Changing Postal ZIP Code Boundaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Publication 431 (Post Office Box Fees), Provided in Response to Interrogatory DBP/USPS-155

LIBRARY REFERENCE J-216 Publication 431 (Post Office Box Fees), Provided in Response to Interrogatory DBP/USPS-155 Post Offic d Fees UNITEDSTATES POSTAL SERVUE Putllrcalion 43 I Jdriuary, 2001 Post Office ................. ............. How to Use This Publication This publication is provided to postmasters and facility managers to them in understanding the new post office box fee restructuring (see Domestic Mail Manual D910 and D920 for complete rules and standards governing post office box service and caller service). Included is a list of new fee groups for all current five-digit ZIP Codes, explanation of the new fees, WinBATS instructions, frequently asked questions, and sample letters to help you communicate the changes to your post office box customers. Please read this publication and share the information with appropriate staff members to ensure your post office box customers understand the changes and your office charges the correct fees. Table of Contents Overview.. .................................................................... 2 Effective Date of the New Fees ... .................................... 3 Key 3 ............................................................... Additional Key 3 Fee ........................................................... Lock Replacement 3 Fee.. ................................................... No-Fee (Group E) Post Office Box Service................... 4 WinBATS 4-5 Instruction....................................................... Questions and Answers 6-7 .................. .................... -

QSG 120 Priority Mail Letters, Flats, and Parcelsl

Retail Letters, Flats, and Parcels Priority Mail 120 Quick Service Guide Physical Maximum weight: 70 pounds. Standards Maximum length and girth: 108 inches. (101.5) Rates and Fees Priority Mail offers 2-day service to most domestic destinations and is often used to expedite (123.1) matter mailable as First-Class Mail, Periodicals, or Standard Mail. Priority Mail envelopes and boxes are available at no additional cost at post offices. Weight Zones Not Over (pounds) Local, 1, 2, & 3 4567 8 1 $4.05 $4.05 $4.05 $4.05 $4.05 $4.05 2 4.20 4.80 5.15 5.30 5.70 6.05 3 5.00 6.40 7.20 7.55 8.25 9.00 4 5.60 7.45 8.50 8.95 9.95 10.90 5 6.15 8.45 9.80 10.40 11.60 12.80 For rates over 5 pounds, see 123.1.3. Flat-rate envelope: $4.05, regardless of weight or destination, for material sent in a USPS Priority Mail flat-rate envelope (available at post offices) (123.1.6). Flat-rate boxes: $8.10, regardless of weight or destination, for material sent in USPS Priority Mail flat-rate boxes (available at post offices) (709.6). Balloon rate: items weighing less than 15 pounds but measuring more than 84 inches in combined length and girth are charged a minimum rate equal to that for a 15-pound parcel for the zone to which it is addressed (123.1.7). Pickup service (123.1.8): $13.25 per stop (regardless of the number of pieces); service and information available by calling 1-800-222-1811 or at www.usps.com. -

State Abbreviations

State Abbreviations Postal Abbreviations for States/Territories On July 1, 1963, the Post Office Department introduced the five-digit ZIP Code. At the time, 10/1963– 1831 1874 1943 6/1963 present most addressing equipment could accommodate only 23 characters (including spaces) in the Alabama Al. Ala. Ala. ALA AL Alaska -- Alaska Alaska ALSK AK bottom line of the address. To make room for Arizona -- Ariz. Ariz. ARIZ AZ the ZIP Code, state names needed to be Arkansas Ar. T. Ark. Ark. ARK AR abbreviated. The Department provided an initial California -- Cal. Calif. CALIF CA list of abbreviations in June 1963, but many had Colorado -- Colo. Colo. COL CO three or four letters, which was still too long. In Connecticut Ct. Conn. Conn. CONN CT Delaware De. Del. Del. DEL DE October 1963, the Department settled on the District of D. C. D. C. D. C. DC DC current two-letter abbreviations. Since that time, Columbia only one change has been made: in 1969, at the Florida Fl. T. Fla. Fla. FLA FL request of the Canadian postal administration, Georgia Ga. Ga. Ga. GA GA Hawaii -- -- Hawaii HAW HI the abbreviation for Nebraska, originally NB, Idaho -- Idaho Idaho IDA ID was changed to NE, to avoid confusion with Illinois Il. Ill. Ill. ILL IL New Brunswick in Canada. Indiana Ia. Ind. Ind. IND IN Iowa -- Iowa Iowa IOWA IA Kansas -- Kans. Kans. KANS KS A list of state abbreviations since 1831 is Kentucky Ky. Ky. Ky. KY KY provided at right. A more complete list of current Louisiana La. La. -

