Digital Teaching and Learning a Language: One-To-One English Lessons on Skype

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

API 101: Modern Technology for Creating Business Value a Guide to Building and Managing the Apis That Empower Today’S Organizations

API 101: Modern technology for creating business value A guide to building and managing the APIs that empower today’s organizations WHITE PAPER WHITE PAPER API 101: Modern technology for creating business value Contents The modern API: What it is and why you need it 3 The conduit of digital ecosystems 3 The seismic change in the API landscape 3 iPaaS: A better way to build APIs 4 Quick API primer 4 A superior alternative 5 The API Integration Maturity Curve 5 Modern API management: Where are you on the maturity curve? 6 User profiles and requirements 6 How to determine API and management requirements 7 Overview of API creation and management requirements 8 From here to modernity: A checklist for API longevity 9 The components of a modern, manageable architecture 9 Case Study | TBWA Worldwide 10 SnapLogic: A unified integration platform 10 2 WHITE PAPER API 101: Modern technology for creating business value The modern API: What it is Digital deposits in consumer mobile banking provide a perfect example of a digital ecosystem in action. No longer and why you need it do customers need to trek to a branch office to deposit Application programming interface, or API as it’s universally a paper check. They can now open the bank app, take a referred to, is a technology almost as old as software itself, picture of the front and back of the check, specify the designed to allow data to flow between different applications. amount and, somewhat magically, money is transferred Today, modern APIs enable much more than inter-application into the customer’s account within a day. -

Investing in Equitable News and Media Projects

Investing in Equitable News and Media Projects Photo credit from Left to Right: Artwork: “Infinite Essence-James” by Mikael Owunna #Atthecenter; Luz Collective; Media Development Investment Fund. INVESTING IN EQUITABLE NEWS AND MEDIA PROJECTS AUTHORS Andrea Armeni, Executive Director, Transform Finance Dr. Wilneida Negrón, Project Manager, Capital, Media, and Technology, Transform Finance ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Farai Chideya, Ford Foundation Jessica Clark, Dot Connector Studio This work benefited from participation in and conversations at the Media Impact Funders and Knight Media Forum events. The authors express their gratitude to the organizers of these events. ABOUT TRANSFORM FINANCE Transform Finance is a nonprofit organization working at the intersection of social justice and capital. We support investors committed to aligning their impact investment practice with social justice values through education and research, the development of innovative investment strategies and tools, and overall guidance. Through training and advisory support, we empower activists and community leaders to shape how capital flows affect them – both in terms of holding capital accountable and having a say in its deployment. Reach out at [email protected] for more information. THIS REPORT WAS PRODUCED WITH SUPPORT FROM THE FORD FOUNDATION. Questions about this report in general? Email [email protected] or [email protected]. Read something in this report that you’d like to share? Find us on Twitter @TransformFin Table of Contents 05 I. INTRODUCTION 08 II. LANDSCAPE AND KEY CONSIDERATIONS 13 III. RECOMMENDATIONS 22 IV. PRIMER: DIFFERENT TYPES OF INVESTMENTS IN EARLY-STAGE ENTERPRISES 27 V. CONCLUSION APPENDIX: 28 A. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 29 B. LANDSCAPE OF EQUITABLE MEDIA INVESTORS AND ADJACENT INVESTORS I. -

Anshul Arora, and Sateesh Kumar Peddoju Department of Computer Science and Engineering INDIAN INSTITUTE of TECHNOLOGY ROORKEE

