Religious Freedom Under the Meiji Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

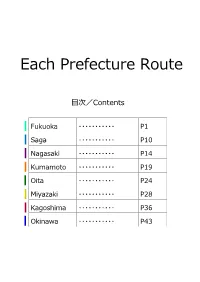

Each Prefecture Route

Each Prefecture Route 目次/Contents Fukuoka ・・・・・・・・・・・ P1 Saga ・・・・・・・・・・・ P10 Nagasaki ・・・・・・・・・・・ P14 Kumamoto ・・・・・・・・・・・ P19 Oita ・・・・・・・・・・・ P24 Miyazaki ・・・・・・・・・・・ P28 Kagoshima ・・・・・・・・・・・ P36 Okinawa ・・・・・・・・・・・ P43 福岡県/Fukuoka 福岡県ルート① 福岡の食と自然を巡る旅~インスタ映えする自然の名所と福岡の名産を巡る~(1 泊 2 日) Fukuoka Route① Around tour Local foods and Nature of Fukuoka ~Around tour Local speciality and Instagrammable nature sightseeing spot~ (1night 2days) ■博多駅→(地下鉄・JR 筑肥線/約 40 分)→筑前前原駅→(タクシー/約 30 分) □Hakata sta.→(Subway・JR Chikuhi line/about 40min.)→Chikuzenmaebaru sta.→(Taxi/about 30min.) 【糸島市/Itoshima city】 ・桜井二見ヶ浦/Sakurai-futamigaura (Scenic spot) ■(タクシー/約 30 分)→筑前前原駅→(地下鉄/約 20 分)→下山門駅→(徒歩/約 15 分) □(Taxi/about 30min.)→Chikuzenmaebaru sta.→(Subway/about 20min.)→Shimoyamato sta.→(About 15min. on foot) 【福岡市/Fukuoka city】 ・生の松原・元寇防塁跡/Ikino-matsubara・Genkou bouruiato ruins (Stone wall) ■(徒歩/約 15 分)→下山門駅→(JR 筑肥線/約 5 分)→姪浜駅→(西鉄バス/約 15 分)→能古渡船場→(市営渡船/約 15 分)→ 能古島→(西鉄バス/約 15 分)→アイランドパーク 1 □(About 15min. on foot)→Shimoyamato sta.→(JR Chikuhi line/about 5min.)→Meinohama sta.→ (Nishitetsu bus/about 15min.)→Nokotosenba→(Ferry/about 15min.)→Nokonoshima→(Nishitetsu bus/about 15min.)→ Island park 【福岡市/Fukuoka city】 ・能古島アイランドパーク/Nokonoshima island Park ■アイランドパーク→(西鉄バス/約 15 分)→能古島→(市営渡船/約 15 分)→能古渡船場→(西鉄バス/約 30 分)→天神 □Island park→(Nishitetsu bus/about 15min.)→Nokonoshima→(Ferry/about 15min.)→Nokotosenba→ (Nishitetsu bus/about 30min.)→Tenjin 【天神・中州/Tenjin・Nakasu】 ・屋台/Yatai (Food stall) (宿泊/Accommodation)福岡市/Fukuoka city ■博多駅→(徒歩/約 5 分)→博多バスターミナル→(西鉄バス/約 80 分)→甘木駅→(甘木観光バス/約 20 分)→秋月→(徒歩/約 15 分) □Hakata sta.→(About 5min. on foot)→Hakata B.T.→(Nishitetsu bus/about 80min)→Amagi sta.→ (Amagi kanko bus/about 20min.)→Akizuki→(About 15min. -

Ecology, Behavior and Conservation of the Japanese Mamushi Snake, Gloydius Blomhoffii: Variation in Compromised and Uncompromised Populations

