Aging and Old Age in TV Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sean Callery

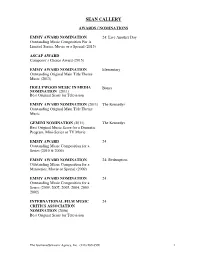

SEAN CALLERY AWARDS / NOMINATIONS EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24: Live Another Day Outstanding Music Composition For A Limited Series, Movie or a Special (2015) ASCAP AWARD Composer’s Choice Award (2015) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION Elementary Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music (2013) HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA Bones NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score for Television EMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2011) The Kennedys Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music GEMINI NOMINATION (2011) The Kennedys Best Original Music Score for a Dramatic Program, Mini-Series or TV Movie EMMY AWARD 24 Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (2010 & 2006) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24: Redemption Outstanding Music Composition for a Miniseries, Movie or Special (2009) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24 Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (2009, 2007, 2005, 2004, 2003, 2002) INTERNATIONAL FILM MUSIC 24 CRITICS ASSOCIATION NOMINATION (2006) Best Original Score for Television The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 SEAN CALLERY TELEVISION SERIES JESSICA JONES (series) Melissa Rosenberg, Jeph Loeb, exec. prods. ABC / Marvel Entertainment / Tall Girls Melissa Rosenberg, showrunner BONES (series) Barry Josephson, Hart Hanson, Stephen Nathan, Fox / 20 th Century Fox Steve Bees, exec. prods. HOMELAND (pilot & series) Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Avi Nir, Gideon Showtime / Fox 21 Raff, Ran Telem, exec. prods. ELEMENTARY (pilot & series) Carl Beverly, Robert Doherty, Sarah Timberman, CBS / Timberman / Beverly Studios Craig Sweeny, exec. prods. MINORITY REPORT (pilot & series) Kevin Falls, Max Borenstein, Darryl Frank, 20 th Century Fox Television / Fox Justin Falvey, exec. prods. Kevin Falls, showrunner MEDIUM (series) Glenn Gordon Caron, Rene Echevarria, Kelsey Paramount TV /CBS Grammer, Ronald Schwary, exec. prods. 24: LIVE ANOTHER DAY (event-series) Kiefer Sutherland, Howard Gordon, Brian 20 TH Century Fox Grazer, Jon Cassar, Evan Katz, Robert Cochran, David Fury, exec. -

Representations and Discourse of Torture in Post 9/11 Television: an Ideological Critique of 24 and Battlestar Galactica

REPRESENTATIONS AND DISCOURSE OF TORTURE IN POST 9/11 TELEVISION: AN IDEOLOGICAL CRITIQUE OF 24 AND BATTLSTAR GALACTICA Michael J. Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2008 Committee: Jeffrey Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin ii ABSTRACT Jeffrey Brown Advisor Through their representations of torture, 24 and Battlestar Galactica build on a wider political discourse. Although 24 began production on its first season several months before the terrorist attacks, the show has become a contested space where opinions about the war on terror and related political and military adventures are played out. The producers of Battlestar Galactica similarly use the space of television to raise questions and problematize issues of war. Together, these two television shows reference a long history of discussion of what role torture should play not just in times of war but also in a liberal democracy. This project seeks to understand the multiple ways that ideological discourses have played themselves out through representations of torture in these television programs. This project begins with a critique of the popular discourse of torture as it portrayed in the popular news media. Using an ideological critique and theories of televisual realism, I argue that complex representations of torture work to both challenge and reify dominant and hegemonic ideas about what torture is and what it does. This project also leverages post-structural analysis and critical gender theory as a way of understanding exactly what ideological messages the programs’ producers are trying to articulate. -

Gossip, Exclusion, Competition, and Spite: a Look Below the Glass Ceiling at Female-To-Female Communication Habits in the Workplace

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2013 Gossip, Exclusion, Competition, and Spite: A Look Below the Glass Ceiling at Female-to-Female Communication Habits in the Workplace Katelyn Elizabeth Brownlee [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Organizational Communication Commons Recommended Citation Brownlee, Katelyn Elizabeth, "Gossip, Exclusion, Competition, and Spite: A Look Below the Glass Ceiling at Female-to-Female Communication Habits in the Workplace. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1597 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Katelyn Elizabeth Brownlee entitled "Gossip, Exclusion, Competition, and Spite: A Look Below the Glass Ceiling at Female-to-Female Communication Habits in the Workplace." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Michelle Violanti, Major Professor We have read this thesis -

