“One Line Flows, Yeah I Got Some of Those”: Genre, Tradition, and the Reception of Rhythmic Regularity in Grime Flow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nick Cage Direction

craft production just because of what it does with sampling technology and that alone. It’s got quite a conservative form and quite a pop form as well just at the moment, in terms of the clarity of the sonics. When those elements are added to hip-hop tracks it must be difficult to make the vocal stand out. The biggest challenge is always getting the vocal heard on top of the track — the curse of the underground is an ill-defined vocal. When I went to bigger studios and used 1176s and LA2s it was a revelation, chucking one of them on gets the vocal up a bit. That’s how we were able to blag our way through Dizzee’s first album. What do you use in Dizzee’s vocal chain? With the budget we were on when I did Boy In Da Corner I used a Neumann TLM103B. When I bought it, £500 seemed a hell of a lot of money for a microphone. Then it goes to my Drawmer 1960 — I exchanged a couple of my keyboards for that. Certainly with Showtime, the new desk improved the vocal sound. It would be interesting to just step the gear up a notch, now we have the deal with XL, and see what happens. Do you have a label deal for Dirty Stank records with XL? I Love You came out first on Dirty Stank on the underground, plus other tunes like Ho and some beats. XL has licensed the albums from Dirty Stank so it’s not a true label deal in that sense, although with our first signings, it’s starting to move in that Nick Cage direction. -

Statesman, V.49, N. 50.PDF

the stony brook Statesman -.~---~~~'---------------~~--~~-~---~- - ------- I--- ~~~---~--I-I---1- VOLUME XLIX, ISSUE 48 THURSDAY MAY 4, 2006 PUBLISHED TWICE WEEKLY Campus Wide UREA Celebration Impresses A L' Inits 5tn year, tne annuai celeoration or unaergraduate researcn and creativity was neic last week. URECA Celebration photos: ©John Griffin/Media Services Photography, Art Show photos: ©Jeanne Neville/Media Services Photography BY Sunr RAMBHIA and Sociology." Kudos goes to the Department of Bio- News Editor medical Engineering, which had the greatest number of abstract submissions, 25 in total. Last week, students had the opportunity to attend The main event of the Celebration was an ,all day the annual SBU Celebration of Undergraduate Research poster presentation session where students and faculty and Creativity. The event featured the work of students. were able to see type of research that goes on across involved in undergraduate research as well as activities campus all throughout the year. Some of the other in the arts. According to a recent press release issued by featured events included symposia held concurrently Karen Kernan, the Director of Programs for Research and by the Departments of English, History, and Psychology Creative Activity (as a part of the Office of the Provost), involving student oral presentations. Also,the College there were over 225 abstracts compiled in this year's. of Engineering and Applied Sciences held its annual book of Collected Abstracts. senior design conference comprising the two best senior the day's events to a close, the purpose and scope of the These 225 project descriptions represented over 300 design projects from each of the four major engineer- Celebration of Undergraduate and Creative Activities undergraduates in the various departments of"Anesthe- ing departments, Biomedical Engineering, Electrical was clear. -

