Rethinking US-Cuba Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slum Clearance in Havana in an Age of Revolution, 1930-65

SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 by Jesse Lewis Horst Bachelor of Arts, St. Olaf College, 2006 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jesse Horst It was defended on July 28, 2016 and approved by Scott Morgenstern, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Edward Muller, Professor, Department of History Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History Co-Chair: George Reid Andrews, Distinguished Professor, Department of History Co-Chair: Alejandro de la Fuente, Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin American History and Economics, Department of History, Harvard University ii Copyright © by Jesse Horst 2016 iii SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 Jesse Horst, M.A., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This dissertation examines the relationship between poor, informally housed communities and the state in Havana, Cuba, from 1930 to 1965, before and after the first socialist revolution in the Western Hemisphere. It challenges the notion of a “great divide” between Republic and Revolution by tracing contentious interactions between technocrats, politicians, and financial elites on one hand, and mobilized, mostly-Afro-descended tenants and shantytown residents on the other hand. The dynamics of housing inequality in Havana not only reflected existing socio- racial hierarchies but also produced and reconfigured them in ways that have not been systematically researched. -

Canada, the Us and Cuba

CANADA, THE US AND CUBA CANADA, THE US AND CUBA HELMS-BURTON AND ITS AFTERMATH Edited by Heather N. Nicol Centre for International Relations, Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada 1999 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: Canada, the US and Cuba : Helms-Burton and its aftermath (Martello papers, ISSN 1183-3661 ; 21) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-88911-884-1 1. United States. Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity (LIBERTAD) Act of 1996. 2. Canada – Foreign relations – Cuba. 3. Cuba – Foreign relations – Canada. 4. Canada – Foreign relations – United States. 5. United States – Foreign relations – Canada. 6. United States – Foreign relations – Cuba. 7. Cuba – Foreign relations – United States. I. Nicol, Heather N. (Heather Nora), 1953- . II. Queen’s University (Kingston, Ont.). Centre for International Relations. III. Series. FC602.C335 1999 327.71 C99-932101-3 F1034.2.C318 1999 © Copyright 1999 The Martello Papers The Queen’s University Centre for International Relations (QCIR) is pleased to present the twenty-first in its series of security studies, the Martello Papers. Taking their name from the distinctive towers built during the nineteenth century to de- fend Kingston, Ontario, these papers cover a wide range of topics and issues rele- vant to contemporary international strategic relations. This volume presents a collection of insightful essays on the often uneasy but always interesting United States-Cuba-Canada triangle. Seemingly a relic of the Cold War, it is a topic that, as editor Heather Nicol observes, “is always with us,” and indeed is likely to be of greater concern as the post-Cold War era enters its second decade. -

126613844.23.Pdf

-Raj? Sds.m.s? PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME LIX PAPERS RELATING TO THE SCOTS IN POLAND November 1915 I v PAPERS RELATING TO THE SCOTS IN POLAND 1576-1798 Edited with an Introduction by A. FRANCIS STEUART ADVOCATE EDINBURGH Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1915 PREFACE It is very necessary to present to the members of the Scottish History Society, in an apologetic vein, the disastrously chequered history of this very much belated book. The original intention of the Council was to issue Papers relating to the Scots in Poland, a collection made by and in part edited by Miss Beatrice Baskerville, and, as it was expected that this volume would be ready in 1907-1908, its title was accordingly placed among the Society’s publications for that year. Many and serious delays occurred, however : some were caused by the awkward climatic conditions of Poland, which render the transcribing of original documents by copyists almost impossible for many months of each year, other delays were caused by the difficulty of printing exactly (as was originally intended) the Manuscripts sent in Polish or Polish Latin transcriptions by not too accurate archivists. Losses of letters in the post, and changes in the secretariat of the Society further protracted matters. Then, as could not have been anticipated, the Balkan War arose, which distracted Miss Baskerville’s attention from her book to a more active Slavonic field. Lastly, the Polish and German literati engaged later to translate portions of this unlucky work were suddenly called off to fight in the great International War of 1914, and their places were only filled eventually by gracious volunteers, who bridged over by their kindness and labour yet another difficulty which could not have been foreseen. -

