The R U T G E R S a R T R E V I E W Published Annually by the Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

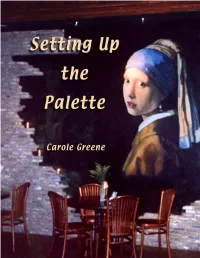

Setting up the Palette by Carole Greene

Setting Up the Palette by Carole Greene De Anza College Cupertino, California Manuscript Preparation: D’Artagnan Greene Cover Photo: Hotel Johannes Vermeer Restaurant, Delft, Holland © 2002 by Bill Greene ii Copyright © 2002 by Carole Greene ISBN X-XXXX-XXXX-X All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form whatsoever, by photography or xerography or by any other means, by broadcast or transmission, by translation into any kind of language, nor by recording electronically or otherwise, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in critical articles or reviews. Printed in the United States of America. X X X X X X X X X X Address orders to: XXXXXXXXXXX 1111 XXXX XX XXXXXX, XX 00000-0000 Telephone 000-000-0000 Fax 000-000-0000 XXXXX Publishing XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX iii TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ix CHAPTER 1- Mastering the Tools 1 An Overview 3 The Clause 15 The Simple Sentence 17 The Verb Check 21 Items in a Series 23 Inverted Clauses and Questions 29 Analyzing a Question 33 Exercise 1: Locate Subjects and Verbs in Questions 35 Exercise 2: Locate Verbs in Simple Sentences 37 Exercise 3: Locate Subjects in Simple Sentences 47 Exercise 4: Locate Subjects and Verbs in Simple Sentences 55 iv The Need to Change Reading Habits 69 The Phrase 71 A Phrase Versus a Clause 73 Prepositional Phrases 75 Common Single Word Prepositions 77 Group Prepositions 78 Developing a Memory System 79 Memory Facts 81 Analyzing the Function of Prepositional Phrases 83 Exercise 5: Locating -

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art by Adam Mccauley

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art Adam McCauley, Studio Art- Painting Pope Wright, MS, Department of Fine Arts ABSTRACT Through my research I wanted to find out the ideas and meanings that the originators of non- objective art had. In my research I also wanted to find out what were the artists’ meanings be it symbolic or geometric, ideas behind composition, and the reasons for such a dramatic break from the academic tradition in painting and the arts. Throughout the research I also looked into the resulting conflicts that this style of art had with critics, academia, and ultimately governments. Ultimately I wanted to understand if this style of art could be continued in the Post-Modern era and if it could continue its vitality in the arts today as it did in the past. Introduction Modern art has been characterized by upheavals, break-ups, rejection, acceptance, and innovations. During the 20th century the development and innovations of art could be compared to that of science. Science made huge leaps and bounds; so did art. The innovations in travel and flight, the finding of new cures for disease, and splitting the atom all affected the artists and their work. Innovative artists and their ideas spurred revolutionary art and followers. In Paris, Pablo Picasso had fragmented form with the Cubists. In Italy, there was Giacomo Balla and his Futurist movement. In Germany, Wassily Kandinsky was working with the group the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), and in Russia Kazimer Malevich was working in a style that he called Suprematism. -

Hagerman National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Hagerman National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan April2006 United States Department of the Interior FISH AND Wll...DLIFE SERVICE P.O. Box 1306 Albuquerque, New Mexico 87103 In Reply Refer To: R2/NWRS-PLN JUN 0 5 2006 Dear Reader: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is proud to present to you the enclosed Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP) for the Hagerman National Wildlife Refuge (Refuge). This CCP and its supporting documents outline a vision for the future of the Refuge and specifies how this unique area can be maintained to conserve indigenous wildlife and their habitats for the enjoyment of the public for generations to come. Active community participation is vitally important to manage the Refuge successfully. By reviewing this CCP and visiting the Refuge, you will have opportunities to learn more about its purpose and prospects. We invite you to become involved in its future. The Service would like to thank all the people who participated in the planning and public involvement process. Comments you submitted helped us prepare a better CCP for the future of this unique place. Sincerely, Tom Baca Chief, Division of Planning Hagerman National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan Sherman, Texas Prepared by: United States Fish and Wildlife Service Division of Planning Region 2 500 Gold SW Albuquerque, New Mexico 87103 Comprehensive conservation plans provide long-term guidance for management decisions and set forth goals, objectives, and strategies needed to accomplish refuge purposes and identify the Service’s best estimate of future needs. These plans detail program planning levels that are sometimes substantially above current budget allocations and, as such, are primarily for Service strategic planning and program prioritization purposes. -

