Gaelic and Scottish Naming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaelic Scotland – a Postcolonial Site? in Search of a Meaningful Theoretical Framework to Assess the Dynamics of Contemporary Scottish Gaelic Verse

eSharp Issue 6:1 Identity and Marginality Gaelic Scotland – A Postcolonial Site? In Search of a Meaningful Theoretical Framework to Assess the Dynamics of Contemporary Scottish Gaelic Verse Corinna Krause (University of Edinburgh) The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw what is known today as the Highland Clearances, which was in effect the forced migration of a large proportion of the population of the Scottish Highlands due to intensified sheep farming in the name of a more effective economic land use (Devine, 1999, pp.176-78). For the Gaelic speech community this meant ‘the removal of its heartland’ (MacKinnon, 1974, p.47). MacKinnon argues that ‘effectively this was to reorientate the linguistic geography of Scotland in reducing the Gaelic areas to the very fringes of northern and western coastal areas and to the Hebrides’ (1974, p.47). Yet, it was not economic exploitation alone which influenced the existence of the Gaelic population in a most profound way. There was also an active interference with language use through the eradication of Gaelic from the sphere of education as manifested in a series of Education Acts from 1872 onwards. Such education policy ensured the integration of the Gaelic speech community into English-language Britain (MacKinnon, 1974, pp.54-74). Gaelic Scotland therefore had its share of experiencing what in postcolonial literary studies is identified as the ‘two indivisible foundations of imperial authority - knowledge and power’ (Ashcroft, Griffiths and Tiffin, 1995, p.1; referring to Said, -

Gaelic Barbarity and Scottish Identity in the Later Middle Ages

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten MacGregor, Martin (2009) Gaelic barbarity and Scottish identity in the later Middle Ages. In: Broun, Dauvit and MacGregor, Martin(eds.) Mìorun mòr nan Gall, 'The great ill-will of the Lowlander'? Lowland perceptions of the Highlands, medieval and modern. Centre for Scottish and Celtic Studies, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, pp. 7-48. ISBN 978085261820X Copyright © 2009 University of Glasgow A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/91508/ Deposited on: 24 February 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 Gaelic Barbarity and Scottish Identity in the Later Middle Ages MARTIN MACGREGOR One point of reasonably clear consensus among Scottish historians during the twentieth century was that a ‘Highland/Lowland divide’ came into being in the second half of the fourteenth century. The terminus post quem and lynchpin of their evidence was the following passage from the beginning of Book II chapter 9 in John of Fordun’s Chronica Gentis Scotorum, which they dated variously from the 1360s to the 1390s:1 The character of the Scots however varies according to the difference in language. For they have two languages, namely the Scottish language (lingua Scotica) and the Teutonic language (lingua Theutonica). -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Etymology of the Principal Gaelic National Names

^^t^Jf/-^ '^^ OUTLINES GAELIC ETYMOLOGY BY THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, Stirwng f ETYMOLOGY OF THK PRINCIPAL GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES |'( I WHICH IS ADDED A DISQUISITION ON PTOLEMY'S GEOGRAPHY OF SCOTLAND B V THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, STIRLING 1911 PRINTKD AT THE " NORTHERN OHRONIOLB " OFFICE, INYBRNESS PREFACE The following Etymology of the Principal Gaelic ISTational Names, Personal Names, and Surnames was originally, and still is, part of the Gaelic EtymologicaJ Dictionary by the late Dr MacBain. The Disquisition on Ptolemy's Geography of Scotland first appeared in the Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, and, later, as a pamphlet. The Publisher feels sure that the issue of these Treatises in their present foim will confer a boon on those who cannot have access to them as originally published. They contain a great deal of information on subjects which have for long years interested Gaelic students and the Gaelic public, although they have not always properly understood them. Indeed, hereto- fore they have been much obscured by fanciful fallacies, which Dr MacBain's study and exposition will go a long way to dispel. ETYMOLOGY OF THE PRINCIPAI, GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES ; NATIONAL NAMES Albion, Great Britain in the Greek writers, Gr. "AXfSiov, AX^iotv, Ptolemy's AXovlwv, Lat. Albion (Pliny), G. Alba, g. Albainn, * Scotland, Ir., E. Ir. Alba, Alban, W. Alban : Albion- (Stokes), " " white-land ; Lat. albus, white ; Gr. dA</)os, white leprosy, white (Hes.) ; 0. H. G. albiz, swan. -

