Comparing Traditional and Modern Trends in Jazz Improvisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

The Dave Brubeck Quartet Jazz Impressions of the U.S.A. Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Dave Brubeck Quartet Jazz Impressions Of The U.S.A. mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Jazz Impressions Of The U.S.A. Country: US Released: 1957 Style: Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1449 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1503 mb WMA version RAR size: 1488 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 868 Other Formats: FLAC MOD AAC AU WMA MMF APE Tracklist A1 Ode To A Cowboy A2 Summer Song A3 Tea Down Yonder For Two A4 History Of A Boy Scout B1 Plain Song B2 Curtain Time B3 Sounds Of The Loop B4 Home At Last Credits Alto Saxophone – Paul Desmond Bass – Norman Bates Drums – Joe Morello Piano – Dave Brubeck Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Dave Jazz Impressions Of The CL 984 Columbia CL 984 US 1957 Brubeck Quartet U.S.A. (LP, Album, Mono) The Dave Jazz Impressions Of The CL 984 Columbia CL 984 US 1957 Brubeck Quartet U.S.A. (LP, Album, Mono) The Dave Jazz Impressions Of The Phoenix 131573 131573 US 2013 Brubeck Quartet U.S.A. (CD, RE, RM) Records The Dave Jazz Impressions Of The CL 984 Columbia CL 984 Canada 1957 Brubeck Quartet U.S.A. (LP, Album, Mono) Jazz Impressions Of The The Dave Gambit 69308 U.S.A. (CD, Album, Mono, RE, 69308 Europe 2009 Brubeck Quartet Records Unofficial) Related Music albums to Jazz Impressions Of The U.S.A. by The Dave Brubeck Quartet The Dave Brubeck Quartet - Anything Goes! The Dave Brubeck Quartet Plays Cole Porter The Dave Brubeck Quartet - Dave Brubeck At Storyville: 1954 (Vol. -

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

UT Jazz Jury Repertoire – 5/2/06 Afternoon in Paris 43 a Foggy Day

UT Jazz Jury Repertoire – 5/2/06 Level 1 Tunes JA Level 2 Tunes JA Level 3 Tunes JA Level 4 Tunes JA Afternoon in Paris 43 A Foggy Day 25 Alone Together 41 Airegin 8 All Blues 50 A Night in Tunisia 43 Anthropology (Thrivin’ from a Riff) 6 Along Came Betty 14 A Time for Love 40 Afro Blue 64 Blue in Green 50 Beyond All Limits 9 Autumn Leaves 54 All the Things You Are 43 Body and Soul 41 Blood Count 66 Blue Bossa 54 Angel Eyes 23 Ceora 106 Bolivia 35 But Beautiful 23 Bird Blues (Blues 4 Alice) 2 Chelsea Bridge 66 Brite Piece 19 C Jam Blues 48 Bluesette 43 Children of the Night 33 Cherokee 15 Cantaloupe Island (96) 54 But Not for Me 65 Come Rain or Come Shine 25 Clockwise 35 Cantaloupe Island (132) 11 Cottontail 48 Confirmation 6 Countdown 28 Days of Wine and Roses 40 Don’t Get Around Much Anymore48 Corcovado-Quiet Nights 98 Dolphin Dance 11 Doxy (134) 54 Easy Living 52 Desafinado (184) 74 E.S.P. 33 Doxy (92) 8 Everything Happens to Me 23 Desafinado (136) 98 Giant Steps 28 Freddie the Freeloader 50 Footprints 33 Donna Lee 6 I'll Remember April 43 For Heaven’s Sake 89 Four 7 Embraceable You 51 Infant Eyes 33 Georgia 49 Groovin’ High 43 Estate 94 Inner Urge 108 Honeysuckle Rose 71 Have You Met Miss Jones 25 Fee Fi Fo Fum 33 It’s You or No One 61 I Got It Bad 48 Here’s That Rainy Day 23 Goodbye 94 Joshua 50 Impressions (112) 54 How Insensitive 98 I Can’t Get Started 25 Katrina Ballerina 9 Impressions (224) 28 I Didn’t Know About You 48 I Mean You 56 Lament for Booker 60 Killer Joe 70 I Hear a Rhapsody 80 In Case You Haven’t Heard 9 Love for -

How Democratic Is Jazz?