ECOLOGY, BEHAVIOR AND CONSERVATION OF THE JAPANESE MAMUSHI SNAKE, GLOYDIUS BLOMHOFFII: VARIATION IN COMPROMISED AND UNCOMPROMISED POPULATIONS By KIYOSHI SASAKI Bachelor of Arts/Science in Zoology Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK 1999 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2006 ECOLOGY, BEHAVIOR AND CONSERVATION OF THE JAPANESE MAMUSHI SNAKE, GLOYDIUS BLOMHOFFII: VARIATION IN COMPROMISED AND UNCOMPROMISED POPULATIONS Dissertation Approved: Stanley F. Fox Dissertation Adviser Anthony A. Echelle Michael W. Palmer Ronald A. Van Den Bussche A. Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I sincerely thank the following people for their significant contribution in my pursuit of a Ph.D. degree. I could never have completed this work without their help. Dr. David Duvall, my former mentor, helped in various ways until the very end of his career at Oklahoma State University. This study was originally developed as an undergraduate research project under Dr. Duvall. Subsequently, he accepted me as his graduate student and helped me expand the project to this Ph.D. research. He gave me much key advice and conceptual ideas for this study. His encouragement helped me to get through several difficult times in my pursuit of a Ph.D. degree. He also gave me several books as a gift and as an encouragement to complete the degree. Dr. Stanley Fox kindly accepted to serve as my major adviser after Dr. Duvall’s departure from Oklahoma State University and involved himself and contributed substantially to this work, including analysis and editing. -

Arquitetura E Tática Militar: Fortalezas Japonesas Dos Séculos XVI-XVII

1 Universidade de Brasília Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo Programa de Pós-graduação (PPG-FAU) Departamento de Teoria e História em Arquitetura e Urbanismo Arquitetura e tática militar: Fortalezas japonesas dos séculos XVI-XVII Dissertação de Mestrado Brasília, 2011 2 3 Joanes da Silva Rocha Arquitetura e tática militar: Fortalezas japonesas dos séculos XVI-XVII Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de Brasília como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Arquitetura e Urbanismo. Orientadora: Prof.ª Dr.ª Sylvia Ficher. Brasília, 2011 4 5 Joanes da Silva Rocha Arquitetura e tática militar: Fortalezas japonesas dos séculos XVI-XVII Esta dissertação foi julgada e aprovada no dia 9 de fevereiro de 2011 para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Arquitetura e Urbanismo no Programa de Pós-graduação da Universidade de Brasília (PPG-FAU-UnB) BANCA EXAMINADORA Prof.ª Dr.ª Sylvia Ficher (Orientadora) Departamento de Teoria e História em Arquitetura e Urbanismo FAU/UnB Prof. Dr. Pedro Paulo Palazzo Departamento de Teoria e História em Arquitetura e Urbanismo FAU/UnB Prof. Dr. José Galbinski Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo UniCEUB Prof.ª Dr.ª Maria Fernanda Derntl Departamento de Teoria e História em Arquitetura e Urbanismo FAU/UnB Suplente 6 7 Gratidão aos meus pais Joaquim e Nelci pelo constante apoio e dedicação; Ao carinho de minha irmã Jeane; Aos professores, especialmente à Sylvia Ficher e Pedro Paulo, que guiaram-me neste jornada de pesquisa; Obrigado Dionisio França, que de Nagoya muito me auxiliou e à Kamila, parentes e amigos que me incentivaram. -

Endangered Traditional Beliefs in Japan: Influences on Snake Conservation

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 5(3):474–485. Submitted: 26 October 2009; 18 September 2010. ENDANGERED TRADITIONAL BELIEFS IN JAPAN: INFLUENCES ON SNAKE CONSERVATION 1 2 3 KIYOSHI SASAKI , YOSHINORI SASAKI , AND STANLEY F. FOX 1Department of Biology, Loyola University Maryland, Baltimore, Maryland 21210, USA, e-mail: [email protected] 242-9 Nishi 24 Minami 1, Obihiro, Hokkaido 080-2474, Japan 3Department of Zoology, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, Oklahoma 74078, USA ABSTRACT.—Religious beliefs and practices attached to the environment and specific organisms are increasingly recognized to play a critical role for successful conservation. We herein document a case study in Japan with a focus on the beliefs associated with snakes. In Japan, snakes have traditionally been revered as a god, a messenger of a god, or a creature that brings a divine curse when a snake is harmed or a particular natural site is disturbed. These strong beliefs have discouraged people from harming snakes and disturbing certain habitats associated with a snake god. Thus, traditional beliefs and cultural mores are often aligned with today’s conservation ethics, and with their loss wise conservation of species and their habitats may fall by the wayside. The erosion of tradition is extensive in modern Japan, which coincides with increased snake exploitation, killing, and reduction of habitat. We recommend that conservation efforts of snakes (and other biodiversity) of Japan should include immediate, cooperative efforts to preserve and revive traditional beliefs, to collect ecological and geographical data necessary for effective conservation and management activities, and to involve the government to make traditional taboos formal institutions. -

