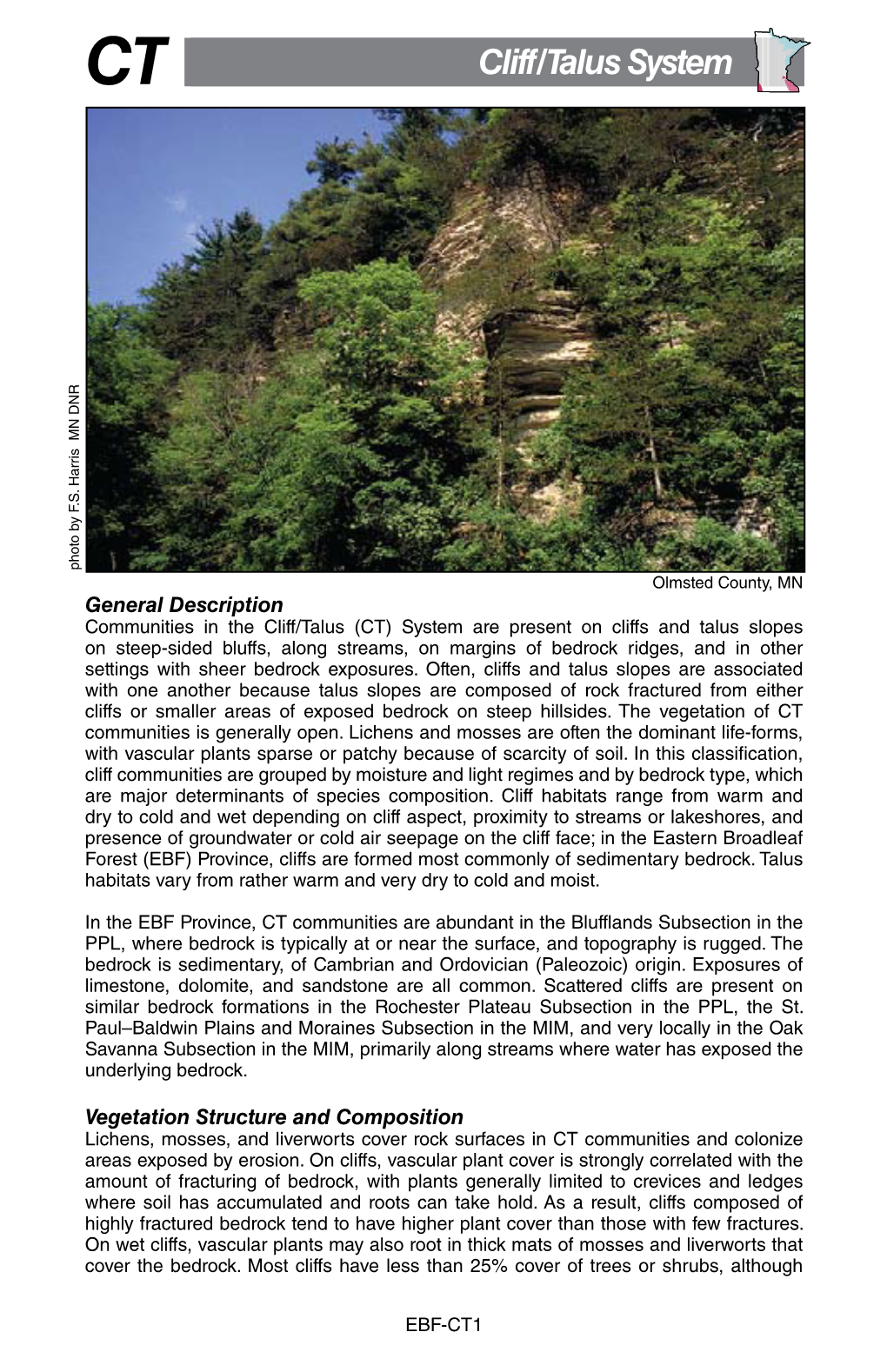

Eastern Broadleaf Forest Province, Cliff/Talus System Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward a Resolution of Campanulid Phylogeny, with Special Reference to the Placement of Dipsacales

