Endgame in Burma 349

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rail Infrastructure Development Plan and Planning for International Railway Connectivity in Myanmar

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT AND COMMUNICATIONS MYANMA RAILWAYS Expert Group Meeting on the Use of New Technologies for Facilitation of International Railway Transport 9-12 December, 2019 Rail Infrastructure Development Plan and Planning for International Railway Connectivity in Myanmar Ba Myint Managing Director Myanma Railways Ministry of Transport and Communications MYANMAR Contents . Brief Introduction on situation of Transport Infrastructure in Myanmar . Formulation of National Transport Master Plan . Preparation for the National Logistics Master Plan Study (MYL‐Plan) . Status of Myanma Railways and Current Rail Infrastructure Development Projects . Planning for International Railway Connectivity in Myanmar 2 Brief Introduction on situation of Transport Infrastructure in Myanmar Myanma’s Profile . Population – 54.283 Million(March,2018) India . Area ‐676,578 Km² China . Coastal Line ‐ 2800 km . Road Length ‐ approximately 150,000 km . Railways Route Length ‐ 6110.5 Km . GDP per Capita – 1285 USD in 2018 Current Status Lao . Myanmar’s Transport system lags behind ASEAN . 60% of highways and rail lines in poor condition Thailand . 20 million People without basic road access . $45‐60 Billion investments needs (2016‐ 2030) Reduce transport costs by 30% Raise GDP by 13% Provide basic road access to 10 million people and save People’s lives on the roads. 4 Notable Geographical Feature of MYANMAR India China Bangaladesh Lao Thailand . As land ‐ bridge between South Asia and Southeast Asia as well as with China . Steep and long mountain ranges hamper the development of transport links with neighbors. 5 Notable Geographical Feature China 1,340 Mil. India 1,210 mil. Situated at a cross‐road of 3 large economic centers. -

TRENDS in MANDALAY Photo Credits

Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN MANDALAY Photo credits Paul van Hoof Mithulina Chatterjee Myanmar Survey Research The views expressed in this publication are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of UNDP. Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN MANDALAY UNDP MYANMAR Table of Contents Acknowledgements II Acronyms III Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 11 2. Methodology 14 2.1 Objectives 15 2.2 Research tools 15 3. Introduction to Mandalay region and participating townships 18 3.1 Socio-economic context 20 3.2 Demographics 22 3.3 Historical context 23 3.4 Governance institutions 26 3.5 Introduction to the three townships participating in the mapping 33 4. Governance at the frontline: Participation in planning, responsiveness for local service provision and accountability 38 4.1 Recent developments in Mandalay region from a citizen’s perspective 39 4.1.1 Citizens views on improvements in their village tract or ward 39 4.1.2 Citizens views on challenges in their village tract or ward 40 4.1.3 Perceptions on safety and security in Mandalay Region 43 4.2 Development planning and citizen participation 46 4.2.1 Planning, implementation and monitoring of development fund projects 48 4.2.2 Participation of citizens in decision-making regarding the utilisation of the development funds 52 4.3 Access to services 58 4.3.1 Basic healthcare service 62 4.3.2 Primary education 74 4.3.3 Drinking water 83 4.4 Information, transparency and accountability 94 4.4.1 Aspects of institutional and social accountability 95 4.4.2 Transparency and access to information 102 4.4.3 Civil society’s role in enhancing transparency and accountability 106 5. -

AROUND MANDALAY You Cansnoopaboutpottery Factories

© Lonely Planet Publications 276 Around Mandalay What puts Mandalay on most travellers’ maps looms outside its doors – former capitals with battered stupas and palace walls lost in palm-rimmed rice fields where locals scoot by in slow-moving horse carts. Most of it is easy day-trip potential. In Amarapura, for-hire rowboats drift by a three-quarter-mile teak-pole bridge used by hundreds of monks and fishers carrying their day’s catch home. At the canal-made island capital of Inwa (Ava), a flatbed ferry then a horse cart leads visitors to a handful of ancient sites surrounded by village life. In Mingun – a boat ride up the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) from Mandalay – steps lead up a battered stupa more massive than any other…and yet only a AROUND MANDALAY third finished. At one of Myanmar’s most religious destinations, Sagaing’s temple-studded hills offer room to explore, space to meditate and views of the Ayeyarwady. Further out of town, northwest of Mandalay in Sagaing District, are a couple of towns – real ones, the kind where wide-eyed locals sometimes slip into approving laughter at your mere presence – that require overnight stays. Four hours west of Mandalay, Monywa is near a carnivalesque pagoda and hundreds of cave temples carved from a buddha-shaped moun- tain; further east, Shwebo is further off the travelways, a stupa-filled town where Myanmar’s last dynasty kicked off; nearby is Kyaukmyaung, a riverside town devoted to pottery, where you can snoop about pottery factories. HIGHLIGHTS Join the monk parade crossing the world’s longest -

