Assessing Biological Integrity in Running Waters a Method and Its Rationale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Highfin Carpsucker Carpiodes Velifer

highfin carpsucker Carpiodes velifer Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The first dorsal ray is long and reaches to or beyond Class: Actinopterygii the back of the dorsal fin base. An adult may grow Order: Cypriniformes to 19 and one-half inches in length, but the average length is nine to 10 inches. There is a small, pointed Family: Catostomidae projection at the front of the lower lip. The pelvic fin ILLINOIS STATUS has nine to 10 rays, and the anal fin has eight to nine rays. The back is brown or gray, and the sides are common, native silvery. The scales have dark edges. The pelvic fins are white to orange, and all fins on the lower body are light-colored. The belly is white. The fish has a two-chambered gas bladder. The lateral line is complete. BEHAVIORS The highfin carpsucker lives in creeks and rivers statewide. It is not tolerant of turbidity or siltation. It feeds on small aquatic invertebrates that it finds on the bottom of its water body. Spawning occurs in spring and early summer. It is sometimes seen swimming with its back sticking out of the water. ILLINOIS RANGE © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2020. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. © Uland Thomas Aquatic Habitats rivers and streams Woodland Habitats none Prairie and Edge Habitats none © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2020. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources.. -

SPORT FISH of OHIO Identification DIVISION of WILDLIFE

SPORT FISH OF OHIO identification DIVISION OF WILDLIFE 1 With more than 40,000 miles of streams, 2.4 million acres of Lake Erie and inland water, and 450 miles of the Ohio River, Ohio supports a diverse and abundant fish fauna represented by more than 160 species. Ohio’s fishes come in a wide range of sizes, shapes and colors...and live in a variety of aquatic habitats from our largest lakes and rivers to the smallest ponds and creeks. Approximately one-third of these species can be found in this guide. This fish identification guide provides color illustrations to help anglers identify their catch, and useful tips to help catch more fish. We hope it will also increase your awareness of the diversity of fishes in Ohio. This book also gives information about the life history of 27 of Ohio’s commonly caught species, as well as information on selected threatened and endangered species. Color illustrations and names are also offered for 20 additional species, many of which are rarely caught by anglers, but are quite common throughout Ohio. Fishing is a favorite pastime of many Ohioans and one of the most enduring family traditions. A first fish or day shared on the water are memories that last a lifetime. It is our sincere hope that the information in this guide will contribute significantly to your fishing experiences and understanding of Ohio’s fishes. Good Fishing! The ODNR Division of Wildlife manages the fisheries of more than 160,000 acres of inland water, 7,000 miles of streams, and 2.25 million acres of Lake Erie. -

Spatial Variation in Fish-Tissue Mercury Concentrations in the St. Croix River Basin, Minnesota and Wisconsin, 2004

Prepared in cooperation with the National Park Service Spatial Variation in Fish-Tissue Mercury Concentrations in the St. Croix River Basin, Minnesota and Wisconsin, 2004 Scientific Investigations Report 2006–5063 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Spatial Variation in Fish-Tissue Mercury Concentrations in the St. Croix River Basin, Minnesota and Wisconsin, 2004 By Victoria G. Christensen, Stephen P. Wente, Mark B. Sandheinrich, and Mark E . Brigham Prepared in cooperation with the National Park Service Scientific Investigations Report 2006–5063 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior P. Lynn Scarlett, Acting Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Christensen, V.G., Wente, S.P., Sandheinrich, M.B., and Brigham, M.E., 2006, Spatial variation in fish-tissue mercury concentrations in the St. Croix River Basin, Minnesota and Wisconsin, 2004: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investi- gations Report 2006–5063, 26 p. -

Tennessee Fish Species

The Angler’s Guide To TennesseeIncluding Aquatic Nuisance SpeciesFish Published by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency Cover photograph Paul Shaw Graphics Designer Raleigh Holtam Thanks to the TWRA Fisheries Staff for their review and contributions to this publication. Special thanks to those that provided pictures for use in this publication. Partial funding of this publication was provided by a grant from the United States Fish & Wildlife Service through the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force. Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency Authorization No. 328898, 58,500 copies, January, 2012. This public document was promulgated at a cost of $.42 per copy. Equal opportunity to participate in and benefit from programs of the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency is available to all persons without regard to their race, color, national origin, sex, age, dis- ability, or military service. TWRA is also an equal opportunity/equal access employer. Questions should be directed to TWRA, Human Resources Office, P.O. Box 40747, Nashville, TN 37204, (615) 781-6594 (TDD 781-6691), or to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office for Human Resources, 4401 N. Fairfax Dr., Arlington, VA 22203. Contents Introduction ...............................................................................1 About Fish ..................................................................................2 Black Bass ...................................................................................3 Crappie ........................................................................................7 -

