September 2014 Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psalm 89-93: Christ Our New King June 6, 2021 Message: Take a Few

Psalm 89-93: Christ Our New King June 6, 2021 Message: Take a few moments to review the message notes from Sunday. What was your main takeaway from this message? Digging Deeper: Small Group Discussion 1.) What stood out to you? 2.) (Psalm 89) From the people’s perspective… their reality did not align with all of God’s promises. What happens when your reality fails to align with what you know to be true about God? 3.) (Psalm 90) In verse 12, what do you think it means when Moses says, “Teach us to number our days so that we may gain a heart of wisdom.”? 4.) (Psalm 91) God is our protection in verses 9 and 10, is God’s protection available to everyone? 5.) (Psalm 91:10) Does God’s protection mean Christians are immune from all harm? 6.) Satan quotes verse 11 to Jesus in the wilderness (Luke 4:9-12). The devil would like us to think that God’s promises have failed especially if He lets us suffer. Where does verse 15 say God will be? 7.) When the Israelites were tested in the wilderness they fell for Satan’s temptations. When Jesus was tested by Satan in the wilderness, He resisted temptation. What type of guidance does he model for us? 8.) (Psalm 92) This chapter is titled “A Song for the Sabbath Day.” It was written to be sung in community on the sabbath day. What do verses 1-4 teach us about praising God? 9.) (Psalm 93) This chapter reminds us the Lord reigns over all. -

Malkhuyot Sources Uhrbach.Pdf

אמר הקדוש ברוך הוא ... ואמרו לפני בראש השנה מלכיות זכרונות ושופרות מלכיות כדי שתמליכוני עליכם זכרונות כדי שיעלה זכרוניכם לפני לטובה ובמה בשופר כת' רבי' סעדיה מה שצונו הבורא יתברך לתקוע בשופר בראש השנה יש בזה עשרה ענינים. הענין הראשון מפני שהיום היתה תחלת הבריאה שבו ברא הקב"ה את העולם ומלך עליו וכן עושים המלכים בתחלת מלכותם שתוקעים לפניהם בחצוצרות ובקרנות להודיע ולהשמיע בכל מקום התחלת מלכותם וכן אנו ממליכין עלינו את הבורא ליום זה וכך אמר דוד בחצוצרות וקול שופר הריעו לפני המלך ה'. והטעם שתקנו לומר מראש השנה ועד יום הכפורים המלך במקום האל לפי שמראה מלכותו על בני העולם ששופט אותם בימים אלו אֵ ין מַ זְכִּירִ ין זִכְרוֹנוֹת מַ לְכֻיּוֹת וְ שׁוֹפָ רוֹת שֶׁ ל פֻּרְ עָ נוּת. זִכְ רוֹנוֹת כְּגוֹן )תהילים עח לט( "וַיִּזְכֹּר כִּי בָשָׂ ר הֵמָּ ה" וְ כוּ'. מַ לְכֻיּוֹת כְּגוֹן )יחזקאל כ לג( ה"בְּחֵמָ שְׁ פוּכָה אֶמְ לוְֹך ֲעֵליֶכם". שֹׁוָפרֹות ְכּגֹון )הושע ה ח( "ִתְּקעוּ שֹׁוָפר בַּגִּבְעָ ה" וְ כוּ'. ְוֹלא ִזְכרֹוָן יִחידֲאִפלּוּ ְלטֹוָבה ְכּגֹון )תהילים קו ד( "ָזְכֵרִני ה' ִבְּרצֹון ַעֶמָּך". )נחמיה ה יט( )נחמיה יג לא( "ָזְכָרה ִלּיֱ אֹלַהי ְלטֹוָבה". וִּפְקדֹונֹותֵאיָנן ְכִּזְכרֹונֹות. ְכּגֹון )שמות ג טז( "ָפֹּקד ָפַּקְדִתּיֶאְתֶכם". ְוֵישׁ לֹו ְלַהְזִכּיר ֻפְּרָענוֶּת שׁלֻאמֹּוַת עכּוּ''ם ְכּגֹון )תהילים צט א( "ה' מָ לְָך יִ ְרְגּזַוּ עִמּים". )תהילים קלז ז( "ְזֹכר ה' ִלְבֵניֱ אדֹוםֶאת יֹוְם ירָוּשָׁלִם".)גמרא ראש השנה לב ב( " ַוה'ֱ אֹלִהים ַבּשֹּׁוָפרִ יְתָקע ְוָהַלְך ְבַּסֲערֹות ֵתּיָמן". )דברים ו ד( ְ"שַׁמִעיְשָׂרֵאל ה'ֱ אֹלֵהינוּ ה' ֶאָחד". )דברי ם ד לה( ַ"אָתּה ָהְרֵאָת ָלַדַעת" ְוכ וּ'. )דברים ד לט( "ְוָיַדְעָתּ ַהיֹּום ַוֲהֵשֹׁבָת ֶאל ְלָבֶבָך" ְוכוּ'. ָכּל ָפּסוּקֵ מֵאלּוַּמְלכוּ ת הִוּא עְנָינֹו ַאַף על ִפּיֶשֵׁאין בֹּו ֵזֶכרַמְלכוּת ַוֲהֵרי הוּא ְכּמֹו )שמות טו יח( "ה'ִ יְמלֹוְך ְלעֹוָלם ָוֶעד", )דברים לג ה( "ַוְיִהי ִבֻישׁרוּןֶ מֶלְך" ְוכוּ ': ותמצא באלו השלשה ובכן ובכן ובכן רמז למלכיות זכרונות ושופרו ת כי הראשון הוא ובכן תן פחדך ה' אלקינו וייראוך כל המעשים ויעשו כלם אגודה אחת כנגד מלכיות כי כל זה ענין הממלכה שממליכין אותו. -