MANDALAY REGION, PYIN OO LWIN DISTRICT Pyin Oo Lwin Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census MANDALAY REGION, PYIN OO LWIN DISTRICT Pyin Oo Lwin Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Mandalay Region, Pyin Oo Lwin District Pyin Oo Lwin Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No.48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1 : Map of Mandalay Region, showing the townships Pyin Oo Lwin Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 255,508 2 Population males 128,027 (50.1%) Population females 127,481 (49.9%) Percentage of urban population 62.1% Area (Km2) 1,978.1 3 Population density (per Km2) 129.2 persons Median age 26.8 years Number of wards 21 Number of village tracts 37 Number of private households 53,382 Percentage of female headed households 22.6% Mean household size 4.3 persons 4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 24.7% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 70.7% Elderly population (65+ years) 4.6% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 41.3 Child dependency ratio 34.9 Old dependency ratio 6.4 Ageing index 18.5 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 100 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 95.4% Male 97.5% Female 93.4% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 5,334 2.1 Walking 2,190 0.9 Seeing 2,633 1.0 Hearing 1,334 0.5 Remembering 1,454 0.6 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per -

Mandalay Region Census Report Volume 3 – L

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Mandalay Region Census Report Volume 3 – l Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Mandalay Region Report Census Report Volume 3 – I For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 2: Map of Mandalay Region, Districts and Townships ii Census Report Volume 3–I (Mandalay) Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is now my hope that the main results both Union and each of the State and Region reports will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national and sub-national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and officers at the State/Region, District and Township levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

The Myanmar-Thailand Corridor 6 the Myanmar-Malaysia Corridor 16 the Myanmar-Korea Corridor 22 Migration Corridors Without Labor Attachés 25

Online Appendixes Public Disclosure Authorized Labor Mobility As a Jobs Strategy for Myanmar STRENGTHENING ACTIVE LABOR MARKET POLICIES TO ENHANCE THE BENEFITS OF MOBILITY Public Disclosure Authorized Mauro Testaverde Harry Moroz Public Disclosure Authorized Puja Dutta Public Disclosure Authorized Contents Appendix 1 Labor Exchange Offices in Myanmar 1 Appendix 2 Forms used to collect information at Labor Exchange Offices 3 Appendix 3 Registering jobseekers and vacancies at Labor Exchange Offices 5 Appendix 4 The migration process in Myanmar 6 The Myanmar-Thailand corridor 6 The Myanmar-Malaysia corridor 16 The Myanmar-Korea corridor 22 Migration corridors without labor attachés 25 Appendix 5 Obtaining an Overseas Worker Identification Card (OWIC) 29 Appendix 6 Obtaining a passport 30 Cover Photo: Somrerk Witthayanant/ Shutterstock Appendix 1 Labor Exchange Offices in Myanmar State/Region Name State/Region Name Yangon No (1) LEO Tanintharyi Dawei Township Office Yangon No (2/3) LEO Tanintharyi Myeik Township Office Yangon No (3) LEO Tanintharyi Kawthoung Township Office Yangon No (4) LEO Magway Magwe Township Office Yangon No (5) LEO Magway Minbu District Office Yangon No (6/11/12) LEO Magway Pakokku District Office Yangon No (7) LEO Magway Chauk Township Office Yangon No (8/9) LEO Magway Yenangyaung Township Office Yangon No (10) LEO Magway Aunglan Township Office Yangon Mingalardon Township Office Sagaing Sagaing District Office Yangon Shwe Pyi Thar Township Sagaing Monywa District Office Yangon Hlaing Thar Yar Township Sagaing Shwe -

Massacre in Central Burma: Muslim Students Terrorized and Killed in Meiktila Contents

Physicians for Massacre In Central Burma: Human Rights Muslim Students Terrorized and Killed in Meiktila May 2013 Burmese boys stand near a destroyed home on April 5, 2013, in Meiktila, Burma. Photo: Paula Bronstein/Getty Images physiciansforhumanrights.org About Physicians for Human Rights For more than 25 years, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR)’s use of science and medicine has been on the cutting edge of human rights work. 1986 2003 Led investigations of torture in Warned US policymakers on health Chile, gaining freedom for heroic and human rights conditions prior doctors there to and during the invasion of Iraq 1988 2004 First to document the Iraqi use Documented genocide and sexual of chemical weapons on Kurds, violence in Darfur in support of providing evidence for prosecution international prosecutions of war criminals 2010 1996 Investigated the epidemic of Exhumed mass graves in the violence spread by Burma’s Balkans for International Tribunals, military junta and sounded the alarm about refugee camps in Bosnia and 2012 Kosovo Trained doctors, lawyers, police, and judges in the Democratic 1996 Republic of the Congo, Kenya, and Provided evidence of genocide for Syria on the proper collection of the International Criminal Tribunal evidence in sexual violence cases for Rwanda 2013 1997 Won first prize in the Tech Shared the Nobel Peace Prize for Challenge for Atrocity Prevention the International Campaign to Ban with MediCapt, our mobile app Landmines that documents evidence of torture and sexual violence 2 Arrow Street 1156 15th Street, NW physiciansforhumanrights.org Suite 301 Suite 1001 Cambridge, MA Washington, DC ©2013 Physicians for Human Rights. -