TAXON 57 (1) • February 2008: 53–65 Winkworth & al. • Campanulid phylogeny MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS Toward a resolution of Campanulid phylogeny, with special reference to the placement of Dipsacales Richard C. Winkworth1,2, Johannes Lundberg3 & Michael J. Donoghue4 1 Departamento de Botânica, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, Caixa Postal 11461–CEP 05422-970, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. [email protected] (author for correspondence) 2 Current address: School of Biology, Chemistry, and Environmental Sciences, University of the South Pacific, Private Bag, Laucala Campus, Suva, Fiji 3 Department of Phanerogamic Botany, The Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, 104 05 Stockholm, Sweden 4 Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology and Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, P.O. Box 208106, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8106, U.S.A. Broad-scale phylogenetic analyses of the angiosperms and of the Asteridae have failed to confidently resolve relationships among the major lineages of the campanulid Asteridae (i.e., the euasterid II of APG II, 2003). To address this problem we assembled presently available sequences for a core set of 50 taxa, representing the diver- sity of the four largest lineages (Apiales, Aquifoliales, Asterales, Dipsacales) as well as the smaller “unplaced” groups (e.g., Bruniaceae, Paracryphiaceae, Columelliaceae). We constructed four data matrices for phylogenetic analysis: a chloroplast coding matrix (atpB, matK, ndhF, rbcL), a chloroplast non-coding matrix (rps16 intron, trnT-F region, trnV-atpE IGS), a combined chloroplast dataset (all seven chloroplast regions), and a combined genome matrix (seven chloroplast regions plus 18S and 26S rDNA). Bayesian analyses of these datasets using mixed substitution models produced often well-resolved and supported trees. -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Chapter Vii Table of Contents

CHAPTER VII TABLE OF CONTENTS VII. APPENDICES AND REFERENCES CITED........................................................................1 Appendix 1: Description of Vegetation Databases......................................................................1 Appendix 2: Suggested Stocking Levels......................................................................................8 Appendix 3: Known Plants of the Desolation Watershed.........................................................15 Literature Cited............................................................................................................................25 CHAPTER VII - APPENDICES & REFERENCES - DESOLATION ECOSYSTEM ANALYSIS i VII. APPENDICES AND REFERENCES CITED Appendix 1: Description of Vegetation Databases Vegetation data for the Desolation ecosystem analysis was stored in three different databases. This document serves as a data dictionary for the existing vegetation, historical vegetation, and potential natural vegetation databases, as described below: • Interpretation of aerial photography acquired in 1995, 1996, and 1997 was used to characterize existing (current) conditions. The 1996 and 1997 photography was obtained after cessation of the Bull and Summit wildfires in order to characterize post-fire conditions. The database name is: 97veg. • Interpretation of late-1930s and early-1940s photography was used to characterize historical conditions. The database name is: 39veg. • The potential natural vegetation was determined for each polygon in the analysis -

Phylogeny and Phylogenetic Taxonomy of Dipsacales, with Special Reference to Sinadoxa and Tetradoxa (Adoxaceae)