Reference Guides for Registering Students with Non English Names

Getting It Right Reference Guides for Registering Students With Non-English Names Jason Greenberg Motamedi, Ph.D. Zafreen Jaffery, Ed.D. Allyson Hagen Education Northwest June 2016 U.S. Department of Education John B. King Jr., Secretary Institute of Education Sciences Ruth Neild, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Delegated Duties of the Director National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance Joy Lesnick, Acting Commissioner Amy Johnson, Action Editor OK-Choon Park, Project Officer REL 2016-158 The National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE) conducts unbiased large-scale evaluations of education programs and practices supported by federal funds; provides research-based technical assistance to educators and policymakers; and supports the synthesis and the widespread dissemination of the results of research and evaluation throughout the United States. JUNE 2016 This project has been funded at least in part with federal funds from the U.S. Department of Education under contract number ED‐IES‐12‐C‐0003. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Education nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. REL Northwest, operated by Education Northwest, partners with practitioners and policymakers to strengthen data and research use. As one of 10 federally funded regional educational laboratories, we conduct research studies, provide training and technical assistance, and disseminate information. Our work focuses on regional challenges such as turning around low-performing schools, improving college and career readiness, and promoting equitable and excellent outcomes for all students. -

Dialectal Diversity in Contemporary Gaelic: Perceptions, Discourses and Responses Wilson Mcleod

Dialectal diversity in contemporary Gaelic: perceptions, discourses and responses Wilson McLeod 1 Introduction This essay will address some aspects of language change in contemporary Gaelic and their relationship to the simultaneous workings of language shift and language revitalisation. I focus in particular on the issue of how dialects and dialectal diversity in Gaelic are perceived, depicted and discussed in contemporary discourse. Compared to many minoritised languages, notably Irish, dialectal diversity has generally not been a matter of significant controversy in relation to Gaelic in Scotland. In part this is because Gaelic has, or at least is depicted as having, relatively little dialectal variation, in part because the language did undergo a degree of grammatical and orthographic standardisation in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, with the Gaelic of the Bible serving to provide a supra-dialectal high register (e.g. Meek 1990). In recent decades, as Gaelic has achieved greater institutionalisation in Scotland, notably in the education system, issues of dialectal diversity have not been prioritised or problematised to any significant extent by policy-makers. Nevertheless, in recent years there has been some evidence of increasing concern about the issue of diversity within Gaelic, particularly as language shift has diminished the range of spoken dialects and institutionalisation in broadcasting and education has brought about a degree of levelling and convergence in the language. In this process, some commentators perceive Gaelic as losing its distinctiveness, its richness and especially its flavour or blas. These responses reflect varying ideological perspectives, sometimes implicating issues of perceived authenticity and ownership, issues which become heightened as Gaelic is acquired by increasing numbers of non-traditional speakers with no real link to any dialect area. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

Candy Flossing the Celtic Fringe Gwyn Illtyd Lewis Near the Tudor Court, Or by the Barrier of Language

