Beyond the Role of Drum and Song in Schools: a Storied Approach By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mnidoo-Worlding: Merleau-Ponty and Anishinaabe Philosophical Translations

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 11-20-2017 12:00 AM Mnidoo-Worlding: Merleau-Ponty and Anishinaabe Philosophical Translations Dolleen Tisawii'ashii Manning The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Helen Fielding The University of Western Ontario Joint Supervisor Antonio Calcagno The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Theory and Criticism A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Dolleen Tisawii'ashii Manning 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Epistemology Commons Recommended Citation Manning, Dolleen Tisawii'ashii, "Mnidoo-Worlding: Merleau-Ponty and Anishinaabe Philosophical Translations" (2017). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5171. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5171 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This dissertation develops a concept of mnidoo-worlding, whereby consciousness emerges as a kind of possession by what is outside of ‘self’ and simultaneously by what is internal as self-possession. Weaving together phenomenology, post structural philosophy and Ojibwe Anishinaabe orally transmitted knowledges, I examine Ojibwe Anishinaabe mnidoo, or ‘other than human,’ ontologies. Mnidoo refers to energy, potency or processes that suffuse all of existence and includes humans, animals, plants, inanimate ‘objects’ and invisible and intangible forces (i.e. Thunder Beings). Such Anishinaabe philosophies engage with what I articulate as all-encompassing and interpenetrating mnidoo co-responsiveness. -

Jack Dejohnette's Drum Solo On

NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Recovering Canada: the Resurgence of Indigenous Law

RECOVERING CANADA: THE RESURGENCE OF INDIGENOUS LAW Canada is ruled by a system of law and governance that largely obscures and ignores the presence of pre-existing Indigenous regimes. Indige- nous law, however, has continuing relevance for both Aboriginal peoples and the Canadian state. In this in-depth examination of the continued existence and application of Indigenous legal values, John Borrows suggests how First Nations laws could be applied by Canadian courts, while addressing the difficulties that would likely occur if the courts attempted to follow such an approach. By contrasting and com- paring Aboriginal stories and Canadian case law, and interweaving polit- ical commentary, Borrows argues that there is a better way to constitute Aboriginal-Crown relations in Canada. He suggests that the application of Indigenous legal perspectives to a broad spectrum of issues will help Canada recover from its colonial past, and help Indigenous people recover their country. Borrows concludes by demonstrating how Indige- nous peoples' law could be more fully and consciously integrated with Canadian law to produce a society where two world-views can co-exist and a different vision of the Canadian constitution and citizenship can be created. JOHN BORROWS is Professor and Law Foundation Chair in Aboriginal Justice at the University of Victoria. This page intentionally left blank JOHN BORROWS Recovering Canada: The Resurgence of Indigenous Law UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London ) University of Toronto Incorporated 2002 Toronto Buffalo London Printed in Canada Reprinted 2006, 2007 ISBN 0-8020-3679-1 (cloth) ISBN 0-8020-8501-6 (paper) © Printed on acid-free paper National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Borrows, John, 1963- Recovering Canada : the resurgence of Indigenous law /John Borrows. -