Interiors and Interiority in Vermeer: Empiricism, Subjectivity, Modernism

ARTICLE Received 20 Feb 2017 | Accepted 11 May 2017 | Published 12 Jul 2017 DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 OPEN Interiors and interiority in Vermeer: empiricism, subjectivity, modernism Benjamin Binstock1 ABSTRACT Johannes Vermeer may well be the foremost painter of interiors and interiority in the history of art, yet we have not necessarily understood his achievement in either domain, or their relation within his complex development. This essay explains how Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and used his family members as models, combining empiricism and subjectivity. Vermeer was exceptionally self-conscious and sophisticated about his artistic task, which we are still laboring to understand and articulate. He eschewed anecdotal narratives and presented his models as models in “studio” settings, in paintings about paintings, or art about art, a form of modernism. In contrast to the prevailing con- ception in scholarship of Dutch Golden Age paintings as providing didactic or moralizing messages for their pre-modern audiences, we glimpse in Vermeer’s paintings an anticipation of our own modern understanding of art. This article is published as part of a collection on interiorities. 1 School of History and Social Sciences, Cooper Union, New York, NY, USA Correspondence: (e-mail: [email protected]) PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | 3:17068 | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 | www.palgrave-journals.com/palcomms 1 ARTICLE PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 ‘All the beautifully furnished rooms, carefully designed within his complex development. This essay explains how interiors, everything so controlled; There wasn’t any room Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and his for any real feelings between any of us’. -

Berta Fischer, Björn Dahlem, Naum Gabo Into Space

PRESS RELEASE Exhibtion Berta Fischer, Björn Dahlem, Naum Gabo Into Space Haus am Waldsee International Art in Berlin 18 October 2020 to 10 January 2021 Press preview: Fri, 16 October 2020, 11 am. Berta Fischer and Björn Dahlem will be present. „Into Space“ deals with the human longing for space, weightlessness, distant galaxies and the belief in hitherto incomprehensible energies beyond our perception. Three sculp- tors reflect upon the interfaces between art and science over a century and from Berlin. Following the exhibition „Lynn Chadwick, Hans Uhlmann, Katja Strunz“, which explored the subject of „Fold“ at Haus am Waldsee in 2019, Björn Dahlem (*1974), Berta Fischer (*1973) and Naum Gabo (1890 - 1977) are now taking up an artistic conversation about space and time between 1920 and 2020 with installations and sculptures. For Naum Gabo, art in the 1920s was a means of gaining knowledge about the physics of our planet. The Jewish-Russian artist, who had emigrated to Berlin, had shortly before written the „Realistic Manifesto“ with his brother Antoine Pevsner, which was ground-breaking for sculpture. He was constantly searching for new materials and means of expression, „not for the sake of the new, but to find expression for the new view of the world around me and for new insights into the forces of life and nature within me”. Even before the First World War, the latest disco- veries in natural science, Albert Einstein‘s theory of relativity and the idea of the fourth dimen- sion as hyperspaces had already profoundly shaken the previous understanding of the laws of nature, which Gabo experienced directly during his studies of medicine and natural sciences in Munich from 1910 onwards. -