PHYLOGENY AND PHYLOGENETIC TAXONOMY OF DIPSACALES, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO SINADOXA AND TETRADOXA (ADOXACEAE) MICHAEL J. DONOGHUE,1 TORSTEN ERIKSSON,2 PATRICK A. REEVES,3 AND RICHARD G. OLMSTEAD 3 Abstract. To further clarify phylogenetic relationships within Dipsacales,we analyzed new and previously pub- lished rbcL sequences, alone and in combination with morphological data. We also examined relationships within Adoxaceae using rbcL and nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences. We conclude from these analyses that Dipsacales comprise two major lineages:Adoxaceae and Caprifoliaceae (sensu Judd et al.,1994), which both contain elements of traditional Caprifoliaceae.Within Adoxaceae, the following relation- ships are strongly supported: (Viburnum (Sambucus (Sinadoxa (Tetradoxa, Adoxa)))). Combined analyses of C ap ri foliaceae yield the fo l l ow i n g : ( C ap ri folieae (Diervilleae (Linnaeeae (Morinaceae (Dipsacaceae (Triplostegia,Valerianaceae)))))). On the basis of these results we provide phylogenetic definitions for the names of several major clades. Within Adoxaceae, Adoxina refers to the clade including Sinadoxa, Tetradoxa, and Adoxa.This lineage is marked by herbaceous habit, reduction in the number of perianth parts,nectaries of mul- ticellular hairs on the perianth,and bifid stamens. The clade including Morinaceae,Valerianaceae, Triplostegia, and Dipsacaceae is here named Valerina. Probable synapomorphies include herbaceousness,presence of an epi- calyx (lost or modified in Valerianaceae), reduced endosperm,and distinctive chemistry, including production of monoterpenoids. The clade containing Valerina plus Linnaeeae we name Linnina. This lineage is distinguished by reduction to four (or fewer) stamens, by abortion of two of the three carpels,and possibly by supernumerary inflorescences bracts. Keywords: Adoxaceae, Caprifoliaceae, Dipsacales, ITS, morphological characters, phylogeny, phylogenetic taxonomy, phylogenetic nomenclature, rbcL, Sinadoxa, Tetradoxa. -

Mountain Plants of Northeastern Utah

MOUNTAIN PLANTS OF NORTHEASTERN UTAH Original booklet and drawings by Berniece A. Andersen and Arthur H. Holmgren Revised May 1996 HG 506 FOREWORD In the original printing, the purpose of this manual was to serve as a guide for students, amateur botanists and anyone interested in the wildflowers of a rather limited geographic area. The intent was to depict and describe over 400 common, conspicuous or beautiful species. In this revision we have tried to maintain the intent and integrity of the original. Scientific names have been updated in accordance with changes in taxonomic thought since the time of the first printing. Some changes have been incorporated in order to make the manual more user-friendly for the beginner. The species are now organized primarily by floral color. We hope that these changes serve to enhance the enjoyment and usefulness of this long-popular manual. We would also like to thank Larry A. Rupp, Extension Horticulture Specialist, for critical review of the draft and for the cover photo. Linda Allen, Assistant Curator, Intermountain Herbarium Donna H. Falkenborg, Extension Editor Utah State University Extension is an affirmative action/equal employment opportunity employer and educational organization. We offer our programs to persons regardless of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age or disability. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Robert L. Gilliland, Vice-President and Director, Cooperative Extension -

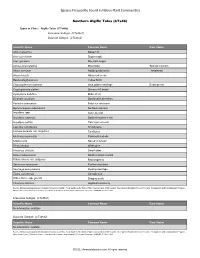

Algific Talus (Cts46)

Species Frequently Found in Native Plant Communities Southern Algific Talus (CTs46) Types in Class: Algific Talus (CTs46a) Limestone Subtype (CTs46a1) Dolomite Subtype (CTs46a2) Scientific Name Column1 Common Name Rare Status Abies balsamea Balsam fir Acer saccharum Sugar maple Acer spicatum Mountain maple Adoxa moschatellina Moschatel Special Concern Allium cernuum Nodding wild onion Threatened Arabis hirsuta Hairy rock cress Betula alleghaniensis Yellow birch Chrysosplenium iowense Iowa golden saxifrage Endangered Cryptogramma stelleri Slender cliff brake Cystopteris bulbifera Bulblet fern Dicentra cucullaria Dutchman's breeches Enemion biternatum False rue anemone Gymnocarpium robertianum Northern oak fern Impatiens spp. touch-me-not Impatiens capensis Spotted touch-me-not Impatiens pallida Pale touch-me-not Laportea canadensis Wood nettle Linnaea borealis var. longiflora Twinflower Mertensia paniculata Panicled bluebells Mitella nuda Naked miterwort Pinus strobus White pine Rhamnus alnifolia Dwarf alder Ribes hudsonianum Northern black currant Rubus idaeus var. strigosus Red raspberry Sambucus racemosa Red-berried elder Saxifraga pensylvanica Swamp saxifrage Taxus canadensis Canada yew Urtica dioica ssp. gracilis Stinging nettle Viburnum trilobum Highbush cranberry Source: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (2005). Field Guide to the Native Plant Communities of Minnesota: The Eastern Broadleaf Forest Province. Ecological Land Classification Program, Minnesota County Biological Survey, and Natural Heritage and Nongame Research Program. MNDNR St. Paul, MN. Limestone Subtype (CTs46a1) Scientific Name Column1 Common Name Rare Status No information available Dolomite Subtype (CTs46a2) Scientific Name Column1 Common Name Rare Status No information available Source: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (2005). Field Guide to the Native Plant Communities of Minnesota: The Eastern Broadleaf Forest Province. Ecological Land Classification Program, Minnesota County Biological Survey, and Natural Heritage and Nongame Research Program. -