Certificate of Mailing — Firm

Certificate of Mailing — Firm Name and Address of Sender TOTAL NO. TOTAL NO. Affix Stamp Here of Pieces Listed by Sender of Pieces Received at Post Office™ Postmark with Date of Receipt. Postmaster, per (name of receiving employee) USPS® Tracking Number Address Postage Fee Special Handling Parcel Airlift Firm-specific Identifier (Name, Street, City, State, and ZIP Code™) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. PS Form 3665, January 2017 (Page ___ of ___ ) PSN 7530-17-000-5549 See Reverse for Instructions Instructions for Certificate of Mailing — Firm This service provides evidence that the mailer has presented individual items to 11. Present PS Form 3665 and the mailing as follows: the Postal Service™ for mailing, and is available for the following products: ¡ When the mailing has fewer than 50 mailpieces and less than 50 pounds, ™ ¡ Domestic services: First-Class Mail®, First-Class Package Service®, Priority present the form and mailing at a retail Post Office location. Mail®, Media Mail®, Library Mail, Bound Printed Matter, Merchandise Return ¡ When the mailing has at least 50 mailpieces or at least 50 pounds, ™ Service, Parcel Return Service, and USPS Retail Ground . present the form and mailing at a business mail entry unit (BMEU) or ¡ International services: First-Class Mail International® (unregistered items), USPS-authorized detached mail unit (DMU). First-Class Package International Service® (unregistered items), Free Privately Printed Forms: The Postal Service allows mailers to use Matter for the Blind, and Airmail M-bags®. USPS-approved privately printed or computer-generated firm sheets that are nearly identical in design elements and color to the USPS-provided The following instructions are for the preparation and use of PS Form 3665, PS Form 3665. -

Is Diversification the Answer to Mail Woes? the Experience of International Posts

Is Diversification the Answer to Mail Woes? The Experience of International Posts Final Report February 2010 Notice of Confidentiality and Non-Disclosure This document contains pre-decisional opinions, advice, and recommendations that are offered as part of the deliberations necessary to the formulation of postal policy. It is protected from disclosure pursuant to the Deliberative Process Privilege It also contains commercially sensitive and confidential business/proprietary information that is likewise protected from disclosure by other applicable privileges. No part of it may be circulated, quoted, or reproduced for distribution outside the client organization without prior written approval from Accenture Diversification of International Posts 1 About this document This document was prepared by Accenture at the request of the U.S. Postal Service This report is based on a review of the experience of international posts with diversification outside of mail 1, complemented by Accenture’s postal industry experience and research. It was prepared with the intent to help inform discussions on the U.S. Postal Service future growth opportunities While looking at how other posts are responding to the growing decline in mail volumes provides valuable insights, this report does not intend to provide recommendations on the U.S. Postal Service specific situation In particular, the reasons for success or failures as experienced by others posts can be rooted in a wide range of factors, among which are: market conditions, the specific situation of a given post, or the effectiveness in executing their respective diversification strategies Therefore, while this report provides a collective overview of what other posts have done to grow their revenue outside of mail, it does not intend to provide an analysis of the U.S. -

