Introduction to a Future Scholarly Edition of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Fo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Maryallenfinal Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH SIX IMPOSSIBLE THINGS BEFORE BREAKFAST: THE LIFE AND MIND OF LEWIS CARROLL IN THE AGE OF ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND MARY ALLEN SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Kate Rosenberg Assistant Teaching Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Christopher Reed Distinguished Professor of English, Visual Culture, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Honors Adviser * Electronic approvals are on file. i ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes and offers connections between esteemed children’s literature author Lewis Carroll and the quality of mental state in which he was perceived by the public. Due to the imaginative nature of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, it has been commonplace among scholars, students, readers, and most individuals familiar with the novel to wonder about the motive behind the unique perspective, or if the motive was ever intentional. This thesis explores the intentionality, or lack thereof, of the motives behind the novel along with elements of a close reading of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. It additionally explores the origins of the concept of childhood along with the qualifications in relation to time period, culture, location, and age. It identifies common stereotypes and presumptions within the subject of mental illness. It aims to achieve a connection between the contents of Carroll’s novel with -

Children's Books & Illustrated Books

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 94 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #307 - ORIGINAL ART BY MAUD HUMPHREY FOR GALLANT LITTLE PATRIOTS #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus (The Doll House) #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus #195 - Detmold Arabian Nights #526 - Dr. Seuss original art #326 - Dorothy Lathrop drawing - Kou Hsiung (Pekingese) #265 - The Magic Cube - 19th century (ca. 1840) educational game Helen & Marc Younger Pg 3 [email protected] THE ITEMS IN THIS CATALOGUE WILL NOT BE ON RARE TUCK RAG “BLACK” ABC 5. ABC. (BLACK) MY HONEY OUR WEB SITE FOR A FEW WEEKS. -

PDF Download Jabberwocky and Other Nonsense: Collected Poems

JABBERWOCKY AND OTHER NONSENSE: COLLECTED POEMS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lewis Carroll | 464 pages | 31 Oct 2012 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141195940 | English | London, United Kingdom Jabberwocky and Other Nonsense: Collected Poems PDF Book It made a lot more sense reading it with the pictures acting it out, because most of the time, I had no idea what Carroll was saying with those crazy made up words. I won a prize and my poem was selected as the best out of all the primary schools in my home town. Added to basket. Hardback edition. The poems range from those written for friends and family, little girls he fancied, Oxford rhymes critiquing his university's politics some things never change , extracts from Wonderland, 'Phantasmagoria', 'The Hunting of the Snark', 'Sylvia and Bruno', and various miscellaneous. The poems are set out chronologically following a generous, thoughtful introduction from the esteemed Cambridge critic Gillian Beer. This edition is the first compiled collection of his poems, including both prominent and lesser known verses. Call us on or send us an email at. Read it Forward Read it first. Shelves: lawsonland , reread , poetry. I didn't really enjoy this collection. Grand Union. More filters. I feel if you can open a book at any page and read a random poem you would enjoy this book more. Hardback All in the golden afternoon Full leisurely we glide There is so much to love an We are building little homes on the sands And time does indeed flit away, burbling and chortling. The humor, sparkling wit and genius of this Victorian Englishman have lasted for more than a century. -

Cweb Study Guide

" " " " " Alice in Wonderland " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " STUDY " GUIDE " " Designed and developed" " " by: Lexi Barnett" " : Meet the Author Lewis Carrol Lewis Carroll was the pseudonym of Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a lecturer in mathematics at Christ Church, Oxford, who lived from 1832 to 1898. Carroll’s physical deformities, partial deafness, and irrepressible stammer made him an unlikely candidate for producing one of the most popular and enduring children’s fantasies in the English language. Carroll’s unusual appearance caused him to behave awkwardly around other adults, and his students at Oxford saw him as a stuffy and boring teacher. Underneath Carroll’s awkward exterior, however, lay a brilliant and imaginative artist. Carroll’s keen grasp of mathematics and logic inspired the linguistic humor and witty wordplay in his stories. Additionally, his unique understanding of children’s minds allowed him to compose imaginative fiction that appealed to young people. In 1856, Carroll and met the Liddell family. During their frequent afternoon boat trips on the river, Carroll told the Liddells fanciful tales. Alice quickly became Carroll’s favorite of the three girls, and he made her the subject of the stories that would later became Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. Almost ten years after first meeting the Liddells, Carroll compiled the stories and .1 submitted the completed manuscript for publication. pg If you lived all by yourself,Translating what would your housethe lookJabberwocky! like? Draw your ideal house below: There are many poems recited in Alice in Wonderland- one of the most bizarre is the Jabberwocky! What do you think it means? Write your translation of the words to the right of the poem " ’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe: All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. -