Trading with the Enemy: Opening the Door to U.S. Investment in Cuba

ARTICLES TRADING WITH THE ENEMY: OPENING THE DOOR TO U.S. INVESTMENT IN CUBA KEVIN J. FANDL* ABSTRACT U.S. economic sanctions on Cuba have been in place for nearly seven deca- des. The stated intent of those sanctionsÐto restore democracy and freedom to CubaÐis still used as a justi®cation for maintaining harsh restrictions, despite the fact that the Castro regime remains in power with widespread Cuban public support. Starving the Cuban people of economic opportunities under the shadow of sanctions has signi®cantly limited entrepreneurship and economic development on the island, despite a highly educated and motivated popula- tion. The would-be political reformers and leaders on the island emigrate, thanks to generous U.S. immigration policies toward Cubans, leaving behind the Castro regime and its ardent supporters. Real change on the island will come only if the United States allows Cuba to restart its economic engine and reengage with global markets. Though not a guarantee of political reform, eco- nomic development is correlated with demand for political change, giving the economic development approach more potential than failed economic sanctions. In this short paper, I argue that Cuba has survived in spite of the U.S. eco- nomic embargo and that dismantling the embargo in favor of open trade poli- cies would improve the likelihood of Cuba becoming a market-friendly communist country like China. I present the avenues available today for trade with Cuba under the shadow of the economic embargo, and I argue that real po- litical change will require a leap of faith by the United States through removal of the embargo and support for Cuba's economic development. -

The Cuban American National Foundation and Its Role As an Ethnic Interest Group

The Cuban American National Foundation and Its Role as an Ethnic Interest Group Author: Margaret Katherine Henn Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/568 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2008 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Introduction Since the 1960s, Cuban Americans have made social, economic, and political progress far beyond that of most immigrant groups that have come to the United States in the past fifty years. I will argue that the Cuban American National Foundation (CANF) was very influential in helping the Cuban Americans achieve much of this progress. It is, however, important to note that Cubans had some distinct advantages from the beginning, in terms of wealth and education. These advantages helped this ethnic interest group to grow quickly and become powerful. Since its inception in the early 1980s, the CANF has continually been able to shape government policy on almost all issues related to Cuba. Until at least the end of the Cold War, the CANF and the Cuban American population presented a united front in that their main goal was to present a hard line towards Castro and defeat him; they sought any government assistance they could get to achieve this goal, from policy changes to funding for different dissident activities. In more recent years, Cubans have begun to differ in their opinions of the best policy towards Cuba. I will argue that this change along with other changes will decrease the effectiveness of the CANF. -

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009

16 April 2009 OpenȱSourceȱCenter Report Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009 Raul Castro has overhauled the leadership of top government bodies, especially those dealing with the economy, since he formally succeeded his brother Fidel as president of the Councils of State and Ministers on 24 February 2008. Since then, almost all of the Council of Ministers vice presidents have been replaced, and more than half of all current ministers have been appointed. The changes have been relatively low-key, but the recent ousting of two prominent figures generated a rare public acknowledgement of official misconduct. Fidel Castro retains the position of Communist Party first secretary, and the party leadership has undergone less turnover. This may change, however, as the Sixth Party Congress is scheduled to be held at the end of this year. Cuba's top military leadership also has experienced significant turnover since Raul -- the former defense minister -- became president. Names and photos of key officials are provided in the graphic below; the accompanying text gives details of the changes since February 2008 and current listings of government and party officeholders. To view an enlarged, printable version of the chart, double-click on the following icon (.pdf): This OSC product is based exclusively on the content and behavior of selected media and has not been coordinated with other US Government components. This report is based on OSC's review of official Cuban websites, including those of the Cuban Government (www.cubagob.cu), the Communist Party (www.pcc.cu), the National Assembly (www.asanac.gov.cu), and the Constitution (www.cuba.cu/gobierno/cuba.htm). -

