Didi-Huberman, the Art of Not Describing Vermeer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Setting up the Palette by Carole Greene

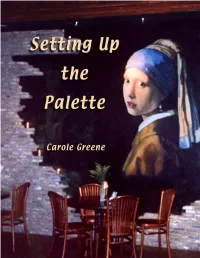

Setting Up the Palette by Carole Greene De Anza College Cupertino, California Manuscript Preparation: D’Artagnan Greene Cover Photo: Hotel Johannes Vermeer Restaurant, Delft, Holland © 2002 by Bill Greene ii Copyright © 2002 by Carole Greene ISBN X-XXXX-XXXX-X All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form whatsoever, by photography or xerography or by any other means, by broadcast or transmission, by translation into any kind of language, nor by recording electronically or otherwise, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in critical articles or reviews. Printed in the United States of America. X X X X X X X X X X Address orders to: XXXXXXXXXXX 1111 XXXX XX XXXXXX, XX 00000-0000 Telephone 000-000-0000 Fax 000-000-0000 XXXXX Publishing XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX iii TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ix CHAPTER 1- Mastering the Tools 1 An Overview 3 The Clause 15 The Simple Sentence 17 The Verb Check 21 Items in a Series 23 Inverted Clauses and Questions 29 Analyzing a Question 33 Exercise 1: Locate Subjects and Verbs in Questions 35 Exercise 2: Locate Verbs in Simple Sentences 37 Exercise 3: Locate Subjects in Simple Sentences 47 Exercise 4: Locate Subjects and Verbs in Simple Sentences 55 iv The Need to Change Reading Habits 69 The Phrase 71 A Phrase Versus a Clause 73 Prepositional Phrases 75 Common Single Word Prepositions 77 Group Prepositions 78 Developing a Memory System 79 Memory Facts 81 Analyzing the Function of Prepositional Phrases 83 Exercise 5: Locating -

General Index

General Index Italicized page numbers indicate figures and tables. Color plates are in- cussed; full listings of authors’ works as cited in this volume may be dicated as “pl.” Color plates 1– 40 are in part 1 and plates 41–80 are found in the bibliographical index. in part 2. Authors are listed only when their ideas or works are dis- Aa, Pieter van der (1659–1733), 1338 of military cartography, 971 934 –39; Genoa, 864 –65; Low Coun- Aa River, pl.61, 1523 of nautical charts, 1069, 1424 tries, 1257 Aachen, 1241 printing’s impact on, 607–8 of Dutch hamlets, 1264 Abate, Agostino, 857–58, 864 –65 role of sources in, 66 –67 ecclesiastical subdivisions in, 1090, 1091 Abbeys. See also Cartularies; Monasteries of Russian maps, 1873 of forests, 50 maps: property, 50–51; water system, 43 standards of, 7 German maps in context of, 1224, 1225 plans: juridical uses of, pl.61, 1523–24, studies of, 505–8, 1258 n.53 map consciousness in, 636, 661–62 1525; Wildmore Fen (in psalter), 43– 44 of surveys, 505–8, 708, 1435–36 maps in: cadastral (See Cadastral maps); Abbreviations, 1897, 1899 of town models, 489 central Italy, 909–15; characteristics of, Abreu, Lisuarte de, 1019 Acequia Imperial de Aragón, 507 874 –75, 880 –82; coloring of, 1499, Abruzzi River, 547, 570 Acerra, 951 1588; East-Central Europe, 1806, 1808; Absolutism, 831, 833, 835–36 Ackerman, James S., 427 n.2 England, 50 –51, 1595, 1599, 1603, See also Sovereigns and monarchs Aconcio, Jacopo (d. 1566), 1611 1615, 1629, 1720; France, 1497–1500, Abstraction Acosta, José de (1539–1600), 1235 1501; humanism linked to, 909–10; in- in bird’s-eye views, 688 Acquaviva, Andrea Matteo (d. -