Japan: an Attempt at Interpretation

JAPAN: AN ATTEMPT AT INTERPRETATION BY LAFCADIO HEARN 1904 Contents CHAPTER PAGE I. DIFFICULTIES.........................1 II. STRANGENESS AND CHARM................5 III. THE ANCIENT CULT....................21 IV. THE RELIGION OF THE HOME............33 V. THE JAPANESE FAMILY.................55 VI. THE COMMUNAL CULT...................81 VII. DEVELOPMENTS OF SHINTO.............107 VIII. WORSHIP AND PURIFICATION...........133 IX. THE RULE OF THE DEAD...............157 X. THE INTRODUCTION OF BUDDHISM.......183 XI. THE HIGHER BUDDHISM................207 XII. THE SOCIAL ORGANIZATION............229 XIII. THE RISE OF THE MILITARY POWER.....259 XIV. THE RELIGION OF LOYALTY............283 XV. THE JESUIT PERIL...................303 XVI. FEUDAL INTEGRATION.................343 XVII. THE SHINTO REVIVAL.................367 XVIII. SURVIVALS..........................381 XIX. MODERN RESTRAINTS..................395 XX. OFFICIAL EDUCATION.................419 XXI. INDUSTRIAL DANGER..................443 XXII. REFLECTIONS........................457 APPENDIX...........................481 BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTES..............487 INDEX..............................489 "Perhaps all very marked national characters can be traced back to a time of rigid and pervading discipline" --WALTER BAGEHOT. [1] DIFFICULTIES A thousand books have been written about Japan; but among these,--setting aside artistic publications and works of a purely special character,--the really precious volumes will be found to number scarcely a score. This fact is due to the immense difficulty of perceiving and comprehending what underlies the surface of Japanese life. No work fully interpreting that life,--no work picturing Japan within and without, historically and socially, psychologically and ethically,--can be written for at least another fifty years. So vast and intricate the subject that the united labour of a generation of scholars could not exhaust it, and so difficult that the number of scholars willing to devote their time to it must always be small. -

The Textile Terminology in Ancient Japan

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Centre for Textile Research Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD 2017 The exT tile Terminology in Ancient Japan Mari Omura Gangoji Institute for Research of Cultural Property Naoko Kizawa Gangoji Institute for Research of Cultural Property Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Omura, Mari and Kizawa, Naoko, "The exT tile Terminology in Ancient Japan" (2017). Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 28. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/28 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Textile Research at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Textile Terminology in Ancient Japan Mari Omura, Gangoji Institute for Research of Cultural Property Naoko Kizawa, Gangoji Institute for Research of Cultural Property In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, ed. Salvatore Gaspa, Cécile Michel, & Marie-Louise Nosch (Lincoln, NE: Zea Books, 2017), pp. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Jade, amber, obsidian and serpentinite: the social context of exotic stone exchange networks in central Japan during the late middle Jômon period Bausch, Ilona How to cite: Bausch, Ilona (2003) Jade, amber, obsidian and serpentinite: the social context of exotic stone exchange networks in central Japan during the late middle Jômon period, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4022/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. JadCy Ambery Obsidian and Serpentinite: the social context of exotic stone exchange networks in Central Japan during the Late Middle Jomon period by Ilona Bausch A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies, University of Durham 31 December 2003 I I JAN 7005 117 ABSTRACT The social context of exotic stone exchange nefworfcs in Centml Japan during the Late Middle Jomon period llona Bausch This dissertation presents a holistic, contextual approach to long-distance exchange networks in Central Japan ca. -