Netflix Adds to Original Shows with Sony Deal 15 October 2013

Netflix adds to original shows with Sony deal 15 October 2013 programming to make itself a preferred location for on-demand streaming. "We were spellbound after hearing Todd, Glenn and Daniel's pitch, and knew Netflix was the perfect home for this suspenseful family drama that is going to have viewers on the edge of their seats," said Netflix vice president of original content Cindy Holland. Netflix scored a recent hit with its political drama "House of Cards," tossing conventional TV wisdom out the window when it released a full season in one fell swoop early this year. The Netflix company logo is seen at Netflix headquarters The series, which was nominated for a 2013 Emmy in Los Gatos, CA on Wednesday, April 13, 2011 for best drama, joins a recent spate of original Netflix programming that includes new episodes of "Arrested Development," plus the series "Orange is the New Black" and "Hemlock Grove." Netflix on Monday announced a deal with Sony to create a psychological thriller series for the online Netflix sees original programming as part of a streaming and DVD service, ramping up original formula to gain and hold subscribers at its $7.99-a- programming to win subscribers. month fee that covers a vast catalog of pre- released TV shows and movies. "Damages" creators Todd Kessler, Daniel Zelman, and Glenn Kessler will begin production of a © 2013 AFP 13-episode first season of the show from Sony Pictures Television early next year. The yet-unnamed series will broadcast exclusively on Netflix, according to the California-based Internet company. -

Desperate Housewives a Lot Goes on in the Strange Neighborhood of Wisteria Lane

Desperate Housewives A lot goes on in the strange neighborhood of Wisteria Lane. Sneak into the lives of five women: Susan, a single mother; Lynette, a woman desperately trying to b alance family and career; Gabrielle, an exmodel who has everything but a good m arriage; Bree, a perfect housewife with an imperfect relationship and Edie Britt , a real estate agent with a rocking love life. These are the famous five of Des perate Housewives, a primetime TV show. Get an insight into these popular charac ters with these Desperate Housewives quotes. Susan Yeah, well, my heart wants to hurt you, but I'm able to control myself! How would you feel if I used your child support payments for plastic surgery? Every time we went out for pizza you could have said, "Hey, I once killed a man. " Okay, yes I am closer to your father than I have been in the past, the bitter ha tred has now settled to a respectful disgust. Lynette Please hear me out this is important. Today I have a chance to join the human rac e for a few hours there are actual adults waiting for me with margaritas. Loo k, I'm in a dress, I have makeup on. We didn't exactly forget. It's just usually when the hostess dies, the party is off. And I love you because you find ways to compliment me when you could just say, " I told you so." Gabrielle I want a sexy little convertible! And I want to buy one, right now! Why are all rich men such jerks? The way I see it is that good friends support each other after something bad has happened, great friends act as if nothing has happened. -

The Rise of the Anti-Hero: Pushing Network Boundaries in the Contemporary U.S

The Rise of The Anti-Hero: Pushing Network Boundaries in The Contemporary U.S. Television YİĞİT TOKGÖZ Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in CINEMA AND TELEVISION KADIR HAS UNIVERSITY June, 2016 I II ABSTRACT THE RISE OF THE ANTI-HERO: PUSHING NETWORK BOUNDARIES IN THE CONTEMPORARY U.S. TELEVISION Yiğit Tokgöz Master of Arts in Cinema and Television Advisor: Dr. Elif Akçalı June, 2016 The proliferation of networks using narrowcasting for their original drama serials in the United States proved that protagonist types different from conventional heroes can appeal to their target audiences. While this success of anti-hero narratives in television serials starting from late 1990s raises the question of “quality television”, developing audience measurement models of networks make alternative narratives based on anti-heroes become widespread on the U.S. television industry. This thesis examines the development of the anti-hero on the U.S. television by focusing on the protagonists of pay-cable serials The Sopranos (1999-2007) and Dexter (2006-2013), basic cable serials The Shield (2002-2008) and Mad Men (2007-2015), and video-on-demand serials House of Cards (2013- ) and Hand of God (2014- ). In brief, this thesis argues that the use of anti-hero narratives in television is directly related to the narrowcasting strategy of networks and their target audience groups, shaping a template for growing networks and newly formed distribution services to enhance the brand of their corporations. In return, the anti-hero narratives push the boundaries of conventional hero in television with the protagonists becoming morally less tolerable and more complex, introducing diversity to television serials and paving the way even for mainstream broadcast networks to develop serials based on such protagonists. -