Recent Publications 1984 — 2017 Issues 1 — 100

RECENT PUBLICATIONS 1984 — 2017 ISSUES 1 — 100 Recent Publications is a compendium of books and articles on cartography and cartographic subjects that is included in almost every issue of The Portolan. It was compiled by the dedi- cated work of Eric Wolf from 1984-2007 and Joel Kovarsky from 2007-2017. The worldwide cartographic community thanks them greatly. Recent Publications is a resource for anyone interested in the subject matter. Given the dates of original publication, some of the materi- als cited may or may not be currently available. The information provided in this document starts with Portolan issue number 100 and pro- gresses to issue number 1 (in backwards order of publication, i.e. most recent first). To search for a name or a topic or a specific issue, type Ctrl-F for a Windows based device (Command-F for an Apple based device) which will open a small window. Then type in your search query. For a specific issue, type in the symbol # before the number, and for issues 1— 9, insert a zero before the digit. For a specific year, instead of typing in that year, type in a Portolan issue in that year (a more efficient approach). The next page provides a listing of the Portolan issues and their dates of publication. PORTOLAN ISSUE NUMBERS AND PUBLICATIONS DATES Issue # Publication Date Issue # Publication Date 100 Winter 2017 050 Spring 2001 099 Fall 2017 049 Winter 2000-2001 098 Spring 2017 048 Fall 2000 097 Winter 2016 047 Srping 2000 096 Fall 2016 046 Winter 1999-2000 095 Spring 2016 045 Fall 1999 094 Winter 2015 044 Spring -

Deborah Moggach, Zbigniew Herbert and Dutch Painting of the Seventeenth Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Jagiellonian Univeristy Repository Studia Litteraria Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis 10 (2015), z. 2, s. 131–151 doi: 10.4467/20843933ST.15.012.4103 www.ejournals.eu/Studia-Litteraria MAREK KUCHARSKI Uniwersytet Jagielloński w Krakowie e-mail: [email protected] Intertextual and Intermedial Relationships: Deborah Moggach, Zbigniew Herbert and Dutch Painting of the Seventeenth Century Abstract The aim of the article is to analyse the intertextual and intermedial relationships between Tulip Fever, a novel by Deborah Moggach, The Bitter Smell of Tulips, an essay by Zbigniew Herbert from the collection Still Life with a Bridle, with some selected examples of Dutch paintings of the seventeenth century. As Moggach does not confi ne herself only to the aforementioned essay by Herbert, I will also refer to other essays from the volume as well as to the essay Mistrz z Delft which comes from the collection of the same title. Keywords: Deborah Moggach, Zbigniew Herbert, novel, essay, Dutch paintings, intertextuality, intermediality. Zbigniew Herbert’s essay The Bitter Smell of Tulips comes from the collection Still Life with a Bridle which is a part of the trilogy that, apart from the afore- mentioned collection of essays, consists of two other volumes: Labyrinth on the Sea and Barbarian in the Garden. In each of the volumes, in the form of a very personal account of his travels, Herbert spins a yarn of European culture and civi- lization. Labyrinth on the Sea focuses on the history and culture of ancient Greece and Rome whereas in Barbarian in the Garden Herbert draws on the whole spec- trum of subjects ranging from the prehistoric paintings on the walls of the cave in Lascaux, through the Gothic cathedrals and Renaissance masterpieces, to the stories about the Albigensians and the persecution of the Knights of the Templar Order. -

Naum Gabo Rediscovered: Revelations on a Constructivist Pioneer” with Stephen Nash, 1986

Guggenheim Museum Archives Reel-to-Reel collection “Naum Gabo Rediscovered: Revelations on a Constructivist Pioneer” with Stephen Nash, 1986 PART 1 SUSAN HIRSCHFELD [00:11] Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. My name is Susan Hirschfeld. I’m assistant curator at the Guggenheim, and I’m delighted to welcome you all here this evening to the second of two lectures being given in conjunction with the Naum Gabo exhibition. I am particularly pleased to introduce tonight’s speaker, Dr. Stephen Nash, who organized the Gabo retrospective and wrote the main catalogue essay. Dr. Nash received his PhD from Stanford University, and wrote his dissertation on the drawings of Jacques-Louis David. Dr. Nash subsequently served on the art history faculties of the University of Delaware and the State University of New York at Buffalo. He served on the staff of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery [00:01:00] in Buffalo from 1973 to 1980 as research curator, chief curator, and then assistant director. In addition to the many lectures and symposia papers he has delivered, Dr. Nash has also written extensively for art journals and publications on such subjects as David, Rodchenko, [Carilli?], and Bonnard. While at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Dr. Nash organized exhibitions on Ben Nicholson, modern European sculpture from 1918 to 1945, and also on constructivism and the geometric tradition in the collection of the McCrory Collection. Since becoming chief curator and deputy director of the Dallas Museum of Art in 1980, Dr. Nash has prepared numerous exhibitions, including a show of Picasso’s graphics, and he was co- organizer of the 1984 exhibition of Pierre Bonnard’s [02:00] Late Paintings. -