Come Celebrate

JANUARY 2009 | VOL. 15, NO. 1 LEGACIES Honoring our heritage. Embracing our diversity. Sharing our future. LEGACIES IS A PUBLICATION OF THE JAPANESE CULTURAL CENTER OF HAWAI`I, 2454 SOUTH BERETANIA STREET, HONOLULU, HI 96826 ComeTHE YEARcelebrate OF THE 2454 South Beretania Street Honolulu, HI 96826 tel: (808) 945-7633 fax: (808) 944-1123 Ox KIKAIDAMANIA ‘09 OFFICE HOURS Return of the Kikaida Brothers! Monday - Saturday MEET HAWai’i’s FAVORITE 8:00 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. JAPANESE SUPERHEROES! GALLERY HOURS Two 30-minute shows with Tuesday - Saturday audience participation. 10:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m. 11 A.M. AND 2:30 P.M. RESOURCE CENTER HOURS See page 7 for more information. Wednesday - Friday 10:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m. Saturday 10:00 a.m. - 1:00 p.m. Actor Ban Daisuke, GIFT SHOP HOURS who starred in Inazuman and Tuesday - Saturday Kikaida, will be 10:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m. available to sign autographs. Mission Statement: To be a vibrant resource, strengthening our diverse community by educating present and future generations in the evolving New Year’s ‘Ohana Festival Japanese American experience in Hawai‘i. We do this through Sunday, January 11, 2009 • 10 A.M. – 4 P.M. JAPANESE CULtural Center of Hawai‘i relevant programming, meaningful - community service and & MO‘ili‘ili FIELD innovative partnerships that FREE ADMISSION enhance the understanding and PARKING: A complimentary shuttle service will run between the parking celebration of our heritage, structure at the University of Hawai‘i at Ma-noa and the Japanese Cultural culture and love of the land. -

September 2010 (Pdf)

Tō-Ron Monthly Newsletter of the Northern California Japanese Sword Club General Meeting: 12:30pm to 3:30pm September 19, 2010 September 2010 NCJSC P.O. Box 7156 San Carlos, CA 94070 www.ncjsc.org [email protected] September Topic: Kagoshima - Satsuma Contents Kagoshima city, capitol of Kagoshima prefecture in Southern Kyushu. Currently with a population of some 600,000 it became the chief town of Satsuma han • 2010 Monthly Topics when the Shimazu family built a castle there in 1602. Because of the defeat at • Directors & Committees Sekigahara the Shimazu family holdings were greatly reduced, forcing them to • Announcements / Request give up ancestral lands. Nearly all the families under their control chose to live in reduced circumstances under the Shimazu rather than stay with their fiefs and serve new lords. Already remote, this new Satsuma became a country of Samu- rai-farmers with their own unique dialect and a decidedly martial culture. • Monthly display See Page 3 for full details • Two tsuba by Musashi • Translation Exercise • The Hizen School • NCJSC Publications October Meeting: Topic: Kuwana - Isa, Muramasa • Tampa Sword Show Kuwana, castle town of the Ise family and gateway to the Grand Shrine at Ise. Sadahide, Munehide, Munemasa, Munetomo, Masayuki Mitsusada of the Ha- zama school made tsuba nearby in Kameyama, while Nobutoki worked in Ku- wana itself. Kanezane, Kanenaga, Kanekore and Masamori swordmakers of the Ujiin school worked here. Also Masashige, Masazane, ……….. See Page 3 for full details @ 2010—All rights reserved No part of this newsletter may be copied, or used for other that personal use, without written permission from the NCJSC. -

Eastern· Asia and Oceania

I Eastern· Asia and Oceania WILHELM G. SOLHEIM II TENTH PACIFIC SCIENCE CONGRESS A general notice of the Tenth Pacific Science Congress was presented in this section of the last news issue of Asian Perspectives. There are to be four sessions jointly sponsored by the Section of anthropology and Social Sciences of the Congress and the Far-Eastern Prehistory Association. The organizer of this Division is Dr Kenneth P. Emory, Department of Anthropology, Bernice P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu 17, Hawaii and the Co-organizer is Dr Wilhelm G. Solheim II, FEPA, Department ofAnthropology and Archreology, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida. Three ofthe sessions are symposia; these are: 'Geochronology: Methods and Results', Convener-Wilhelm G. Solheim II; 'Current Research in Pacific Islands Archreology', Convener-Kenneth P. Emory; and 'Trade Stone ware and Porcelain in Southeast Asia', Convener-Robert P. Griffing, Jr., Director, Honolulu Academy of Arts, Honolulu, Hawaii. The fourth session will be 'Contri buted Papers on Far Eastern Archreology', with its Chairman Roger Duff, Director, Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, New Zealand. There are a number of other symposia in the Anthropology and Social Science Section which will be of particular interest to the archreologist. A detailed report of the meetings will appear in the Winter 1961 issue (Vol. V, No.2) of Asian Perspect£ves. UNIVERSITY PROGRAlVIMES IN FAR-EASTERN PREHISTORY Academic interest in the inclusion of Oceanian and Southeast Asian prehistoric archreology in the university curriculum is continuing to increase. In 1960 the Australian National University indicated their intention of including this in their programme with the selection of Jack Golson as a Fellow on the staff of their Department of Anthropology and Sociology. -