Interiors and Interiority in Vermeer: Empiricism, Subjectivity, Modernism

ARTICLE Received 20 Feb 2017 | Accepted 11 May 2017 | Published 12 Jul 2017 DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 OPEN Interiors and interiority in Vermeer: empiricism, subjectivity, modernism Benjamin Binstock1 ABSTRACT Johannes Vermeer may well be the foremost painter of interiors and interiority in the history of art, yet we have not necessarily understood his achievement in either domain, or their relation within his complex development. This essay explains how Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and used his family members as models, combining empiricism and subjectivity. Vermeer was exceptionally self-conscious and sophisticated about his artistic task, which we are still laboring to understand and articulate. He eschewed anecdotal narratives and presented his models as models in “studio” settings, in paintings about paintings, or art about art, a form of modernism. In contrast to the prevailing con- ception in scholarship of Dutch Golden Age paintings as providing didactic or moralizing messages for their pre-modern audiences, we glimpse in Vermeer’s paintings an anticipation of our own modern understanding of art. This article is published as part of a collection on interiorities. 1 School of History and Social Sciences, Cooper Union, New York, NY, USA Correspondence: (e-mail: [email protected]) PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | 3:17068 | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 | www.palgrave-journals.com/palcomms 1 ARTICLE PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 ‘All the beautifully furnished rooms, carefully designed within his complex development. This essay explains how interiors, everything so controlled; There wasn’t any room Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and his for any real feelings between any of us’. -

The History of Cartography, Volume 3

THE HISTORY OF CARTOGRAPHY VOLUME THREE Volume Three Editorial Advisors Denis E. Cosgrove Richard Helgerson Catherine Delano-Smith Christian Jacob Felipe Fernández-Armesto Richard L. Kagan Paula Findlen Martin Kemp Patrick Gautier Dalché Chandra Mukerji Anthony Grafton Günter Schilder Stephen Greenblatt Sarah Tyacke Glyndwr Williams The History of Cartography J. B. Harley and David Woodward, Founding Editors 1 Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean 2.1 Cartography in the Traditional Islamic and South Asian Societies 2.2 Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies 2.3 Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies 3 Cartography in the European Renaissance 4 Cartography in the European Enlightenment 5 Cartography in the Nineteenth Century 6 Cartography in the Twentieth Century THE HISTORY OF CARTOGRAPHY VOLUME THREE Cartography in the European Renaissance PART 1 Edited by DAVID WOODWARD THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS • CHICAGO & LONDON David Woodward was the Arthur H. Robinson Professor Emeritus of Geography at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2007 by the University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2007 Printed in the United States of America 1615141312111009080712345 Set ISBN-10: 0-226-90732-5 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90732-1 (cloth) Part 1 ISBN-10: 0-226-90733-3 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90733-8 (cloth) Part 2 ISBN-10: 0-226-90734-1 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90734-5 (cloth) Editorial work on The History of Cartography is supported in part by grants from the Division of Preservation and Access of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Geography and Regional Science Program and Science and Society Program of the National Science Foundation, independent federal agencies. -

Art in the Mirror: Reflection in the Work of Rauschenberg, Richter, Graham and Smithson

ART IN THE MIRROR: REFLECTION IN THE WORK OF RAUSCHENBERG, RICHTER, GRAHAM AND SMITHSON DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Eileen R. Doyle, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Stephen Melville, Advisor Professor Lisa Florman ______________________________ Professor Myroslava Mudrak Advisor History of Art Graduate Program Copyright by Eileen Reilly Doyle 2004 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation considers the proliferation of mirrors and reflective materials in art since the sixties through four case studies. By analyzing the mirrored and reflective work of Robert Rauschenberg, Gerhard Richter, Dan Graham and Robert Smithson within the context of the artists' larger oeuvre and also the theoretical and self-reflective writing that surrounds each artist’s work, the relationship between the wide use of industrially-produced materials and the French theory that dominated artistic discourse for the past thirty years becomes clear. Chapter 2 examines the work of Robert Rauschenberg, noting his early interest in engaging the viewer’s body in his work—a practice that became standard with the rise of Minimalism and after. Additionally, the theoretical writing the French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty provides insight into the link between art as a mirroring practice and a physically engaged viewer. Chapter 3 considers the questions of medium and genre as they arose in the wake of Minimalism, using the mirrors and photo-based paintings of Gerhard Richter as its focus. It also addresses the particular way that Richter weaves the motifs and concerns of traditional painting into a rhetoric of the death of painting which strongly implicates the mirror, ultimately opening up Richter’s career to a psychoanalytic reading drawing its force from Jacques Lacan’s writing on the formation of the subject. -

The Reception of Palaeolithic Art at the Turn of the Twentieth Century: Between Archaeology and Art History