England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 25 22.06.2019

22.06.2019 England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 25 Pos Vorwochen Woc BP Titel und Interpret 2019 / 25 - 1 11151 5 I Don't Care . Ed Sheeran & Justin Bieber 222121 2 Old Town Road . Lil Nas X 333241 7 Someone You Loved . Lewis Capaldi 44471 2 Vossi Bop . Stormzy 555112 Bad Guy . Billie Eilish 67764 Hold Me While You Wait . Lewis Capaldi 78896 SOS . Avicii feat. Aloe Blacc 8 --- --- 1N8 No Guidance . Chris Brown feat. Drake 99939 Cross Me . Ed Sheeran feat. Chance The Rapper & PnB Rock 10 11 11 1110 All Day And Night . Jax Jones & Martin Solveig pres. Europa . 11 10 10 69 If I Can't Have You . Shawn Mendes 12 --- 14 309 Grace . Lewis Capaldi 13 15 --- 213 Shine Girl . MoStack feat. Stormzy 14 13 --- 213 Never Really Over . Katy Perry 15 24 39 315 Wish You Well . Sigala & Becky Hill 16 17 13 73 Me! . Taylor Swift feat. Brendon Urie Of Panic! At The Disco 17 6 6 132 Piece Of Your Heart . Meduza feat. Goodboys 18 --- --- 1N18 Mad Love . Mabel 19 --- --- 1N19 Stinking Rich . MoStack feat. Dave & J Hus 20 --- --- 1N20 Heaven . Avicii . 21 22 18 318 The London . Young Thug feat. J. Cole & Travi$ Scott 22 --- --- 1N22 Shockwave . Liam Gallagher 23 30 31 323 One Touch . Jesse Glynne & Jax Jones 24 27 23 618 Guten Tag . Hardy Caprio & DigDa T 25 14 --- 214 What Do You Mean . Skepta feat. J Hus 26 43 48 1526 Ladbroke Grove . AJ Tracey 27 34 29 327 Easier . 5 Seconds Of Summer 28 18 47 518 Greaze Mode . -

Special Issue

ISSUE 750 / 19 OCTOBER 2017 15 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Post Malone scored Leave A Light On Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 with “sneaky” Tom Walker YouTube scheme. Relentless Records (Fader) out now Tom Walker is enjoying a meteoric rise. His new single Leave } Spotify moves A Light On, released last Friday, is a brilliant emotional piano to formalise pitch led song which builds to a crescendo of skittering drums and process for slots in pitched-up synths. Co-written and produced by Steve Mac 1 as part of the Brit List. Streaming support is big too, with top CONTENTS its Browse section. (Ed Sheeran, Clean Bandit, P!nk, Rita Ora, Liam Payne), we placement on Spotify, Apple and others helping to generate (MusicAlly) love the deliberate sense of space and depth within the mix over 50 million plays across his repertoire so far. Active on which allows Tom’s powerful vocals to resonate with strength. the road, he is currently supporting The Script in the US and P2 Editorial: Paul Scaife, } Universal Music Support for the Glasgow-born, Manchester-raised singer has will embark on an eight date UK headline tour next month RotD at 15 years announces been building all year with TV performances at Glastonbury including a London show at The Garage on 29 November P8 Special feature: ‘accelerator Treehouse on BBC2 and on the Today Show in the US. before hotfooting across Europe with Hurts. With the quality Happy Birthday engagement network’. Recent press includes Sunday Times Culture “Breaking Act”, of this single, Tom’s on the edge of the big time and we’re Record of the Day! (PRNewswire) The Sun (Bizarre), Pigeons & Planes, Clash, Shortlist and certain to see him in the mix for Brits Critics’ Choice for 2018. -

Admissions Report Shows Black Student Applications Only 1/3 Of

Dizzee New Heights The Rascal returns: an interview with the man who fixed up, and looks sharp - Page 8 No. 616 The Independent Cambridge Student Newspaper since 1947 Friday February 25, 2005 ll we Bar Admissions report y shows black student Luc applications only 1/3 of national average Sam Richardson there is an increasing emphasis on year. Whilst this week’s admis- the outreach work done by sions figures have shown some TWO YEARS after Varsity first Colleges and Departments in improvement, it is clear that highlighted the scarcity of black educational enrichment, through there is much more to be done to students in Cambridge, there are the provision of masterclasses, encourage black students to still fewer black undergraduates study days and a myriad of excel- apply to Cambridge.” at the University than there are lent online resources.” Pav Akhtar, the NUS’s Black students or academics with the Nikhil Gomes, co-ordinator Students’ Officer, said that surname White. of GEEMA (Group to “When I went to Cambridge Last year’s admissions statistics, Encourage Ethnic Minority from a working class background which were revealed this week, Applications) said that the prob- it was a complete culture shock. show that only 1.4% of students lem with attracting black stu- Black students can often feel iso- who applied to Cambridge were dents to Cambridge lies in the lated”. The BBC documentary black. This is less than a third of perceptions of the University Black Ambition, which followed a the national average, and margin- both nationally and internation- number of black Cambridge stu- ally lower than Oxford. -