ALICE's ADVENTURES in WONDERLAND Lewis Carroll

The Jefferson Performing Arts Society Presents 1118 Clearview Parkway Metairie, LA 70001 504-885-2000 www.jpas.org 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Teacher’s Notes………………………..…………..…………..……..3 Standards and Benchmarks…………………..……………….…..5 Background………………………………………..…….………………6 Alice’s Adventures, Comparing and Contrasting ………… 12 Art, Math and Set Design: Alice in Minecraft Land...................................................33 The Science of Color Meets the White Rabbit and the March Hare...................74 Additional Resources…………………………………..…..….….106 2 | P a g e Teacher’s Notes Music and Lyrics by Sammy Fain and Bob Hilliard, Oliver Wallace and Cy Coban, Allie Wrubel and Ray Gilbert, Mack David, Al Hoffman and Jerry Livingston Music Adapted and Arranged and Additional Music and Lyrics by Bryan Louiselle Book Adapted and Additional Lyrics by David Simpatico Based on the 1951 Disney film, Alice in Wonderland, and the Lewis Carroll novels, "The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland" and "Through the Looking Glass," Lewis Carroll's famous heroine comes to life in this delightful adaptation of the classic Disney film. Lewis Carroll was the nom de plume of Charles L. Dodgson. Born on January 27, 1832 in Daresbury, Cheshire, England, Charles Dodgson wrote and created games as a child. At age 20 he received a studentship at Christ Church and was appointed a lecturer in mathematics. Dodgson was shy but enjoyed creating stories for children. Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry, linear and matrix algebra, mathematical logic, and recreational mathematics, producing nearly a dozen books under his real name. Dodgson also developed new ideas in linear algebra (e.g., the first printed proof of the Kronecker-Capelli theorem,) probability, and the study of elections (e.g., Dodgson's method); some of this work was not published until well after his death. -

The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, the Hunting of the Snark, a Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Online

yaTOs (Download pdf) The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Online [yaTOs.ebook] The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Pdf Free Lewis Carroll ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1419651 in Books 2011-11-07Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 1.70 x 6.50 x 9.30l, 1.70 #File Name: 0890097003440 pages | File size: 46.Mb Lewis Carroll : The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters): 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Wonderful books for a wonderful priceBy llamapyrLewis Carroll must've been the greatest children's book author of his time. I really admire his writing style and the creativity of his books, having grown up on them since I was 6. I've got a bunch of his novels in hardcover and paperback sitting on my shelves, so it seemed only right to add some digital versions to my library :)Anyway, I came here looking for Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass and found this set, and for a mere 99 cents it seemed worth a look. -