Anshul Arora, and Sateesh Kumar Peddoju Department of Computer Science and Engineering INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ROORKEE List of Normal Apps Considered for Mobile Malware Detection. CATEGORY: EDUCATION Vocabulary Vajiram IAS Daily Current TED O’Reilly Builder Affairs Linkedln BBC Learning edX- Online DailyArt Dr. Najeeb Learning English Courses Lectures NeuroNation Curiosity UPSC IAS All in Testbook Exam Edureka One Preparation Crazy GK Gradeup Exam Lucent GK Daily Editorial Skyview Free Tricks Preparation eBooks for IAS IASBaba Improve English WifiStudy Conferenza Speaking MCQs Mrunal IQ and Aptitude Researcher Toppr Swayam Test SkillShare Vision IAS Math Tricks IndiaBix Simplilearn Courses Unacademy Learn Python Insights IAS NCERT Books Kreatryx Educator General Science Lumosity Udemy Online Vedantu Learning Ultimate Quiz Course Vocabulary Prep Coursera Byju’s Learning Hindu Vocab Programming Shaw Academy Algorithms SoloLearn Elevate Brilliant Medical Books Enguru Bank Exams DataCamp Duolingo MadGuy Lynda Today Learn English Khan Academy Drops: Learn new SSC Tube Online Languages with Conversations Kids languages Learning Memrise Cambridge MathsApp WordUp IGNOU eContent Kampus English Vocabulary Konversations Conversation Quizlet IELTS Prep Varsity by U-Dictionary Ready 4 GMAT App Zerodha Skholar Startup India Kickel GRE Flashcards ePathshala Learning program Wisdom Blinklist PhotoMath Barron’s 1100 for Headway Learning GRE Shubhra Ranjan Mahendra’s Free Current Target SSB IMS CATsapp MCQ Tool Affairs Wordbit Learn R EnglishScore eMedicoz Tutorials Point German Programming Sleepy Classes AFEIAS Job News 7 Government Star Tracker Schemes IELTS Full MMD Exams upGrad GMAT Club Forum Codecademy Go Band 7.5+ Free IIT JEE Mission UPSC Learning Space 3e Learning Edu Tap Anshul Arora, and Sateesh Kumar Peddoju Department of Computer Science and Engineering INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ROORKEE List of Normal Apps Considered for Mobile Malware Detection. -

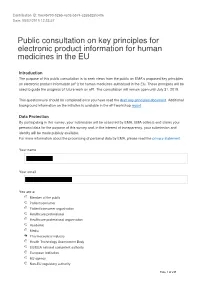

Public Consultation on Key Principles for Electronic Product Information for Human Medicines in the EU

Contribution ID: 0ec45790-026b-4c03-b574-c265d25fc48e Date: 08/07/2019 12:33:57 Public consultation on key principles for electronic product information for human medicines in the EU Introduction The purpose of this public consultation is to seek views from the public on EMA’s proposed key principles on electronic product information (ePI) for human medicines authorised in the EU. These principles will be used to guide the progress of future work on ePI. The consultation will remain open until July 31, 2019. This questionnaire should be completed once you have read the draft key principles document. Additional background information on the initiative is available in the ePI workshop report. Data Protection By participating in this survey, your submission will be assessed by EMA. EMA collects and stores your personal data for the purpose of this survey and, in the interest of transparency, your submission and identity will be made publicly available. For more information about the processing of personal data by EMA, please read the privacy statement. Your name Your email You are a: Member of the public Patient/consumer Patient/consumer organisation Healthcare professional Healthcare professional organisation Academic Media Pharmaceutical industry Health Technology Assessment Body EU/EEA national competent authority European Institution EU agency Non-EU regulatory authority Page 1 of 235 Other Name of your organisation: Synthon BV Indicate the key principle you would like to comment on (select all that apply): 1.1 ePI 1.2 Common EU electronic -

The Bio Revolution: Innovations Transforming and Our Societies, Economies, Lives

The Bio Revolution: Innovations transforming economies, societies, and our lives economies, societies, our and transforming Innovations Revolution: Bio The The Bio Revolution Innovations transforming economies, societies, and our lives May 2020 McKinsey Global Institute Since its founding in 1990, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) has sought to develop a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy. As the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company, MGI aims to help leaders in the commercial, public, and social sectors understand trends and forces shaping the global economy. MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management, employing the analytical tools of economics with the insights of business leaders. Our “micro-to-macro” methodology examines microeconomic industry trends to better understand the broad macroeconomic forces affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports have covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses on six themes: productivity and growth, natural resources, labor markets, the evolution of global financial markets, the economic impact of technology and innovation, and urbanization. Recent reports have assessed the digital economy, the impact of AI and automation on employment, physical climate risk, income inequal ity, the productivity puzzle, the economic benefits of tackling gender inequality, a new era of global competition, Chinese innovation, and digital and financial globalization. MGI is led by three McKinsey & Company senior partners: co-chairs James Manyika and Sven Smit, and director Jonathan Woetzel. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, Anu Madgavkar, Jan Mischke, Sree Ramaswamy, Jaana Remes, Jeongmin Seong, and Tilman Tacke are MGI partners, and Mekala Krishnan is an MGI senior fellow. -