Liverpool Philharmonic Announces Winner of Christopher Brooks Composition Prize 2018 in Association with the Rushworth Foundatio

Press Release IMMEDIATE: Thursday 12 October 2018 Liverpool Philharmonic Announces Winner of Christopher Brooks Composition Prize 2018 in association with the Rushworth Foundation and Lancashire Sinfonietta Legacy Fund Liverpool Philharmonic is delighted to announce 22-year-old Carmel Smickersgill as the winner of its annual Christopher Brooks Composition Prize in association with The Rushworth Foundation and Lancashire Sinfonietta Legacy Fund Carmel wins a cash prize of £1,000 made possible through the support of the Lancashire Sinfonietta Legacy Fund and The Rushworth Foundation and a year’s complimentary membership of the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers & Authors (BASCA). All three organisations are supporting the competition for a fourth year running. The Christopher Brooks Composition Prize provides Carmel with a unique opportunity over the next year to develop her talent. Carmel will be supported with a bespoke programme of workshops, masterclasses and mentoring sessions from resident and visiting musicians, conductors, composers, performers and other industry professionals associated with Liverpool Philharmonic. Carmel’s year will culminate in her writing a new work for performance by Ensemble 10/10, the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra’s new music group, which will be premiered in autumn 2019. Carmel will also develop her composition and teaching practice through access to Liverpool Philharmonic’s programme for children and young people, including Liverpool Philharmonic Youth Company, Youth Orchestra and Choirs, higher education partnerships and the transformative In Harmony Liverpool programme in Everton. Carmel is a composer based in Manchester having recently finished an undergraduate degree in composition with Gary Carpenter at the RNCM. Her music has been performed on Radio 3. -

The 2015 Brit Awards the Brit Awards 2015 in Association with Mastercard Were Held for the Fifth Year Running at the 02, London

PRODUCTION PROFILE: The BRIT Awards THE 2015 BRIT AWARDS THE BRIT AWARDS 2015 IN ASSOCIATION WITH MASTERCARD WERE HELD FOR THE FIFTH YEAR RUNNING AT THE 02, LONDON. WITH A SET DESIGN BY ES DEVLIN BUILT BY STEEL MONKEY. A HOST OF OTHER TOP SUPPLIERS INCLUDING LIGHT INITIATIVE, BRITANNIA ROW, PRG, OUTBACK RIGGING, STAGECO AND STRICTLY FX ENABLED THIS CHALLENGING SHOW TO HAPPEN. PRESENTED BY TV FAVOURITES ANT & DEC, THE AWARDS FEATURED LIVE PERFORMANCES FROM NINE GLOBAL SUPERSTARS CULMINATING IN A GRAND FINALE FROM MADONNA, HER FIRST APPEARANCE AT THE BRIT AWARDS FOR 20 YEARS. SIMON DUFF REPORTS ON A NIGHT OF AMBITION AND COURAGE. The trophy for 2015 BRIT Awards was and Lisa Shenton of Papilo Productions, read: ‘congratulations on your talent, on your designed by British artist Tracey Emin who is to manage the production of the event, life - on everything you give to others - thank famed for her innovative conceptual art. A contracted on behalf of the BPI. Other you’, were almost invisibly arrayed above the bold and triumphant design, it set the tone key suppliers included Steel Monkey, Eat stage and audience. Bryn Williams, Managing for this year’s main event, which included Your Hearts Out, Show & Event Security, Director for Light Initiative: “There were a a 36-metre wide video screen. A total of Showstars, Stage Miracles, Oglehog and number of practical issues we had to confront 14 large neon writing signs - inspired by Lovely Things. when delivering this project,” he explained. Emin’s work - were brought into the room LED powerhouse, Light Initiative, worked “Our biggest challenges were time constraints by Es Devlin’s bold design, hung over the in collaboration with scenery builders Steel and the scale of the project itself. -