Laboratory Aspects in Vpds Surveillance and Outbreak Investigation

Laboratory Aspect of VPD Surveillance and Outbreak Investigation Dr Ommar Swe Tin Consultant Microbiologist In-charge National Measles & Rubella Lab, Arbovirus section, National Influenza Centre NHL Fever with Rash Surveillance Measles and Rubella Achieving elimination of measles and control of rubella/CRS by 2020 – Regional Strategic Plan Key Strategies: 1. Immunization 2. Surveillance 3. Laboratory network 4. Support & Linkages Network of Regional surveillance officers (RSO) and Laboratories NSC Office 16 RSOs Office Subnational Measles & Rubella Lab, Subnational JE lab National Measles/Rubella Lab (NHL, Yangon) • Surveillance began in 2003 • From 2005 onwards, case-based diagnosis was done • Measles virus isolation was done since 2006 • PCR since 2016 Sub-National Measles/Rubella Lab (PHL, Mandalay) • Training 29.8.16 to 2.9.16 • Testing since Nov 2016 • Accredited in Oct 2017 Measles Serology Data Measles Measles IgM Measles IgM Measles IgM Test Done Positive Negative Equivocal 2011 1766 1245 452 69 2012 1420 1182 193 45 2013 328 110 212 6 2014 282 24 254 4 2015 244 6 235 3 2016 531 181 334 16 2017 1589 1023 503 62 Rubella Serology Data Rubella Test Rubella IgM Rubella IgM Rubella IgM Done Positive Negative Equivocal 2011 425 96 308 21 2012 195 20 166 9 2013 211 23 185 3 2014 257 29 224 4 2015 243 34 196 13 2016 535 12 511 12 2017 965 8 948 9 Measles Genotypes circulating in Myanmar 1. Isolation in VERO h SLAM cell line 2. Positive culture shows syncytia formation 3. Isolated MeV or sample by PCR 4. Positive PCR product is sent to RRL for sequencing 5. -

Response to Rfp Tier 4 (Public Narrative) Services in the Energy Infrastructure Sector

RESPONSE TO RFP TIER 4 (PUBLIC NARRATIVE) SERVICES IN THE ENERGY INFRASTRUCTURE SECTOR PROJECT DEVELOPMENT SOLAR MANUFACTURING ASSET MANAGEMENT (O&M): Solar, Wind, Hydro, Waste-to-Power, Energy Efficiency and Energy Storage A portfolio company of ACO Investment Group www.convalt.com Executive Summary Convalt Energy, Inc. (Convalt), is a U.S.-based global independent power producer owned by the investment firm ACO Investment Group (“ACO”). Convalt is focused on developing, owning, and operating renewable energy assets, especially solar, wind, hydro, waste to power, and geothermal. Convalt is submitting an Expression of Interest for the Tier 4 RFP dated May 12, 2021 to NYSERDA. Working via the Jefferson County Industrial Development Agency we have been provided the following site for the development and operation of the solar manufacturing plant which will produce all the panels needed for our projects. [ redacted ] The location of the site is on Route 12F in the town of Hounsfield near Watertown International Airport, New York. The site is [ REDACTED ] hectares in total. The map below gives the location of the site with the coordinates of the corners of the site underneath the map. DIAGRAM REDACTED 2 Impact of COVID on Proposer and Project Development Convalt Energy, Inc. (Convalt) is a global operator of renewable power and we had impact in our Indian operations but contingency measures helped us weather the storm. There are significant delays in construction, transportation but this should get better in the next year. Our project development while delayed by 4 months is proceeding without interruptions. Proposer Experience Convalt Energy, Inc. (Convalt) is a global operator of renewable power and has extensive experience in project development and now setting up the 2nd largest manufacturing plant in the United States to produce solar panels in Watertown, NY. -

