Chapter- Iii the Evolution of the Health Policy Upto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhist Forest Monasteries and Meditation Centres in Sri Lanka a Guide for Foreign Buddhist Monastics and Lay Practitioners

Buddhist Forest Monasteries and Meditation Centres in Sri Lanka A Guide for Foreign Buddhist Monastics and Lay Practitioners Updated: April 2018 by Bhikkhu Nyanatusita Introduction In Sri Lanka there are many forest hermitages and meditation centres suitable for foreign Buddhist monastics or for experienced lay Buddhists. The following information is particularly intended for foreign bhikkhus, those who aspire to become bhikkhus, and those who are experienced lay practitioners. Another guide is available for less experienced, short term visiting lay practitioners. Factors such as climate, food, noise, standards of monastic discipline (vinaya), dangerous animals and accessibility have been considered with regard the places listed in this work. The book Sacred Island by Ven. S. Dhammika—published by the BPS—gives exhaustive information regarding ancient monasteries and other sacred sites and pilgrimage places in Sri Lanka. The Amazing Lanka website describes many ancient monasteries as well as the modern (forest) monasteries located at the sites, showing the exact locations on satellite maps, and giving information on the history, directions, etc. There are many monasteries listed in this guides, but to get a general idea of of all monasteries in Sri Lanka it is enough to see a couple of monasteries connected to different traditions and in different areas of the country. There is no perfect place in samṃsāra and as long as one is not liberated from mental defilements one will sooner or later start to find fault with a monastery. There is no monastery which is perfectly quiet and where the monks are all arahants. Rather than trying to find the perfect external place, which does not exist, it is more realistic to be content with an imperfect place and learn to deal with the defilements that come up in one’s mind. -

Polonnaruwa Development Plan 2018-2030

POLONNARUWA URBAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2018-2030 VOLUME I Urban Development Authority District Office Polonnaruwa 2018-2030 i Polonnaruwa 2018-2030, UDA Polonnaruwa Development Plan 2018-2030 POLONNARUWA URBAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN VOLUME I BACKGROUND INFORMATION/ PLANNING PROCESS/ DETAIL ANALYSIS /PLANNING FRAMEWORK/ THE PLAN Urban Development Authority District Office Polonnaruwa 2018-2030 ii Polonnaruwa 2018-2030, UDA Polonnaruwa Development Plan 2018-2030 DOCUMENT INFORMATION Report title : Polonnaruwa Development Plan Locational Boundary (Declared area) : Polonnaruwa MC (18 GN) and Part of Polonnaruwa PS(15 GN) Gazette No : Client/ Stakeholder (shortly) : Local Residents, Relevent Institutions and Commuters Commuters : Submission date :15.12.2018 Document status (Final) & Date of issued: Author UDA Polonnaruwa District Office Document Submission Details Version No Details Date of Submission Approved for Issue 1 Draft 2 Draft This document is issued for the party which commissioned it and for specific purposes connected with the above-captioned project only. It should not be relied upon by any other party or used for any other purpose. We accept no responsibility for the consequences of this document being relied upon by any other party, or being used for any other purpose, or containing any error or omission which is due to an error or omission in data supplied to us by other parties. This document contains confidential information and proprietary intellectual property. It should not be shown to other parties without consent from the party -

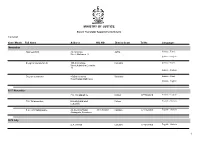

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10 -

CONTENTS Chapter Preface Introduction 1

CONTENTS Chapter Preface Introduction 1. Sri Lanka 2. Prehistoric Lanka; Ravana abducts Princess Sita from India.(15) 3 The Mahawamsa; The discovery of the Mahawamsa; Turnour's contribution................................ ( 17) 4 Indo-Aryan Migrations; The coming of Vijaya...........(22) 5. The First Two Sinhala Kings: Consecration of Vijaya; Panduvasudeva, Second king of Lanka; Princess Citta..........................(27) 6 Prince Pandukabhaya; His birth; His escape from soldiers sent to kill him; His training from Guru Pandula; Battle of Kalahanagara; Pandukabhaya at war with his uncles; Battle of Labu Gamaka; Anuradhapura - Ancient capital of Lanka.........................(30) 7 King Pandukabhaya; Introduction of Municipal administration and Public Works; Pandukabhaya’s contribution to irrigation; Basawakulama Tank; King Mutasiva................................(36) 8 King Devanampiyatissa; gifts to Emporer Asoka: Asoka’s great gift of the Buddhist Doctrine...................................................(39) 9 Buddhism established in Lanka; First Buddhist Ordination in Lanka around 247 BC; Mahinda visits the Palace; The first Religious presentation to the clergy and the Ordination of the first Sinhala Bhikkhus; The Thuparama Dagoba............................ ......(42) 10 Theri Sanghamitta arrives with Bo sapling; Sri Maha Bodhi; Issurumuniya; Tissa Weva in Anuradhapura.....................(46) 11 A Kingdom in Ruhuna: Mahanaga leaves the City; Tissaweva in Ruhuna. ...............................................................................(52) -