3/30/2021 Tagscanner Extended Playlist File:///E:/Dropbox/Music For

3/30/2021 TagScanner Extended PlayList Total tracks number: 2175 Total tracks length: 132:57:20 Total tracks size: 17.4 GB # Artist Title Length 01 *NSync Bye Bye Bye 03:17 02 *NSync Girlfriend (Album Version) 04:13 03 *NSync It's Gonna Be Me 03:10 04 1 Giant Leap My Culture 03:36 05 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Jucxi So Confused 03:35 06 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Naila Boss It Can't Be Right 03:26 07 2Pac Feat. Elton John Ghetto Gospel 03:55 08 3 Doors Down Be Like That 04:24 09 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:54 10 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:53 11 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 03:52 12 3 Doors Down When Im Gone 04:13 13 3 Of A Kind Baby Cakes 02:32 14 3lw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 04:19 15 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 03:12 16 4 Strings (Take Me Away) Into The Night 03:08 17 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot 03:12 18 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 03:21 19 50 Cent Disco Inferno 03:33 20 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 21 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 03:57 22 50 Cent P.I.M.P. 04:15 23 50 Cent Wanksta 03:37 24 50 Cent Feat. Nate Dogg 21 Questions 03:41 25 50 Cent Ft Olivia Candy Shop 03:26 26 98 Degrees Give Me Just One Night 03:29 27 112 It's Over Now 04:22 28 112 Peaches & Cream 03:12 29 220 KID, Gracey Don’t Need Love 03:14 A R Rahman & The Pussycat Dolls Feat. -

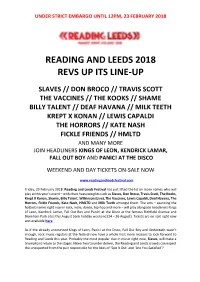

Reading and Leeds 2018 Revs up Its Line-Up

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 READING AND LEEDS 2018 REVS UP ITS LINE-UP SLAVES // DON BROCO // TRAVIS SCOTT THE VACCINES // THE KOOKS // SHAME BILLY TALENT // DEAF HAVANA // MILK TEETH KREPT X KONAN // LEWIS CAPALDI THE HORRORS // KATE NASH FICKLE FRIENDS // HMLTD AND MANY MORE JOIN HEADLINERS KINGS OF LEON, KENDRICK LAMAR, FALL OUT BOY AND PANIC! AT THE DISCO WEEKEND AND DAY TICKETS ON-SALE NOW www.readingandleedsfestival.com Friday, 23 February 2018: Reading and Leeds Festival has just lifted the lid on more names who will play at this year’s event – with chart heavyweights such as Slaves, Don Broco, Travis Scott, The Kooks, Krept X Konan, Shame, Billy Talent, Wilkinson (Live), The Vaccines, Lewis Capaldi, Deaf Havana, The Horrors, Fickle Friends, Kate Nash, HMLTD and Milk Teeth amongst them. The acts – spanning the hottest names right now in rock, indie, dance, hip-hop and more – will play alongside headliners Kings of Leon, Kendrick Lamar, Fall Out Boy and Panic! at the Disco at the famous Richfield Avenue and Bramham Park sites this August bank holiday weekend (24 – 26 August). Tickets are on-sale right now and available here. As if the already announced Kings of Leon, Panic! at the Disco, Fall Out Boy and Underøath wasn’t enough, rock music regulars at the festival now have a whole host more reasons to look forward to Reading and Leeds this year. Probably the most popular duo in music right now, Slaves, will make a triumphant return to the stages. Never two to under deliver, the Reading and Leeds crowds can expect the unexpected from the pair responsible for the likes of ‘Spit It Out’ and ‘Are You Satisfied’? UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 With another top 10 album, ‘Technology’, under their belt, Don Broco will be joining the fray this year. -