Post Office 1975-22

CHAPTER 27A POST OFFICE 1975-22 This Act came into operation on 1st January, 1981 by Proclamation (S.I. 1980 No. 196). Amended by: 1975-59 1992-17 2000-27 1992-16 1992-29 Law Revision Orders The following Law Revision Order or Orders authorized the insertion and removal of pages as the case may be under the Law Revision Act Cap.2 now repealed: 1978 1995 1985 2002 Guide to symbols in historical notes: - indicates an amendment made by an Act / indicates an amendment made by statutory instrument LAWS OF BARBADOS CUMULATIVE EDITION 2008 Printed by the Government Printer, Bay Street, St. Michael, by authority of the Government of Barbados Supplement to Official Gazette No. dated , CHAPTER 27A POST OFFICE 1975-22 Arrangement of Sections PART I PRELIMINARY 1. Short title 2. Interpretation PART II FUNCTIONS AND PRIVILEGES OF POSTMASTER-GENERAL 3. Special powers of Postmaster-General 4. Exclusive privilege of Postmaster-General PART III POSTAGE 5. Payment of postage 6. Exemption from postage 7. Unpaid or insufficiently prepaid postal articles 8. Recovery of postage THE LAWS OF BARBADOS Printed by the Government Printer, Bay Street, St. Michael by the authority of the Government of Barbados 4 POST OFFICE 9. Provision of stamps, stamped envelopes etc. PART IV REVENUE 10. Disposal of revenue PART V TRANSMISSION OF MONEY BY POST 11. Transmission of money by post PART VI UNIVERSAL POSTAL UNION 12. Arrangements for maintaining membership in Universal Postal Union PART VII CONDITIONS OF TRANSIT 13. Liability for loss, etc. of postal articles 14. Redelivery to sender of postal article 15. -

United States Postal Service As the U.S

United States Postal Service As the U.S. Postal Service continues its evolution as a forward-thinking, fast-acting company capable of providing quality products and services for its customers, it continues to remember and celebrate its roots as the first national network of communications that literally bound a nation together. Ours is a proud heritage built on a simple yet profound mission: Connect every American, every door, every business, everywhere through the simple act of delivering mail. This idea of universal service is at the heart of a $900 billion industry that drives commerce, plays an integral part of every American community and remains the greatest value of any post in the world. This is the promise and the potential of the Postal Service and it can be found on every page of “Postal Facts 2012.” Size and Scope ....................................................................................................4 A Decade of Facts and Figures ........................................................................6 People, Community, Social Responsibility ................................................7 usps.com — This Post Office is Always Open ...................................................8 Quick, Easy, Convenient .................................................................................9 A Simpler Way to Ship ........................................................................................10 What the Postal Service wants you to know .............................................12 Sustainability ....................................................................................................14 -

Customer Agreement for Premium PO Box Service Additional Services

Customer Agreement for Premium PO Box Service Additional Services The Postal Service is offering the following services for PO Box customers at this Post Office® location: • Street Addressing Service • Signature on File A. Street Addressing Service for your PO Box With Street Addressing Service, you have the option of using the street address of this Post Office location for your mailing address in addition to your PO Box number. For example, if a Post Office is located at 500 Main Street and your PO Box is “PO Box 59”, with Street Addressing Service your mail may be addressed to you at “500 Main Street #59”. You may also use Street Addressing Service to receive packages that comply with USPS mailing standards deposited by private carriers, such as UPS, FedEx, DHL and Amazon. Both “street addressed” mail and PO Box addressed mail that comply with USPS mailing standards may be delivered to your PO Box. If a package does not fit inside your PO Box, you may retrieve it at the service window or from a parcel locker (options vary by location and package size and weight). 1. If you choose and pay for Street Addressing Service, your new street address format will be: ___________________________ # ______________ Post Office Street Address PO Box Number __________________________ _______ _______________________ City State PO Box ZIP Code 2. Please note that you must use the address format shown in No. 1 above. The address must include both the # sign and your PO Box number. For example, you may not use “Suite” or “Apt.” Mail sent to your PO Box that does not use address format shown in No. -