The reception of Palaeolithic art at the turn of the twentieth century: between archaeology and art history Oscar Moro Abadía If I am asked to define any further what I mean by ‘the primitive’ I must refer the reader to the pages of this book, which will show that the term was associated in its time with early Greek vases, with quattrocento painting and with tribal art.1 These words by Ernst Gombrich summarize some of the main meanings associated with the term ‘primitive’ in the field of art history. In its original sense, the word refers to a movement of taste that, in the story of art, runs parallel to the progress towards naturalism. According to Gombrich, while art history may be described as the story of how ‘the artist got better and better in the imitation of nature’,2 there have been a number of artistic movements that have called for a deliberate abandonment of classical standards.3 This ‘preference for the primitive’ has been expressed in ‘the revulsion from that very perfection that art had been said to aim at’.4 During the last years of the nineteenth century, the theory of evolution ‘gave a new meaning to the term ‘primitive’ which […] came to denote the beginnings of human civilization’.5 As a result of this development, the term ‘primitive art’ was incorporated into art historians’ vocabulary to refer to a set of non-Western arts coming from Africa, America and Oceania.6 At the beginning of the twentieth century, ‘primitive art’ was used interchangeably with terms such as ‘savage art’, ‘tribal art’ and ‘art nègre’.7 Since then, the label has been intensively criticized for Acknowledgements. -

Download Download

Global histories a student journal The Construction of Chinese Art History as a Modern Discipline in the Early Twentieth Century Author: Jialu Wang DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/GHSJ.2019.294 Source: Global Histories, Vol. 5, No. 1 (May 2019), pp. 64-77 ISSN: 2366-780X Copyright © 2019 Jialu Wang License URL: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Publisher information: ‘Global Histories: A Student Journal’ is an open-access bi-annual journal founded in 2015 by students of the M.A. program Global History at Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. ‘Global Histories’ is published by an editorial board of Global History students in association with the Freie Universität Berlin. Freie Universität Berlin Global Histories: A Student Journal Friedrich-Meinecke-Institut Koserstraße 20 14195 Berlin Contact information: For more information, please consult our website www.globalhistories.com or contact the editor at: [email protected]. The Construction of Chinese Art History as a Modern Discipline in the Early Twentieth Century by: WANG JIALU Wang Jialu Construction of Chinese Art | 65 | VI - 1 - 2019 Nottingham Ningbo China. ABOUT THE AUTHOR degree in Transcultural Studies at the Studies degree in Transcultural with a particular focus on China and its are Visual, Media and Material Cultures, global art history, and curating practices. global art history, She also holds an MA degree in Identity, She also holds an MA degree in Identity, London and a BA degree in International London contemporary media and cultural studies, Jialu Wang is currently pursuing a Master’s is currently pursuing a Master’s Jialu Wang Culture and Power from University College Culture and Power Communications Studies from University of Communications Studies University of Heidelberg. -

A Review on Historical Earth Pigments Used in India's Wall Paintings

heritage Review A Review on Historical Earth Pigments Used in India’s Wall Paintings Anjali Sharma 1 and Manager Rajdeo Singh 2,* 1 Department of Conservation, National Museum Institute, Janpath, New Delhi 110011, India; [email protected] 2 National Research Laboratory for the Conservation of Cultural Property, Aliganj, Lucknow 226024, India * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Iron-containing earth minerals of various hues were the earliest pigments of the prehistoric artists who dwelled in caves. Being a prominent part of human expression through art, nature- derived pigments have been used in continuum through ages until now. Studies reveal that the primitive artist stored or used his pigments as color cakes made out of skin or reeds. Although records to help understand the technical details of Indian painting in the early periodare scanty, there is a certain amount of material from which some idea may be gained regarding the methods used by the artists to obtain their results. Considering Indian wall paintings, the most widely used earth pigments include red, yellow, and green ochres, making it fairly easy for the modern era scientific conservators and researchers to study them. The present knowledge on material sources given in the literature is limited and deficient as of now, hence the present work attempts to elucidate the range of earth pigments encountered in Indian wall paintings and the scientific studies and characterization by analytical techniques that form the knowledge background on the topic. Studies leadingto well-founded knowledge on pigments can contribute towards the safeguarding of Indian cultural heritage as well as spread awareness among conservators, restorers, and scholars. -