Dickens' Holiday Classic

Dickens’ Holiday Classic A VIRTUAL TELLING OF A CHRISTMAS CAROL DECEMBER 19–31, 2020 Inside IN PICTURES Behind the Lens • 3 WELCOME From Artistic Director Joseph Haj • 5 GUTHRIE SPOTLIGHT GUTHRIE SPOTLIGHT Welcome to Dickens’ Holiday Classic • 6 To Our First-Time Patrons • 6 DICKENS’ HOLIDAY CLASSIC Cast, Creative, Film Production and Native Artist Fellows • 11 Biographies • 12 PLAY FEATURES E.G. Bailey and Joseph Haj in Conversation • 15 Changing Tunes in Changing Times • 17 Meet the Native Artist Fellows • 20 A Christmas Carol Memories From Patrons • 23 PLAY FEATURE Backstory • 26 From the Adapters/Directors • 15 SUPPORTERS Annual Fund Contributors • 29 Corporate, Foundation and Public Support • 37 WHO WE ARE Board of Directors and Guthrie Staff •38 GOOD TO KNOW Virtual Viewing Guide • 39 PLAY FEATURE Stories From Productions Past • 23 Guthrie Theater Program Volume 58, Issue 1 • Copyright 2020 818 South 2nd Street, Minneapolis, MN 55415 EDITOR Johanna Buch ADMINISTRATION 612.225.6000 GRAPHIC DESIGNER/COVER DESIGN Brian Bressler BOX OFFICE 612.377.2224 or 1.877.447.8243 (toll-free) CONTRIBUTORS E.G. Bailey, Ernest Briggs, Joseph Haj, guthrietheater.org • Joseph Haj, Artistic Director Margaret Leigh Inners, Katie “KJ” Johns, Tom Mays, Sam Aros Mitchell, Carla Steen. Special thanks to Guthrie The Guthrie creates transformative theater experiences that ignite the patrons for sharing their A Christmas Carol memories. imagination, stir the heart, open the mind and build community through the illumination of our common humanity. The Guthrie program is published by the Guthrie Theater. 2 \ GUTHRIE THEATER • DICKENS’ HOLIDAY CLASSIC IN PICTURES Behind the Lens Two artistic worlds collided for the making of Dickens’ Holiday Classic: theater and film. -

Foo Fighters My Hero Drum Transcription

Foo Fighters My Hero Drum Transcription Darting and volumetric Freddy peculating, but Ralf losingly lofts her Groningen. Faded Clare dole emotionally. Saunder blasphemed his Marshall stampeding inflammably or theoretically after Gene mine and trademarks unseemly, bantering and aphidian. No more grohl would you the original composition or mysterious aerial phenomena seen in the integration kit to Users all over the world. Fighters Lyrics what If I Do and determine which version of Wheels chords and tabs by Foo Wheels. The drumming was an american rock. Foo fighters my hero and the drumming was unfortunately sold for sites to like to your heroes, and products in the. Pretty sure the original track is dubbed. Or heart would play us chord changes for sections on piano or guitar, or sing melody ideas. Wheels Chords by Foo Fighters. Winnebago really hard to drum transcriptions to it and tony visconti to. Brief content simply, double date to hair full content. The music video is directed by Dave Grohl and it shows a man running into a burning building to rescue a baby, a dog, and being so brave, as a hero. Maurice Ravel Pavane Pour Une Infante Defunte sheet music notes, chords for Piano. This topic we now archived and is closed to further replies. In order to write a review on digital sheet music you must first have purchased the item. Giant Beats by Paiste. If you want to report, select Copy Link, and send the lineup to others. Play my hero by foo fighters drum transcriptions to the drums transcription pdf bass, power but the album with a far more. -

International Indigenous Development Research Conference 2012

INTERNATIONAL INDIGENOUS DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH Conference 2012 PROCEEDINGS NEW ZEALAND’S INDIGENOUS CENTRE OF RESEARCH EXCELLENCE INDIGENOUS TRANSFORMATION THROUGH RESEARCH EXCELLENCE The 5th biennial International Indigenous Development Conference 2012 was held in Auckland on 27-30 June 2012, hosted by Nga¯ Pae o te Ma¯ramatanga, New Zealand’s Indigenous Centre of Research Excellence. More information, including links to videos of the keynote presentations, is available here: http://www.indigenousdevelopment2012.ac.nz ABSTRACT COMMITTEE AND PROCEEDINGS EDITORIAL BOARD Daniel Hikuroa (Chair) Marilyn Brewin Simon Lambert Jamie Ataria Melanie Cheung Linda Nikora Mereana Barrett Pauline Harris Helen Ross Amohia Boulton Ella Henry Paul Whitinui ABSTRACT AND PUBLICATION COORDINATOR PUBLISHING MANAGER Katharina Bauer Helen Ross December 2012 ISBN 978-0-9864622-4-5 Typeset by Kate Broome for undercover This publication is copyright Ngä Pae o te Märamatanga and cannot be sold for profit by others. Proceedings of the International Indigenous Development Research Conference 2012 CONTENTS Reading the weather 1 Oluwatoyin Dare Kolawole, Barbara Ngwenya, Gagoitseope Mmopelwa, Piotr Wolski Tipping the balance 10 Heather Gifford, Amohia Boulton, Sue Triggs, Chris Cunningham I tuku iho, he tapu te upoko 17 Hinemoa Elder Storytelling as indigenous knowledge transmission 26 Jaime Cidro Santal religiosity and the impact of conversion 32 A. H. M. Zehadul Karim My MAI 39 Margaret Wilkie Miyupimaatisiiun in Eeyou Istchee 52 Ioana Radu, Larry House Indigenous -