Preemptive Narratives in Recent Television Series Par Toni Pape

Université de Montréal Figures of Time: Preemptive Narratives in Recent Television Series par Toni Pape Département de littérature comparée, Faculté des arts et des sciences Thèse présentée à la Faculté des arts et des sciences en vue de l’obtention du grade de Ph. D. en Littérature, option Études littéraires et intermédiales Juillet 2013 © Toni Pape, 2013 Résumé Cette thèse de doctorat propose une analyse des temporalités narratives dans les séries télévisées récentes Life on Mars (BBC, 2006-2007), Flashforward (ABC, 2009-2010) et Damages (FX/Audience Network, 2007-2012). L’argument général part de la supposition que les nouvelles technologies télévisuelles ont rendu possible de nouveaux standards esthétiques ainsi que des expériences temporelles originales. Il sera montré par la suite que ces nouvelles qualités esthétiques et expérientielles de la fiction télévisuelle relèvent d’une nouvelle pertinence politique et éthique du temps. Cet argument sera déployé en quatre étapes. La thèse se penche d’abord sur ce que j’appelle les technics de la télévision, c’est-à- dire le complexe de technologies et de techniques, afin d’élaborer comment cet ensemble a pu activer de nouveaux modes d’expérimenter la télévision. Suivant la philosophie de Gilles Deleuze et de Félix Guattari ainsi que les théories des médias de Matthew Fuller, Thomas Lamarre et Jussi Parikka, ce complexe sera conçu comme une machine abstraite que j’appelle la machine sérielle. Ensuite, l’argument puise dans des théories de la perception et des approches non figuratives de l’art afin de mieux cerner les nouvelles qualités d’expérience esthétique dans la fiction sérielle télévisée. -

Nomination Press Release

Brian Boyle, Supervising Producer Outstanding Voice-Over Nahnatchka Khan, Supervising Producer Performance Kara Vallow, Producer American Masters • Jerome Robbins: Diana Ritchey, Animation Producer Something To Dance About • PBS • Caleb Meurer, Director Thirteen/WNET American Masters Ron Hughart, Supervising Director Ron Rifkin as Narrator Anthony Lioi, Supervising Director Family Guy • I Dream of Jesus • FOX • Fox Mike Mayfield, Assistant Director/Timer Television Animation Seth MacFarlane as Peter Griffin Robot Chicken • Robot Chicken: Star Wars Episode II • Cartoon Network • Robot Chicken • Robot Chicken: Star Wars ShadowMachine Episode II • Cartoon Network • Seth Green, Executive Producer/Written ShadowMachine by/Directed by Seth Green as Robot Chicken Nerd, Bob Matthew Senreich, Executive Producer/Written by Goldstein, Ponda Baba, Anakin Skywalker, Keith Crofford, Executive Producer Imperial Officer Mike Lazzo, Executive Producer The Simpsons • Eeny Teeny Maya, Moe • Alex Bulkley, Producer FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Corey Campodonico, Producer Century Fox Television Hank Azaria as Moe Syzlak Ollie Green, Producer Douglas Goldstein, Head Writer The Simpsons • The Burns And The Bees • Tom Root, Head Writer FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Hugh Davidson, Written by Century Fox Television Harry Shearer as Mr. Burns, Smithers, Kent Mike Fasolo, Written by Brockman, Lenny Breckin Meyer, Written by Dan Milano, Written by The Simpsons • Father Knows Worst • FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Kevin Shinick, -

Rose Byrne Under Wraps How She Charmed the World with Her Hidden Talent

JULY 31, 2016 + TALL ORDER: DOES YOUR DATE MEASURE UP? SHIFT YOUR CAREER UP A GEAR DECADENT PEANUT BUTTER DESSERTS ROSE BYRNE UNDER WRAPS HOW SHE CHARMED THE WORLD WITH HER HIDDEN TALENT SNS31JUL16p001 1 22/07/16 3:27 PM (cover_story) Roses She’s no garden-variety star. Rose Byrne is now in full bloom as a sought-after comic actor, says Tiffany Bakker 10 | SUNDAYSTYLE.COM.AU 11 SVS31JUL16p010 10 22/07/16 4:48 PM ose Byrne is pondering like I’m a big name,” she says. “I feel like her day job. “Acting is I’ve been very lucky in the people I’ve embarrassing, absolutely,” been able to work with.” she says, with a hearty laugh. In recent years, of course, there has R“Just the vulnerability it requires, whether been her much-vaunted emergence as in a performance or doing interviews. It’s a big-screen comedy superstar (more an odd thing, and it’s also a bit of a silly job. on that later), but she has just as easily I mean, it’s a great job, and I take it navigated indie drama (Adult Beginners), seriously and I’m passionate about it, but dramedy (The Meddler), horror (Insidious), I know I’m not curing cancer, so you have musicals (Annie), tent-pole franchises (the to have some perspective on it.” X-Men series), and television (Damages). When we meet, Byrne is mid-pedicure Ask her to reflect on her extraordinary at a downtown New York hotel, apologising success and she squirms slightly. -

