Oskar Loorits: Byzantine Cultural Relations and Practical Application of Folklore Archives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections on the Production of the Finno-Ugric Exhibitions at the Estonian National Museum

THE ETHICS OF ETHNOGRAPHIC ATTRACTION: REFLECTIONS ON THE PRODUCTION OF THE FINNO-UGRIC EXHIBITIONS AT THE ESTONIAN NATIONAL MUSEUM SVETLANA KARM Researcher Estonian National Museum Veski 32, 51014 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ART LEETE Professor of Ethnology University of Tartu Ülikooli 18, 50090 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT We intend to explore* the production of the Finno-Ugric exhibitions at the Esto- nian National Museum. Our particular aim is to reveal methodological changes of ethnographic reproduction and to contextualise the museum’s current efforts in ideologically positioning of the permanent exhibition. Through historical–herme- neutical analysis we plan to establish particular museological trends at the Esto- nian National Museum that have led curators to the current ideological position. The history of the Finno-Ugric displays at the Estonian National Museum and comparative analysis of international museological practices enable us to reveal and interpret different approaches to ethnographic reconstructions. When exhib- iting indigenous cultures, one needs to balance ethnographic charisma with the ethics of display. In order to employ the approach of ethical attraction, curators must comprehend indigenous cultural logic while building up ethnographic rep- resentations. KEYWORDS: Finno-Ugric • permanent exhibition • museum • ethnography • ethics INTRODUCTION At the current time the Estonian National Museum (ENM) is going through the process of preparing a new permanent exhibition space. The major display will be dedicated to Estonian cultural developments. A smaller, although still significant, task is to arrange the Finno-Ugric permanent exhibition. The ENM has been involved in research into the Finno-Ugric peoples as kindred ethnic groups to the Estonians since the museum was * This research was supported by the European Union through the European Regional Devel- opment Fund (Centre of Excellence in Cultural Theory, CECT), and by the Estonian Ministry of Education and Research (projects PUT590 and ETF9271). -

Estonian Academy of Sciences Yearbook 2014 XX

Facta non solum verba ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES YEAR BOOK ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ESTONICAE XX (47) 2014 TALLINN 2015 ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES The Year Book was compiled by: Margus Lopp (editor-in-chief) Galina Varlamova Ülle Rebo, Ants Pihlak (translators) ISSN 1406-1503 © EESTI TEADUSTE AKADEEMIA CONTENTS Foreword . 5 Chronicle . 7 Membership of the Academy . 13 General Assembly, Board, Divisions, Councils, Committees . 17 Academy Events . 42 Popularisation of Science . 48 Academy Medals, Awards . 53 Publications of the Academy . 57 International Scientific Relations . 58 National Awards to Members of the Academy . 63 Anniversaries . 65 Members of the Academy . 94 Estonian Academy Publishers . 107 Under and Tuglas Literature Centre of the Estonian Academy of Sciences . 111 Institute for Advanced Study at the Estonian Academy of Sciences . 120 Financial Activities . 122 Associated Institutions . 123 Associated Organisations . 153 In memoriam . 200 Appendix 1 Estonian Contact Points for International Science Organisations . 202 Appendix 2 Cooperation Agreements with Partner Organisations . 205 Directory . 206 3 FOREWORD The Estonian science and the Academy of Sciences have experienced hard times and bearable times. During about the quarter of the century that has elapsed after regaining independence, our scientific landscape has changed radically. The lion’s share of research work is integrated with providing university education. The targets for the following seven years were defined at the very start of the year, in the document adopted by Riigikogu (Parliament) on January 22, 2014 and entitled “Estonian research and development and innovation strategy 2014- 2020. Knowledge-based Estonia”. It starts with the acknowledgement familiar to all of us that the number and complexity of challenges faced by the society is ever increasing. -

The Ethnographic Films Made by the Estonian National Museum (1961–1989) Liivo Niglas, Eva Toulouze