RFP No. 212F for Endangered Species Research Projects for the Prairie Chub

1 RFP No. 212f for Endangered Species Research Projects for the Prairie Chub Final Report Contributing authors: David S. Ruppel, V. Alex Sotola, Ozlem Ablak Gurbuz, Noland H. Martin, and Timothy H. Bonner Addresses: Department of Biology, Texas State University, San Marcos, Texas 78666 (DSR, VAS, NHM, THB) Kirkkonaklar Anatolian High School, Turkish Ministry of Education, Ankara, Turkey (OAG) Principal investigators: Timothy H. Bonner and Noland H. Martin Email: [email protected], [email protected] Date: July 31, 2017 Style: American Fisheries Society Funding sources: Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, Turkish Ministry of Education- Visiting Scholar Program (OAG) Summary Four hundred mesohabitats were sampled from 36 sites and 20 reaches within the upper Red River drainage from September 2015 through September 2016. Fishes (N = 36,211) taken from the mesohabitats represented 14 families and 49 species with the most abundant species consisting of Red Shiner Cyprinella lutrensis, Red River Shiner Notropis bairdi, Plains Minnow Hybognathus placitus, and Western Mosquitofish Gambusia affinis. Red River Pupfish Cyprinodon rubrofluviatilis (a species of greatest conservation need, SGCN) and Plains Killifish Fundulus zebrinus were more abundant within prairie streams (e.g., swift and shallow runs with sand and silt substrates) with high specific conductance. Red River Shiner (SGCN), Prairie Chub Macrhybopsis australis (SGCN), and Plains Minnow were more abundant within prairie 2 streams with lower specific conductance. The remaining 44 species of fishes were more abundant in non-prairie stream habitats with shallow to deep waters, which were more common in eastern tributaries of the upper Red River drainage and Red River mainstem. Prairie Chubs comprised 1.3% of the overall fish community and were most abundant in Pease River and Wichita River. -

Fish of Greatest Conservation Need

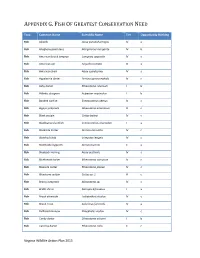

APPENDIX G. FISH OF GREATEST CONSERVATION NEED Taxa Common Name Scientific Name Tier Opportunity Ranking Fish Alewife Alosa pseudoharengus IV a Fish Allegheny pearl dace Margariscus margarita IV b Fish American brook lamprey Lampetra appendix IV c Fish American eel Anguilla rostrata III a Fish American shad Alosa sapidissima IV a Fish Appalachia darter Percina gymnocephala IV c Fish Ashy darter Etheostoma cinereum I b Fish Atlantic sturgeon Acipenser oxyrinchus I b Fish Banded sunfish Enneacanthus obesus IV c Fish Bigeye jumprock Moxostoma ariommum III c Fish Black sculpin Cottus baileyi IV c Fish Blackbanded sunfish Enneacanthus chaetodon I a Fish Blackside darter Percina maculata IV c Fish Blotched chub Erimystax insignis IV c Fish Blotchside logperch Percina burtoni II a Fish Blueback Herring Alosa aestivalis IV a Fish Bluebreast darter Etheostoma camurum IV c Fish Blueside darter Etheostoma jessiae IV c Fish Bluestone sculpin Cottus sp. 1 III c Fish Brassy Jumprock Moxostoma sp. IV c Fish Bridle shiner Notropis bifrenatus I a Fish Brook silverside Labidesthes sicculus IV c Fish Brook Trout Salvelinus fontinalis IV a Fish Bullhead minnow Pimephales vigilax IV c Fish Candy darter Etheostoma osburni I b Fish Carolina darter Etheostoma collis II c Virginia Wildlife Action Plan 2015 APPENDIX G. FISH OF GREATEST CONSERVATION NEED Fish Carolina fantail darter Etheostoma brevispinum IV c Fish Channel darter Percina copelandi III c Fish Clinch dace Chrosomus sp. cf. saylori I a Fish Clinch sculpin Cottus sp. 4 III c Fish Dusky darter Percina sciera IV c Fish Duskytail darter Etheostoma percnurum I a Fish Emerald shiner Notropis atherinoides IV c Fish Fatlips minnow Phenacobius crassilabrum II c Fish Freshwater drum Aplodinotus grunniens III c Fish Golden Darter Etheostoma denoncourti II b Fish Greenfin darter Etheostoma chlorobranchium I b Fish Highback chub Hybopsis hypsinotus IV c Fish Highfin Shiner Notropis altipinnis IV c Fish Holston sculpin Cottus sp. -