Holy Roman Empire

WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 1 V1V2 WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 CONTENT Historical Background Bohemian-Palatine War (1618–1623) Danish intervention (1625–1629) Swedish intervention (1630–1635) French intervention (1635 –1648) Peace of Westphalia SPECIAL RULES DEPLOYMENT Belligerents Commanders ARMY LISTS Baden Bohemia Brandenburg-Prussia Brunswick-Lüneburg Catholic League Croatia Denmark-Norway (1625-9) Denmark-Norway (1643-45) Electorate of the Palatinate (Kurpfalz) England France Hessen-Kassel Holy Roman Empire Hungarian Anti-Habsburg Rebels Hungary & Transylvania Ottoman Empire Polish-Lithuanian (1618-31) Later Polish (1632 -48) Protestant Mercenary (1618-26) Saxony Scotland Spain Sweden (1618 -29) Sweden (1630 -48) United Provinces Zaporozhian Cossacks BATTLES ORDERS OF BATTLE MISCELLANEOUS Community Manufacturers Thanks Books Many thanks to Siegfried Bajohr and the Kurpfalz Feldherren for the pictures of painted figures. You can see them and much more here: http://www.kurpfalz-feldherren.de/ Also thanks to the members of the Grimsby Wargames club for the pictures of painted figures. Homepage with a nice gallery this : http://grimsbywargamessociety.webs.com/ 2 V1V2 WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 3 V1V2 WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 The rulers of the nations neighboring the Holy Roman Empire HISTORICAL BACKGROUND also contributed to the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War: Spain was interested in the German states because it held the territories of the Spanish Netherlands on the western border of the Empire and states within Italy which were connected by land through the Spanish Road. The Dutch revolted against the Spanish domination during the 1560s, leading to a protracted war of independence that led to a truce only in 1609. -

Sri Lanka Island Tour (19 Days / 18 Nights)

Sri Lanka Island Tour (19 Days / 18 Nights) AIRPORT - NEGOMBO DAY 01 Arrival at the Bandaranayake International Airport, meet your driver/guide and transfer to the first hotel in Negombo by a luxury car. Visits: Colonial Dutch Fort Close to the seafront near the lagoon mouth are the ruins of the old Dutch fort, which has a fine gateway inscribed with the date 1678. Also there is a green, called the Esplanade, where cricket matches are a big attraction. As the fort grounds are now occupied by the town’s prison, the only way you’ll get a peek inside is by committing a serious crime. You’d need to be very interested in old Dutch architecture to go to such lengths. Dutch Canal The boat ride/safari that takes you along the colonial Dutch canal which runs through Waikkal, gives you snap shots of bird life, essentially comprising waders, stunning kingfishers, rare pied kingfishers, bee-eaters, Brahminy kites, etc. Water monitors, bearing an uncanny resemblance to crocodiles, are also bound to make an appearance, so keep your eye out for a glimpse! You can prolong your boat journey by following the canal onto the sea, where you can continue onwards to Negombo where you can stop at the town, do some shopping and return via boat to Waikkal. 2nd biggest Fish Market in Sri Lanka The Negombo Fishing Village, also known as the Lellama by the locals, is located across the lagoon bridge, near the Old Dutch Gate. The large open air fish market is the second largest in the country. -

Y%S ,Xld M%Cd;Dka;%Sl Iudcjd§ Ckrcfha .Eiü M;%H W;S Úfyi the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka EXTRAORDINARY

Y%S ,xld m%cd;dka;%sl iudcjd§ ckrcfha .eiÜ m;%h w;s úfYI The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka EXTRAORDINARY wxl 2072$58 - 2018 uehs ui 25 jeks isl=rdod - 2018'05'25 No. 2072/58 - FRIDAY, MAY 25, 2018 (Published by Authority) PART I : SECTION (I) — GENERAL Government Notifications SRI LANKA Coastal ZONE AND Coastal RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN - 2018 Prepared under Section 12(1) of the Coast Conservation and Coastal Resource Management Act, No. 57 of 1981 THE Public are hereby informed that the Sri Lanka Coastal Zone and Coastal Resource Management Plan - 2018 was approved by the cabinet of Ministers on 25th April 2018 and the Plan is implemented with effect from the date of Gazette Notification. MAITHRIPALA SIRISENA, Minister of Mahaweli Development and Environment. Ministry of Mahaweli Development and Environment, No. 500, T. B. Jayah Mawatha, Colombo 10, 23rd May, 2018. 1A PG 04054 - 507 (05/2018) This Gazette Extraordinary can be downloaded from www.documents.gov.lk 1A 2A I fldgi ( ^I& fPoh - YS% ,xld m%cd;dka;s%l iudcjd§ ckrcfha w;s úfYI .eiÜ m;%h - 2018'05'25 PART I : SEC. (I) - GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA - 25.05.2018 CHAPTER 1 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 THE SCOPE FOR COASTAL ZONE AND COASTAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT 1.1.1. Context and Setting With the increase of population and accelerated economic activities in the coastal region, the requirement of integrated management focused on conserving, developing and sustainable utilization of Sri Lanka’s dynamic and resources rich coastal region has long been recognized. -