Use Youtube to Grow Your Business Fall 2020

Use YouTube to Grow Your Business #GrowWithGoogle TELL GOOGLE YOUR SUCCESS STORIES! Google is collecting stories from our events about real people like you! We’re creating new advertising and partnerships Email me after today’s presentation [email protected] Give Simple, 1 sentence answers to these questions: 1. Who you are and what you do? 2. What you learned today that was most valuable and how it will help? 3. Have you achieved success using any of Google’s tools or products? Erin Bemis, IOM LinkedIn: Erin Bemis YOUTUBE IS WHERE PEOPLE WATCH YouTube has over 2 billion monthly logged in users. These users watch 1 billion hours of video per day.1 YouTube Internal Data (logged In user = Google user ID accounts that visit YouTube in a 28 day period), Global, April 2018. 4 YOUTUBE IS WHERE PEOPLE DISCOVER 68% of YouTube users watched YouTube to help make a purchase decision. Google/Ipsos Connect, U.S., YouTube Cross Screen Survey, Jul. 2016. 5 YOUTUBE IS WHERE PEOPLE ENGAGE People watch videos. You can use that focused interest to help grow your business with YouTube. 6 CONNECT WITH CUSTOMERS AS THEY WATCH, DISCOVER, AND ENGAGE Watched Visits dealership’s Remarketed on Test drive Bumper ad website YouTube scheduled Watched Google search for Cookie Visit dealership’s Visit dealership YouTube video “Sunnyvale Motors” stored website again And purchase 7 AGENDA CREATE A HOME FOR YOUR BUSINESS ON YOUTUBE CREATE VIDEOS THAT HELP YOU ACHIEVE YOUR BUSINESS GOALS ORGANIZE YOUR CHANNEL TO ATTRACT VIEWERS PROMOTE YOUR BUSINESS WITH VIDEO HOW TO STREAM VIDEO WITH YOUTUBE LIVE RESOURCES Create a home for your business on YouTube 9 CREATE YOUR CHANNEL Sign into YouTube with your Google Account. -

Cloud Computing Industry Primer Market Research Research and Education

August 17, 2020 UW Finance Association Cloud Computing Industry Primer Market Research Research and Education Cloud Computing Industry Primer All amounts in $US unless otherwise stated. Author(s): What is Cloud Computing? Rohit Dabke, Kevin Hsieh and Ethan McTavish According to the National Institution of Standards and Research Analysts Technology (NIST), Cloud Computing is defined as a model for Editor(s): enabling network access to a shared pool of configurable John Derraugh and Brent Huang computing resources that can be rapidly provisioned. In more Co-VPs of Research and Education layman terms, Cloud Computing is the delivery of different computing resources on demand via the Internet. These computing resources include network, servers, storage, applications, and other services which users can ‘rent’ from the service provider at a cost, without having to worry about maintaining the infrastructure. As long as an electronic device has access to the web, it has access to the service provided. In the long run, people and businesses can save on cost and increase productivity, efficiency, and security. • Exhibit 1: See below the advantages and features of cloud computing. In general, cloud computing can be broken down into three major categories of service models: Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), Platform as a Service (PaaS), and Software as a Service (SaaS). Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) IaaS involves the cloud service provider supplying on-demand infrastructure components such as networking, servers, and storage. The customer will be responsible for establishing its own platform and applications but can rely on the provider to maintain the background infrastructure. August 17, 2020 1 UW Finance Association Cloud Computing Industry Primer Major IaaS providers include Microsoft (Microsoft Azure), Amazon (Amazon Web Service), IBM (IBM Cloud), Alibaba Cloud, and Alphabet (Google Cloud). -