Information on the NCWRC's Scientific Council of Fishes Rare

A Summary of the 2010 Reevaluation of Status Listings for Jeopardized Freshwater Fishes in North Carolina Submitted by Bryn H. Tracy North Carolina Division of Water Resources North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources Raleigh, NC On behalf of the NCWRC’s Scientific Council of Fishes November 01, 2014 Bigeye Jumprock, Scartomyzon (Moxostoma) ariommum, State Threatened Photograph by Noel Burkhead and Robert Jenkins, courtesy of the Virginia Division of Game and Inland Fisheries and the Southeastern Fishes Council (http://www.sefishescouncil.org/). Table of Contents Page Introduction......................................................................................................................................... 3 2010 Reevaluation of Status Listings for Jeopardized Freshwater Fishes In North Carolina ........... 4 Summaries from the 2010 Reevaluation of Status Listings for Jeopardized Freshwater Fishes in North Carolina .......................................................................................................................... 12 Recent Activities of NCWRC’s Scientific Council of Fishes .................................................. 13 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part I, Ohio Lamprey .............................................. 14 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part II, “Atlantic” Highfin Carpsucker ...................... 17 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part III, Tennessee Darter ...................................... 20 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part -

Urban Areas Have Ecological Integrity(3-8)

Can urban areas have ecological integrity? Reed F. Noss INTRODUCTION The question of whether urban areas can offer a habitat and wildlife within and around urban areas, semblance of the natural world – a vestige (at least) where most people live. But, if we embark on this of ecological integrity – is an important one to many venture, how do we know if we are succeeding? people who live in these areas. As more and more of There are both social and biological measures of the world becomes urbanized, this question becomes success. The social measures include increased highly relevant to the broader mission of maintain- awareness of and appreciation for native wildlife ing the Earth’s biological diversity. and healthy ecosystems. The biological measures are Most people, especially when young, are attracted the subject of my talk this morning; I will focus on to the natural world and living things, Ed Wilson adaptation of the ecological integrity concept to called this attraction “biophilia.” And entire books urban and suburban areas and the role of connectiv- have been written about it – one, for example, by ity (i.e. wildlife corridors) in promoting ecological Steve Kellert, who also appears in this morning’s integrity. program. Personally, I share Wilson’s speculation that biophilia has a genetic basis. Some people are Urban Ecological Integrity biophilic than others. This tendency is very likely Ecological integrity is what we might call an heritable, although it certainly is influenced by the “umbrella concept,” embracing all that is good and environment, particularly by early experiences. My right in ecosystems. -

2.0 Managing Native Mesic Forest Remnants

2.0 MANAGING NATIVE MESIC FOREST REMNANTS Photo by Amy Tsuneyoshi 2.1 RESTORATION CONCEPTS AND PRINCIPLES The word restore means “to bring back…into a former or original state” (Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary 1977). For the purposes of this book, forest restoration assumes that some semblance of a native forest remains and the restoration process is one of removing the causes for that degradation and returning the forest back to a former intact native state. More formally, restoration is defined as: The return of an ecosystem to its historical trajectory by removing or modifying a specific disturbance, and thereby allowing ecological processes to bring about an independent recovery (Society for Ecological Restoration International Science and Policy Working Group 2004). The term native integrity used throughout this book refers to this continuum of intactness. An area very high in native integrity is fully intact. James Karr (1996) defines biological integrity as: The ability to support and maintain a balanced, integrated, adaptive biological system having the full range of elements (genes, species, and assemblages) and processes (mutation, demography, biotic interactions, nutrient and energy dynamics, and metapopulation processes) expected in the natural habitat of a region. This standard of biological integrity is admittedly beyond the reach of many restoration projects given some of the irreversible effects of invasive plants and animals as well as a lack of knowledge of how an ecosystem worked in the first place. Nonetheless, the goal of a restoration effort should be a restored native area that is healthy, viable, and self-sustaining requiring a minimum amount of active management in the long-term. -