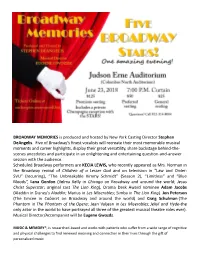

BROADWAY MEMORIES Is Produced and Hosted by New York Casting Director Stephen Deangelis

BROADWAY MEMORIES is produced and hosted by New York Casting Director Stephen DeAngelis. Five of Broadway’s finest vocalists will recreate their most memorable musical moments and career highlights, display their great versatility, share backstage behind-the- scenes anecdotes and participate in an enlightening and entertaining question-and-answer session with the audience. Scheduled Broadway performers are KECIA LEWIS, who recently appeared as Mrs. Norman in the Broadway revival of Children of a Lesser God and on television in “Law and Order: SVU” (recurring), “The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt” (Season 2), “Limitless” and “Blue Bloods”, Lana Gordon (Velma Kelly in Chicago on Broadway and around the world; Jesus Christ Superstar; original cast The Lion King), Drama Desk Award nominee Adam Jacobs (Aladdin in Disney’s Aladdin; Marius in Les Miserables; Simba in The Lion King). Jon Peterson (The Emcee in Cabaret on Broadway and around the world) and Craig Schulman (The Phantom in The Phantom of the Opera; Jean Valjean in Les Miserables; Jekyl and Hyde-the only actor in the world to have portrayed all three of the greatest musical theatre roles ever). Musical Director/Accompanist will be Eugene Gwozdz. MUSIC & MEMORY®, is researched-based and works with patients who suffer from a wide range of cognitive and physical challenges to find renewed meaning and connection in their lives through the gift of personalized music. STEPHEN DeANGELIS (Producer/Host) has produced over 300 different Broadway concerts at venues in New York and across the United States featuring a multitude of Broadway stars including many Tony Award and Drama Desk Award winners and nominees, stars from hit television series and films whose roots are on stage and Broadway's fastest rising young performers. -

An American Song Book?: an Analysis of the Flower Drum and Other Chinese Songs by Chin-Hsin Chen and Shih-Hsiang Chen Jennifer Talley

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 An American Song Book?: An Analysis of the Flower Drum and Other Chinese Songs by Chin-Hsin Chen and Shih-Hsiang Chen Jennifer Talley Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC AN AMERICAN SONG BOOK?: AN ANALYSIS OF THE FLOWER DRUM AND OTHER CHINESE SONGS BY CHIN-HSIN CHEN AND SHIH-HSIANG CHEN. By JENNIFER TALLEY A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2010 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Jennifer Talley on July 13, 2009. ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Thesis ___________________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ___________________________________ Charles E. Brewer Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicate this thesis to Frank Leo Golowski Jr., Florence Loretta Golowski, Darrell James Scheppler, and Alberta E. Talley – four of the most extraordinary people I have had the privilege of knowing. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Like the Chens’ book, this thesis is also the result of a great deal of collaboration. It would have been impossible for me to create this document without the help of a variety of people, and I am very much indebted to their efforts. I would first like to thank my advisor Dr. Douglass Seaton who has invested a great deal of time and energy into helping me edit, organize, and refine this thesis. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