Girl with a Flute

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Attributed to Johannes Vermeer Johannes Vermeer Dutch, 1632 - 1675 Girl with a Flute probably 1665/1675 oil on panel painted surface: 20 x 17.8 cm (7 7/8 x 7 in.) framed: 39.7 x 37.5 x 5.1 cm (15 5/8 x 14 3/4 x 2 in.) Widener Collection 1942.9.98 ENTRY In 1906 Abraham Bredius, director of the Mauritshuis in The Hague, traveled to Brussels to examine a collection of drawings owned by the family of Jonkheer Jan de Grez. [1] There he discovered, hanging high on a wall, a small picture that he surmised might be by Vermeer of Delft. Bredius asked for permission to take down the painting, which he exclaimed to be “very beautiful.” He then asked if the painting could be exhibited at the Mauritshuis, which occurred during the summer of 1907. Bredius’ discovery was received with great acclaim. In 1911, after the death of Jonkheer Jan de Grez, the family sold the painting, and it soon entered the distinguished collection of August Janssen in Amsterdam. After this collector’s death in 1918, the painting was acquired by the Amsterdam art dealer Jacques Goudstikker, and then by M. Knoedler & Co., New York, which subsequently sold it to Joseph E. Widener. On March 1, 1923, the Paris art dealer René Gimpel recorded the transaction in his diary, commenting: “It’s truly one of the master’s most beautiful works.” [2] Despite the enthusiastic reception that this painting received after its discovery in the first decade of the twentieth century, the attribution of this work has frequently Girl with a Flute 1 © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century been brought into question by later scholars. -

Brandenburg 23 Johannes Vermeer.Pdf

The Brandenburg 300 Project Honors Home Page Album Notes Monterey Jazz Festival Monarch Butterfly Brandenburg #1 11: Franklin 12-3 Perricone 14: Hicks 15: Penkovsky 16 Earle 17-8 Morales Brandenburg #2 21: Martin Luther King 21: Guadalupe 21: Voyager Brandenbone 21 22: Rembrandt Van Rijn 22: Joe Manning 23: Leonardo DaVinci 23: Johannes Vermeer 23: Pythagoras Brandenburg #3 31: John Schoenoff Brandello 31 Monterey 323: Woody Woodland Brandenburg #4 41: Helen Iwanaga 42: Lloyd Pementil 43: Marie Curie 43: Albert Einstein 43: Linus Pauling Brandenburg #5 52-1: Lafayette 53: Shen Zhou Brandenburg #6 62-1: Voyager 2 63: San BirdBach Badinerie Magic Steps Brandenburg Medley Monterey Masters and the Ashokan Farewell Links and Info Home Page Album Notes Monterey Jazz Festival Monarch Butterfly Brandenburg #1 11: Franklin 12-3 Perricone 14: Hicks 15: Penkovsky 16 Earle 17-8 Morales Brandenburg #2 21: Martin Luther King 21: Guadalupe 21: Voyager Brandenbone 21 22: Rembrandt Van Rijn 22: Joe Manning 23: Leonardo DaVinci 23: Johannes Vermeer 23: Pythagoras Brandenburg #3 31: John Schoenoff Brandello 31 Monterey 323: Woody Woodland Brandenburg #4 41: Helen Iwanaga 42: Lloyd Pementil 43: Marie Curie 43: Albert Einstein 43: Linus Pauling Brandenburg #5 52-1: Lafayette 53: Shen Zhou Brandenburg #6 62-1: Voyager 2 63: San BirdBach Badinerie Magic Steps Brandenburg Medley Monterey Masters and the Ashokan Farewell Links and Info Johannes Vermeer was a Dutch painter who produced a small number of paintings, but those few are timeless masterpieces. Many of his paintings have musical themes. He died 10 years after Bach was born – the same year Bach became an orphan. -