ECOLOGY of NORTH AMERICAN FRESHWATER FISHES

ECOLOGY of NORTH AMERICAN FRESHWATER FISHES Tables STEPHEN T. ROSS University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London © 2013 by The Regents of the University of California ISBN 978-0-520-24945-5 uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 1 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 2 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM TABLE 1.1 Families Composing 95% of North American Freshwater Fish Species Ranked by the Number of Native Species Number Cumulative Family of species percent Cyprinidae 297 28 Percidae 186 45 Catostomidae 71 51 Poeciliidae 69 58 Ictaluridae 46 62 Goodeidae 45 66 Atherinopsidae 39 70 Salmonidae 38 74 Cyprinodontidae 35 77 Fundulidae 34 80 Centrarchidae 31 83 Cottidae 30 86 Petromyzontidae 21 88 Cichlidae 16 89 Clupeidae 10 90 Eleotridae 10 91 Acipenseridae 8 92 Osmeridae 6 92 Elassomatidae 6 93 Gobiidae 6 93 Amblyopsidae 6 94 Pimelodidae 6 94 Gasterosteidae 5 95 source: Compiled primarily from Mayden (1992), Nelson et al. (2004), and Miller and Norris (2005). uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 3 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM TABLE 3.1 Biogeographic Relationships of Species from a Sample of Fishes from the Ouachita River, Arkansas, at the Confl uence with the Little Missouri River (Ross, pers. observ.) Origin/ Pre- Pleistocene Taxa distribution Source Highland Stoneroller, Campostoma spadiceum 2 Mayden 1987a; Blum et al. 2008; Cashner et al. 2010 Blacktail Shiner, Cyprinella venusta 3 Mayden 1987a Steelcolor Shiner, Cyprinella whipplei 1 Mayden 1987a Redfi n Shiner, Lythrurus umbratilis 4 Mayden 1987a Bigeye Shiner, Notropis boops 1 Wiley and Mayden 1985; Mayden 1987a Bullhead Minnow, Pimephales vigilax 4 Mayden 1987a Mountain Madtom, Noturus eleutherus 2a Mayden 1985, 1987a Creole Darter, Etheostoma collettei 2a Mayden 1985 Orangebelly Darter, Etheostoma radiosum 2a Page 1983; Mayden 1985, 1987a Speckled Darter, Etheostoma stigmaeum 3 Page 1983; Simon 1997 Redspot Darter, Etheostoma artesiae 3 Mayden 1985; Piller et al. -

Aquatic Fish Report

Aquatic Fish Report Acipenser fulvescens Lake St urgeon Class: Actinopterygii Order: Acipenseriformes Family: Acipenseridae Priority Score: 27 out of 100 Population Trend: Unknown Gobal Rank: G3G4 — Vulnerable (uncertain rank) State Rank: S2 — Imperiled in Arkansas Distribution Occurrence Records Ecoregions where the species occurs: Ozark Highlands Boston Mountains Ouachita Mountains Arkansas Valley South Central Plains Mississippi Alluvial Plain Mississippi Valley Loess Plains Acipenser fulvescens Lake Sturgeon 362 Aquatic Fish Report Ecobasins Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - Arkansas River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - St. Francis River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - White River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain (Lake Chicot) - Mississippi River Habitats Weight Natural Littoral: - Large Suitable Natural Pool: - Medium - Large Optimal Natural Shoal: - Medium - Large Obligate Problems Faced Threat: Biological alteration Source: Commercial harvest Threat: Biological alteration Source: Exotic species Threat: Biological alteration Source: Incidental take Threat: Habitat destruction Source: Channel alteration Threat: Hydrological alteration Source: Dam Data Gaps/Research Needs Continue to track incidental catches. Conservation Actions Importance Category Restore fish passage in dammed rivers. High Habitat Restoration/Improvement Restrict commercial harvest (Mississippi River High Population Management closed to harvest). Monitoring Strategies Monitor population distribution and abundance in large river faunal surveys in cooperation -

A Fish Habitat Partnership

A Fish Habitat Partnership Strategic Plan for Fish Habitat Conservation in Midwest Glacial Lakes Engbretson Underwater Photography September 30, 2009 This page intentionally left blank. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 I. BACKGROUND 7 II. VALUES OF GLACIAL LAKES 8 III. OVERVIEW OF IMPACTS TO GLACIAL LAKES 9 IV. AN ECOREGIONAL APPROACH 14 V. MULTIPLE INTERESTS WITH COMMON GOALS 23 VI. INVASIVES SPECIES, CLIMATE CHANGE 23 VII. CHALLENGES 25 VIII. INTERIM OBJECTIVES AND TARGETS 26 IX. INTERIM PRIORITY WATERSHEDS 29 LITERATURE CITED 30 APPENDICES I Steering Committee, Contributing Partners and Working Groups 33 II Fish Habitat Conservation Strategies Grouped By Themes 34 III Species of Greatest Conservation Need By Level III Ecoregions 36 Contact Information: Pat Rivers, Midwest Glacial Lakes Project Manager 1601 Minnesota Drive Brainerd, MN 56401 Telephone 218-327-4306 [email protected] www.midwestglaciallakes.org 3 Executive Summary OUR MISSION The mission of the Midwest Glacial Lakes Partnership is to work together to protect, rehabilitate, and enhance sustainable fish habitats in glacial lakes of the Midwest for the use and enjoyment of current and future generations. Glacial lakes (lakes formed by glacial activity) are a common feature on the midwestern landscape. From small, productive potholes to the large windswept walleye “factories”, glacial lakes are an integral part of the communities within which they are found and taken collectively are a resource of national importance. Despite this value, lakes are commonly treated more as a commodity rather than a natural resource susceptible to degradation. Often viewed apart from the landscape within which they occupy, human activities on land—and in water—have compromised many of these systems.