University of Mandalay Mandalay, Myanmar March 2007 Tint Lwin

University of Mandalay ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN PAKHAN GYI DURING THE MONARCHICAL DAYS Tint Lwin Mandalay, Myanmar March 2007 ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN PAKHAN GYI DURING THE MONARCHICAL DAYS University of Mandalay ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN PAKHAN GYI DURING THE MONARCHICAL DAYS A Dissertation submitted to University of Mandalay in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History Department of History Tint Lwin 4 Ph.D/Hist.-3 Mandalay, Myanmar March 2007 University of Mandalay ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN PAKHAN GYI DURING THE MONARCHICAL DAYS By Tint Lwin, B.A(Hist:), M.A. 4 Ph.D./Hist.-3 (2006-07) This Dissertation is submitted to the Board of Examiners In History, University of Mandalay in Candidature For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved External Examiner, Referee Supervisor Member Member Co-Supervisor Chairperson Abstract In writing this dissertation on the "Art and Architecture in Pakhangyi during the monarchical days", every conceivable aspect has been covered, and the dissertation is divided into four chapters. In writing the First Chapter, the artifacts and implements of Neolithic age period, the religious edifices and wall paintings are mainly used as evidences to show the development of Pakhangyi region as one of the main centres of Myanmar civilization other than Bagan and other places of cultural interest. The First Chapter asserts the historical and cultural legitimacy of the Pakhangyi region by presenting its visible facets of successive periods starting from the stone age: stone implements, how the very term Pakhangyi emerge, the oldest villages, the massive city wall, how the city was rebuilt five times, the quality of bricks used and the pattern of brick bonding, water supply system, agriculture and the region’s inhabitants. -

Tota Fatality Lists (Last Updated on 23 March 2021

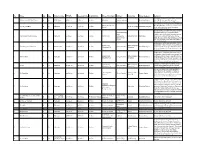

Date of No. Name Sex Age Father's name Deceased Date Organization Place of Incidents Address Township States/Regions Remarks Incident 75 Street, In another incident, 32 years old Ko Na Pwar 1 Na Pwar (aka) Ko Nyi Nyi Oo M 32 U Hla Ngwe 8-Feb-21 8-Feb-21 Civilian Mandalay Between 37 & 38 Mandalay Region (a.k.a Ko Ko Oo), was died after a car Street intentionally hit him at night in Mandalay. On 15 February evening, 18-years old Maung Myeik, Tanintharyi Nay Nay Win Htet was beaten on his head to 2 Nay Nay Win Htet M 18 Unknown 15-Feb-21 15-Feb-21 Civilian Myeik Township Tanintharyi Region Region, death while guarding a ward security in Myeik, Tanintharyi Region, On February 9, peaceful anti-coup protests in Hlaykhwintaung, Naypyitaw were suppressed using water Lower cannon, rubber bullets and live ammunition 3 Mya Thwate Thwate Khaing F 19 Unknown 9-Feb-21 19-Feb-21 civilian NayPyi Taw Paunglaung Zayyarthiri Tsp Naypyidaw resulting in four injured persons. Among Hydro Power them, Ma Mya Thawe Thawe Khaing, 21-years Project old, on 19 February later died from gunshot wounds to the head. In Mandalay, a shipyard raid turned violent on Saturday when security forces opened fire Kannar road, Maha Aungmye 4 Thet Naing Win @ Min Min M 37 U Maung San 20-Feb-21 20-Feb-21 Civilian near 41st street Mandalay Region on demonstrators trying to stop the arrest of Mandalay City Township workers taking part in the growing anti-coup movement. In Mandalay, a shipyard raid turned violent on Saturday when security forces opened fire Kannar road, Maha Aungmye on demonstrators trying to stop the arrest of 5 Wai Yan Htun M 16 Unknown 20-Feb-21 20-Feb-21 Civilian near 41st street Mandalay Region Mandalay City Township workers taking part in the growing anti-coup movement. -

From Kunming to Mandalay: the New “Burma Road”

AsieAsie VVisionsisions 2525 From Kunming to Mandalay: The New “Burma Road” Developments along the Sino-Myanmar border since 1988 Hélène Le Bail Abel Tournier March 2010 Centre Asie Ifri The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental and a non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the authors alone. ISBN : 978-2-86592-675-6 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2010 IFRI IFRI-BRUXELLES 27 RUE DE LA PROCESSION RUE MARIE-THÉRÈSE, 21 75740 PARIS CEDEX 15 - FRANCE 1000 - BRUXELLES, BELGIQUE PH. : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 PH. : +32 (2) 238 51 10 FAX: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 FAX: +32 (2) 238 51 15 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] WEBSITE: Ifri.org China Program, Centre Asie/Ifri The Ifri China Program’s objectives are: . To organize regular exchanges with Chinese elites and enhance mutual trust through the organization of 4 annual seminars in Paris or Brussels around Chinese participants.