The Sacred Kumano Pilgrimage World Heritage: the Origin of Tourism in Japan Is Related to Cultural Landscape

The Sacred Kumano Pilgrimage World Heritage: the origin of tourism in Japan is related to cultural landscape Lorenz Poggendorf Keywords: Kii Mountain Range, Kumano Sanzan, sacred sites, tourism, cultural landscape Abstract: In Japan, due to nature-worship as part of Shinto belief and mountain retreats of esoteric Buddhism, certain natural sites have been revered as being sacred. This is not only the backdrop of ancient pilgrimage in the Kii Mountain Range, but also the key to understand the potential of this World Heritage landscape for sustainable tourism. For this reason, this paper emphasizes to notice and balance various aspects of the region for its future success as a high-quality tourist destination. 1. Introduction The Kii Peninsula in central Japan, stretching over parts of Mie, Wakayama and Nara prefectures, has a scenic mountain range covered with lush green forests, crossed by clear streams. Not too far from the ancient capitals of Nara and Kyoto, and provided with revered shrines and temples, it has always been a popular destination for pilgrimage, one of the earliest forms of tourism, both in Japanese and world history. The Sacred Kumano Pilgrimage route has three major sacred spots, where various beliefs merge in a mountain worship called Shugendo 1 (McGuire 2013). By touching on its historical roots, the goal of this paper is to explain what this area makes actually so unique, what should be scrutinized –– and how its cultural landscape and World Heritage status could be further used for sustainable tourism. 2. Sacred Sites and Pilgrimage Routes with a long history as a mountain retreat Major spots are the famous Shingon Buddhist temple complex Kōyasan in the North, Kumano Hongu Taisha in the centre and Kumano Sanzan towards the Pacific Ocean in the South (Figure 1). -

Temple Treasures of Japan

5f?a®ieiHas3^ C-'Vs C3ts~^ O ft Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 with funding from Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/details/ternpletreasureso00pier_0 Bronze Figure of Amida at Kamakura. Cast by Ono Goroyemon, 1252 A. D. Foundation-stones of Original Temple seen to left of Illustration. Photographed by the Author. TEMPLE TREASURES OF JAPAN BY GARRETT CHATFIELD PIER NEW YORK FREDERIC FAIRCHILD SHERMAN MCMXIV Copyright, 1914, by Frederic Fairchild Sherman ILLUSTRATIONS Bronze Figure of Amida at Kamakura. Cast by Ono Goroyemon, 1252 A. D. Foundation- stones of Original Temple seen to left of Illustration Frontispiece Facing Pig. Page 1. Kala, Goddess of Art. Dry lacquer. Tempyo Era, 728-749. Repaired during the Kamakura Epoch (13th Century). Akishinodera, Yamato .... 16 2. Niomon. Wood, painted. First Nara Epoch (711 A. D.). Horyuji, Nara 16 3. Kondo or Main Hall. First Nara Epoch (71 1 A. D.). Horyuji, Nara 16 4. Kwannon. Copper, gilt. Suiko Period (591 A. D.). Imperial Household Collection. Formerly Horyuji, Nara 16 5. Shaka Trinity. Bronze. Cast by Tori (623 A. D.) Kondo Horyuji 17 6. Yakushi. Bronze. Cast by Tori (607 A. D.). Kondo, Horyuji 17 7. Kwannon. Wood. Korean (?) Suiko Period, 593-628, or Earlier. Nara Museum, Formerly in the Kondo, Horyuji 17 8. Kwannon. Wood, Korean (?) Suiko Period, 593-628, or Earlier. Main Deity of the Yumedono, Horyuji . 17 9. Portable Shrine called Tamamushi or “Beetle’s Wing” Shrine. Wood painted. Suiko Period, 593- 628 A. D. Kondo, Horyuji 32 10. Kwannon. Wood. Attributed to Shotoku Taishi, Suiko Period, 593-628. Main Deity of the Nunnery of Chuguji.