Complete Iowa Plant Species List

!PLANTCO FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT TECHNIQUE: IOWA DATABASE This list has been modified from it's origional version which can be found on the following website: http://www.public.iastate.edu/~herbarium/Cofcons.xls IA CofC SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME PHYSIOGNOMY W Wet 9 Abies balsamea Balsam fir TREE FACW * ABUTILON THEOPHRASTI Buttonweed A-FORB 4 FACU- 4 Acalypha gracilens Slender three-seeded mercury A-FORB 5 UPL 3 Acalypha ostryifolia Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 5 UPL 6 Acalypha rhomboidea Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 3 FACU 0 Acalypha virginica Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 3 FACU * ACER GINNALA Amur maple TREE 5 UPL 0 Acer negundo Box elder TREE -2 FACW- 5 Acer nigrum Black maple TREE 5 UPL * Acer rubrum Red maple TREE 0 FAC 1 Acer saccharinum Silver maple TREE -3 FACW 5 Acer saccharum Sugar maple TREE 3 FACU 10 Acer spicatum Mountain maple TREE FACU* 0 Achillea millefolium lanulosa Western yarrow P-FORB 3 FACU 10 Aconitum noveboracense Northern wild monkshood P-FORB 8 Acorus calamus Sweetflag P-FORB -5 OBL 7 Actaea pachypoda White baneberry P-FORB 5 UPL 7 Actaea rubra Red baneberry P-FORB 5 UPL 7 Adiantum pedatum Northern maidenhair fern FERN 1 FAC- * ADLUMIA FUNGOSA Allegheny vine B-FORB 5 UPL 10 Adoxa moschatellina Moschatel P-FORB 0 FAC * AEGILOPS CYLINDRICA Goat grass A-GRASS 5 UPL 4 Aesculus glabra Ohio buckeye TREE -1 FAC+ * AESCULUS HIPPOCASTANUM Horse chestnut TREE 5 UPL 10 Agalinis aspera Rough false foxglove A-FORB 5 UPL 10 Agalinis gattingeri Round-stemmed false foxglove A-FORB 5 UPL 8 Agalinis paupercula False foxglove -

Phylogeny and Phylogenetic Nomenclature of the Campanulidae Based on an Expanded Sample of Genes and Taxa