Reconstructing the Past and the Present: the Ethnographic Films Made by the Estonian National Museum (1961–1989) Liivo Niglas, Eva Toulouze To cite this version: Liivo Niglas, Eva Toulouze. Reconstructing the Past and the Present: the Ethnographic Films Made by the Estonian National Museum (1961–1989): Reconstruire le passé et le présent: les films ethno- graphiques réalisés par le Musée national estonien (1961–1989). Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics, University of Tartu, Estonian National Museum and Estonian Literary Museum., 2010, 4 (2), pp.79-96. hal-01276198 HAL Id: hal-01276198 https://hal-inalco.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01276198 Submitted on 19 Feb 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. RECOnstruCtinG THE PAst AND THE Present: THE ETHNOGR APHIC Films MADE BY THE EstOniAN NAtiONAL Museum (1961–1989) LIIVO NIGLAS MA, Researcher Department of Ethnology Institute for Cultural Research and Fine Arts University of Tartu Ülikooli 18, 50090, Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] EVA TOULOUZE PhD Hab., Associate Professor Department of Central and Eastern Europe Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales (INALCO) 2, rue de Lille, 75343 Paris, France e-mail: [email protected] ABstrACT This article* analyses the films made by the Estonian National Museum in the 1970s and the 1980s both from the point of view of the filming activity and of the content of these films. -

224 Volli Kalm

VOLLI KALM (10.02.1953–23.12.2017) In memoriam Rector Professor Volli Kalm Volli Kalm was born at Aluste near Vändra on 10 February 1953. He graduated from the Vändra Secondary School in 1971 and from the Geology speciality of the University of Tartu in 1976. He was a doctoral student of the Institute of Geology of the Estonian Academy of Sciences in 1980–1984 and had his post-doctoral studies at the Alberta University in Canada in 1988–1989. He was a lecturer of the University of Tartu since 1986, then a docent and Head of the Institute of Geology and Dean of the Faculty of Biology and Geography. Volli Kalm was elected as professor in 1992 and was the Vice- Rector for Academic Affairs in 1998–2003 and Rector from 2012. On 1 July 2017, Professor Volli Kalm was re-elected for his second term of office as the head of the University of Tartu and remained the rector until his death. His main research orientations were paleoclimate, paleogeography and chronology of continental glaciations, sedimentology, i.e. research into rock weathering and formation of sedimentary rock, geoarcheology. In 2005 he was awarded the Order of Merit of the White Star – 4th Class. Volli Kalm regarded international cooperation and visibility of the university as very important. In 2016 the University of Tartu became a member of the network of research- intensive universities, The Guild, and Volli Kalm was also elected as a member of its board in 2017. In November 2017, Volli Kalm was elected as the Honorary Doctor of the Tbilisi State University. -

Estonian Yiddish and Its Contacts with Coterritorial Languages

DISSERT ATIONES LINGUISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 1 ESTONIAN YIDDISH AND ITS CONTACTS WITH COTERRITORIAL LANGUAGES ANNA VERSCHIK TARTU 2000 DISSERTATIONES LINGUISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS DISSERTATIONES LINGUISTICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 1 ESTONIAN YIDDISH AND ITS CONTACTS WITH COTERRITORIAL LANGUAGES Eesti jidiš ja selle kontaktid Eestis kõneldavate keeltega ANNA VERSCHIK TARTU UNIVERSITY PRESS Department of Estonian and Finno-Ugric Linguistics, Faculty of Philosophy, University o f Tartu, Tartu, Estonia Dissertation is accepted for the commencement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in general linguistics) on December 22, 1999 by the Doctoral Committee of the Department of Estonian and Finno-Ugric Linguistics, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Tartu Supervisor: Prof. Tapani Harviainen (University of Helsinki) Opponents: Professor Neil Jacobs, Ohio State University, USA Dr. Kristiina Ross, assistant director for research, Institute of the Estonian Language, Tallinn Commencement: March 14, 2000 © Anna Verschik, 2000 Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastuse trükikoda Tiigi 78, Tartu 50410 Tellimus nr. 53 ...Yes, Ashkenazi Jews can live without Yiddish but I fail to see what the benefits thereof might be. (May God preserve us from having to live without all the things we could live without). J. Fishman (1985a: 216) [In Estland] gibt es heutzutage unter den Germanisten keinen Forscher, der sich ernst für das Jiddische interesiere, so daß die lokale jiddische Mundart vielleicht verschwinden wird, ohne daß man sie für die Wissen schaftfixiert -