Accepted Manuscript Version Version of Record Published in Finding Democracy in Music, ed. Robert Adlington and Esteban Buch (New York: Routledge, 2021), 58–79 How Democratic Is Jazz? BENJAMIN GIVAN uring his 2016 election campaign and early months in office, U.S. President Donald J. Trump was occasionally compared to a jazz musician. 1 His Dnotorious tendency to act without forethought reminded some press commentators of the celebrated African American art form’s characteristic spontaneity.2 This was more than a little odd. Trump? Could this corrupt, capricious, megalomaniacal racist really be the Coltrane of contemporary American politics?3 True, the leader of the free world, if no jazz lover himself, fully appreciated music’s enormous global appeal,4 and had even been known in his youth to express his musical opinions in a manner redolent of great jazz musicians such as Charles Mingus and Miles Davis—with his fists. 5 But didn’t his reckless administration I owe many thanks to Robert Adlington, Ben Bierman, and Dana Gooley for their advice, and to the staffs of the National Museum of American History’s Smithsonian Archives Center and the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Copyright © 2020 by Benjamin Givan. 1 David Hajdu, “Trump the Improviser? This Candidate Operates in a Jazz-Like Fashion, But All He Makes is Unexpected Noise,” The Nation, January 21, 2016 (https://www.thenation.com/article/tr ump-the-improviser/ [accessed May 14, 2019]). 2 Lawrence Rosenthal, “Trump: The Roots of Improvisation,” Huffington Post, September 9, 2016 (https://www.huffpost.com/entry/trump-the-roots-of-improv_b_11739016 [accessed May 14, 2019]); Michael D. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

The Solo Style of Jazz Clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 – 1938

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 The solo ts yle of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938 Patricia A. Martin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Patricia A., "The os lo style of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1948. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1948 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SOLO STYLE OF JAZZ CLARINETIST JOHNNY DODDS: 1923 – 1938 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music By Patricia A.Martin B.M., Eastman School of Music, 1984 M.M., Michigan State University, 1990 May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is dedicated to my father and mother for their unfailing love and support. This would not have been possible without my father, a retired dentist and jazz enthusiast, who infected me with his love of the art form and led me to discover some of the great jazz clarinetists. In addition I would like to thank Dr. William Grimes, Dr. Wallace McKenzie, Dr. Willis Delony, Associate Professor Steve Cohen and Dr. -

Shall We Stomp?

Volume 36 • Issue 2 February 2008 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. Shall We Stomp? The NJJS proudly presents the 39th Annual Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp ew Jersey’s longest Nrunning traditional jazz party roars into town once again on Sunday, March 2 when the 2008 Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp is pre- sented in the Grand Ballroom of the Birchwood Manor in Whippany, NJ — and you are cordially invited. Slated to take the ballroom stage for five hours of nearly non-stop jazz are the Smith Street Society Jazz Band, trumpeter Jon Erik-Kellso and his band, vocalist Barbara Rosene and group and George Gee’s Jump, Jivin’ Wailers PEABODY AT PEE WEE: Midori Asakura and Chad Fasca hot footing on the dance floor at the 2007 Stomp. Photo by Cheri Rogowsky. Story continued on page 26. 2008 Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp MARCH 2, 2008 Birchwood Manor, Whippany TICKETS NOW AVAILABLE see ad page 3, pages 8, 26, 27 ARTICLES Lorraine Foster/New at IJS . 34 Morris, Ocean . 48 William Paterson University . 19 in this issue: Classic Stine. 9 Zan Stewart’s Top 10. 35 Institute of Jazz Studies/ Lana’s Fine Dining . 21 NEW JERSEY JAZZ SOCIETY Jazz from Archives. 49 Jazzdagen Tours. 23 Big Band in the Sky . 10 Yours for a Song . 36 Pres Sez/NJJS Calendar Somewhere There’s Music . 50 Community Theatre. 25 & Bulletin Board. 2 Jazz U: College Jazz Scene . 18 REVIEWS The Name Dropper . 51 Watchung Arts Center. 31 Jazzfest at Sea. -

Download This List As PDF Here

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of 5.1 SACD, DVD-Audio and Blu-Ray Surround Discs JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow Dishwalla Services, State Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD Anderson, Jim Donna Byrne Licensed to Thrill SACD Anderson, Jim Jane Ira Bloom Sixteen Sunsets BD-A 2018 Grammy Winner: Anderson, Jim 2018 Jane Ira Bloom Early Americans BD-A Best Surround Album Wild Lines: Improvising on Emily Anderson, Jim 2020 Jane Ira Bloom DSD/DXD Download Dickinson Jazz Ambassadors/Sammy Anderson, Jim The Sammy Sessions BD-A Nestico Masur/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances BD-A Orchestra Anderson, Jim Patricia Barber Modern Cool BD-A SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2020 Patricia Barber Higher with Ulrike Schwarz Download SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2021 Patricia Barber Clique Download Svilvay/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Mortensen: Symphony Op. -