Islenos and Malaguenos of Louisiana Part 1

Islenos and Malaguenos of Louisiana Part 1 Louisiana Historical Background 1761 – 1763 1761 – 1763 1761 – 1763 •Spain sides with France in the now expanded Seven Years War •The Treaty of Fontainebleau was a secret agreement of 1762 in which France ceded Louisiana (New France) to Spain. •Spain acquires Louisiana Territory from France 1763 •No troops or officials for several years •The colonists in western Louisiana did not accept the transition, and expelled the first Spanish governor in the Rebellion of 1768. Alejandro O'Reilly suppressed the rebellion and formally raised the Spanish flag in 1769. Antonio de Ulloa Alejandro O'Reilly 1763 – 1770 1763 – 1770 •France’s secret treaty contained provisions to acquire the western Louisiana from Spain in the future. •Spain didn’t really have much interest since there wasn’t any precious metal compared to the rest of the South America and Louisiana was a financial burden to the French for so long. •British obtains all of Florida, including areas north of Lake Pontchartrain, Lake Maurepas and Bayou Manchac. •British built star-shaped sixgun fort, built in 1764, to guard the northern side of Bayou Manchac. •Bayou Manchac was an alternate route to Baton Rouge from the Gulf bypassing French controlled New Orleans. •After Britain acquired eastern Louisiana, by 1770, Spain became weary of the British encroaching upon it’s new territory west of the Mississippi. •Spain needed a way to populate it’s new territory and defend it. •Since Spain was allied with France, and because of the Treaty of Allegiance in 1778, Spain found itself allied with the Americans during their independence. -

The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade

Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 18 January 2017 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PRUSSIAN CRUSADE The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade explores the archaeology and material culture of the Crusade against the Prussian tribes in the thirteenth century, and the subsequent society created by the Teutonic Order that lasted into the six- teenth century. It provides the first synthesis of the material culture of a unique crusading society created in the south-eastern Baltic region over the course of the thirteenth century. It encompasses the full range of archaeological data, from standing buildings through to artefacts and ecofacts, integrated with writ- ten and artistic sources. The work is sub-divided into broadly chronological themes, beginning with a historical outline, exploring the settlements, castles, towns and landscapes of the Teutonic Order’s theocratic state and concluding with the role of the reconstructed and ruined monuments of medieval Prussia in the modern world in the context of modern Polish culture. This is the first work on the archaeology of medieval Prussia in any lan- guage, and is intended as a comprehensive introduction to a period and area of growing interest. This book represents an important contribution to promot- ing international awareness of the cultural heritage of the Baltic region, which has been rapidly increasing over the last few decades. Aleksander Pluskowski is a lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at the University of Reading. Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 -

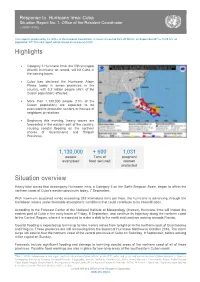

Highlights Situation Overview

Response to Hurricane Irma: Cuba Situation Report No. 1. Office of the Resident Coordinator ( 07/09/ 20176) This report is produced by the Office of the Resident Coordinator. It covers the period from 20:00 hrs. on September 06th to 14:00 hrs. on September 07th.The next report will be issued on or around 08/09. Highlights Category 5 Hurricane Irma, the fifth strongest Atlantic hurricane on record, will hit Cuba in the coming hours. Cuba has declared the Hurricane Alarm Phase today in seven provinces in the country, with 5.2 million people (46% of the Cuban population) affected. More than 1,130,000 people (10% of the Cuban population) are expected to be evacuated to protection centers or houses of neighbors or relatives. Beginning this evening, heavy waves are forecasted in the eastern part of the country, causing coastal flooding on the northern shores of Guantánamo and Holguín Provinces. 1,130,000 + 600 1,031 people Tons of pregnant evacuated food secured women protected Situation overview Heavy tidal waves that accompany Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, began to affect the northern coast of Cuba’s eastern provinces today, 7 September. With maximum sustained winds exceeding 252 kilometers (km) per hour, the hurricane is advancing through the Caribbean waters under favorable atmospheric conditions that could contribute to its intensification. According to the Forecast Center of the National Institute of Meteorology (Insmet), Hurricane Irma will impact the eastern part of Cuba in the early hours of Friday, 8 September, and continue its trajectory along the northern coast to the Central Region, where it is expected to make a shift to the north and continue moving towards Florida. -