Estonian Academy of Sciences Yearbook 2018 XXIV

Facta non solum verba ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES YEARBOOK FACTS AND FIGURES ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ESTONICAE XXIV (51) 2018 TALLINN 2019 This book was compiled by: Jaak Järv (editor-in-chief) Editorial team: Siiri Jakobson, Ebe Pilt, Marika Pärn, Tiina Rahkama, Ülle Raud, Ülle Sirk Translator: Kaija Viitpoom Layout: Erje Hakman Photos: Annika Haas p. 30, 31, 48, Reti Kokk p. 12, 41, 42, 45, 46, 47, 49, 52, 53, Janis Salins p. 33. The rest of the photos are from the archive of the Academy. Thanks to all authos for their contributions: Jaak Aaviksoo, Agnes Aljas, Madis Arukask, Villem Aruoja, Toomas Asser, Jüri Engelbrecht, Arvi Hamburg, Sirje Helme, Marin Jänes, Jelena Kallas, Marko Kass, Meelis Kitsing, Mati Koppel, Kerri Kotta, Urmas Kõljalg, Jakob Kübarsepp, Maris Laan, Marju Luts-Sootak, Märt Läänemets, Olga Mazina, Killu Mei, Andres Metspalu, Leo Mõtus, Peeter Müürsepp, Ülo Niine, Jüri Plado, Katre Pärn, Anu Reinart, Kaido Reivelt, Andrus Ristkok, Ave Soeorg, Tarmo Soomere, Külliki Steinberg, Evelin Tamm, Urmas Tartes, Jaana Tõnisson, Marja Unt, Tiit Vaasma, Rein Vaikmäe, Urmas Varblane, Eero Vasar Printed in Priting House Paar ISSN 1406-1503 (printed version) © EESTI TEADUSTE AKADEEMIA ISSN 2674-2446 (web version) CONTENTS FOREWORD ...........................................................................................................................................5 CHRONICLE 2018 ..................................................................................................................................7 MEMBERSHIP -

On Estonian Folk Culture: Pro Et Contra

doi:10.7592/FEJF2014.58.ounapuu ON ESTONIAN FOLK CULTURE: PRO ET CONTRA Piret Õunapuu Abstract: The year 2013 was designated the year of heritage in Estonia, with any kind of intangible and tangible heritage enjoying pride of place. Heritage was written and spoken about and revived in all kinds of ways and manners. The motto of the year was: There is no heritage without heir. Cultural heritage is a comprehensive concept. This article focuses, above all, on indigenous cultural heritage and, more precisely, its tangible (so-called object) part. Was the Estonian peasant, 120 years back, with his gradually increasing self-confidence, proud or ashamed of his archaic household items? Rustic folk culture was highly viable at that time. In many places people still wore folk costumes – if not daily, then at least the older generation used to wear them to church. A great part of Estonians still lived as if in a museum. Actually, this reminded of the old times that people tried to put behind them, and sons were sent to school in town for a better and more civilised future. In the context of this article, the most important agency is peasants’ attitude towards tangible heritage – folk culture in the widest sense of the word. The appendix, Pro et contra, at the end of the article exemplifies this on the basis of different sources. Keywords: creation of national identity, cultural heritage, Estonian National Museum, Estonian Students’ Society, folk costumes, folk culture, Learned Es- tonian Society, material heritage, modernisation, nationalism, social changes HISTORICAL BACKGROUND By the end of the 19th century, the Russification period, several cultural spaces had evolved in the Baltic countries: indigenous, German and Russian. -