Universities & Left Review Summer 1957 Vol.1 No. 2 The Uses of Literacy Candy Flossing the Celtic Fringe Gwyn Illtyd Lewis near the Tudor court, or by the barrier of language. The Much of Mr. Hoggart's thesis about working-class gentry gradually ceased to be the natural patrons of Welsh culture has a regional stamp which, he would poetry, music and letters and became an alien class whose probably be the first to admit, cannot of necessity be taken special distinguishing marks, apart from their rapacity as beyond the geographical limits of his field of study, much landlords, was their English tongue and official status. The less universalized to represent the workers' reactions in the peasantry became a class enjoying something like colonial whole of Britain. status with an unofficial language and an unofficial or Welsh social conditions have variously been described as "native" culture with no definitive institutions to sustain classless or as totally working-class by observers outside it, with few civil rights except what the common law Wales who take what is known of the English provincial (administered in a strange tongue) secured them, and no i class structure as the norm. The clue to this, and there is privileges. some truth in it, can be found as far back as the Renais- sance when Wales lost what remained of its indigenous institutions and was assimilated to England, Henry Tudor's Peasant into worker Act of Union, 1536, being the political instrument. The The 19th Century in Wales saw the victory of the peasant ] social results were that London became the new focus and class (Gwerin) which by this time had become class- anglicisation the aim of the gentry. -

Barristers on Panel

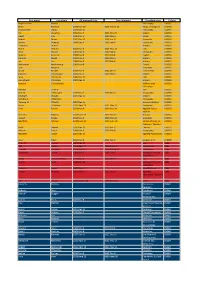

st Report Run Date: 21 Jun 2019 BARRISTERS ON PANEL The below list contains information on the number of payments* and the total amount paid to On Panel barristers for the period 1/07/18 – 31/12/18 Amount Number Amount Number Amount Number Amount Number Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of (€) Payments (€) Payments (€) Payments (€) Payments Buckley, Declan 417,945 52 McGrath, Imogen 43,604 15 Binchy, Michael 11,132 8 Fitzpatrick, Andrew 3,094 6 Egan, Emily 394,952 24 Boughton, David 43,480 86 Farrelly, Aoife 10,908 13 Fitzgerald, William 2,653 11 Hanratty, Patrick 385,932 11 Fleck, Kieran 43,142 7 Delaney, Michael Patrick 10,701 2 MacMahon, Noel A. 2,583 1 Halpin, Conor 337,833 26 Gayer, Sasha Louise 39,452 4 Lydon, Eileen 10,578 2 Roberts, Conor 2,030 3 O'Braonain, Luan 231,215 17 Ramsey, Michael 37,023 1 Hand, Derry 10,376 8 Cheatle, John 1,845 1 Kavanagh, James M. 187,198 6 Fahey, Grainne 36,678 73 Scully, Lorraine 9,696 6 Maher, Jeremy 1,538 2 Foley, Brian 181,914 20 McGuinness, Donal 29,223 5 Hogan, John 9,545 7 Keleher, Daniel 1,162 1 Woulfe, Donnchadh 179,160 9 Lowe, Robert 28,226 2 Walsh, Aidan 8,979 1 Hewson, Dermot G. 1,119 1 McCrann, Oonah 159,623 18 Barrington, Eileen 27,596 2 Kilfeather, Jonathan 8,642 4 Keane, Deirdre 1,076 4 McCullough, Eoin 143,268 14 White, Rory 27,032 14 Fleming, David 8,107 2 Danaher, Gerard 954 2 Corcoran, Sarah 139,707 104 Farren, Georgina 25,227 5 Tennyson, Lauren 7,679 3 Cullinane, Padraig J. -

Name Standards User Guide

User Guide Contents SEVIS Name Standards 1 SEVIS Name Fields 2 SEVIS Name Standards Tied to Standards for Machine-readable Passport 3 Applying the New Name Standards 3 Preparing for the New Name Standards 4 Appendix 1: Machine-readable Passport Name Standards 5 Understanding the Machine-readable Passport 5 Name Standards in the Visual Inspection Zone (VIZ) 5 Name Standards in the Machine-readable Zone (MRZ) 6 Transliteration of Names 7 Appendix 2: Comparison of Names in Standard Passports 10 Appendix 3: Exceptional Situations 12 Missing Passport MRZ 12 SEVIS Name Order 12 Unclear Name Order 14 Names-Related Resources 15 Bibliography 15 Document Revision History 15 SEVP will implement a set of standards for all nonimmigrant names entered into SEVIS. This user guide describes the new standards and their relationship to names written in passports. SEVIS Name Standards Name standards help SEVIS users: Comply with the standards governing machine-readable passports. Convert foreign names into standardized formats. Get better results when searching for names in government systems. Improve the accuracy of name matching with other government systems. Prevent the unacceptable entry of characters found in some names. SEVIS Name Standards User Guide SEVIS Name Fields SEVIS name fields will be long enough to capture the full name. Use the information entered in the Machine-Readable Zone (MRZ) of a passport as a guide when entering names in SEVIS. Field Names Standards Surname/Primary Name Surname or the primary identifier as shown in the MRZ -