Yamim Noraim Flyer 12-Pg 5771

Days of Awe ………….. 5771 Rabbi Linda Holtzman • Rabbi Yael Levy Dina Schlossberg, President • Rabbit Brian Walt, Rabbi Emeritus Gabrielle Kaplan Mayer, Coordinator of Spiritual Life for Children & Youth Rivka Jarosh, Education Director 4101 Freeland Avenue • Philadelphia, PA 19128 Phone: 215-508-0226 • Fax: 215-508-0932 Email: [email protected] • Website: www.mishkan.org DAYS OF AWE 5771 Shalom, Welcome to a year of opportunity at Mishkan Shalom! Our first of many opportunities will be that of starting the year together at services for the Yamim Noraim. It is a pleasure to begin the year as a community, joining old friends and new, praying and learning together. This year, Rabbi Yael Levy will not be with us at the services for the Yamim Noraim. We will miss Rabbi Yael, and hope that her sabbatical time is fulfilling and energizing and that we will learn much from her when she returns to Mishkan Shalom in November. Our services will feel different this year, but the depth and talent of our many members who will participate will add real beauty to them. I am thrilled that joining us to lead the davening will be Sue Hoffman, Rabbi Rebecca Alpert, Cindy Shapiro, Karen Escovitz (Otter), Elliott batTzedek, Wendy Galson, Susan Windle, Andy Stone, Bill Grey, Dan Wolk, several of our teens and many other Mishkan members. As we look ahead to the new year, we pray that 5771 will be filled with abundant blessings for us and for the world. I look forward to celebrating with you. L’shalom, Rabbi Linda Holtzman SECTION 1: LOCATION , VOLUNTEER FORM , FEES AND SERVICE INFORMATION A: WE HAVE • Morning services on the first day of Rosh Hashanah and all services on Yom Kippur will be held at the Haverford School . -

Torah Vayikra: Leviticus 1:1 – 5:26 Haftarah: Isaiah 43:21 – 44:26 B’Rit Chadasha: Hebrews 10:1-23

Introduction to Parsha #24: Vayikra1 READINGS: Torah Vayikra: Leviticus 1:1 – 5:26 Haftarah: Isaiah 43:21 – 44:26 B’rit Chadasha: Hebrews 10:1-23 . and He [the Holy One] called/cried out . [Leviticus 1:1(a)] ___________________________________________________ This Week’s Amidah prayer Focus is the G’vurot, the Prayer of His Powers, Part II Vayikra el-Moshe – i.e. And He [the Holy One] called/cried out for Moshe . vayedaber Adonai elav me'Ohel Mo'ed – and the Holy One spoke to him from within the Tent of Meeting . Leviticus 1:1a. It has begun, Beloved! The glorious era of Imanu-El – i.e. God with us, dwelling in our midst, communing with us, and ruling over us – is underway! Behold, the Tabernacle of God will be with men, and He will be our God, and we will be His People2 . Selah! What Is that Strange and Wonderful Tent-Like Structure that Now Stands at the Epicenter of the Camp of B’nei Yisrael? How Will It Change our Lives? What Does it Portend For the World? The Immaculate Construction project called for by the Holy One’s Great Sinaitic ‘Mish’kan Discourse’3 is now complete. The 'Tabernacle' - the structure that the Hebrew text of Torah calls not only the ‘Mish’kan’ (abode/dwelling place), but also the Mik’dash (receptacle/repository of flowing, pulsing holiness), and the Ohel Moed (Tent of Meeting/Communion/Appointment) - is in place. The moveable, shadow-box edifice the Holy One told Moshe He wanted us to build 1 All rights with respect to this publication are reserved to the author, William G. -