2021 Schools Reseaved List.Pdf

Service AppNo Parent Name Child Name Address School ID School Name School Address Number 101/1 H 5, Kiw Rd,Police Quarters,Colombo 3098 Chandralatha NA Methsuwa HKTS 00045 ROYAL COLLEGE RAJAKEEYA MW, COLOMBO 07 02. 1675 Kulathunga KMMB 6488 Kulathunga KMDNB N-01, STF Quarters,Katukurunda,Kalutara. 00045 ROYAL COLLEGE RAJAKEEYA MW, COLOMBO 07 2115 Siriwardhana SNPK 40278 Siriwardhana SLMB 521/D,Mampe North,Piliyandala. 00045 ROYAL COLLEGE RAJAKEEYA MW, COLOMBO 07 0201 Hewage HLDW 6017 Hewage HKCM No 165/5,Iluppitiya Watta,Guruwala, Dompe. 00045 ROYAL COLLEGE RAJAKEEYA MW, COLOMBO 07 0752 Weerasinghe WPIU 61787 Weerasinghe WPAS Akkara vissa Rd,Koshena,Mirigama. 00045 ROYAL COLLEGE RAJAKEEYA MW, COLOMBO 07 1760 Amarasekara U 2041 Amarasekara NS 30/3,Egoda Uyana, OruwalaAthurugiriya. 00045 ROYAL COLLEGE RAJAKEEYA MW, COLOMBO 07 0746 Dulgala DSPK 39274 Dulgale DO No 186/2B,Church Rd,Gonawala. 00045 ROYAL COLLEGE RAJAKEEYA MW, COLOMBO 07 0750 Bandara BMM 54477 Bandara BMBMI 59/2,Sri Gnanendra Rd,Rathmalana. 00045 ROYAL COLLEGE RAJAKEEYA MW, COLOMBO 07 1675 Kulathunga KMMB 6488 Kulathunga KMDNB N-01, STF Quarters,Katukurunda,Kalutara. 00046 ANANDA COLLEGE COLOMBO 10 2115 Siriwardhana SNPK 40278 Siriwardhana SLMB 521/D,Mampe North,Piliyandala. 00046 ANANDA COLLEGE COLOMBO 10 0201 Hewage HLDW 6017 Hewage HKCM No 165/5,Iluppitiya Watta,Guruwala, Dompe. 00046 ANANDA COLLEGE COLOMBO 10 0752 Weerasinghe WPIU 61787 Weerasinghe WPAS Akkara vissa Rd,Koshena,Mirigama. 00046 ANANDA COLLEGE COLOMBO 10 1760 Amarasekara U 2041 Amarasekara NS 30/3,Egoda Uyana, OruwalaAthurugiriya. 00046 ANANDA COLLEGE COLOMBO 10 0746 Dulgala DSPK 39274 Dulgale DO No 186/2B,Church Rd,Gonawala. -

Section II: Periodic Report on the State of Conservation of the Ancient City

PERIODIC REPORTING EXERCISE ON THE APPLICATION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE CONVENTION SECTION II State of Conservation of specific World Heritage properties State Party: Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka Property Name: The Sacred City of Polonnaruva Periodic Reporting Exercise on the Application of the World Heritage Convention Section II: State of conservation of specific World Heritage properties - 2 - Periodic Reporting Exercise on the Application of the World Heritage Convention Section II: State of conservation of specific World Heritage properties - 3 - Periodic Reporting Exercise on the Application of the World Heritage Convention Section II: State of conservation of specific World Heritage properties II.1. Introduction a. Country (and State Party if different): Sri Lanka 001 b. Name of World Heritage property: Ancient City of Polonnaruva 002 c. In order to locate the property precisely, please attach a topographic map showing scale, 003 orientation, projection, datum, site name, date and graticule. The map should be an original print and not be trimmed. The site boundaries should be shown on the map. In addition they can be submitted in a detailed description, indicating topographic and other legally defined national, regional, or international boundaries followed by the site boundaries. The State Parties are encouraged to submit the geographic information in digital form so that it can be integrated into a Geographic Information System (GIS). On this questionnaire indicate the geographical co-ordinates to the nearest second (in the case of large sites, towns, areas etc., give at least 3 sets of geographical co-ordinates): Centre point: Point “A” at Parakramabahu Palace, lat 7. 94267, long 81. -