Recent Publications 1984 — 2017 Issues 1 — 100

RECENT PUBLICATIONS 1984 — 2017 ISSUES 1 — 100 Recent Publications is a compendium of books and articles on cartography and cartographic subjects that is included in almost every issue of The Portolan. It was compiled by the dedi- cated work of Eric Wolf from 1984-2007 and Joel Kovarsky from 2007-2017. The worldwide cartographic community thanks them greatly. Recent Publications is a resource for anyone interested in the subject matter. Given the dates of original publication, some of the materi- als cited may or may not be currently available. The information provided in this document starts with Portolan issue number 100 and pro- gresses to issue number 1 (in backwards order of publication, i.e. most recent first). To search for a name or a topic or a specific issue, type Ctrl-F for a Windows based device (Command-F for an Apple based device) which will open a small window. Then type in your search query. For a specific issue, type in the symbol # before the number, and for issues 1— 9, insert a zero before the digit. For a specific year, instead of typing in that year, type in a Portolan issue in that year (a more efficient approach). The next page provides a listing of the Portolan issues and their dates of publication. PORTOLAN ISSUE NUMBERS AND PUBLICATIONS DATES Issue # Publication Date Issue # Publication Date 100 Winter 2017 050 Spring 2001 099 Fall 2017 049 Winter 2000-2001 098 Spring 2017 048 Fall 2000 097 Winter 2016 047 Srping 2000 096 Fall 2016 046 Winter 1999-2000 095 Spring 2016 045 Fall 1999 094 Winter 2015 044 Spring -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Girl with a Flute

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Attributed to Johannes Vermeer Johannes Vermeer Dutch, 1632 - 1675 Girl with a Flute probably 1665/1675 oil on panel painted surface: 20 x 17.8 cm (7 7/8 x 7 in.) framed: 39.7 x 37.5 x 5.1 cm (15 5/8 x 14 3/4 x 2 in.) Widener Collection 1942.9.98 ENTRY In 1906 Abraham Bredius, director of the Mauritshuis in The Hague, traveled to Brussels to examine a collection of drawings owned by the family of Jonkheer Jan de Grez. [1] There he discovered, hanging high on a wall, a small picture that he surmised might be by Vermeer of Delft. Bredius asked for permission to take down the painting, which he exclaimed to be “very beautiful.” He then asked if the painting could be exhibited at the Mauritshuis, which occurred during the summer of 1907. Bredius’ discovery was received with great acclaim. In 1911, after the death of Jonkheer Jan de Grez, the family sold the painting, and it soon entered the distinguished collection of August Janssen in Amsterdam. After this collector’s death in 1918, the painting was acquired by the Amsterdam art dealer Jacques Goudstikker, and then by M. Knoedler & Co., New York, which subsequently sold it to Joseph E. Widener. On March 1, 1923, the Paris art dealer René Gimpel recorded the transaction in his diary, commenting: “It’s truly one of the master’s most beautiful works.” [2] Despite the enthusiastic reception that this painting received after its discovery in the first decade of the twentieth century, the attribution of this work has frequently Girl with a Flute 1 © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century been brought into question by later scholars. -

The R U T G E R S a R T R E V I E W Published Annually by the Students

The RUTGERS ART REVIEW Published Annually by the Students of the Graduate Program in Art History at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey 1991-1992 Volume XII-XI1I Co-Editors, Volume 12: Scott Montgomery Elizabeth Vogel Editorial Board, Volume 12: Marguerite Barrett Arnold Victor Coonin David Foster Cheryl Kramer Stephanie Smith Faculty Advisor, Volume 12: Professor Matthew Baigell Editor, Volume 13: Marguerite Barrett Editorial Board, Volume 13: Shelly Adams Sheilagh Casey Arnold Victor Coonin Pamela Cohen Joanna Gardner Cheryl Kramer Stephanie Smith Faculty Advisor, Volume 13: Archer St Clair Harvey Consulting Editors Volume 12 and 13: Caroline Goeser Priscilla Schwarz Advisory Board, Volume 12 and 13: Patricia Fortini Brown, Princeton University Phillip Dennis Cate, Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Museum Joseph Connors, American Academy in Rome Patricia Leighten, University of Delaware Constance Lowenthal, International Foundation for Art Research David G. Wilkins, University of Pittsburgh Benefactors ($1,000 or more) The Graduate School, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey The Graduate Student Association, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey The Johnson and Johnson Family of Companies Contributors ($100 or more) Rona Goffen Supporters ($50 or more) Shelly Adams and Edgar Morales Matthew and Ren6e Baigell Catherine Puglisi and William Barcham Daniel and Patricia Sheerin Friends ($25 or more) Charles L. Barrett III M. B. Barrett Alice A. Bauer Arnold Victor Coonin Marianne Ficarra Donald Garza Marion Husid Tod Marder Joan Matter Brooke Kamin Rapaport Claire Renkin Stephen A. Somers, with an Employer Match Donation from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Jack Spector David and Ann Wilkins The following persons generously donated funds to Volume 11 of the Rutgers Art Review.