Eesti Rahva Muuseumi Algaastate Suurkogumised 11

Eesti Rahva Muuseumi algaastate suurkogumised 11 EESTI RAHVA MUUSEUMI ALGAASTATE SUURKOGUMISED Piret Õunapuu Meie ei waiki, ei wäsi enne, kui iga lapsgi kü- las teab, mis Museum on, ja wiimne kui talu oma muistsused Museumile wälja on andnud. Kristjan Raud1 Sissejuhatus Eesti Rahva Muuseumi esemekogud on tänaseks päevaks kas- vanud umbes 133 000 esemeni2. Alus nendele kogudele pandi kohe pärast muuseumi asutamist, mil esimese kümne aastaga suudeti ko- guda ligi 20 000 eset, kusjuures nendest umbes kaks kolmandikku aastatel 1911–1913. Fenomen, et muuseum, kus tehti põhiliselt vaid ilma rahata tööd isamaa heaks, seadis endale eesmärgiks kogu Eesti- maa kihelkondade kaupa vanavarast tühjaks korjata ja suutis sellele tööle suunata kümneid ja kümneid inimesi, on kogu maailma aja- loos ilmselt ainulaadne. Tulemuseks on mitte ainult rohked, vaid ka väärtuslikud esemekogud, mis jõudsid muuseumisse enne laastavat Esimest maailmasõda. Käesolevas artiklis leiavad käsitlemist ainult esemelise vanavara korjamisega seotud kogumismatkad. Kõik teised muuseumi töösuu- nad nagu näiteks kihutuskõnede pidamine või väljanäituste korral- damine, mis samuti ühel või teisel moel on kogumistööga seotud, jäävad seekord tagaplaanile. Samuti jääb kõrvale „kohalike koguja- te” ja muuseumi usaldusmeeste töö. Seni on enim käsitletud Eesti Rahva Muuseumi varasemat ko- gumistööd eelkõige seoses Kristjan Raua isikuga. Kõige põhjaliku- ma ülevaate sellest annavad Hilja Silla artikkel „Kristjan Raud ja 1 Raud 1911a. 2 31.12.2006 seisuga oli Eesti Rahva Muuseumis esemekogus 132 880 ühikut. 12 Piret Õunapuu vanavara suurkogumine“ (1970) ning Rasmus Kangro-Pooli mono- graafi a Kristjan Raud (1961) peatükk „Kristjan Raud ja Eesti Rah- va Muuseum“. Lehti Viiroja oma raamatus Kristjan Rauast (1981) puudutab samuti ERMi vanavara kogumist seoses Kr. -

Language Attrition and Death: Livonian in Its Terminal Phase

1 Christopher Moseley LANGUAGE ATTRITION AND DEATH: LIVONIAN IN ITS TERMINAL PHASE Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University of London March 1993 ProQuest Number: 10046089 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10046089 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 INTRODUCTION This study of the present state of the Livonian language, a Baltic-Finnic tongue spoken by a few elderly people formerly resident in a dozen fishing villages on the coast of Latvia, consists of four main parts. Part One gives an outline of the known history of the Livonian language, the history of research into it, and of its own relations with its closest geographical neighbour, Latvian, a linguistically unrelated Indo-European language. A state of Latvian/Livonian bilingualism has existed for virtually all of the Livonians' (or Livs') recorded history, and certainly for the past two centuries. Part Two consists of a Descriptive Grammar of the present- day Livonian language as recorded in an extensive corpus provided by one speaker. -

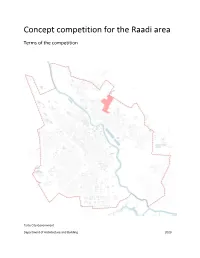

Concept Competition for the Raadi Area

Concept competition for the Raadi area Terms of the competition Tartu City Government Department of Architecture and Building 2020 Table of contents 1. Objective, competition area and contact area of the concept competition .......................................................... 3 2. History .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Detailed plans and architectural plans in effect for the area ................................................................................. 7 4. Streets of the competition area ........................................................................................................................... 11 5. Environment and landscaping .............................................................................................................................. 12 6. Competition task by properties ........................................................................................................................... 13 7. Organisation of the competition .......................................................................................................................... 17 7.1 Organiser of the competition ........................................................................................................................ 17 7.2 Competition format ...................................................................................................................................... -

Downloads/Newsletters/SIEF-Spring-2020.Pdf?Utm Source=Newsletter&Utm Medium=Sendy&Utm Newsletter=SIEF Autumn2019, Last Accessed on 21.09.2020