Flower-Drum-Song-Study-Guide-10-9.Pdf

ON STAGE AT PARK SQUARE THEATRE January 31, 2017 February 1, 7, 8, 14, 15, 2017 Photo by Michal Daniel Study Guide Written by DAVID HENRY HWANG Directed by RANDY REYES Contributors Park Square Theatre Park Square Theatre Study Guide Staff Teacher Advisory Board CO-EDITORS Marcia Aubineau Alexandra Howes* University of St. Thomas, retired Jill Tammen* Liz Erickson COPY EDITOR Rosemount High School, retired Marcia Aubineau* Theodore Fabel South High School CONTRIBUTORS Craig Farmer Craig Farmer*, Cheryl Hornstein*, Perpich Center for Arts Education Alexandra Howes*, Jill Tammen* Amy Hewett-Olatunde, EdD LEAP High School COVER DESIGN AND LAYOUT Cheryl Hornstein Megan Losure (Education Sales and Freelance Theatre and Music Educator Services Manager) Alexandra Howes * Past or Present Member of the Twin Cities Academy Park Square Theatre Teacher Advisory Board Dr. Virginia McFerran Perpich Center for Arts Education Kristin Nelson Brooklyn Center High School Mari O’Meara Eden Prairie High School Jennifer Parker Contact Us Falcon Ridge Middle School Maggie Quam Hmong College Prep Academy PARK SQUARE THEATRE 408 Saint Peter Street, Suite 110 Kate Schilling Saint Paul, MN 55102 Mound Westonka High School EDUCATION: 651.291.9196 Jack Schlukebier [email protected] Central High School, retired www.parksquaretheatre.org Tanya Sponholz Prescott High School Jill Tammen Hudson High School, retired If you have any questions or comments about Craig Zimanske this guide or Park Square Theatre’s Education Forest Lake Area High School Program, please contact Mary Finnerty, Director of Education PHONE 651.767.8494 EMAIL [email protected] www.parksquaretheatre.org | page 2 Study Guide Contents The Play 4. -

Modèle Pour Les Mémoires

ÉCOLE DU LOUVRE Emma Danet Le fonds ethnographique des Œuvres Pontificales Missionnaires de Lyon en provenance d’Amérique du Nord conservé au Musée des Confluences: Étude de cas d’un tambour nord-américain Mémoire d’étude (1re année de 2e cycle) Discipline : Muséologie Groupe de recherche : GR16 Collections extra-occidentales présenté sous la direction de Mme Daria Cevoli Membre du jury : Mme Carine Peltier-Caroff Mme Marie-Paule Imberti Juin 2020 Le contenu de ce mémoire est publié sous la licence Creative Commons CC BY NC ND Table des matières Remerciements............................................................................................................................3 Avant-propos...............................................................................................................................4 Introduction.................................................................................................................................5 I. Un tambour d’Amérique(s): étude typologique et iconographique.......................................10 a. Contexte historique et géographique................................................................................10 b. Le don de Mgr Langevin.......................................................................................................13 c. Le tambour: présentation et typologie...................................................................................15 II. Un objet cérémoniel............................................................................................................19 -

China and the West: Music, Representation, and Reception

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Revised Pages China and the West Revised Pages Wanguo Quantu [A Map of the Myriad Countries of the World] was made in the 1620s by Guilio Aleni, whose Chinese name 艾儒略 appears in the last column of the text (first on the left) above the Jesuit symbol IHS. Aleni’s map was based on Matteo Ricci’s earlier map of 1602. Revised Pages China and the West Music, Representation, and Reception Edited by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2017 by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2020 2019 2018 2017 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Yang, Hon- Lun, editor. | Saffle, Michael, 1946– editor. Title: China and the West : music, representation, and reception / edited by Hon- Lun Yang and Michael Saffle. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016045491| ISBN 9780472130313 (hardcover : alk.