John Zorn Artax David Cross Gourds + More J Discorder

John zorn artax david cross gourds + more J DiSCORDER Arrax by Natalie Vermeer p. 13 David Cross by Chris Eng p. 14 Gourds by Val Cormier p.l 5 John Zorn by Nou Dadoun p. 16 Hip Hop Migration by Shawn Condon p. 19 Parallela Tuesdays by Steve DiPo p.20 Colin the Mole by Tobias V p.21 Music Sucks p& Over My Shoulder p.7 Riff Raff p.8 RadioFree Press p.9 Road Worn and Weary p.9 Bucking Fullshit p.10 Panarticon p.10 Under Review p^2 Real Live Action p24 Charts pJ27 On the Dial p.28 Kickaround p.29 Datebook p!30 Yeah, it's pink. Pink and blue.You got a problem with that? Andrea Nunes made it and she drew it all pretty, so if you have a problem with that then you just come on over and we'll show you some more of her artwork until you agree that it kicks ass, sucka. © "DiSCORDER" 2002 by the Student Radio Society of the Un versify of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circulation 17,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN ilsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money ordei payable to DiSCORDER Magazine, DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the December issue is Noven ber 13th. Ad space is available until November 27th and can be booked by calling Steve at 604.822 3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. -

Grime + Gentrification

GRIME + GENTRIFICATION In London the streets have a voice, multiple actually, afro beats, drill, Lily Allen, the sounds of the city are just as diverse but unapologetically London as the people who live here, but my sound runs at 140 bpm. When I close my eyes and imagine London I see tower blocks, the concrete isn’t harsh, it’s warm from the sun bouncing off it, almost comforting, council estates are a community, I hear grime, it’s not the prettiest of sounds but when you’ve been raised on it, it’s home. “Grime is not garage Grime is not jungle Grime is not hip-hop and Grime is not ragga. Grime is a mix between all of these with strong, hard hitting lyrics. It's the inner city music scene of London. And is also a lot to do with representing the place you live or have grown up in.” - Olly Thakes, Urban Dictionary Or at least that’s what Urban Dictionary user Olly Thake had to say on the matter back in 2006, and honestly, I couldn’t have put it better myself. Although I personally trust a geezer off of Urban Dictionary more than an out of touch journalist or Good Morning Britain to define what grime is, I understand that Urban Dictionary may not be the most reliable source due to its liberal attitude to users uploading their own definitions with very little screening and that Mr Thake’s definition may also leave you with more questions than answers about what grime actually is and how it came to be. -

England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 52 28.12.2019

28.12.2019 England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 52 Pos Vorwochen Woc BP Titel und Interpret 2019 / 52 - 1 1 --- --- 1N1 1 I Love Sausage Rolls . LadBaby 22342 Own It . Stormzy feat. Ed Sheeran & Burna Boy 34252 Before You Go . Lewis Capaldi 43472 Don't Start Now . Dua Lipa 5713922 Last Christmas . Wham! 6 --- --- 1N6 Audacity . Stormzy feat. Headie One 75575 Roxanne . Arizona Zervas 8681052 All I Want For Christmas Is You . Mariah Carey 9 --- --- 1N9 Lessons . Stormzy 10 1 1 201 11 Dance Monkey . Tones And I . 11 8 14 48 River . Ellie Goulding 12 11 --- 211 Adore You . Harry Styles 13 9 6 53 Everything I Wanted . Billie Eilish 14 14 22 1082 Fairytale Of New York . The Pogues & Kirsty McColl 15 12 11 296 Bruises . Lewis Capaldi 16 16 26 751 2 Merry Christmas Everyone . Shakin' Stevens 17 15 23 781 5 Do They Know It's Christmas ? . Band Aid 18 47 55 518 Watermelon Sugar . Harry Styles 19 24 39 3910 Step Into Christmas . Elton John 20 17 12 312 Blinding Lights . The Weeknd . 21 19 18 1314 Hot Girl Bummer . Blackbear 22 21 15 93 Lose You To Love Me . Selena Gomez 23 23 20 1020 Pump It Up . Endor 24 25 32 347 It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas . Michael Bublé 25 29 43 283 One More Sleep . Leona Lewis 26 35 40 426 Falling . Trevor Daniel 27 51 --- 3210 Lucid Dreams . Juice WRLD 28 31 33 2813 Santa Tell Me . Ariana Grande 29 34 44 804 I Wish It Could Be Christmas Everyday .