Vanguard Economic and Market Outlook 2021: Approaching the Dawn

Vanguard economic and market outlook for 2021: Approaching the dawn Vanguard Research December 2020 ■ While the global economy continues to recover as we head into 2021, the battle between the virus and humanity’s efforts to stanch it continues. Our outlook for the global economy hinges critically on health outcomes. The recovery’s path is likely to prove uneven and varied across industries and countries, even with an effective vaccine in sight. ■ In China, we see the robust recovery extending in 2021 with growth of 9%. Elsewhere, we expect growth of 5% in the U.S. and 5% in the euro area, with those economies making meaningful progress toward full employment levels in 2021. In emerging markets, we expect a more uneven and challenging recovery, with growth of 6%. ■ When we peek beyond the long shadow of COVID-19, we see the pandemic irreversibly accelerating trends such as work automation and digitization of economies. However, other more profound setbacks brought about by the lockdowns and recession will ultimately prove temporary. Assuming a reasonable path for health outcomes, the scarring effect of permanent job losses is likely to be limited. ■ Our fair-value stock projections continue to reveal a global equity market that is neither grossly overvalued nor likely to produce outsized returns going forward. This suggests, however, that there may be opportunities to invest broadly around the world and across the value spectrum. Given a lower-for-longer rate outlook, we find it hard to see a material uptick in fixed income returns in the foreseeable future. Lead authors Vanguard Investment Strategy Group Vanguard Global Economics and Capital Markets Outlook Team Joseph Davis, Ph.D., Global Chief Economist Joseph Davis, Ph.D. -

Mecanismos Represivos Del Estado Cubano

46 Mecanismos Represivos del Estado Cubano Repressive Mechanisms Roberto Garcés Marrero of the Cuban State Universidad Iberoamericana, Ciudad de México Resumen El presente trabajo analiza algunos de los mecanismos represivos del estado cubano, a saber: los actos de repudio, la regulación, el descrédito y la difamación, la vigilancia panóptica y el hostigamiento policial. Se estudiaron cinco casos típicos, con ocasión de ello, se ha recurrido a Twitter como plataforma de investigación, complementada por publicaciones cubanas independientes y documentales en YouTube. La metodología utilizada está basada en la participación observante y la investigación onlife. Los mecanismos represivos enumerados no son solo de carácter punitivo, al mismo tiempo, van construyendo a los enemigos, que es una de las causales de la aparente cohesión social actual en Cuba a partir del miedo y la desconfianza mutua que generan en la población. Palabras Claves: Control social, Cuba, derechos humanos. Abstract This paper analyzes some of the repressive mechanisms of the Cuban state: repudiation rally, regulation, discrediting and defamation, panoptic surveillance and police harassment. For this, taking Twitter as a research platform, complemented by independent Cuban publications and documentaries on YouTube, five typical cases were studied. The methodology is based on observant participation and onlife research. These repressive mechanisms are not only punitive in nature, but they build up enemies, actually being one of the causes of the apparent current social cohesion in Cuba based on fear and mutual distrust that they generate in the population. Keywords: Social control, Cuba, human rights. Introducción fue el pretexto perfecto para mantener un estado de La Revolución cubana devino en una suerte de excepción permanente que legitimaba la toma de de- utopía latinoamericana antiimperialista, mitologi- cisiones radicales.