Lewis Carroll: Author, Mathematician, and Christian

Lewis Carroll: Author, Mathematician, and Christian David L. Neuhouser Mathematics Department Taylor University Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-1898), better known as Lewis Carroll, is best known as the creative and imaginative author of the Alice stories, but he was also a mathematician at Christ Church College, Oxford University and a devout Christian. His mathematics, especially mathematical logic, contributed much to the charming “nonsense” in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. However, his Christian thought is not evident in those books. In fact, they contain many parodies of morality poems for children. As a result of reading just these books, one might conclude that he was not even interested in morality. But to those who knew him personally, he seemed to be a rather pious, stodgy person. Also, he wrote essays and letters in defense of morality and Christianity as well as books and articles on mathematics. His writings on morality showed little of his literary imagination and his writings on mathematics give no indication of his Christianity. Only in Sylvie and Bruno and Sylvie and Bruno Concluded did Dodgson attempt to bring his literary creativity, mathematics, and Christianity all together in one artistic creation. This paper will attempt to answer the following questions. What motivated him to make this attempt and how successful was it? The Alice stories were the first really successful children’s stories which did not have obvious moral teachings. They were just for fun. However he wrote articles and letters against “indecent literature,” joking about sacred things, and immorality in plays. Some projects that he planned but never completed were: selections from the Bible to be memorized, selections from the Bible with pictures for children, and selections from Shakespeare with inappropriate content for young girls deleted. -

Alice Through the Looking-Glass Is Presented by Special Arrangement with the Estate of James Crerar Reaney

This production was originally produced at the Stratford Festival in association with Canada’s National Arts Centre in 2014. nov dec 26 19 2015 THEATRE FOR YOUNG AUDIENCES GENEROUSLY SUPPORTED BY STUDY GUIDE Adapted from the Stratford Festival 2014 Study Guide by Luisa Appolloni This production was originally produced at the Stratford Festival in association with Canada's National Arts Centre in 2014. Alice Through the Looking-Glass is presented by special arrangement with the Estate of James Crerar Reaney. 1 THEATRE ETIQUETTE “The theater is so endlessly fascinating because it's so accidental. It's so much like life.” – Arthur Miller Arrive Early: Latecomers may not be admitted to a performance. Please ensure you arrive with enough time to find your seat before the performance starts. Cell Phones and Other Electronic Devices: Please TURN OFF your cell phones/iPods/gaming systems/cameras. We have seen an increase in texting, surfing, and gaming during performances, which is very distracting for the performers and other audience members. The use of cameras and recording devices is strictly prohibited. Talking During the Performance: You can be heard (even when whispering!) by the actors onstage and the audience around you. Disruptive patrons will be removed from the theatre. Please wait to share your thoughts and opinions with others until after the performance. Food/Drinks: Food and hot drinks are not allowed in the theatre. Where there is an intermission, concessions may be open for purchase of snacks and drinks. There is complimentary water in the lobby. Dress: There is no dress code at the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre, but we respectfully reQuest that patrons refrain from wearing hats in the theatre. -

ARTICLE: Jan Susina: Playing Around in Lewis Carroll's Alice Books

Playing Around in Lewis Carroll’s Alice Books • Jan Susina Mathematician Charles Dodgson’s love of play and his need for rules came together in his use of popular games as part of the structure of the two famous children’s books, Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, he wrote under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. The author of this article looks at the interplay between the playing of such games as croquet and cards and the characters and events of the novels and argues that, when reading Carroll (who took a playful approach even in his academic texts), it is helpful to understand games and game play. Charles Dodgson, more widely known by his pseudonym Lewis Carroll, is perhaps one of the more playful authors of children’s literature. In his career, as a children’s author and as an academic logician and mathematician, and in his personal life, Carroll was obsessed with games and with various forms of play. While some readers are surprised by the seemingly split personality of Charles Dodgson, the serious mathematician, and Lewis Carroll, the imaginative author of children’s books, it was his love of play and games and his need to establish rules and guidelines that effectively govern play that unite these two seemingly disparate facets of Carroll’s personality. Carroll’s two best-known children’s books—Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking- Glass and What Alice Found There (1871)—use popular games as part of their structure. In Victoria through the Looking-Glass, Florence Becker Lennon has gone so far as to suggest about Carroll that “his life was a game, even his logic, his mathematics, and his singular ordering of his household and other affairs. -