Systematic Botany (2010), 35(2): pp. 425–441 © Copyright 2010 by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists Phylogeny and Phylogenetic Nomenclature of the Campanulidae based on an Expanded Sample of Genes and Taxa David C. Tank 1,2,3 and Michael J. Donoghue 1 1 Peabody Museum of Natural History & Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, P. O. Box 208106, New Haven, Connecticut 06520 U. S. A. 2 Department of Forest Resources & Stillinger Herbarium, College of Natural Resources, University of Idaho, P. O. Box 441133, Moscow, Idaho 83844-1133 U. S. A. 3 Author for correspondence ( [email protected] ) Communicating Editor: Javier Francisco-Ortega Abstract— Previous attempts to resolve relationships among the primary lineages of Campanulidae (e.g. Apiales, Asterales, Dipsacales) have mostly been unconvincing, and the placement of a number of smaller groups (e.g. Bruniaceae, Columelliaceae, Escalloniaceae) remains uncertain. Here we build on a recent analysis of an incomplete data set that was assembled from the literature for a set of 50 campanulid taxa. To this data set we first added newly generated DNA sequence data for the same set of genes and taxa. Second, we sequenced three additional cpDNA coding regions (ca. 8,000 bp) for the same set of 50 campanulid taxa. Finally, we assembled the most comprehensive sample of cam- panulid diversity to date, including ca. 17,000 bp of cpDNA for 122 campanulid taxa and five outgroups. Simply filling in missing data in the 50-taxon data set (rendering it 94% complete) resulted in a topology that was similar to earlier studies, but with little additional resolution or confidence. -

Flora of Vascular Plants of the Seili Island and Its Surroundings (SW Finland)

Biodiv. Res. Conserv. 53: 33-65, 2019 BRC www.brc.amu.edu.pl DOI 10.2478/biorc-2019-0003 Submitted 20.03.2018, Accepted 10.01.2019 Flora of vascular plants of the Seili island and its surroundings (SW Finland) Andrzej Brzeg1, Wojciech Szwed2 & Maria Wojterska1* 1Department of Plant Ecology and Environmental Protection, Faculty of Biology, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Umultowska 89, 61-614 Poznań, Poland 2Department of Forest Botany, Faculty of Forestry, Poznań University of Life Sciences, Wojska Polskiego 71D, 60-625 Poznań, Poland * corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7774-1419) Abstract. The paper shows the results of floristic investigations of 12 islands and several skerries of the inner part of SW Finnish archipelago, situated within a square of 11.56 km2. The research comprised all vascular plants – growing spontaneously and cultivated, and the results were compared to the present flora of a square 10 × 10 km from the Atlas of Vascular Plants of Finland, in which the studied area is nested. The total flora counted 611 species, among them, 535 growing spontaneously or escapees from cultivation, and 76 exclusively in cultivation. The results showed that the flora of Seili and adjacent islands was almost as rich in species as that recorded in the square 10 × 10 km. This study contributed 74 new species to this square. The hitherto published analyses from this area did not focus on origin (geographic-historical groups), socioecological groups, life forms and on the degree of threat of recorded species. Spontaneous flora of the studied area constituted about 44% of the whole flora of Regio aboënsis. -

Distribution of Ribes, an Alternate Host of White Pine Blister Rust, in Colorado and Wyoming1 Holly S

Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 135(3), 2008, pp. 423–437 Distribution of Ribes, an alternate host of white pine blister rust, in Colorado and Wyoming1 Holly S. J. Kearns2,3 and William R. Jacobi4 Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523-1177 Kelly S. Burns USDA Forest Service, Forest Health Management, Golden, CO 80401-4720 Brian W. Geils USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Flagstaff, AZ 86001 KEARNS, H. S. J., W. R. JACOBI (Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523-1177), K. S. BURNS (USDA Forest Service, Forest Health Management, Golden, CO 80401-4720), AND B. W. GEILS (USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Flagstaff, AZ 86001). Distribution of Ribes, an alternate host of white pine blister rust, in Colorado and Wyoming. J. Torrey Bot. Soc. 135: 423–437. 2008.—Ribes (currants and gooseberries) are alternate hosts for Cronartium ribicola, the invasive fungus that causes blister rust of white pines (Pinus, subgenus Strobus) in the Rocky Mountain region of Colorado and Wyoming. The location, species, and density of Ribes can affect the spread and impact of this potentially serious forest disease. We assessed the distribution and density of Ribes growing near white pine stands for 15 study areas in Colorado and Wyoming with 1258 survey plots of two types, an intensive white pine/Ribes survey and an extensive Ribes survey. Species present, total numbers of stems and bushes, average number of stems per bush, and average stem length were recorded. Various Ribes species were present in all study areas across a range of elevations. -