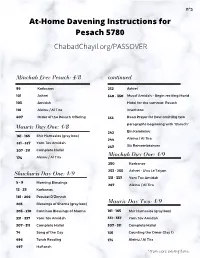

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

The Mishkan at Central Synagogue Pride Shabbat, June 29, 2019 / 26 Sivan 5779

The Mishkan at Central Synagogue Pride Shabbat, June 29, 2019 / 26 Sivan 5779 (142) Opening Song / Oseh Shalom Supplementary Prayers and Songs: Morning Blessings of Gratitude / Birchot HaShachar We Are Loved / Ahavah Rabah (Shir Waking / Modeh Ani Ya’akov) We are loved, loved, loved Gathering / Mah Tovu By unending love (76) Our Bodies / Asher Yatzar An unending love (78) Our Souls / Elohai Neshama Everyday Miracles / Nisim B’Chol Yom Prayer for Healing (Todd Herzog) Learning Torah El Na, R’fa Na Lah, R’fa Na Lanu Songs of Praise / P’sukei D’Zimrah (98) Psalm 145 / Ashrei--Va’Anachnu Dear God of our ancestors Help us renew our faith (100) Psalm 150 / Hallelujah Grant us a perfect healing The Shema and its Blessings Bring peace to all our days (108) Call to Prayer / Bar’chu Restore our strength of body (110) The Wonder of Creation / Yotzeir Or Help clarify our minds (112) The Loving Gift of Torah / Ahavah Rabbah Refresh our tired spirits (114) Proclaiming God’s Oneness / Shema Rejuvenate our light (116) Love for God’s Teaching / V’ahavta (122) Redemption / Mi Chamocha—Tzur Yisrael Vahasheivota / V’neemar (Shir Ya’akov) Standing Prayer / Tefillah / Amidah Vahasheivota el levav’cha (124) Open our Mouths / Adonai Sefatai Tiftach ki Adonai, Hu HaElohim … V’neemar, v’haya Adonai Avot (126) God of Our Ancestors / L’melech al kol HaAretz (128) Life-Giving and Powerful God / G’vurot Bayom Hahu, yih’yeh Adonai echad (130) Sanctifying God’s Name / Kedushah Ush’mo echad Sanctifying Shabbat / Yis’m’chu or V’Shamru We Give Thanks / Modim Anachnu Lach Prayer for Peace / Sim Shalom May Our Prayers Be Heard / Yih’yu L’ratzon (142) Prayer for Peace / Oseh Shalom Torah Service (248) Words of the Prophets / Haftarah Proclaiming God’s Greatness / Vahasheivota (OOS) Mourners’ Prayer / Kaddish Yatom (294) Closing song / Oseh Shalom (142) . -

Psalm 100 | Said Together

Morning Prayer: Rite II Third Sunday of Lent March 7, 2021 | 9:30am If we say we have no sin, we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us, but if we confess our sins, God, who is faithful and just, will forgive our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness. 1 John 1:8,9 BCP p. 76 Confession of Sin Officiant: Let us confess our sins against God and our neighbor. (Silence) All Most merciful God, we confess that we have sinned against you in thought, word, and deed, by what we have done, and by what we have left undone. We have not loved you with our whole heart; we have not loved our neighbors as ourselves. We are truly sorry and we humbly repent. For the sake of your Son Jesus Christ, have mercy on us and forgive us; that we may delight in your will, and walk in your ways, to the glory of your Name. Amen. Officiant: Almighty God have mercy on you, forgive you all your sins through our Lord Jesus Christ, strengthen you in all goodness, and by the power of the Holy Spirit keep you in eternal life. Amen. The Invitatory and Psalter Officiant: Lord, open our lips. People: And our mouth shall proclaim your praise. All: Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit: as it was in the beginning, is now, and will be for ever. Amen. Officiant: The Lord is full of compassion and mercy: Come let us adore him. Jubilate | Psalm 100 | said together Be joyful in the Lord, all you lands; serve the Lord with gladness and come before his presence with a song. -