DP- Nov-Déc-17-18.Indd

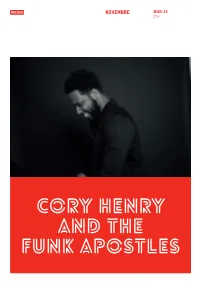

musique NOVEMBRE JEUDI 23 20H CORY HENRY AND THE FUNK APOSTLES / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Orgues, claviers Cory Henry Claviers Nicholas Semrad Guitare Adam Agati Andrew Bailey Batterie Darius Woodley Basse Sharay Reed Voix Cassondra James Matia Celeste © X-DR Cory Henry est le nouveau phénomène des claviers. Organiste, pianiste, compositeur, arran- geur, le claviériste des Snarky Puppy revisite les classiques de la soul et du funk avec une énergie communicative. Il forge un son totalement novateur aux confins du gospel, du funk et du jazz. À moins de 30 ans, il peut déjà revendiquer une longue carrière, marquée par des collaborations avec Kenny Garrett, Lalah Hathaway, The Roots, Bruce Springsteen... Reconnu pour son jeu d’orgue aux harmonies très riches, il puise son inspiration dans le jeu virtuose des pianistes Art Tatum ou encore Oscar Peterson. Les figures de Jimmy Smith, Marvin Gaye ou encore Prince ne sont jamais loin. Il capte l’essence même du jazz et du gospel et crée, à partir de ces deux composantes, une musique rayonnante au service du lyrisme et d’une grande construction narrative. En concert Cory Henry and The Funk Apostles enchaînent les Production Loop productions. grooves funk mêlés aux influences électriques de la soul, du jazz fusion et de l’électro. On savoure d’avance le plaisir de vous les faire découvrir sur notre scène après un passage / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / remarqué à Jazz à Vienne ! BIOGRAPHIE Cory Henry est un musicien multi-instrumentiste et producteur au CV étonnamment bien rempli pour son âge. Il joue principalement de l’orgue, depuis l’âge de deux ans. A 6 ans, il participe a un concours à l’Apollo Theater et se hisse jusqu’à la finale. -

Brazil and Switzerland Plays Together to Celebrate Music

BRAZIL AND SWITZERLAND PLAYS TOGETHER TO CELEBRATE MUSIC At the end of May 2016 an alliance between Brazil and Switzerland aims to conquer Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, starting May 25 th . Both cities will host sessions joining Brazilian and foreign musicians during Switzerland meets Brazil. The event presented by Swissando and Montreux Jazz Festival , will have performances by bands Nação Zumbi and The Young Gods, as well as concerts at the Swissando Jazz Club, this place is inspired by the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland, which celebrates its 50 the edition this year, featuring emerging talents and icons from the Brazilian scene. “Music is a great way to celebrate friendship between countries. Thanks to the Montreux Jazz Festival and its founder, Claude Nobs, Brazilian music is well known in Switzerland and in Europe. Brazilian musicians having been invited there almost since the beginning of the Festival. Joining our forces here for this project is a perfect match!” says André Regli, Swiss Ambassador in Brazil. The most important meeting takes place on May 26 th at Cine Joia in São Paulo, and on the 27 th, at Circo Voador, in Rio, with a joint performance between Brazilian band Nação Zumbi and Swiss group The Young Gods. The show will be a taste of what they are preparing for the 50 th edition of the Montreux Jazz Festival, which will take place in July in Switzerland. Besides the meeting of the two bands, who go through Circo Voador during Switzerland meets Brazil, will be able to see an exhibition honoring some Jazz Festival Montreux icons, including Brazilian legend. -

Second Wind: a Tribute to E Music of Bill Evans

Chuck Israels Jazz Orchestra contribution to Evans’ body of work. Second Wind: A Tribute To e Music Israels, of course, was the replacement for the Of Bill Evans legendary Scott LaFaro, who died in a car accident SOULPATCH in 1961, the loss of a friend and creative partner ++++ ½ that had devastated Evans. Eventually he found his footing with Israels, who had worked with As the famous album title has it, everybody digs Bill Evans. a who’s who of greats including Billie Holiday, But not everybody has su#ciently dug Chuck Israels, Evans’ Benny Goodman, Coleman Hawkins and John great, underappreciated bassist from his second trio (1962– Coltrane. Besides being a brilliant technician with 1966). is album, Israels’ return to full-time performing a wonderful round tone, Israels was an exquisitely aer a 30-year teaching career, should win him new fans for sensitive musical partner who helped bring out the his prodigious skills as both arranger and bassist, even as it best in the introspective Evans. Aer his stint with serves to remind longtime Evans devotees of his signi!cant Evans, Israels studied composition and arrang- ing with Hall Overton, who arranged elonious Monk compositions for a tentet at Monk’s tri- umphant 1959 Town Hall concert. Later, Israels became a pioneer of the jazz repertory movement, founding and leading the National Jazz Ensemble from 1973 to 1981. Although Israels has played Evans tunes with others (notably Danish pianist omas Clausen on the excellent 2003 trio album For Bill ), this is the !rst time he has orchestrated a whole album of songs associated with or inspired by Evans for a larger ensemble.