Plant Propagation Protocol for Ribes Hudsonianum ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production Spring 2009

Plant Propagation Protocol for Ribes Hudsonianum ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production Spring 2009 Figure 1: Ribes Hudsonianum Richardson (Courtesy of Emmet J. Judziewicz) (Robert W. Freckmann Herbarium) TAXONOMY Family Names Family Scientific Grossulariaceae Name: Family Common Currant family Name: Scientific Names Genus: Ribes Species: hudsonianum Species Authority: Richardson Variety: Variety Ribes hudsonianum Richardson var. hudsonianum – Hudson Bay currant Variety Ribes hudsonianum Richardson var. petiolare (Douglas) Jancz. – western black currant (United States Department of Agriculture, 2009) Sub‐species: Cultivar: Authority for Variety/Sub‐ species: Common Synonym(s) Northern black currant (include full Canadian black currant (Robert W. Freckmann Herbarium) scientific names (e.g., Elymus glaucus Buckley), including variety or subspecies information) Common Name(s): Hudson's Bay Currant, Northern Black Currant Species Code (as per RIHU USDA Plants database): GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical range (distribution maps for North America and Washington state) Figure 2: Ribes Hudsonianum. Distribution in North America. Shaded – present, white – absent (Courtesy (United States Department of Agriculture, 2009) NORTHERN AMERICA Subarctic America: Canada ‐ Northwest Territory, Yukon Territory; United States ‐ Alaska Eastern Canada: Canada ‐ Ontario, Quebec [w.] Western Canada: Canada ‐ Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Saskatchewan Northeastern U.S.A.: United States ‐ Michigan [n.] North‐Central U.S.A.: United States ‐ Iowa [n.e.], Minnesota -

Adoxaceae 1.3.3.8.1.A

190 1.3.3.8.1. Adoxaceae 1.3.3.8.1.a. Características. ¾ Porte: hierbas delicadas perennes con olor a almizcle (Adoxa) o bien arbustos a pequeños árboles (Viburnum y Sambucus). ¾ Hojas: opuestas, simples o compuestas, pinnadas o trifoliadas, decusadas, con estípulas caedizas o sin estas, venación palmada a pinnadas, con pelos glandulares. ¾ Flores: gamopétalas, perfectas, generalmente en cimas plurifloras, a veces capitadas, entomófilas. ¾ Perianto: cáliz gamosépalo, en Adoxa con un hipanto cortamente prolongado, casi siempre 4-5 dentado. Corola generalmente 5, raro 3-4-mera, actinomorfas o zigomorfas, rotada o acampanada. ¾ Androceo: 3-5 estambres fijos al tubo corolino, anteras introrsas rara vez extrorsas (Sambucus). ¾ Gineceo: ovario ínfero o semiínfero, 2-5 carpelos y lóculos, con 1 óvulo péndulos; estilo filiforme corto; estigma lobulado. ¾ Fruto: drupa, baya o rara vez cápsula. ¾ Semilla: a menudo ruminada, endospermada; embrión pequeño. Sambucus australis c. Flor pistilada b. Flor estaminada a. Rama d. Corte longitudinal de flor pistilada g. corte longitudinal de semilla f. vista subapical de fruto Extraído de Bacigalupo, 1974 (Fl. Entre Ríos). e. Corte de transversal de ovario Diversidad Vegetal- Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales y Agrimensura (UNNE) CORE EUDICOTILEDÓNEAS- Asterídeas-Euasterídeas II: Dipsacales: Adoxaceae 191 1.3.3.8.1.b. Biología Floral. La polinización la llevan a cabo insectos (Izco, 1998). 1.3.3.8.1.c. Distribución y hábitat En la circunscripción actual la familia se encuentra más representada en las regiones templadas del hemisferio Norte (América y Asia), hallándose ausente en el Sahara, África tropical y del sur (Heywood, 1985). En el hemisferio sur se las encuentra principalmente en montañas tropicales (Stevens, 2008).