SOE 2010 Report

SRI LANKA State of the Economy 2009 INSTITUTE OF POLICY STUDIES 99, St. Michael’s Road, Colombo 3, Sri Lanka Copyright C September 2010 Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka ISBN 978-955-8708-55-2 National Library of Sri Lanka-Cataloguing-In-Publication Data Sri Lanka State of the Economy -- 2010 / Colombo : Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka, 2010 . --- 225 ; 21cm ISBN 978-955-8708-59-0 Price Rs. i. 330.95493 DDC 21 ii. Title 1. Economics - Sri Lanka Please address orders to: Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka 99 St Michael’s Road, Colombo 3, Sri Lanka Tel: +94 11 2431 368, 2431 378 Fax: +94 11 2431 395 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ips.lk This report was prepared by a team led by Dushni Weerakoon, with the guidance of Saman Kelegama, Executive Director, IPS. Contributing authors are Nisha Arunatilake, G.D. Dayaratne, Deshal de Mel, Ayodya Galappatige, Asha Gunawardena, Dilani Hirimuthugodage, Suwendrani Jayaratne, Ruwan Jayathilaka, Priyanka Jayawardena, Tilani Jayawardhana, Roshini Jayaweera, Haren Kodagoda, Malathy Knight-John, Sunimalee Madurawela, Wimal Nanayakkara, Nethmini Perera, Dharshani Premaratne, Parakrama Samarathunga, Athula Senaratne, Manoj Thibbotuwawa, Dushni Weerakoon, and Kanchana Wickremasinghe. Editorial support from Charmaine Wijesinghe and D.D.M Waidyasekera, and formatting support from Asuntha Paul is gratefully acknowledged. Contents Growth and Stability in Post-conflict Economic Recovery 1. Policy Perspectives 1 2. Growth and Stability in Post-conflict Economic Recovery 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Recovery and Growth 8 2.2.1 Employment 12 2.2.2 Savings and Investment 13 2.3 Fiscal Policy Management 14 2.3.1 Deficit Financing and Debt 16 2.3.2 Fiscal Policy and Macroeconomic Stability 19 2.4 Monetary Policy for Economic Recovery 20 2.4.1 The Impossible Trinity: Implications for Interest Rates and the Exchange Rate 22 2.5 External Sector: Current Account, Capital Flows and the Exchange Rate 24 2.5.1 'Dutch Disease' through a Post-conflict Lens 25 2.5.2 Capital Inflows and Official Reserves 27 2.6 Conclusion 28 3. -

Budget Proposals 2018 Budget with Pwc 2018 Building Relationships, Creating Value

Budget Proposals 2018 Budget with PwC 2018 Building relationships, Creating value $ $ $ $ $ Budget Proposals – 2018 10th November 2017 To Clients of PricewaterhouseCoopers Dear Client We are pleased to forward you a Summary and Analysis of the Budget Proposals for 2018, presented in the Parliament on 9th November 2017, by Hon Mangala Samaraweera, Minister of Finance and Media. We are also forwarding – • “Tax facts at a Glance”, together with a “Tax Calendar”, • Booklet on “Tax Update” If you would like further information on any of the taxation changes and other measures announced in the Budget, please do not hesitate to get in touch with us. Yours truly Hiranthi Ratnayake Director – Tax Services For and on behalf of PricewaterhouseCoopers (Private) Ltd PricewaterhouseCoopers (Private) Ltd., P. O. Box 918, 100 Braybrooke Place, Colombo 2, Sri Lanka T: +94 (11) 771 9838, 471 9838, F: +94 (11) 230 3197, www.pwc.com/lk Company Number: PV 3498 PricewaterhouseCoopers (Private) Ltd., is a member firm of PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited, each member firm of which is a separate legal entity. Who we are PwC is a network of firms in 158 countries with more than 236,000 people who are committed to delivering quality in assurance, advisory and tax services. PwC refers to the PwC network and/or one or more of its member firms, each of which is a separate legal entity. PwC Sri Lanka PwC Sri Lanka operates from its principle office in Colombo, the commercial capital of Sri Lanka and also overlooks the operations in Malé, the capital of the Republic of Maldives. With over 400 people and 19 Partners and Directors, we act as advisers to private sector enterprises and government on Assurance, Finance and Tax Advisory mandates, Technology Advisory.