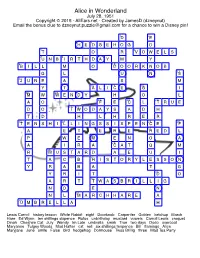

Alice in Wonderland

Alice in Wonderland July 28, 1951 Copyright © 2015 - AllEars.net - Created by JamesD (dzneynut) Email the bonus clue to [email protected] for a chance to win a Disney pin! 1 2 D E 3 4 H E D G E H O G D 5 6 T O R V O W E L S 7 8 U N B I R T H D A Y M Y 9 10 B I L L M O D O O R K N O B 11 G L U N S 12 J U N E A S M 13 14 15 Y T A L I C E G I 16 17 M W W E N D Y H O L 18 19 20 A O F E C L T R U E 21 22 D O T W O D A Y S A D H T D H L H R E R 23 24 25 26 T E N S H I L L I N G S S I X P E N C E F 27 A E T E R E R E D L 28 P W E M E N O A 29 A I R A C A T Q M 30 R M U S T A R D A E U I 31 T A C B H I S T O R Y L E S S O N Y R A B A T G 32 Y R I T D O 33 A R T T W A S B R I L L I G N O E N 34 N L M A R C H H A R E A 35 U M B R E L L A H Lewis Carroll history lesson White Rabbit eight Doorknob Carpenter Golden ketchup March Hare Ed Wynn ten shillings sixpence Rufus unbirthday mustard vowels Carroll Lewis croquet Dinah Cheshire Cat July Wendy Im Late umbrella smirk True two days Dodo overcoat Maryanne Tulgey Woods Mad Hatter cat red six shillings tenpence Bill flamingo Alice Maryjane June smile False bird hedgehog Dormouse Twas Brillig three Mad Tea Party ★ Thurl Ravenscroft, a member of the singing group, the Mellomen, who sing #27 Across, appears to have lost his head while singing a familiar song in what popular theme park attraction? (2 words) [HAUNTEDMANSION] Across Down 3. -

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland Alice in Wonderland (Movie) (Book) Similarities ______

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Chapter 12 ~ Page 1 © Gay Miller ~ Created by Gay Miller CHAPTER XII. Alice's Evidence 'Here!' cried Alice, quite forgetting in the flurry of the moment how large she had grown in the last few minutes, and she jumped up in such a hurry that she tipped over the jury-box with the edge of her skirt, upsetting all the jurymen on to the heads of the crowd below, and there they lay sprawling about, reminding her very much of a globe of goldfish she had accidentally upset the week before. 'Oh, I beg your pardon!' she exclaimed in a tone of great dismay, and began picking them up again as quickly as she could, for the accident of the goldfish kept running in her head, and she had a vague sort of idea that they must be collected at once and put back into the jury-box, or they would die. 'The trial cannot proceed,' said the King in a very grave voice, 'until all the jurymen are back in their proper places—all,' he repeated with great emphasis, looking hard at Alice as he said do. Alice looked at the jury-box, and saw that, in her haste, she had put the Lizard in head downwards, and the poor little thing was waving its tail about in a melancholy way, being quite unable to move. She soon got it out again, and put it right; 'not that it signifies much,' she said to herself; 'I should think it would be quite as much use in the trial one way up as the other.' As soon as the jury had a little recovered from the shock of being upset, and their slates and pencils had been found and handed back to them, they set to work very diligently to write out a history of the accident, all except the Lizard, who seemed too much overcome to do anything but sit with its mouth open, gazing up into the roof of the court. -

Phantasmagoria and Other Poems, by Charles Dodgson, AKA Lewis Carroll

www.freeclassicebooks.com Phantasmagoria and Other Poems, By Charles Dodgson, AKA Lewis Carroll www.freeclassicebooks.com 1 www.freeclassicebooks.com Contents PHANTASMAGORIA.................................................................................................................................3 CANTO I‐‐The Trystyng........................................................................................................................3 CANTO II‐‐Hys Fyve Rules....................................................................................................................6 CANTO III‐‐Scarmoges.........................................................................................................................8 CANTO IV‐‐Hys Nouryture.................................................................................................................11 CANTO V‐‐Byckerment......................................................................................................................14 CANTO VI‐‐Dyscomfyture..................................................................................................................17 CANTO VII‐‐Sad Souvenaunce...........................................................................................................20 ECHOES .................................................................................................................................................22 A SEA DIRGE ..........................................................................................................................................23