Psalms of Praise: “Pesukei Dezimra ”

Dr. Yael Ziegler Pardes The Psalms 1 Psalms of Praise: “Pesukei DeZimra” 1) Shabbat 118b אמר רבי יוסי: יהא חלקי מגומרי הלל בכל יום. איני? והאמר מר: הקורא הלל בכל יום - הרי זה מחרף ומגדף! - כי קאמרינן - בפסוקי דזמרא R. Yosi said: May my portion be with those who complete the Hallel every day. Is that so? Did not the master teach: “Whoever recites the Hallel every day, he is blaspheming and scoffing?” [R. Yosi explained:] When I said it, it was regarding Pesukei DeZimra. Rashi Shabbat 118b הרי זה מחרף ומגדף - שנביאים הראשונים תיקנו לומר בפרקים לשבח והודיה, כדאמרינן בערבי פסחים, )קיז, א(, וזה הקוראה תמיד בלא עתה - אינו אלא כמזמר שיר ומתלוצץ. He is blaspheming and scoffing – Because the first prophets establish to say those chapters as praise and thanks… and he who recites it daily not in its proper time is like one who sings a melody playfully. פסוקי דזמרא - שני מזמורים של הילולים הללו את ה' מן השמים הללו אל בקדשו . Pesukei DeZimra – Two Psalms of Praise: “Praise God from the heavens” [Psalm 148]; “Praise God in His holiness” [Psalm 150.] Massechet Soferim 18:1 Dr. Yael Ziegler Pardes The Psalms 2 אבל צריכין לומר אחר יהי כבוד... וששת המזמורים של כל יום; ואמר ר' יוסי יהא חלקי עם המתפללים בכל יום ששת המזמורים הללו 3) Maharsha Shabbat 118b ה"ז מחרף כו'. משום דהלל נתקן בימים מיוחדים על הנס לפרסם כי הקדוש ברוך הוא הוא בעל היכולת לשנות טבע הבריאה ששינה בימים אלו ...ומשני בפסוקי דזמרה כפירש"י ב' מזמורים של הלולים כו' דאינן באים לפרסם נסיו אלא שהם דברי הלול ושבח דבעי בכל יום כדאמרי' לעולם יסדר אדם שבחו של מקום ואח"כ יתפלל וק"ל: He is blaspheming. -

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim Cantor Sherwood Goffin Faculty, Belz School of Jewish Music, RIETS, Yeshiva University Cantor, Lincoln Square Synagogue, New York City Song has been the paradigm of Jewish Prayer from time immemorial. The Talmud Brochos 26a, states that “Tefillot kneged tmidim tiknum”, that “prayer was established in place of the sacrifices”. The Mishnah Tamid 7:3 relates that most of the sacrifices, with few exceptions, were accompanied by the music and song of the Leviim.11 It is therefore clear that our custom for the past two millennia was that just as the korbanot of Temple times were conducted with song, tefillah was also conducted with song. This is true in our own day as well. Today this song is expressed with the musical nusach only or, as is the prevalent custom, nusach interspersed with inspiring communally-sung niggunim. It once was true that if you wanted to daven in a shul that sang together, you had to go to your local Young Israel, the movement that first instituted congregational melodies c. 1910-15. Most of the Orthodox congregations of those days – until the late 1960s and mid-70s - eschewed the concept of congregational melodies. In the contemporary synagogue of today, however, the experience of the entire congregation singing an inspiring melody together is standard and expected. Are there guidelines for the proper choice and use of “known” niggunim at various places in the tefillot of the Yamim Noraim? Many are aware that there are specific tefillot that must be sung "...b'niggunim hanehugim......b'niggun yodua um'sukon um'kubal b'chol t'futzos ho'oretz...mimei kedem." – "...with the traditional melodies...the melody that is known, correct and accepted 11 In Arachin 11a there is a dispute as to whether song is m’akeiv a korban, and includes 10 biblical sources for song that is required to accompany the korbanos. -