History of the Mackenzies Alexander Mackenzie

History Of The Mackenzies Alexander Mackenzie THE HISTORY OF THE MACKENZIES. ORIGIN. THE CLAN MACKENZIE at one time formed one of the most powerful families in the Highlands. It is still one of the most numerous and influential, and justly claims a very ancient descent. But there has always been a difference of opinion regarding its original progenitor. It has long been maintained and generally accepted that the Mackenzies are descended from an Irishman named Colin or Cailean Fitzgerald, who is alleged but not proved to have been descended from a certain Otho, who accompanied William the Conqueror to England, fought with that warrior at the battle of Hastings, and was by him created Baron and Castellan of Windsor for his services on that occasion. THE REPUTED FITZGERALD DESCENT. According to the supporters of the Fitzgerald-Irish origin of the clan, Otho had a son Fitz-Otho, who is on record as his father's successor as Castellan of Windsor in 1078. Fitz-Otho is said to have had three sons. Gerald, the eldest, under the name of Fitz- Walter, is said to have married, in 1112, Nesta, daughter of a Prince of South Wales, by whom he also had three sons. Fitz-Walter's eldest son, Maurice, succeeded his father, and accompanied Richard Strongbow to Ireland in 1170. He was afterwards created Baron of Wicklow and Naas Offelim of the territory of the Macleans for distinguished services rendered in the subjugation of that country, by Henry II., who on his return to England in 1172 left Maurice in the joint Government. -

First Name Last Name GB Approval Date Date Informed Discipline/Area

First Name Last Name GB Approval Date Date Informed Discipline/area College Roger Garrett Barden Philosophy CACSSS Brian Bocking 2015 Nov 15 2016 March 14 Study of Religions CACSSS Desmond M Clarke 2007 Dec 11 Philosophy CACSSS Pat Coughlan 2013 Nov 5 2013 Nov 15 English CACSSS David Cox 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 Music CACSSS Robert Devoy 2011 Dec 13 2012 Jan 11 Geograhy CACSSS Francis Douglas 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 Education CACSSS Thomas J Dunne History CACSSS Maire Herbert 2013 Nov 5 2013 Nov 15 Irish CACSSS Aine Hyland 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 Education CACSSS Colbert Kearney 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 English CACSSS Dermot Keogh 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 History CACSSS Joe Lee 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 History CACSSS Mathew M MacNamara 2005 Nov 8 French CACSSS John Maguire Sociology CACSSS Grace Neville 2012 Nov 6 2012 Dec 6 French/T&L CACSSS Eamonn O Carragain 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 English CACSSS Sean O Coileain 2006 Dec 12 Irish CACSSS Donnchadh O Corrain 2007 Dec 11 History CACSSS Gearóid Ó Crualaoich Folklore and CACSSS Ethnology Padraig O Riain irish CACSSS Patrick O'Flanagan 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 Geography CACSSS Elisabeth Okasha 2007 Dec 11 English CACSSS Brendan E O'Mahony Philosophy CACSSS Terence W O'Reilly 2007 Dec 11 Hispanic Studies CACSSS Denis O'Sullivan 2011 April 19 2011 May 11 Education CACSSS Fred Powell 2014 Nov 4 2014 Nov 24 Applied Social CACSSS Studies Geoffrey Roberts 2017 June 13 2017 Dec 01 History CACSSS Joseph Ruane 2014 Nov 4 2014 Nov 24 Sociology CACSSS Manfred Schewe 2019 June 11 2019 June 18 School of Lang, Lit, CACSSS