THE YEARBOOK OF BALKAN AND BALTIC STUDIES VOLUME 3 INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY OF BALKAN AND BALTIC STUDIES THE YEARBOOK OF BALKAN AND BALTIC STUDIES VOLUME 3 TRACKING THE RITUAL YEAR ON THE MOVE IN DIFFERENT CULTURAL SETTINGS AND SYSTEMS OF VALUES editor-in-chief EKATERINA ANASTASOVA guest editors IRINA SEDAKOVA LAURENT SÉBASTIEN FOURNIER ELM SCHOLARLY PRESS VILNIUS-TARTU-SOFIA-RIGA 2020 Editor-in-chief: Ekaterina Anastasova Guest editors: Irina Sedakova, Institute of Slavic Studies, Moscow & Laurent Sébastien Fournier, Aix-Marseille-University, France Editors: Mare Kõiva, Inese Runce, Žilvytis Šaknys Cover: Lina Gergova Layout: Diana Kahre Editorial board: Nevena Škrbić Alempijević (Croatia), Jurji Fikfak (Slovenia), Evangelos Karamanes (Greece), Zoja Karanović (Serbia), Solveiga Krumina-Konkova (Latvia), Andres Kuperjanov (Estonia), Thede Kahl (Germany), Ermis Lafazanovski (North Macedonia), Tatiana Minniyakhmetova (Austria), Alexander Novik (Russia), Rasa Paukštytė-Šaknienė (Lithuania), Irina Sedakova (Russia), Irina Stahl (Romania), Svetoslava Toncheva (Bulgaria), Piret Voolaid (Estonia) Supported by Bulgarian, Lithuanian, Estonian and Latvian Academies of Sciences, Centre of Excellence in Estonian Studies; Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Studies with Ethnographic Museum, Estonian Literary Museum, Lithuanian Institute of History, Institute of Philosophy and Sociology, University of Latvia © 2020 by the authors © International Society of Balkan and Baltic Studies © Estonian Literary Museum ISSN 2613-7844 (printed) ISSN 2613-7852 (pdf) -

Kirjanduslinn Tartu Kaart

Emajõe 29. Kirjandusega seotud paigad Sündmused ja projektid Raamatukogud Raamatupoed 33. 1. Tartu Kirjanduse Maja (Vanemuise 19): Kirjandusfestival Prima Vista: 25. Tartu Oskar Lutsu nimelise Tartu Lõunakeskuse Apollo Kirjanduslinna keskus, kus tegutsevad Eesti mai alguses üle terve linna Kroonuaia sild linnaraamatukogu keskkogu Ringtee 75 Kirjanike Liidu Tartu osakond, Eesti Kirjanduse Kompanii 3/5 E–P 10–21 Rahvusvaheline interdistsiplinaarne festival Oa E–R 9–20, L 10–16 [email protected] Selts, kirjastus Ilmamaa, ajakiri Värske Rõhk, 11. raamatupood Utoopia ning kultuuribaar Arhiiv; „Hullunud Tartu“: igal aastal novembris [email protected] tel 633 6020 (E–R 9–17) Herne tel 736 1380 Narva mnt. 2. Kohvik Werner (Ülikooli 11): üks Eesti vanemaid Luuleprõmmude sari TarSlämm: septembrist 34. Tartu Kaubamaja Apollo kohvikuid, millest kujunes töötegemis- ja ajaveetmis- aprillini kord kuus neljapäeviti kultuuribaaris Arhiiv 26. Linnaraamatukogu Annelinna harukogu Riia 1 paik paljudele Eesti haritlastele, teiste seas luuletaja Kaunase pst 23 E–L 9–21, P 10–19 Vene kirjanduse ja kultuuri nädal: sügiseti E–R 9–20, L 10–16 [email protected] Artur Alliksaarele. On tegevuspaigaks ka Madis Kõivu Vabaduse sild näidendis "Lõputu kohvijoomine"; Tartu linnaraamatukogus tel 746 1040 tel 633 6020 (E-R 9–17) Botaanikaaed Kroonuaia Kirjanduslikud teisipäevad: sügisest kevadeni 27. Linnaraamatukogu Karlova-Ropka harukogu 35. Tasku Keskuse Rahva Raamat 3. Ülikooli kohvik (Ülikooli 20): Tartu spontaanse Mäe kirjanduselu keskus 1960. ja 1970. aastatel. Tartu Kirjanduse Majas Tehase 16 Turu 2 Sissekäigu ees asuv mälestuskivi tähistab Eesti E–R 10–19, L 10–16 E–L 10–21, P 10–18 vanima, 1631 rajatud trükikoja asukohta; Tartu Linnaraamatukogu kirjanduskohvik: [email protected] [email protected] iga kuu viimasel neljapäeval tel 730 8473 tel 671 3659 Kloostri 4.