chinese. More significantly, a change of identity and representation is reflected in the names of earlier settlers and Singapore Chinese today. This paper aims to show the general naming traditions of Chinese in Singapore as well as a change in ideology and trends due to globalization. Keywords Singapore, Chinese, names, identity, beliefs, globalization. 1. Introduction When parents choose a name for a child, the name necessarily reflects their thoughts and aspirations with regards to the child. These thoughts and aspirations are shaped by the historical, social, cultural or spiritual setting of the time and place they are living in whether or not they are aware of them. Thus, the study of names is an important window through which one could view how these parents prefer their children to be perceived by society at large, according to the identities, roles, values, hierarchies or expectations constructed within a social space. Goodenough explains this culturally driven context of names and naming practices: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore The Shaw Foundation Building, Block AS7, Level 5 5 Arts Link, Singapore 117570 e-mail: [email protected] 102 Lee Cher Leng Ethnography of Singapore Chinese Names: Race, Religion, and Representation Different naming and address customs necessarily select different things about the self for communication and consequent emphasis.