Changing Postal ZIP Code Boundaries

Order Code RL33488 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Changing Postal ZIP Code Boundaries June 23, 2006 Nye Stevens Specialist in American National Government Government and Finance Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Changing Postal ZIP Code Boundaries Summary Ever since the ZIP Code system for identifying address locations was devised in the 1960s, some citizens have wanted to change the ZIP Code to which their addresses are assigned. Because ZIP Codes are often not aligned with municipal boundaries, millions of Americans have mailing addresses in neighboring jurisdictions. This can cause higher insurance rates, confusion in voter registration, misdirected property and sales tax revenues for municipalities, and property value effects. Some communities that lack a delivery post office complain that the need to use mailing addresses of adjacent areas robs them of a community identity. Because the ZIP Code is the cornerstone for the U.S. Postal Service’s (USPS’s) mail distribution system, USPS long resisted changing ZIP Codes for any reason other than to improve the efficiency of delivery. Frustrated citizens frequently have turned to Members of Congress for assistance in altering ZIP Code boundaries. In the 101st Congress, a House subcommittee heard testimony from Members, city officials, and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) that USPS routinely denied local requests for adjusting ZIP Code boundaries in a peremptory manner. It considered three bills that would allow local governments to determine mailing addresses for their jurisdictions. Since then, USPS has developed a “ZIP Code Boundary Review Process” that promises “every reasonable effort” to consider and if possible accommodate municipal requests to modify the last lines of an acceptable address and/or ZIP Code boundaries. -

Postal Rates

• 2021/2022 • 2020/2021 Customer Care: 502 0860 111 www.postoffice.co.za CHURE RO BROCHURE B DID YOU 2021 / 2022 ... 1 APR. 21 - 31 MAR. 22 KNOW YOU ARE NOT ALLOWED TO TABLE OF CONTENTS POST THE FOLLOWING GOODS? Dangerous and Prohibited goods 1 Important Information 2 Ordinary Mail / Fast Mail 3-4 Postage Included Envelopes 4-5 Postcards 5 Domestic Stamp Booklets and Rolls 6 Packaging Products 6 Franking Machines 6-7 Domestic Registered Letter with Insurance Option 7-8 Mailroom Management 8 Direct Mail 9 Business Reply Services 9-10 InfoMail 10-12 Response Mail / Magmail 13-14 Domestic Parcel Service 14-15 International Mail 15-20 Expedited Mail Service 21-24 Philatelic Products 25 Postboxes, Private Bags and Accessories 25-26 (Valid 01 Jan to 31 Dec annually) Postbank 26 Speed Services Couriers 27-29 Tips to get your letter delivered on time, every time: 30 Contact Information / Complaints and Queries 31 DID YOU KNOW... YOU ARE NOT ALLOWED TO POST THE FOLLOWING GOODS? DANGEROUS AND PROHIBITED GOODS SCHEDULE OF DANGEROUS GOODS • Explosives – Ammunition, fireworks, igniters. • Compressed Gas – aerosol products, carbon dioxide gas, cigarette lighter, butane. • Flammable Liquids – alcohol, flammable paint thinners, flammable varnish removers, turpentine, petroleum products, benzene. • Flammable Solids – metallic magnesium, matches, zinc powder. • Oxidising material – some adhesives, some bleaching powders, hair or textiles dyes made of organic peroxides, fiberglass repair kits, chlorine. • Poison including Drugs and Medicine –although some are acceptable in prescription quantities, and non-infectious perishable biological substances are accepted when packed and transmitted appropriately RADIOACTIVE MATERIAL • Corrosives – corrosive cleaning liquid, paint or varnish removers, mercury filled thermometer • Miscellaneous – magnetized materials, oiled paper, polymerisable materials SCHEDULE OF PROHIBITED GOODS Bank notes – including all South African notes of whatever issue or denomination, and the bank notes or currency notes of any other country. -