9781845502027 Psalms Fotb

Contents Foreword ......................................................................................................7 Notes ............................................................................................................. 8 Psalm 90: Consumed by God’s Anger ......................................................9 Psalm 91: Healed by God’s Touch ...........................................................13 Psalm 92: Praise the Ltwi ........................................................................17 Psalm 93: The King Returns Victorious .................................................21 Psalm 94: The God Who Avenges ...........................................................23 Psalm 95: A Call to Praise .........................................................................27 Psalm 96: The Ltwi Reigns ......................................................................31 Psalm 97: The Ltwi Alone is King ..........................................................35 Psalm 98: Uninhibited Rejoicing .............................................................39 Psalm 99: The Ltwi Sits Enthroned ........................................................43 Psalm 100: Joy in His Presence ................................................................47 Psalm 101: David’s Godly Resolutions ...................................................49 Psalm 102: The Ltwi Will Rebuild Zion ................................................53 Psalm 103: So Great is His Love. .............................................................57 -

The Mishkan at Central Synagogue Parashat Mas’Ei, July 14, 2018 / 2 Av 5778

The Mishkan at Central Synagogue Parashat Mas’ei, July 14, 2018 / 2 Av 5778 Morning Blessings of Gratitude / Birchot HaShachar Supplementary Prayers and Songs: Gathering / Mah Tovu Waking / Modeh Ani Sanctuary (Text: Exodus 25:8) Music and English Lyrics: R. Scruggs Our Bodies / Asher Yatzar (78) Our Souls / Elohai Neshama Oh, Lord prepare me to be a sanctuary (82) Everyday Miracles / Nisim B’Chol Yom Pure and holy, tried and true; And with thanksgiving Learning Torah I’ll be a living sanctuary for you. Songs of Praise / Pesukei D’Zimrah Psalm 145 / Ashrei Ve'asu li mikdash veshachanti betocham. (96) Psalm 92 / Mizmor Shir l’Yom HaShabbat Va'anachnu nevarech yah me'atah ve'ad (100) Psalm 150 / Hallelujah olam. The Shema and its Blessings (108) Call to Prayer / Bar’chu (Make for me a sanctuary, that I may dwell within you. / And we will praise God now (110) The Wonder of Creation / Yotzeir Or and forever). The Loving Gift of Torah / Ahavah Rabbah (114) Proclaiming God’s Oneness / Shema Mizmor Shir (Text: Psalm 92) (116) V’ahavta Music and English Lyrics: D. Mutlu (122) Song of Our Redemption / Mi Chamocha (122) Our Rock & Redeemer / Tzur Yisrael Mizmor shir l’yom HaShabbat Standing Prayer / Tefillah / Amidah Tov l’hodot l’Adonai Ul’zameir l’shimcha elyon (124) Open our Mouths / Adonai Sefatai Tiftach Mizmor shir l’yom HaShabbat (126) God of Our Ancestors / Avot (128) Life-Giving and Powerful God / G’vurot Good it is to thank You and give praise; Sing a song, to glorify your name. (130) Sanctifying God’s Name / Kedushah Kindness, love, truth and faith; Sanctifying Shabbat / Yis’m’chu or V’Shamru You are by night and day. -

Answers Disguised As Questions: Rhetoric and Reasoning in Psalm 24

Botha: Rhetoric and Reasoning in Psalm 24 OTE 22/3 (2009), 535-553 535 Answers Disguised as Questions: Rhetoric and Reasoning in Psalm 24 PHIL J. BOTHA (U NIVERSITY OF PRETORIA ) ABSTRACT Psalm 24 seems to consist mainly of a hymnic introduction (vv. 1-2), a so-called “entrance torah” (vv. 3-5), and a liturgical piece once used at the temple gates (vv. 7-10), to which a post-exilic identifica- tion of the true Israel was added (v. 6). It contains four questions which are almost universally interpreted as dialectical or antipho- nal questions formulated for the purpose of regulating entrance to the temple within some or other liturgy. This paper consists of a po- etic and rhetorical analysis of the psalm in which it is argued that the questions rather serve a rhetorical function in the present form of Ps 24. The purpose of the questions is to highlight the profile of a true worshipper of YHWH on the one hand, and to highlight the military might and splendour of YHWH on the other. It probably sought to outline the religious profile of the worshipping community in the post-exilic period more clearly, and to reconfirm the consen- sus that they would be vindicated as the true Israel when YHWH would reveal his true power and glory. The psalm is also contextu- alised as part of the post-exilic composition Pss 15-24. A INTRODUCTION It is widely accepted that Ps 24 contains remnants of two liturgical pieces: A so-called “entrance torah” (vv. 3-5, with parallels in Ps 15 and Isa 33), 1 and a so-called “liturgy at the gates” (vv.