Desperate Housewives

Desperate Housewives Titre original Desperate Housewives Autres titres francophones Beautés désespérées Genre Comédie dramatique Créateur(s) Marc Cherry Musique Steve Jablonsky, Danny Elfman (2 épisodes) Pays d’origine États-Unis Chaîne d’origine ABC Nombre de saisons 5 Nombre d’épisodes 108 Durée 42 minutes Diffusion d’origine 3 octobre 2004 – en production (arrêt prévu en 2013)1 Desperate Housewives ou Beautés désespérées2 (Desperate Housewives en version originale) est un feuilleton télévisé américain créé par Charles Pratt Jr. et Marc Cherry et diffusé depuis le 3 octobre 2004 sur le réseau ABC. En Europe, le feuilleton est diffusé depuis le 8 septembre 2005 sur Canal+ (France), le 19 mai sur TSR1 (Suisse) et le 23 mai 2006 sur M6. En Belgique, la première saison a été diffusée à partir de novembre 2005 sur RTL-TVI puis BeTV a repris la série en proposant les épisodes inédits en avant-première (et avec quelques mois d'avance sur RTL-TVI saison 2, premier épisode le 12 novembre 2006). Depuis, les diffusions se suivent sur chaque chaîne francophone, (cf chaque saison pour voir les différentes diffusions : Liste des épisodes de Desperate Housewives). 1 Desperate Housewives jusqu'en 2013 ! 2La traduction littérale aurait pu être Ménagères désespérées ou littéralement Épouses au foyer désespérées. Synopsis Ce feuilleton met en scène le quotidien mouvementé de plusieurs femmes (parfois gagnées par le bovarysme). Susan Mayer, Lynette Scavo, Bree Van De Kamp, Gabrielle Solis, Edie Britt et depuis la Saison 4, Katherine Mayfair vivent dans la même ville Fairview, dans la rue Wisteria Lane. À travers le nom de cette ville se dégage le stéréotype parfaitement reconnaissable des banlieues proprettes des grandes villes américaines (celles des quartiers résidentiels des wasp ou de la middle class). -

Lehigh Preserve Institutional Repository

Lehigh Preserve Institutional Repository Embracing Islam in the Age of Terror: Post 9/11 Representations of Islam and Muslims in the United States and Personal Stories of American Converts Brunet, Clemence 2013 Find more at https://preserve.lib.lehigh.edu/ This document is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Embracing Islam in the Age of Terror: Post 9/11 Representations of Islam and Muslims in the United States and Personal Stories of American Converts by Clemence Brunet A Thesis Presented to the Graduate and Research Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in American Studies Lehigh University May 2013 i © 2013 Copyright Clemence Brunet ii Thesis is accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in American Studies. Embracing Islam in the Age of Terror: Post 9/11 Representations of Islam and Muslims in the United States and Personal Stories of American Converts Clemence Brunet Date Approved Thesis Director Dr. Saladin Ambar Co-Director Dr. Bruce Whitehouse Department Chair Dr. Edward Whitley iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Chapter One: Perceptions and Representations of Islam and Muslims after 9/11: language, media, hate groups and public opinion 8 Chapter Two: Muslim terrorists in the Entertainment Media and American Jihadists in the Media 49 Chapter Three: Personal Stories and Experiences of White American converts to Islam 85 Conclusion 133 Works Cited 138 Vita 155 iv ABSTRACT The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 were one of the most traumatic events experienced by the American people on their soil. -

Television Drama Series' Incorporation of Film

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Universidade do Minho: RepositoriUM Zagalo, N., Barker, A., (2006), Television Drama Series’ Incorporation of Film Narrative Innovation: 24, In Anthony Barker (ed.), Television, Aesthetics and Reality, Cambridge Scholars Press, ISBN 1-84718-008-6 TELEVISION DRAMA SERIES ’ INCORPORATION OF FILM NARRATIVE INNOVATION : THE CASE OF 24 Nelson Zagalo and Anthony Barker 1. The Golden Age Joyard (2003) refers to the past decade as the Golden Age of the American series, mostly in connection with their narrative features and their capacity to arouse emotions. 24 (2001) by Joel Surnow and Robert Cochran illustrates perfectly these innovative capacities in dramatic series. The series concept is everything, making 24 an instant cult object. It is presented as the nearest to real time that any artistic work can achieve. The continuous flow of events from 24 enters our homes through our TV sets permitting us to follow an apparent reality, projected week by week at the same hour, but making us feel a contemporaneous experience from a use of a space/time that struggles against illusion. Creative liberty has permitted the development of new narrative trends (Thompson, 2003), just as unusual aesthetic forms new to television (Nelson, 2001) have striven to deliver greater degrees of realism. Narrative complexity is increasing, becoming more intricate not only at the plot level but also at the level of character development, which might lead us to believe that television series are positioning themselves in the vanguard of visual media narrative. Surnow in interview (Cohen and Joyard, 2003) refers to this television as a new land of opportunity for creative and original artworks, based upon a freedom promoted by cable television (and here we should mention the impressive achievement of the pay cable channel Home Box Office in backing ground-breaking new TV series) which allows artists to transcend the constraints of Hollywood dictated by economic globalization.