Collana Del Dipartimento Di Studi Storici Università Di Torino 9

COLLANA DEL DIPARTIMENTO DI STUDI STORICI UNIVERSITÀ DI TORINO 9 Jennifer Cooke Millard Meiss Tra connoisseurship, iconologia e Kulturgeschichte Ledizioni © 2015 Ledizioni LediPublishing Via Alamanni, 11 – 20141 Milano – Italy www.ledizioni.it [email protected] Jennifer Cooke, Millard Meiss. Tra connoisseurship, iconologia e Kulturgeschichte Prima edizione: settembre 2015 ISBN Cartaceo: 978-88-6705-370-4 ISBN ePub: 978-88-6705-371-1 Copertina e progetto grafico: ufficio grafico Ledizioni COLLANA DEL DIPARTIMENTO DI STUDI STORICI DELL’UNIVERSITÀ DI TORINO DIRETTORE DELLA COLLANA: Adele Monaci COMITATO SCIENTIFICo: Secondo Carpanetto, Giovanni Filoramo, Carlo Lippolis, Stefano Musso, Sergio Roda, Gelsomina Spione, Maria Luisa Sturani, Marino Zabbia Nella stessa collana sono stati pubblicati in versione cartacea ed ePub: 1. DAVIDE LASAGNO, Oltre l’Istituzione. Crisi e riforma dell’assistenza psichiatrica a Torino e in Italia 2. LUCIANO VILLANI, Le borgate del fascismo. Storia urbana, politica e sociale della periferia romana 3. ALESSANDRO ROSSI, Muscae moriturae donatistae circumvolant: la costruzione di identità “plurali” nel cristianesimo dell’Africa Romana 4. DANIELE PIPITONE, Il socialismo democratico italiano fra la Liberazione e la legge truffa. Fratture, ricomposizioni e culture politiche di un’area di frontiera. 5. MARIA D’AMURI, La casa per tutti nell’Italia giolittiana. Provvedimenti e iniziative per la municipalizzazione dell’edilizia popolare 6. EMILIANO RUBENS URCIUOLI, Un’archeologia del “noi” cristiano. Le «comunità immaginate» -

![Naum Gabo [And] Antoine Pevsner Introduction by Herbert Read, Text by Ruth Olson and Abraham Chanin](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4306/naum-gabo-and-antoine-pevsner-introduction-by-herbert-read-text-by-ruth-olson-and-abraham-chanin-1574306.webp)

Naum Gabo [And] Antoine Pevsner Introduction by Herbert Read, Text by Ruth Olson and Abraham Chanin

Naum Gabo [and] Antoine Pevsner Introduction by Herbert Read, text by Ruth Olson and Abraham Chanin Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1948 Publisher [publisher not identified] Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3228 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art . n a u m I G A B O Introduction by Herbert Head Text by The Museum of Modern Ruth Olson and Abraham Chanin Art , New York City Introduction by Herbert Head Text by t he Museum of Modern Ruth Olson and Abraham Chanin Copyright, 1948, The Museum of Modern Art. Printed in the United States of America. tit? A j> & °i Contents page fy. Acknowledgment 6: Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art 7: Constructivism: The Art of Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner by Herbert Read 14: ISau m Gabo by Ruth Olson and Abraham Chanin 47 : Catalog of the Gabo exhibition 48: Gabo bibliography by Hannah B. Muller 50: Antoine Pevsner by Ruth Olson and Abraham Chanin 82: Catalog of the Pevsner exhibition 83: Pevsner bibliography by Hannah B. Muller 4 Acknowledgmen t On behalf of the Trustees of the Museum of Modern Art , I wish to extend grateful acknowledgment to Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner for their unsparing cooperation; to Wallace K. Harrison , Societe Anonyme at Yale University and to Washington University, St. Louis, for lending works in the exhibitions ; to Alfred H.