Venture Capital and the Finance of Innovation, Second Edition

This page intentionally left blank VENTURE CAPITAL & THE FINANCE OF INNOVATION This page intentionally left blank VENTURE CAPITAL & THE FINANCE OF INNOVATION SECOND EDITION ANDREW METRICK Yale School of Management AYAKO YASUDA Graduate School of Management, UC Davis John Wiley & Sons, Inc. EDITOR Lacey Vitetta PROJECT EDITOR Jennifer Manias SENIOR EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Emily McGee MARKETING MANAGER Diane Mars DESIGNER RDC Publishing Group Sdn Bhd PRODUCTION MANAGER Janis Soo SENIOR PRODUCTION EDITOR Joyce Poh This book was set in Times Roman by MPS Limited and printed and bound by Courier Westford. The cover was printed by Courier Westford. This book is printed on acid free paper. Copyright 2011, 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, website www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, (201)748-6011, fax (201)748-6008, website http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Evaluation copies are provided to qualified academics and professionals for review purposes only, for use in their courses during the next academic year. These copies are licensed and may not be sold or transferred to a third party. -

Digital Skills for Everyday Tasks

Digital Skills for Everyday Tasks google.com/grow #GrowWithGoogle WORKING REMOTELY ● Keep your routine. ● Create a dedicated work “spot” and customize it. ● Schedule lunch and breaks. ● Make sure you have the tools you need. ● Create a daily to-do list, the day before. ● Give your co-workers grace. ● If you’re not “at work,” don’t work. 2 EVERYDAY TASKS FOR REMOTE WORK ● Keep track of your to-do lists. ● Collaborate with your team in virtual documents. ● Share your progress often. 3 AGENDA SIGN IN TO YOUR GOOGLE ACCOUNT ACCESS GOOGLE DRIVE MAKE A TO-DO LIST IN GOOGLE SHEETS CREATE A MEETING AGENDA IN GOOGLE DOCS BUILD A STATUS UPDATE PRESENTATION IN GOOGLE SLIDES 4 STEP 1: SIGN IN TO YOUR GOOGLE ACCOUNT Sign in to your Google Account. Quick Tip: Don’t have a Google Account? Take a moment to create one now! google.com 5 GOOGLE APPLICATIONS Google Applications Sheets Gmail Docs Chrome Slides Photos 6 STEP 2: ACCESS GOOGLE DRIVE Click Google Apps. Click Google Drive to access a file. Quick Tip: You can also click one of the Google Apps to start a new file. sheets.google.com 7 Create a to-do list with Google Sheets 8 STEP 3: ACCESS GOOGLE SHEETS Click New. Click Google Sheets. Click From a template. Click To-do list. 9 STEP 4: POPULATE YOUR SHEET Add tasks. Add dates. 10 STEP 4: POPULATE YOUR SHEET Add tasks. Add dates. 11 STEP 5: ADD COLUMNS AND POPULATE ROWS Add columns. Populate rows. 12 STEP 6: FORMAT YOUR SHEET Change the fill color. -

Google Design Thinking for Entrepreneurs

Design Thinking for Entrepreneurs google.com/grow #GrowWithGoogle LET’S GET ACQUAINTED Roberto Martinez Google Digital Coach - LA Grow with Google Digital Coach www.grow.google/digitalcoaches [email protected] @robthemarketer @robertombraven linkedin.com/in/robthemarketer AGENDA WHAT IS DESIGN THINKING? Learn the five phases of the Design Thinking process UNDERSTAND YOUR AUDIENCE Define who your audience is and what makes them tick IDENTIFY THEIR CHALLENGES Understand how to empathize with your potential customers CRAFT AND TEST YOUR SOLUTIONS Brainstorm how you can solve the problems of your audience 3 SIGN IN TO YOUR GOOGLE ACCOUNT 1 Sign in to your Google Account. Don’t have a Google Account? No problem! We’ve got Test Accounts. For a closer look: See Page 2 of the Follow Along Guide 4 ACCESS GOOGLE DRIVE AND GOOGLE DOCS Click Google Apps. Click Google Drive to access a file. OR Click one of the Google Apps to start a new file. For a closer look: See Page 3 of the Follow Along Guide 5 ACCESS GOOGLE DOCS Click New. Click Google Docs. Click Blank document For a closer look: See Page 4 of the Follow Along Guide 6 What is Design Thinking? Design thinking is a creative problem-solving process that focuses on a user-centered approach to create a solution that is technologically and economically feasible. 7 THE PROCESS 1 2 3 4 5 Empathize Define Ideate Prototype Test Observe, Express the Identify Get ideas out Test, learn, engage, and problem in the problems to and into the iterate, and immerse form of POVs find solutions world repeat For a closer look: See Page 5 of the Follow Along Guide 8 DESIGN THINKING IN OUR EVERYDAY LIVES On demand Foot activated Ride and home television sharing car door 9 Define Empathize Ideate Prototype Test Empathize Grow with Google #growwithgoogle Define Empathize Ideate Prototype Test ESTABLISHING EMPATHY Your goal Connect to the user’s story, emotions, and your insights about them. -