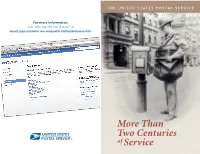

More Than Two Centuries of Service

THE UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE For more information, visit “Who We Are: Our History,” at about.usps.com/who-we-are/postal-history/welcome.htm. More Than Two Centuries of Service Number of Number of Pieces of Mail Number of Career Year Post Offices Income Expenses Pieces of Mail per Capita Delivery Points Employees (addresses) 1900 76,688 $102,353,579 $107,740,268 7,129,990,000 93.4 ---- ---- 1910 59,580 224,128,658 229,977,225 14,850,103,000 161.5 ---- ---- 1920 52,641 437,150,212 454,322,609 ---- ---- ---- ---- 1930 49,063 705,484,098 803,667,219 27,887,823,000 227.1 ---- 254,563 1940 44,024 766,948,627 807,629,180 27,749,467,000 210.8 ---- 266,076 1950 41,464 1,677,486,967 2,222,949,000 45,063,737,000 297.8 ---- 363,774 1960 35,238 3,276,588,433 3,873,952,908 63,674,604,000 355.1 ---- 408,987 1970 32,002 6,472,737,791 7,982,551,936 84,881,833,000 417.5 ---- 548,572 1980 30,326 18,752,915,000 19,412,587,000 106,311,062,000 469.3 ---- 536,373 1990 28,959 39,654,830,000 40,489,884,000 166,300,770,000 668.6 117,000,000 760,668 2000 27,876 64,540,000,000 62,992,000,000 207,882,200,000 738.7 134,500,000 787,538 150,900,000 583,908 75,426,000,000 170,859,000,000 553.4 2010 27,077 67,052,000,000 ess oduced nationwide eader) deployed introduced ® educed to one a day ders introduced national airmail service began ds issued ect Mail began experimentally ® began ® Code began ® United States Postal Service® began operations service subsidy (taxpayer dollars) General by the Continental Congr domestic money or Union) established ZIP+4 U.S. -

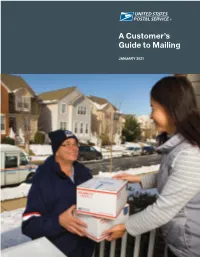

A Customer's Guide to Mailing

A Customer’s Guide to Mailing JANUARY 2021 Price List Notice 123, Price List, contains domestic and international Price List prices, and fees in a concise and accessible manner. Notice 123 • Effective January 24, 2021 Postal Explorer® pe.usps.com For current prices, see the Notice 123, Price List on Domestic Page International Page Postal Explorer at pe.usps.com. Flat Rate Pricing 3 Flat Rate Pricing 42 Retail Prices Retail Prices Priority Mail Express® 4 Global Express Guaranteed® 43 Priority Mail® 5 Priority Mail Express International® 44-45 First-Class Mail® 6 Priority Mail International Canada 46 First-Class Package Service—Retail™ 7 Priority Mail International® 47-48 USPS Retail Ground® 8-9 First-Class Mail International® 49 Media Mail® 10 First-Class Package International Service® 49 Library Mail 10 Airmail M-Bags 49 Commercial Prices Commercial Prices Priority Mail Express 11-12 Global Express Guaranteed 50-51 Priority Mail 12-15 Priority Mail Express International 52-55 First-Class Mail 16-17 Priority Mail International Canada 56-57 First-Class Package Service® 17 Priority Mail International 58-61 USPS Marketing Mail™ First-Class Package International Service 62 Letters 18-19 IPA® 63-64 Flats 20-21 ISAL® 65-66 Parcels 22-23 Country Price Groups 67 Parcel Select® 24-26 Media Mail 27 Services & Fees Library Mail 27 Extra Services and Fees 3 Bound Printed Matter 28-29 Parcel Return Service 30 Quick References Periodicals 31 International—Retail 4 Services & Fees Extra Services and Fees 32-33 Other Services 34-35 PO Boxes 36 Business Mailing Fees 37 Stationery 37 Address Management Systems 38-39 Quick References Domestic—Retail 40 Page 1 United States Postal Service Welcome 1 This guide will explain your options for mailing and help you choose the services that are best for you.