Gestão 4.0 Em Tempos De Disrupção

GARCIA Solimar Garcia organizadora GESTÃO 4.0 fe fe NA BUSCA DAS PERGUNTAS CERTAS Gestão 4.0 em tempos de disrupção GESTÃO 4.0 EM TEMPOS DE DISRUPÇÃO DE TEMPOS EM 4.0 GESTÃO EM TEMPOS DE DISRUPÇÃO A busca de respostas para diversas perguntas ligadas a temas complexos que Para responder perguntas cruciais sobre a compõem esse livro Gestão 4.0 em tempos de disrupção foi uma proposição Gestão 4.0 foram abordadas nesse livro áre- ousada, atual e inédita, cuja espinha dorsal é a Gestão 4.0, envolvida pelas as diversas sobre as quais você vai encontrar tecnologias que transformam o mundo e quebram paradigmas em todas as áreas. discussão e atualização, incluindo tecnologias da informação, futuro do trabalho, economia fe Numa atualidade que é volátil, incerta, complexa e ambígua (VUCA) assistimos à ascensão da Quarta Revolução Industrial, com acentuada valorização do mercado circular, educação e educação a distância, Profa. Dra. Solimar Garcia de consumo e um avanço tecnológico sem precedentes. É a Indústria 4.0, trazendo treinamento e desenvolvimento, atendimento organizadora disrupção e mudanças rápidas, constantes e urgentes à área de Gestão, aqui a clientes, marketing digital e área comercial, agronegócio, inteligência empresarial, segu- Escritora com diversos livros publicados, tratada por Gestão 4.0, com a tecnologia como fator preponderante. rança do trabalho, comércio global, saúde e pesquisadora e jornalista com mais de 30 O Prof. José Salibi Neto, em um prefácio instigante, apresenta os assuntos gestão hospitalar. anos de experiência profissional, passou tratados como audaciosos, e comenta que, além das respostas, a busca por Adriana Pavarina por diversos órgãos de imprensa e revis- Na transformação advinda da Quarta Revolução perguntas colabora com a discussão necessária para aclarar a Gestão 4.0 e ser um Angeles Treitero García Cônsolo tas especializadas, além de empresas na Industrial, as novidades se transformam em ino- apoio às lideranças empresariais, de forma prática aliada à pesquisa acadêmica. -

Rebound? Invest Your Time Wisely and Digitize Your Travel Business

Contents Respond: How can Google My Business help right now? A guide on what you can do now as a travel business owner Prepare: What can you do now to prepare for rebound? Invest your time wisely and digitize your travel business Rebound: Life post circuit breaker - how to rebound? Guidelines on what you can do to rebound with Google My Business Proprietary + Confidential Respond How can Google My Business help right now? For the most recent updates on how Google My Business can help during the COVID-19 situation, please make sure to visit the below pages. Google: “Google help center guidance for businesses affected by COVID-19” Note that businesses may see delays in getting new verifications processed due to current situation. Google: “Limited Google My Business functionality due to COVID-19” Proprietary + Confidential Proprietary + Confidential Stay up to date on GMB For the latest updates and GMB features in your area, check the COVID-19 dashboard card on your account page. From here, you can learn more about the features we’ve just covered. Dashboard Card Proprietary + Confidential Proprietary + Confidential Is your business visible on Google Maps & Google Search? Google My Business lets you engage with customers in the moments that matter with a Business Profile that shows who you are, what you do, and what you have to offer on Google Maps and Google Search on phone, desktop, laptop & tablet. Proprietary + Confidential Proprietary + Confidential If not: Create a Business Profile with Google My Business STEP 1: SIGN INTO YOUR GOOGLE ACCOUNT Sign into the Google Account you use for your business.